Home › Forum › Political Economy › ההון ושברו (Capital and its Crisis) › Reply To: ההון ושברו (Capital and its Crisis)

In a world where the capitalist uses the capitalization equation to set what it will pay for input costs such as wages by discounting its expected profits from future sales, the discount rate used by the capitalist determines (and ensures) the capitalist’s profits. See equation 6, below.

Scot, That’s a clever way of presenting your point, but I don’t think the point itself is correct. 1. What capitalists agree to pay workers certainly depends on their profit expectations, but this dependency is not what your equations express.

Jonathan,

Thanks for the comments, which are very helpful. Let me see if I can clarify things, in part by making some things explicit that may not have been.

My equation 6 is ex ante, just like the capitalization equation at page 154 of Capital as Power (2009), and flows from my past experience in setting annual budgets for firms. So, just as capitalists agree to pay for a share of a firm’s stock based on expectations of future earnings, firms budget for input costs (e.g., wages) based on expectations of future profits. I explicitly argue this in my original comment deriving equation 6:

Equation 6 is the same form as the capitalization formula (5) found at the bottom of page 154 of Capital as Power (2009). Thus, wages paid to labor today can be viewed properly as the “risk-adjusted discounted value of expected future earnings” (i.e., Profitst+1), i.e., wages can be viewed as the capitalization of expected profits (or power, if you would prefer). As you’ve said, “capitalization represents the present value of a future stream of earnings: it tells us how much a capitalist would be prepared to pay now to receive a flow of money later.” Capital as Power, at p. 153.

While I agree that firms don’t explicitly employ the discounting formula or a discount rate as part of their annual budgeting process, inherently (mathematically) they do, if they use target mark-ups or profit margins (most capitalist firms use both in some way). That’s what my derivation of equation 6 was intended to show.

2. The discount rate is what investors use to capitalize expected future profits. In your equations, though, r is not the discount rate (the rate of growth of capitalization), but the profit markup over costs (assuming all costs can be expressed as wages).

Actually, the discount rate is a feature of discounting wherever and however applied. There is no single discount rate for everything at every level of the capitalist system, but every instance of discounting has a corresponding discount rate. Thus, the discount rate of a loan extended to a firm can be different than the discount rate the firm applies to expected profits to budget costs (including wages), which in turn can be different than the discount rate capitalists apply to the firm’s expected future earnings. If discounting is used to price money, wages, and equities, the capitalist system is basically a fractal as each level of the system (money, labor, equities) is “self-similar” to the other because each uses discounting to set prices to accumulate power.

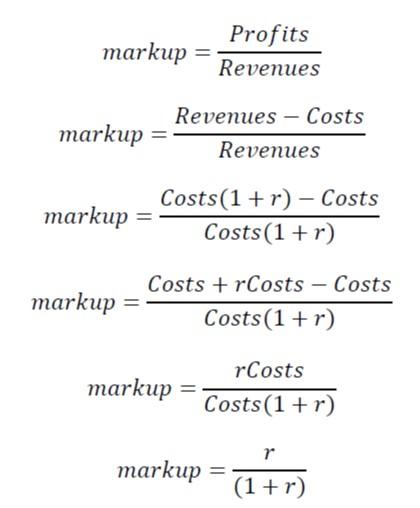

Also, the formula for markup is r/(1+r), not 1/r:

3. Moreover, the way you express it, r reflects not the intended markup, but the realized one.

Actually, my intention was to express expected profits, not realized profits, and I said so in my original comment deriving equation 6, as shown above. If we say “expected” instead of “intended,” the same is true of the way you express r in equation 5 at the bottom of page 154 of Capital as Power (2009). Does the future often prove that such expectations were unwarranted? Sure, but that doesn’t make using discounting any less useful for planning/pricing.

The point of discounting is to commensurate two values of the same thing separated in time. The only value we actually ever know is the the present value. The future value is always speculative, which is okay because firms can reduce spending (the present value ) if it appears the future value will fall short of expectations, and they can do so in a manner that adjusts the effective discount rate to make up for missing prior expectations.

Again, budgeting does not explicitly apply discounting, but if the budget includes expectations of profits, it inherently uses discounting.

4. The realized markup – and therefore actual future profit — is neither at the capitalist’s discretion nor knowable beforehand. It depends on how much capitalists will be able to sell in the future, which is anybody’s guess (and the reason why profit forecasters are almost always wrong).

Again, this is true of the capitalization equation at page 154 of Capital as Power (2009). A key difference between capitalization and annual budgeting is that firms plan one fiscal year at a time. It is much easier for firms to forecast revenues/profits accurately on an annual basis than it is for capitalists to price equities into infinity. Also, a firm has the ability to control its expenses, while investors in the firm do not have the ability to control the firm’s earnings.

I recognize that your capitalization equation is somewhat simplified and idealized, but, however expressed, the market capitalization of a firm as calculated by using the last sale price of shares is never accepted by capitalists as an accurate statement of the firm’s value. If that were the case, no shares would transact (every sale of stock is the seller shorting the stock and the buyer going long). This is why financial analysts use things like discounted cash flow analysis to assess what they believe is the actual “intrinsic” share price of a firm.

5. Since capitalists don’t know their actual future profit, they cannot set current wages as a function of that profit.

Nobody knows the future, which is why everybody sets prices (or budgets expenses, or sets a share price objective) based on expectations. Banks make loans knowing there is a risk of default. Firms set annual budgets based on expected profits knowing there is a risk they will not be able to meet expectations. Financial analysts set price objectives using current expectations of future earnings knowing the firm may not meet future expectations.

Anyway, firms set budgets to constrain expenses, including payrolls. If profit targets seem unlikely to be met, the firm can reduce its workforce through layoffs to achieve the desired discount rate (or markup, which is determined by the discount rate).

6. By definition, the wage bill is the product of the wage rate and the level of employment. In general, capitalists control the level of employment — but, in my view, they don’t set the wage rate, which is the result of historical conditions and an ongoing, complex power conflict within the firm and across society. Expected (though not actual) future profit is merely one element of this conflict.

Okay, but each firm determines how large its payroll is. Make of it what you will.

7. For Kalecki, the markup reflects capitalist power. But this reflection is ex post, not ex ante. The discount rate, by contrast, is set ex ante, not ex post. I think it is erroneous to treat them as if they were the same.

During the annual budgeting process, the discount rate and the markup are both set ex ante. That’s just the nature of the budgeting process, the relationship between profits and costs, and the math of discounting. Given an expected markup of m, you can determine the expected discount rate r, even if the concept of “discount rate” and the discounting formula are never explicitly used in the budgeting process.

8. Perhaps it will be useful to try to express your equations in ex-ante terms (rather than ex post), using the discount rate (rather than the markup).

The discounting formula is always ex ante because the future value at time t+1 is not known but expected. Since my equation 6 distinguishes between time t (the present) and time t+1 (the future), I think the suggested work has already been done.

Am I still missing something? The best critique I can see of what I’ve tried to do is that CasP’s capitalization equation is based on a number of simplifying assumptions that I don’t have to make, and the actual math of applying discounted cash flow analysis to determine the intrinsic value of a firm is much more complicated and messy than we are discussing. That’s okay to me because it is enough to be “self-similar,” if the iterative use of discounting over time and space results in capitalism being fractal in nature (which I think it does). Capitalism’s “mega-machine” may just be a self-replicating “nano-bot” called discounting.

Before I finish, we should circle back to the concept that discounting commensurates (equilibrates, really) two values or prices, separated in time, both for the same object. I think this is really important, but I have not had the chance to think through the implications except for how it implies the logic of capitalism is fractal, which may explain why it seems to be so totalizing.