What if the Government is Just Another Firm? (Part 1)

September 17, 2020

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down.

I have a confession. I’m a political economist by trade, but I spend most of my time reading outside my discipline. I read about physics, cosmology, biology … the list goes on. Basically, if it’s not political economy, I read it.

Usually this reading doesn’t relate to my own research. I do it because I love science. But every so often lightning strikes and I discover a scientific idea that begs to be applied to political economy. This post is about one of those ideas.

Let me frame the problem.

Modern societies have two basic types of institutions: governments and firms. On the surface, these two institutions appear to be unrelated. Here’s a partial list of differences. Governments earn income by taxing citizens. Firms earn income by charging customers. Governments enforce laws. Firms obey laws. Governments can wage war. Firms cannot. Governments can create money. Firms (for the most part) cannot. I could keep listing differences, but you get the point. Governments are different than firms.

Political economists love to emphasize differences like this — as do many social scientists. But I’ve come to believe that searching for differences isn’t a good way to do science. Let’s use biology as an example. Searching for differences is what biologists did before Darwin. Biologists documented the diverse traits of different organisms. And they celebrated this sea of differences. The problem was that this sea didn’t lead anywhere. Differences (on their own) were a scientific dead end.

Here’s how Darwin fixed the problem. Rather than emphasize differences, Darwin emphasized the shared features of different organisms. Suddenly the pieces fit together. Yes, organisms are different, but their shared features point to something astonishing. All life on Earth, it seems, shares a common evolutionary heritage. By mapping the similarities between species, we can reconstruct the evolutionary tree of life.

This idea revolutionized biology. After Darwin, biologists searched voraciously for regularities amongst life. And they didn’t come up dry. Biologists discovered the shared structure of cells. They discovered DNA. And they discovered the biomass spectrum.

What’s the biomass spectrum? It’s a relation between the size of an organism and its abundance. It’s based on a trend that you know intuitively. Small organisms (like mice) are abundant. Large organisms (like elephants) are rare. The astonishing thing, though, is that this trend extends across the entire spectrum of life. From bacteria to blue whales, the abundance of an organism is predictable from its size alone.

Lightning strike.

While studying the biomass spectrum, I was reminded of business firms. Similar to organisms, the abundance of firms declines with size. Small firms are abundant. Large firms are rare. I’ve studied this phenomenon for years. But until recently, I’d never asked an important question: where do governments fit into the picture?

With the biomass spectrum in mind, it occurred to me that governments might be like whales.

Let me explain.

Whales are the largest living animals. As such, they’re exquisitely different from other animals. Yet when it comes to predicting whales’ abundance, these differences are irrelevant. Whales are ‘just another organism’. Their abundance is predictable from size alone.

Might the same principle be true of governments? Yes, governments are exquisitely different than business firms. But what if, despite this difference, the abundance of government is predictable from its size alone? In other words, what if government is ‘just another firm’?

This idea sounds crazy. But in this two-part post, I’m going to show you that it’s consistent with the evidence.

The biomass spectrum

For the moment, let’s leave behind the myopia of our human world. Let’s gaze at life in all its splendour. Life comes in all shapes and sizes. But have you ever thought about the scale of this variation? It’s stupendous.

In terms of mass, a single-celled prokaryote (the smallest organism) is about 20 orders of magnitude smaller than a blue whale (the largest animal). Let’s put this in perspective. If the prokaryote was a 1 ton boulder, the blue whale would weigh as much as the Earth.

Amidst this stupendous variation, it almost defies imagination that there could be underlying order. And yet there is. To predict an organism’s abundance, we don’t need to know its species, its diet, or its habitat. No, to predict abundance, we need only know the organism’s mass. Biologists call this pattern the biomass spectrum.

Until recently, biologists studied this spectrum in piecemeal. They looked at the biomass spectrum in specific ecosystems. Or they looked at the biomass spectrum within a specific animal taxa. But no one had looked at the whole picture.

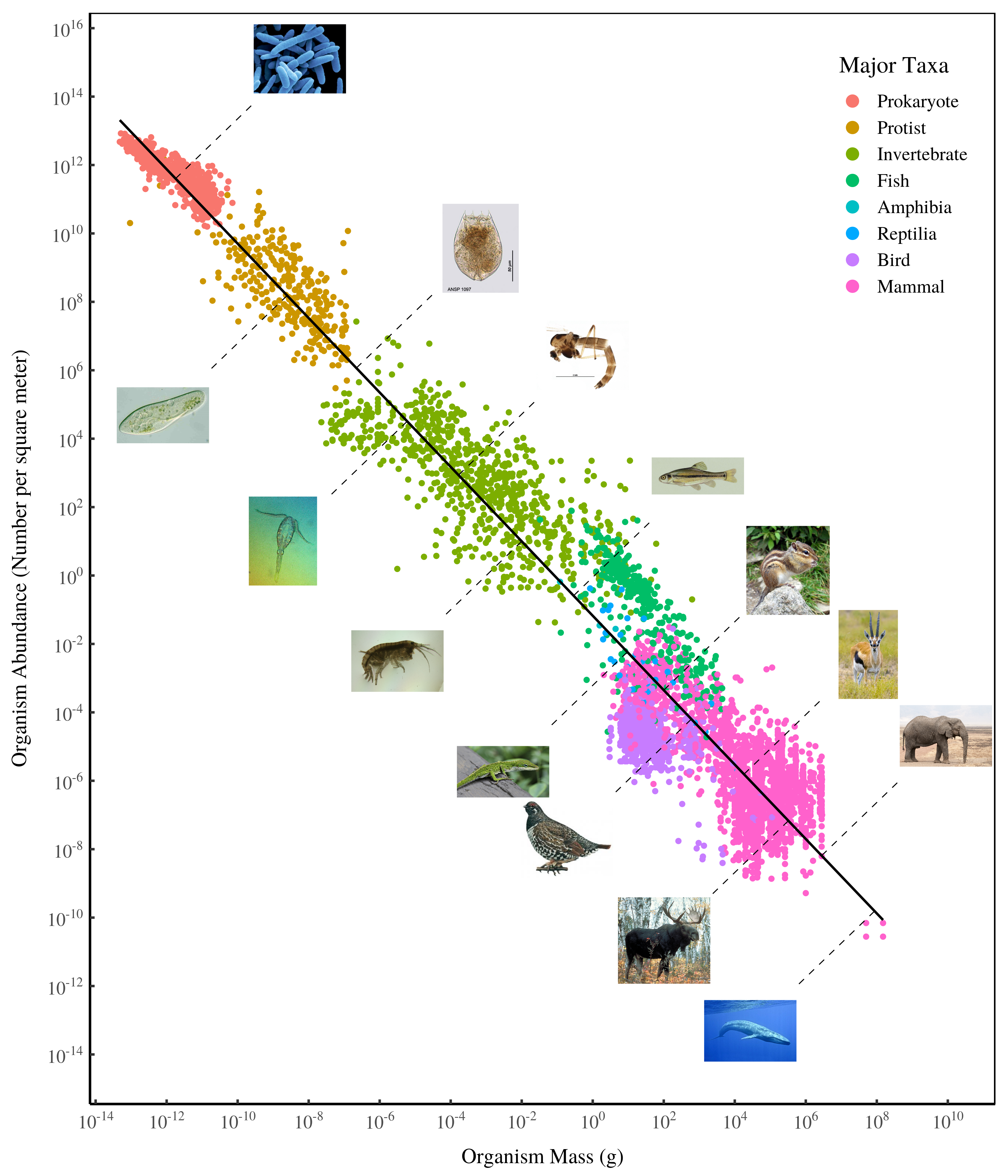

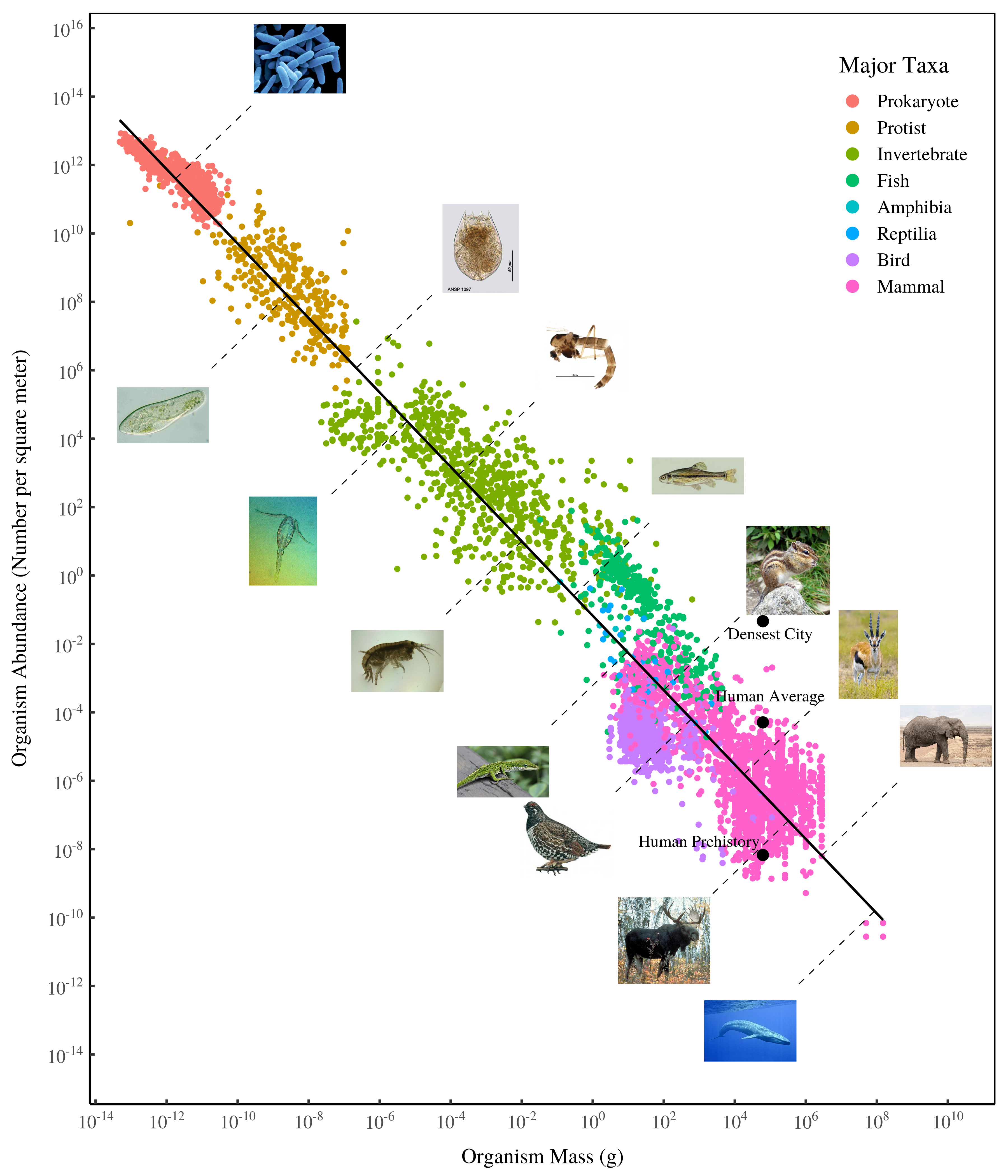

Enter Ian Hatton and colleagues. In a recent paper, Hatton and his collaborators studied the biomass spectrum across all organisms. What they found is astonishing. From the smallest prokaryote to the largest mammal, organism abundance declines predictably with size. Figure 1 shows the trend.

Figure 1: The biomass spectrum. Each dot represents an observation for a species. Color indicates the major taxa. Data is from Hatton et al., Linking scaling laws across eukaryotes. I’ve left out plants, which lie slightly off the trend for the other taxa. I’ve also added my own estimates for the abundance of humans and blue whales [1].

There are two things that are interesting about the biomass spectrum. First, there is a single trend between mass and abundance that runs though all life on Earth. (Well, almost all life. I’ve excluded plants here, because they lie somewhat off the trend.) Second, different types of organisms have distinct locations on the trend. Prokaryotes are small and ubiquitous. Invertebrates are medium sized and common. Mammals are large and rare.

Looking at this biomass trend, it struck me that something similar might be true of human institutions. Independent restaurants, for instance, are small and ubiquitous. But mining firms are large and rare. If we keep going up the size spectrum, I propose that we’ll get to an entirely different institution: government. Governments are the whales of the institution world. They’re exquisitely different from other institutions. But like the abundance of whales, I propose that the abundance of government is predictable from size alone.

A model of government abundance

With the biomass spectrum in mind, I’m going to propose a simple model of government abundance. I call it the ‘government-as-firm’ model. Here’s how it works.

Similar to how organism abundance declines with mass, we assume that the abundance of human institutions (regardless of type) declines with size. Small institutions are abundant. Large institutions are rare.

Next, we imagine that governments are the whales of the institutional world. Just as whales are the largest animals, governments are the largest institutions. And like whales, we suppose that the abundance of government is predictable from size alone.

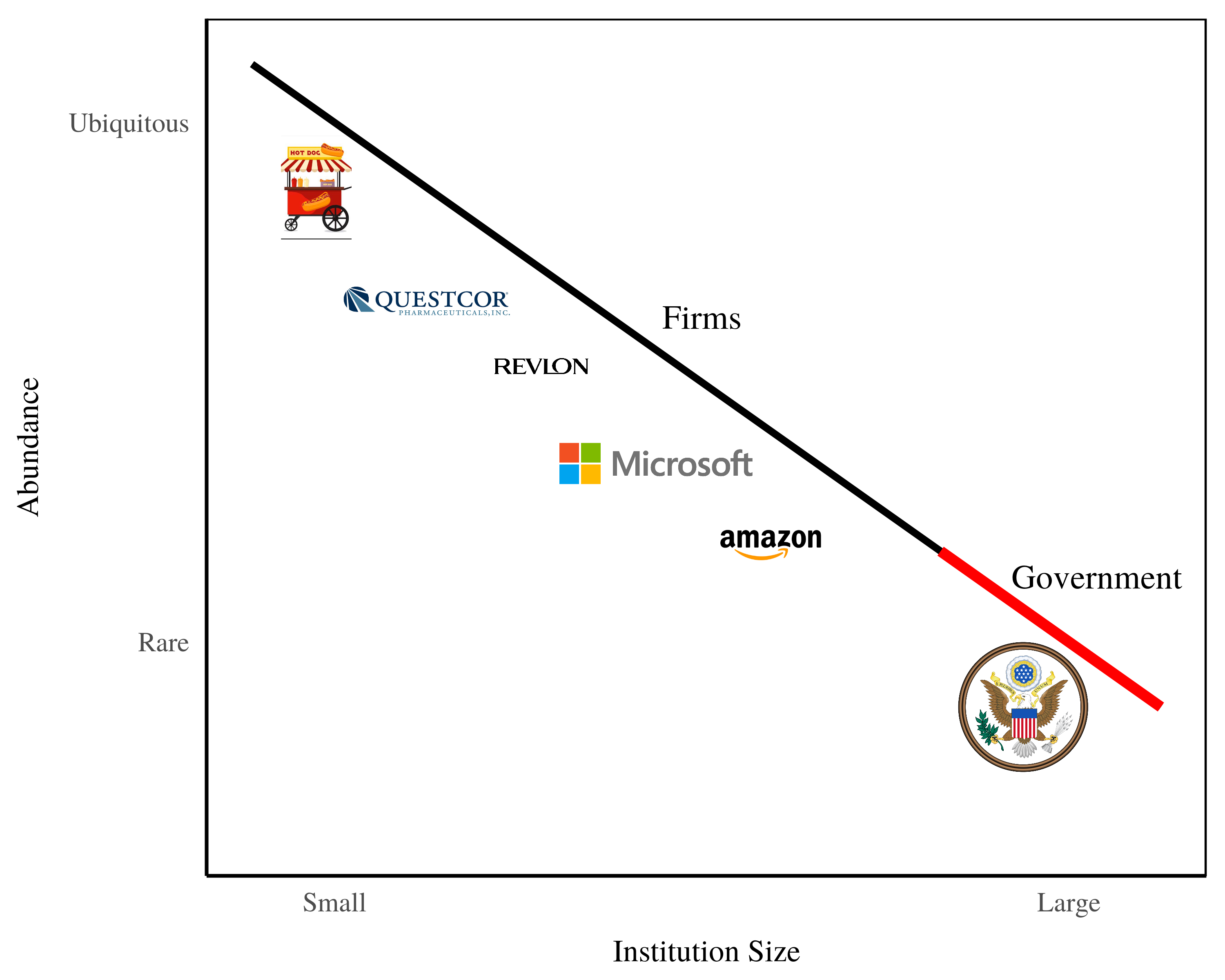

In this government-as-firm model, the vast majority of institutions are firms. But above some size threshold, firms turn into ‘governments’. Here’s a conceptual diagram:

Figure 2: The government-as-firm model

In Figure 2, I’ve labelled a few institutions to help make things concrete. At the small end of the size spectrum are self-employer firms like your favorite street-food vendor. These firms are tiny and ubiquitous.

As we move up the size ladder, we get to medium-sized firms like Questcore and Revlon. These firms have hundreds (or thousands) of employees and are fairly common.

Continuing up the size ladder, we get to large firms like Microsoft and Amazon. These firms have tens of thousands (sometimes hundreds of thousands) of employees and are quite rare.

Finally, we get to the largest institutions — governments. These beasts can have millions of employees. But they’re vanishingly rare. In the US, for instance, there are about 15 million firms [3]. But there are only about 90,000 governments. Most of these are local governments. Moving up the size ladder, the US has 50 state governments. And there’s only one federal government.

To summarize, I’m proposing that we can use the size distribution of firms to predict the abundance of government. In other words, when it comes to size, government is ‘just another firm’.

Yes, this model is a simplification

The government-as-firm model assumes a sharp line between governments and firms. Below some size threshold, every institution is a ‘firm’. Above this threshold, every institution is a ‘government’.

This is obviously a simplification.

In the real world, the line between firms and governments is blurry. Yes, governments are larger than most firms. But they’re not larger than all firms. I doubt that any US state government is larger than Walmart (which has 2 million employees). Only the US federal government tops that size. So in the real world, there’s no sharp line between firms and governments.

Still, assuming such a line exists is probably a reasonable approximation.

Since I don’t have data on the size distribution of government, I’m going to justify this assumption by analogy. Let’s return to the biomass spectrum in Figure 1. You can see that there’s no sharp line that separates mammals from non-mammals. Some mammals (like squirrels) are smaller than some non-mammals (like grouse). So a size threshold that divides mammals from non-mammals is a simplification.

But while it’s a simplification, a size threshold for mammals is a decent approximation. Looking again at Figure 1, we see that virtually all animals above 104 grams (10 kg) are mammals. Below this threshold, mammals quickly become the minority of species. So while a size threshold for mammals is a simplification, it’s also a reasonable approximation.

I’m guessing that the same is true for governments. I know that there’s no sharp line that divides firms from governments. But I hope that assuming such a line exists is a reasonable approximation. [2]

Larger firms, larger government

Now that we’ve discussed the details of the government-as-firm model, let’s get to the predictions. If government is ‘just another firm’, there’s an obvious consequence: when firms grow, government should grow too.

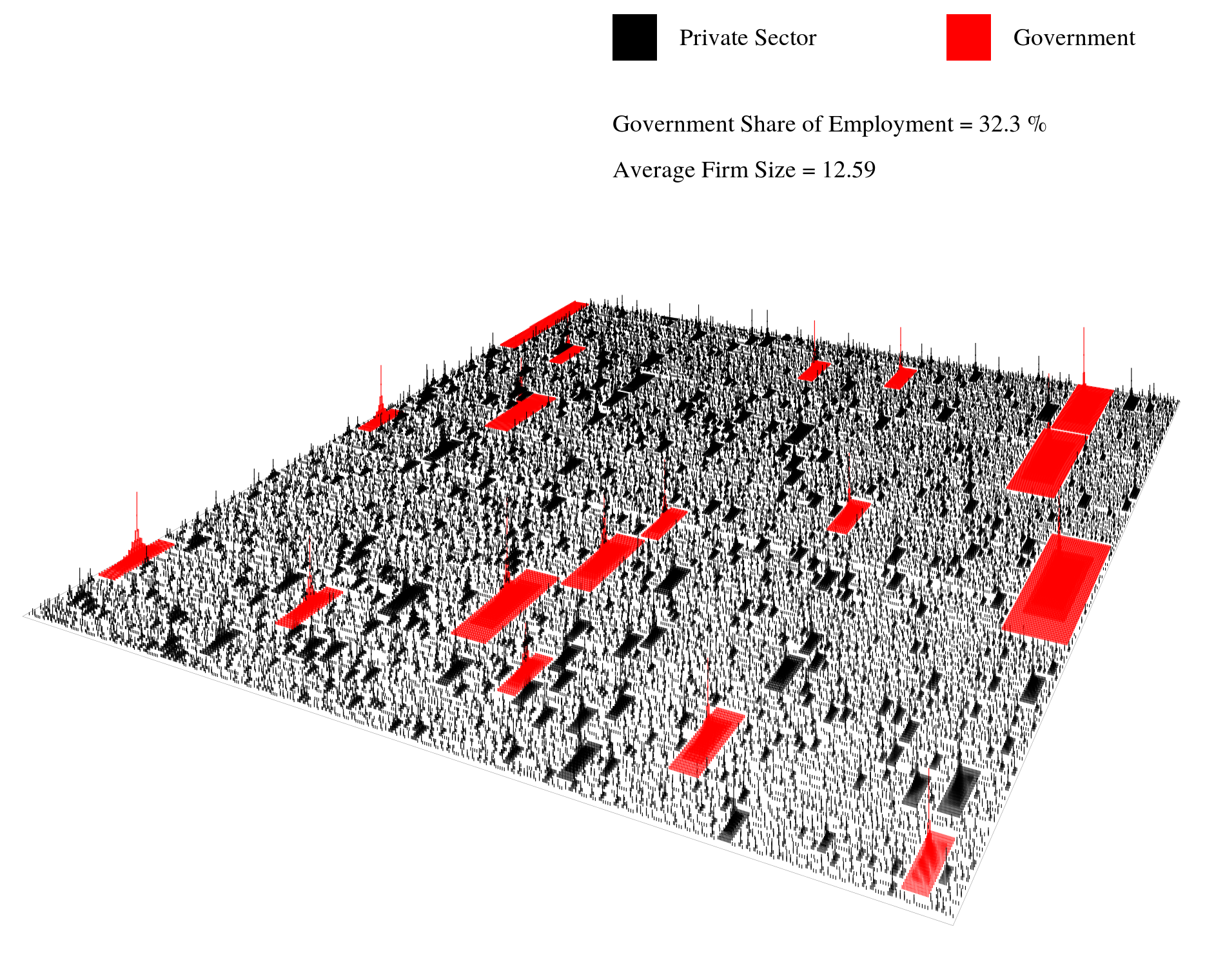

Figure 3 illustrates this prediction. Here I visualize the government-as-firm model as a landscape. Each black pyramid is a firm. Each red pyramid is a government. (I’ve assumed here that government consists of the 50 largest firms.)

Figure 3: Growing firms, growing government.

This figure shows the growth of government in the government-as-firm model. Each pyramid is an institution. Black pyramids are private-sector firms. Red pyramids are government. I model government as the 50 largest firms. From top to bottom, the size of institutions increases. As this happens, the employment share of government

increases.

From top to bottom, each panel in Figure 3 shows progressively growing firms. (For the math people, the firm size distribution follows a power law. To simulate the growth of firms, I lower the power-law exponent.) In the corner of each panel, I show the government share of employment and the average firm size. Looking at all four panels, we can see that as firms grow, the government share of employment grows as well.

So the government-as-firm model makes a clear prediction. As firms grow, government should grow too. The question is — does this actually happen in the real world?

The answer appears to be yes. As Figure 4 shows, countries with larger firms tend to have larger governments.

Figure 4: The government share of employment vs. average firm size in different countries. Each point is a country, with select countries labelled with their 3-letter code. The blue line shows the smoothed trend. Data for government employment comes from ILOSTAT series GOV_LVL_PSE (all public sector employees). Data for total employment comes from the World Bank series SL.TLF.TOTL.IN. Data for average firm size comes from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

This is an exciting result for two reasons. First, it’s not expected by mainstream economics. Nothing in mainstream theory suggests that government size should be connected to firm size.

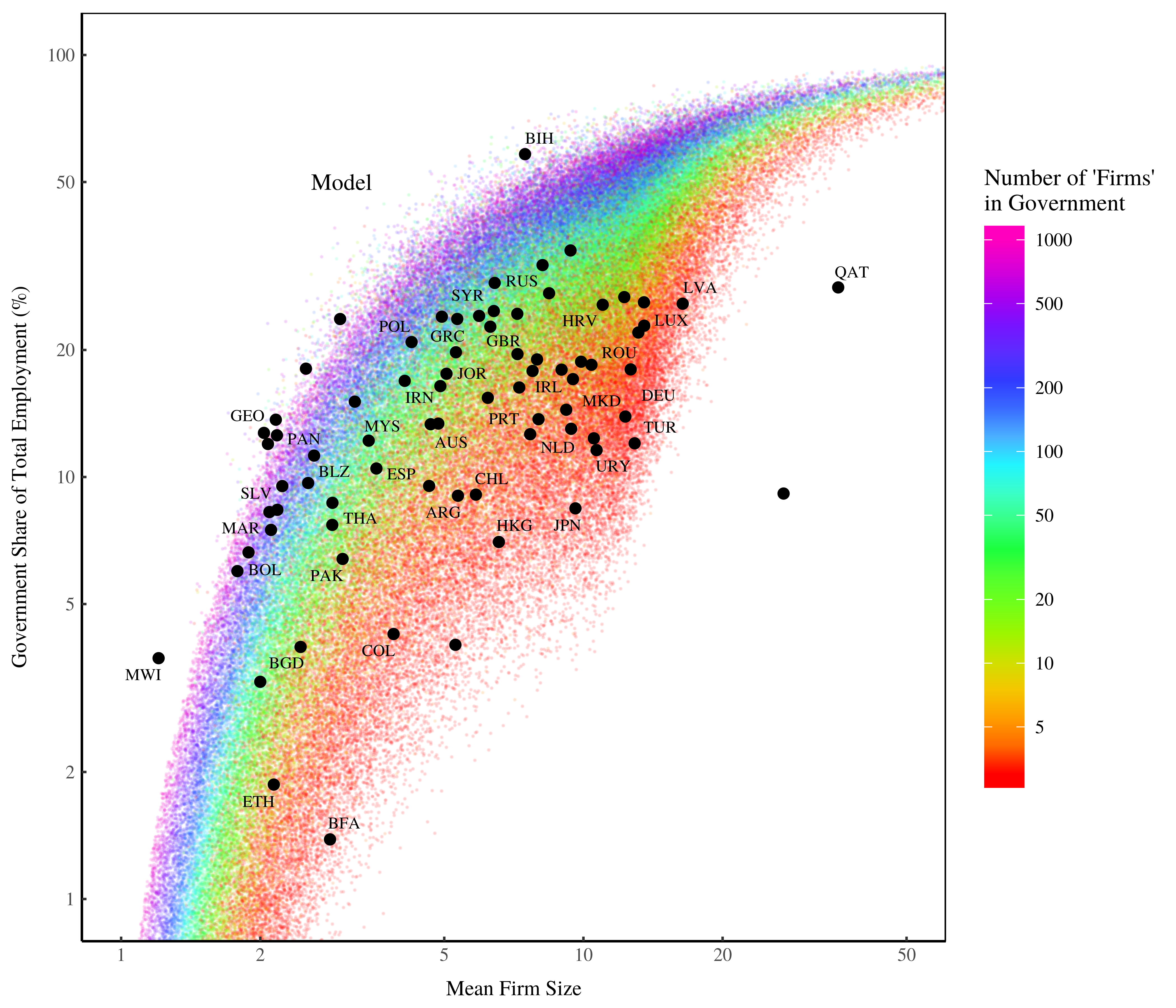

Second, this result is exciting because it matches what our government-as-firm model predicts. Figure 5 compares the growth of government and firms in the real world (black points) to the trend predicted by the model (rainbow). Only three countries are outside the model’s range (Qatar and United Arab Emirates on the right, Malawi on the left).

Figure 5: The government-as-firm model vs. real-world evidence. Real-world countries are shown in black, the model in color. The different colors indicate the number of ‘firms’ in our modeled government.

Figure 5: The government-as-firm model vs. real-world evidence. Real-world countries are shown in black, the model in color. The different colors indicate the number of ‘firms’ in our modeled government.

You’re probably wondering what the color means in Figure 5. In the government-as-firm model, government consists of the n largest firms. (I’ve labelled this parameter as the number of ‘firms’ in government. When it’s ‘200’, for instance, this means that government consists of the 200 largest ‘firms’). Since the number of ‘firms’ in government is arbitrary, I let it vary. The rainbow in Figure 5 shows this variation.

Looking at the model’s results, you can see that two things affect government size:

- The number of ‘firms’ in government

- The average size of firms

Let’s unpack this result.

How should we interpret the number of ‘firms’ in government? I treat this parameter as an outcome of political preference.

We all know that the size of government is affected by politics. Left-leaning societies let government do many tasks. Right-leaning societies let governments do few tasks. As a result, left-leaning countries have comparatively larger governments than right-leaning countries. I think of the number of ‘firms’ in government as an outcome of this preference.

Here’s an example. In the United States, healthcare is provided by the private sector. So healthcare firms aren’t part of government. But head north to Canada and this changes. In Canada, healthcare is provided by the government. So what are healthcare firms in the US become healthcare government in Canada. As a result, the Canadian government has proportionally more ‘firms’ than the US government. Again, this amounts to a political preference. Canadians like big government. Americans do not.

But in addition to this political preference, there’s a larger trend at work. The size of government seems to be connected to the size of firms. When firms grow, government grows. This connection is unexpected by mainstream economics. It’s also unexpected by theories of politics. But it makes perfect sense if government is ‘just another firm’. If governments are the largest firms, it’s obvious that as firms grow, government should grow too.

The demographer and the biologist

Although I’m a political economist, I often tire of the myopia of the field. It’s not that this myopia is bad. It’s okay to get engrossed in the grit of human politics. But sometimes this prevents you from seeing the big picture.

Most political economists are like population demographers. Demographers delve into the details of population density, trying to understand the subtle differences between societies. In the same vein, political economists dissect the minutia of human politics. This fine-grain study is admirable. It’s a key part of science. But it’s not the only part. Sometimes science requires a wide lens.

Enter the biologist.

Unlike the demographer, the biologist isn’t concerned with the details of human population density. Instead, the biologists steps back and looks at all life on Earth. By doing so, the biologist realizes that human abundance fits into a larger trend. Like all other organisms, human abundance is predictable from our size. Yes, industrial humans are more abundant than our hunter-gatherer brethren. But in the grand scheme of life, this difference is a fudge factor. If you want to predict human abundance, you don’t need demography. You need a bathroom scale.

In this post, I’ve played the biologist. I’ve argued that when it comes to understanding government size, political economists are missing the big picture. They’ve focused mostly on politics — and for good reason. Political debates about the proper role (and hence size) of government dominate our lives. But by focusing on this debate, political economists have missed the larger trend, which is this: when it comes to abundance, government behaves like it’s just another firm.

Notes

[1] Sources and methods for human abundance. Humans have an average mass of 62 kg. In Figure 1, I’ve plotted three population densities: (1) the density of the density city; (2) the average density of modern humans; (3) human density during prehistory.

According Wikipedia, Manila is the densest city on Earth, with 46,178 people per square km (0.046 per square meter). To get the average density of modern humans, I’ve divided the human population (7.8 billion) by Earth’s land area (148 million square km). That puts the average density of industrial humans at about 5 × 10-5 people per square meter. To get the density of humans in prehistory, I do the same calculation but replace human population with 10 million — the upper estimate on Wikipedia for the human population 10,000 years ago. That puts ancestral human density at about 6 × 10-9 people per square meter.

Sources and methods for blue whale abundance. I estimate the mass and abundance of blue whales using data from Wikipedia. Adult blue whales range from 50,000 to 150,000 kg. The blue whale population is between 10,000 to 25,000. I estimate blue-whale density by dividing the whale population by the area of Earth’s oceans (360 million square kilometers). The four points in Figure 1 represent the four combinations of mass and population estimates.

[2] We won’t know if a size threshold for government is a good approximation until we measure the size distribution of government. This is something I intend to do in the future. On that note, if you know where I can get data on the size (number of employees) of local US governments, leave a comment.

[3] According to the US Census Business Dynamics Statistics, there are about 5 million firms in the US. But this doesn’t include people who are self-employed but unincorporated. There’s about 10 million of these people. Including them brings the total number of firms to roughly 15 million.

Further reading

Hatton, I. A., Dobson, A. P., Storch, D., Galbraith, E. D., & Loreau, M. (2019). Linking scaling laws across eukaryotes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(43), 21616–21622.