Why Scorcese is right about corporate power, Part 1

August 16, 2021

Originally published at notes on cinema

James McMahon

What is more pleasurable: reading Martin Scorcese on cinema or reading reactions to Scorcese on cinema? The reactions compete for our pleasure because they reveal how easy it is for someone’s words to make us jump into a debate with two feet and eyes closed.

In the March 2021 issue of Harper’s, Scorcese wrote an essay to pay tribute to Federico Fellini, the Italian director who directed such great films as La Strada, 8 1/2, La Dolce Vita, Nights of Cabiria and Satyricon. Scorcese writing on Fellini is definitely newsworthy for cinephiles who want to know about Fellini’s beginnings in Italian neo-realism (for example, he worked with Rosselini on Rome, Open City), or who simply want to be reminded of why his filmography is so great. However, the news of this essay’s arrival went well beyond film studies and had very little to do with Fellini. News outlets reported the publishing of the essay and #scorcese trended on Twitter because Scorcese framed his tribute to Fellini–which was both personal and knowledgeable–with an argument about the decline of cinema as an art form. Here is a key example from the essay’s conclusion:

Everything has changed—the cinema and the importance it holds in our culture. Of course, it’s hardly surprising that artists such as Godard, Bergman, Kubrick, and Fellini, who once reigned over our great art form like gods, would eventually recede into the shadows with the passing of time. But at this point, we can’t take anything for granted. We can’t depend on the movie business, such as it is, to take care of cinema. In the movie business, which is now the mass visual entertainment business, the emphasis is always on the word “business,” and value is always determined by the amount of money to be made from any given property–in that sense, everything from Sunrise to La Strada to 2001 is now pretty much wrung dry and ready for the “Art Film” swim lane on a streaming platform.

Jump-cut to a crowd of people who vehemently agree with Scorcese. They recite the names of directors from the past, in the hopes that people will understand the magnitude of what will be lost if cinema goes extinct. A reverse shot of another angry crowd, who believe Scorcese is over-reacting to cinema’s future. Some in this crowd might dislike his characterization of streaming platforms like Amazon Prime, and the recommendation-through-algorithm method. Others might be skeptical of the argument that art is being crushed inside the corporate packages that deliver media content.

I strongly support Scorcese’s essay. But I also think that my form of support is slightly different than others. Through a curious survey of #scorcese after the Harper’s essay, I noticed that much of the digital debate is used to re-state definitions of cinema and art. (Scorcese, for his part, produced his own version of “What is Cinema?” before the Harper’s essay, when he said Marvel superhero films were movies but not cinema.) My support for Scorcese is based on a deep appreciation for the artistic potential of films, but it is also based on the significance of this claim: “We can’t depend on the movie business, such as it is, to take care of cinema.”

A reader might have skimmed over this sentence, or perhaps it was grouped with all the other pieces of Scorcese’s argument for the preservation of cinema. But if we pause on the sentence “We can’t depend on the movie business, such as it is, to take care of cinema”, we can see there is something perplexing about it. Would we say this about other industries, such that we have sentences like:

- We can’t depend on the steel business, such as it is, to take care of steel production.

- We can’t depend on the aviation business, such as it is, to provide safe air travel.

- We can’t depend on the pharmaceutical business, such as it is, to provide useful medicine.

Researchers and journalists on steel, air travel and pharmaceutical medicine might reply with reasons why you can definitely say these things about their respective business sectors. My point, rather, is a simpler one. Scorcese is revealing a truth that is not taught to those of us who grew up under capitalism: that a business has an antagonistic relationship with what it is purportedly in business to produce. An implication of this truth is that, with respect to the art of cinema, the film business does not want another Fellini, Antonioni, Varda, Godard, Ackerman, Scorcese, ….

In a multi-part post, I want to show how Scorcese is right about the differences of circumstance, which exist between himself and a director like Fellini. I also want to use Scorcese’s argument as a platform to widen our perspective on the political economy of Hollywood. The story Scorcese is telling about the business of Hollywood is a story about business interests wanting to reduce risk. The ambiguity of risk in this story–is it financial risk or is it aesthetic risk?–is a helpful shortcut to understanding what reducing risk means for those who have control over the industrial art of filmmaking. When the Hollywood film business is estimating its future earnings, risk perceptions account for the possibility that the future of culture will be different–and perhaps radically different–from what capitalists expect it to be. This logic of capitalist accounting, while quantitative in expression (prices, income, volatility, etc.), is social in essence. For this reason, the capitalization of cinema cannot overlook any social dimension of cinema, be it aesthetic, political or cultural. The eye of capitalization searches for any social condition that could have an impact on “the level and pattern of capitalist earnings” (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009, p. 166).

Part 1 will introduce Scorcese’s concern and situate it within the method I will use to analyze the financial performance of the major Hollywood studios.

Nostalgia for a business that likes risky cinema

As mentioned above, Scorcese’s shows little restraint to let his celebration of Fellini celebrate the art of cinema more broadly. For instance, Scorcese sees Fellini as one the leaders in a cadre of filmmakers that were willing to explore every potential within cinematic art. Like Bresson, Godard and others, Fellini was open to letting a film tell a story in the best way it could.

Scorcese also makes a point to give his admiration to the old film business, or at least some part of it, which was willing to support this cinema renaissance:

The choices made by distributors such as Amos Vogel at Grove Press back in the Sixties were not just acts of generosity but, quite often, of bravery. Dan Talbot, who was an exhibitor and a programmer, started New Yorker Films in order to distribute a film he loved, Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution–not exactly a safe bet. The pictures that came to these shores thanks to the efforts of these and other distributors and curators and exhibitors made for an extraordinary moment. The circumstances of that moment are gone forever, from the primacy of the theatrical experience to the shared excitement over the possibilities of cinema. That’s why I go back to those years so often.

Fellini and his contemporaries could not have long careers without financial support. But if that is the case, what changed? Have these “brave” beneficiaries disappeared? Who replaced them?

Hollywood needs to differentially accumulate

In the trenches of independent filmmaking, nothing has changed: producers scramble for money and people with money take a risk and invest in a film project that might not be purchased by a distributor. These producers might also sell future distribution rights for advanced funding–so if the film is a hit down the road, the lender is the one getting rich.

However, in the broader world of the film business, a lot has changed. Financing a film for profit is the core of business enterprise, but the significance of that profit changes when you are, for example, competing to reach the same levels as Fortune 500 companies.

To illustrate the change let us look at an extreme comparison of investment in cinema. George Harrison of The Beatles was one of the key financiers of Monty Python’s Life of Brian. The comedy troupe was in need of around $4 million to begin shooting and Harrison stepped in to help. This amount of money is not insignificant, and we do not need to assume that Harrison, famous as he was, could afford to lose his investment. However, listen to members of Monty Python recount the financing of Life of Brian and it is hard to imagine that Harrison was as serious as a capitalist–e.g., benchmarking his investment against alternatives or trying to find the Beta coefficient of Monty Python–even though he took a clear risk in his personal wealth.

At the other end of this comparison is an example of Hollywood’s historical performance: in 1996 the average operating income per firm of the major film distributors was $504 million. For the same year, its average revenues per firm were $4.5 billion. Are these magnitudes large or small? Now consider other relevant questions. How would investors, who could always put money in sectors other than film and media, regard these numbers? How does Hollywood know if it is doing well or not? When is the financial performance of cinema cause for celebration, and when is it a reason for distress? There are no universal answers to these questions, but Harrison was not even seeking such answers. He might enjoy a return on his investment, but he is investing in a project that corporations rejected. He was also not telling Monty Python that he could invest in Life of Brian, or oil, or plastics, or insurance stocks, or US bonds, etc..

The modus operandi of actual capitalists is to find and use contextually-relevant benchmarks for the performance of their investments:

A capitalist investing in Canadian 10-year bonds typically tries to beat the Scotia McLeod 10-year benchmark; an owner of emerging-market equities tries to beat the IFC benchmark; investors in global commodities try to beat the Reuters/Jefferies CRB Commodity Index; owners of large US corporations try to beat the S&P 500; and so on. Every investment is stacked against its own group benchmark—and in the abstract, against the global benchmark. (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009, p. 309)

Relevancy, in this case, is defined by such factors as listed stock exchange and the size of the investment. As an oligopoly of cinema, major Hollywood film distribution finds like-minded competition in the giant firms around the world and in their respective sectors. Their levels of accumulation are worthy benchmarks of the powerful capitalist.

When the risk of investing in cinema is compared to investment in the rest of capitalist universe–oil, weapons, grain, cars, etc.–it is entirely possible that corporate love for risky cinema can disappear. In fact, if we place Scorcese’s argument within a general history of cinema, we can see there is an overlap of two events:

- Hollywood’s heavy reliance on blockbuster cinema;

- the change in how Hollywood film distributors accumulate capital, relative to dominant firms across other sectors.

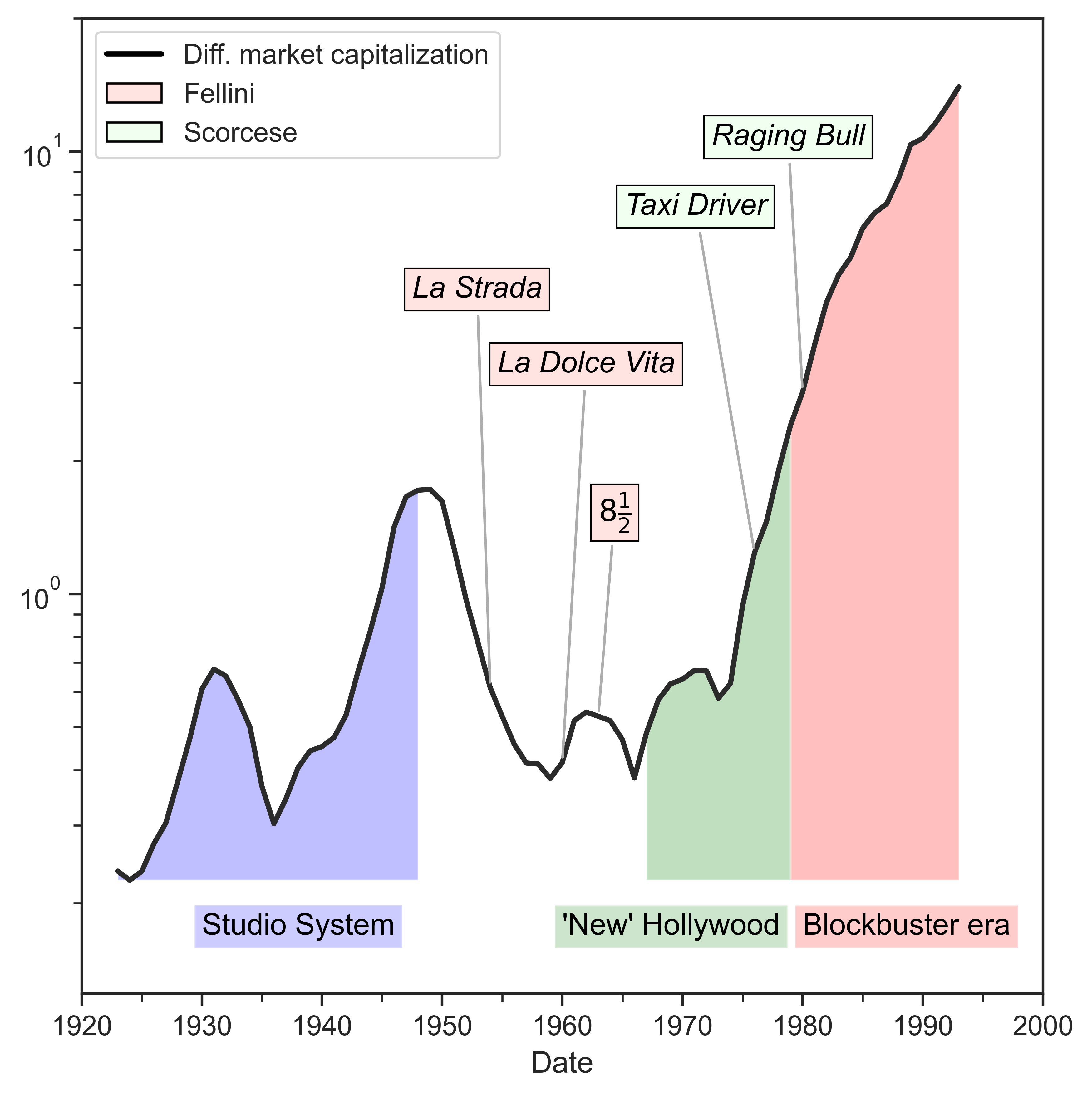

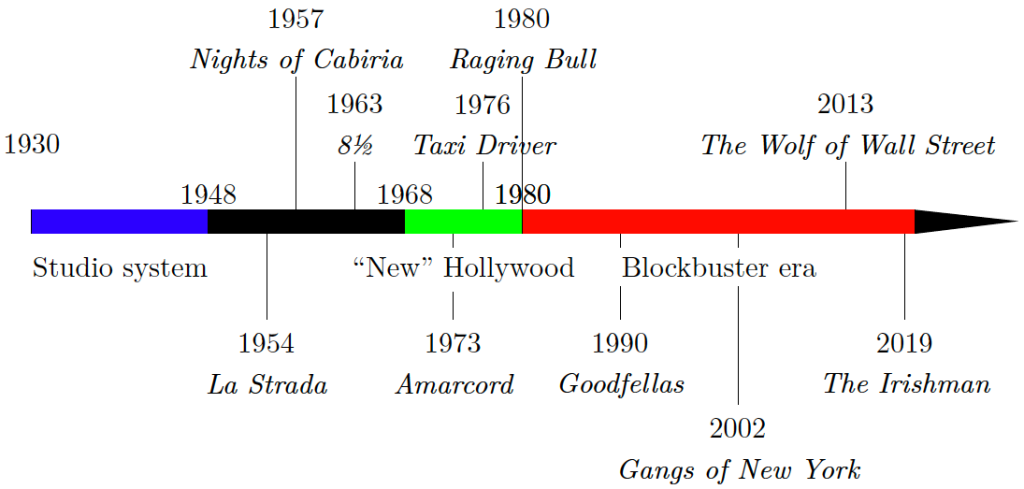

We can simplify our presentation for the sake of showing this overlap of aesthetic trends and business strategies clearly. Figure 1 places selected films from Fellini and Scorcese on a broad timeline of Hollywood history. The three major eras in this timeline are the studio system, “New” Hollywood and blockbuster cinema. The studio system is not directly relevant to our topic, but it is perhaps still the most controversial era of Hollywood history. The key distribution-exhibition strategies of the studio system, such as “block booking”, were dismantled by the 1948 US Supreme Court case United States v Paramount Pictures. “New” Hollywood does not have definitive start and end points–we are setting it at 1968 and 1980, respectively. This era is famously Hollywood’s counter-cultural phase, when it hired younger directors to speak to such issues as the Vietnam War, the Hippie movement, civil rights, Women’s Liberation, Richard Nixon and state surveillance. The young Scorcese graduated from NYU and started building his directing career in this era. The blockbuster era, like “New” Hollywood, has no official start date. 1980 is a simple marker because it signifies the beginnings of Hollywood privileging blockbusters over everything else. Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) were released before 1980, but, with hindsight, we can see the sector-wide push that followed; Hollywood initiated a new era because it was hungry to find that next Jaws and that next Star Wars, and on and on.

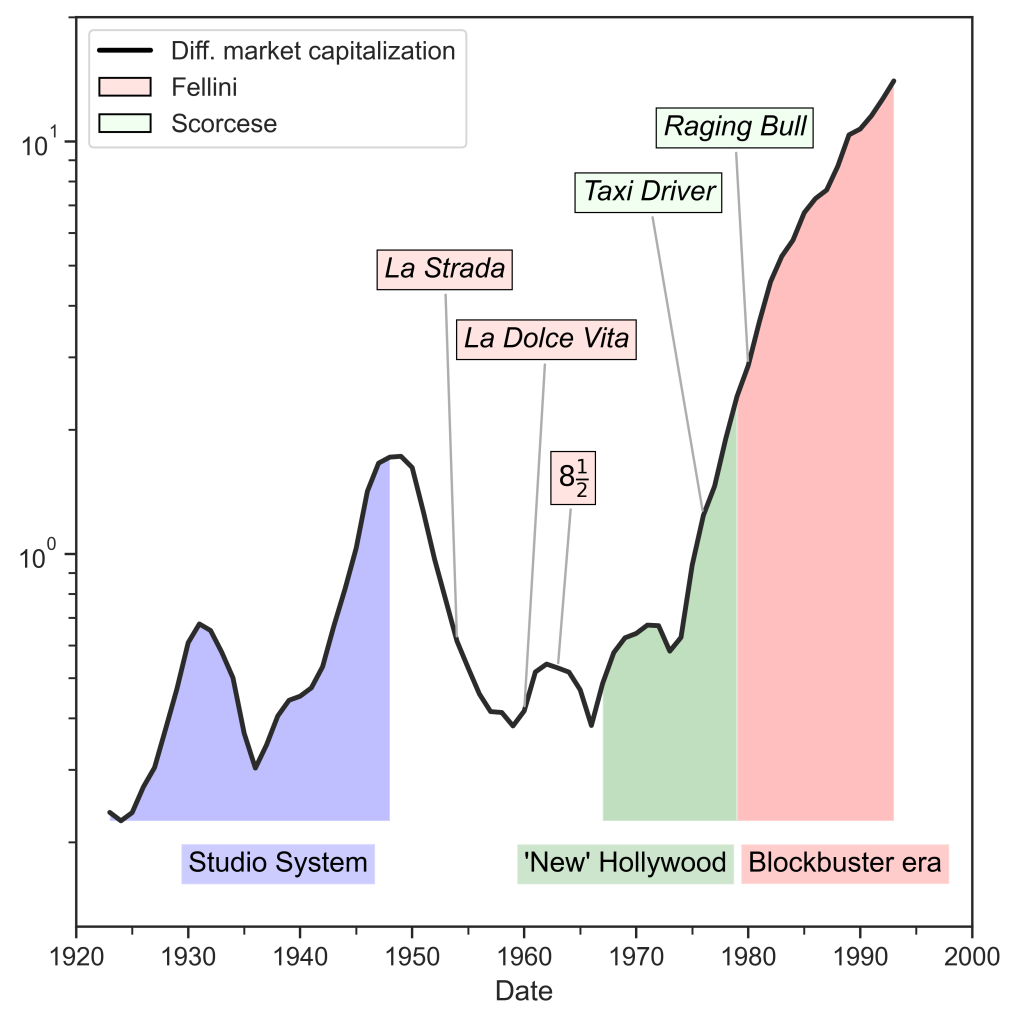

Figure 2 has our cinema timeline overlap a measure of Hollywood’s differential capitalization. According to Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, differential capitalization is a symbolic representation a capitalist trying to accumulate more than a relevant benchmark of capital (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009).[1] For example, differential accumulation occurs when the capitalization of A rises faster than its benchmark or falls slower than a falling benchmark. In this figure we measure the differential accumulation of Hollywood with the capitalization per firm of major Hollywood distributors (Columbia, Paramount, RKO, Twentieth Century-Fox, Universal, and Warner Bros.)[2], divided by the per firm average market capitalization of all US-listed firms.

Perceived as a story of differential accumulation, the differential rises of Hollywood occurred during its notable “eras”. The rise and fall of the studio system is visible in Figure 2. “New” Hollywood was also a strong period of differential accumulation.[3] The brief embrace of Leftist counter-culture enabled Hollywood to effectively reverse the depression between 1948 and the early 1960s. From there, the blockbuster cinema launched Hollywood to new heights. Without any long-term de-acceleration, blockbuster-Hollywood increased its differential capitalization 390% from 1980 to 1993.

Note: Series is smoothed as a 5-year moving average. Source: Global Financial Data for market capitalization of Warner Brothers, Paramount Pictures, RKO, Universal Pictures, Twentieth-Century-Fox, and Columbia Pictures Industries Inc. to 1956. Compustat through WRDS for market capitalization 1956-1993. Global Financial Data for US total market capitalization and number of firms. US market capitalization per firm is calculated by dividing the total value by the number of firms.

Next post: The change to Hollywood’s accumulation

1993 is a funny year for the time series of Figure 2 to end. The reason is related to conglomeration and the usage of firm-level data. My data sources switch to annual reports in the early 1990s because various financial databases (Compustat, Global Financial Data) do not have business segment data, which is needed when we need to isolate film production and distribution from a conglomerate’s other business operations. Therefore, the market capitalization of a conglomerate is just as misleading when, for example, a firm also invests in theme parks (Disney), wind turbines (GE), or radio stations (News Corp).

Notwithstanding its termination in 1993, the dataset is long enough to show that Hollywood kept beating a US benchmark when it switched to a blockbuster-centric strategy. The next post will analyse how this success is related to Scorcese’s issue with contemporary Hollywood. To preview the relation, see Figure 3. In this figure, the benchmark is the 500 largest firms in the Compustat database, measured each year and sorted by market capitalization. The 500 firms are a proxy for the S&P 500, which is a standard benchmark for the biggest firms in the world. When you can repeatedly beat the S&P 500, you reside in the dominant class.

Like Figure 2, the differential market capitalization of Hollywood rose in the era of “New” Hollywood and continued to rise into the blockbuster era. However, differential operating income fell in the early years of the blockbuster era and then continued to fall over the long term. And unlike the parallelism that occurred during “New” Hollywood, major Hollywood firms in the blockbuster era were not able to beat our 500-firm benchmark in both market capitalization and profits. How does differential market capitalization rise when differential profits trend downward? The answer, we will see, is risk reduction.

Note: Both series are smoothed as 5-year moving averages. Source: Compustat through WRDS for market capitalization and operating income, 1950-1993. Compustat for operating income of Hollywood firms, 1950-1993. Annual reports of Disney, News Corp, Viacom, Sony, Time Warner (Management’s Discussion of Business Operations for information on their filmed entertainment interests) for operating income, 1994-2019.

TO BE CONTINUED …

Further reading

McMahon, J. (2013). The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema. Review of Capital as Power, 1(1), 23–40.

McMahon, J. (2015). Risk and Capitalist Power: Conceptual Tools to Study the Political Economy of Hollywood. The Political Economy of Communication, 3(2), 28–54.

McMahon, J. (2019). Is Hollywood a risky business? A political economic analysis of risk and creativity. New Political Economy, 24(4), 487 – 509. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1460338

Notes

[1] The accumulation of what? Power. I will unpack this claim in future posts. Currently I am, for the sake of brevity, glossing over a key piece of Bichler and Nitzan’s theory of capital accumulation. Lots of writing on the capital-as-power approach appears on http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/ and https://capitalaspower.com.

[2] If you are interested in a detailed breakdown of my data, see (McMahon, 2019). Each firm does not appear every year. Disney is not included in the average market capitalization because its valuation includes more business operations than film production and distribution.

[3] While not spoken of in terms of capitalization and differential accumulation, many histories of Hollywood present “New” Hollywood as a period when studios reversed their bad fortunes and became profitable again. See, for example, Cook (2000); Kirshner (2012); Langford (2010).

References

Cook, D. A. (2000). Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate, 1970-1979 (C. Harpole, Ed.) (No. 9). New York: C. Scribner.

Kirshner, J. (2012). Hollywood’s Last Golden Age: Politics, Society, and the Seventies Film in America. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Langford, B. (2010). Post-classical Hollywood: Film Industry, Style and Ideology Since 1945. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

McMahon, J. (2019). “Is Hollywood a risky business? A political economic analysis of risk and creativity”. New Political Economy, 24(4), 487 – 509. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2018.1460338

Nitzan, J., & Bichler, S. (2009). Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder. New York: Routledge.