Jeffrey Williamson’s Terms of Trade

October 2, 2021

Originally published at joefrancis.info

Joe Francis

Jeffrey Williamson‘s (2011) book Trade and Poverty: When the Third World Fell Behind is one of the most interesting attempts to explain the ‘great divergence’ between rich and poor countries. It is a shame, then, that it is marred by his use of Mickey Mouse numbers.

In simplified terms, Williamson argues that a long terms-of-trade boom made the periphery deindustrialise in the nineteenth century. Improved terms of trade undercut import-competing proto-industrial sectors, while capital and labour instead focused on primary-commodity production for export.

According to Williamson, specialisation led to the great divergence because (1) ‘industrial-urban activities contain far more cost-reducing and productivity-enhancing forces than do traditional agriculture and traditional services’ (2011, p. 49); (2) specialisation led to a ‘resource curse’ that saw the periphery’s institutions come to reflect the interests of the rent-seeking elites that were the principal beneficiaries of primary-commodity exports (2011, pp. 50-51); and (3) there was more growth-inhibiting volatility because primary-commodity prices fluctuate more dramatically than those of manufactured goods (2011, pp. 51-53). Williamson’s new narrative thus has the long terms-of-trade boom generating divergence by dividing the world into an industrialised core and a poor, deindustrialised periphery that was afflicted by bad institutions and great instability.

Williamson (2008) supports his narrative with a data set of the terms of trade of numerous peripheral countries. This empirical aspect of his work has been widely applauded. One prominent reviewer, for example, states that a ‘major contribution of Williamson’s research is the compilation of a data set on the terms of trade for 21 poor countries’ (Crafts 2013, p. F193). Yet, as will be seen in this post, this data set should not be taken seriously.

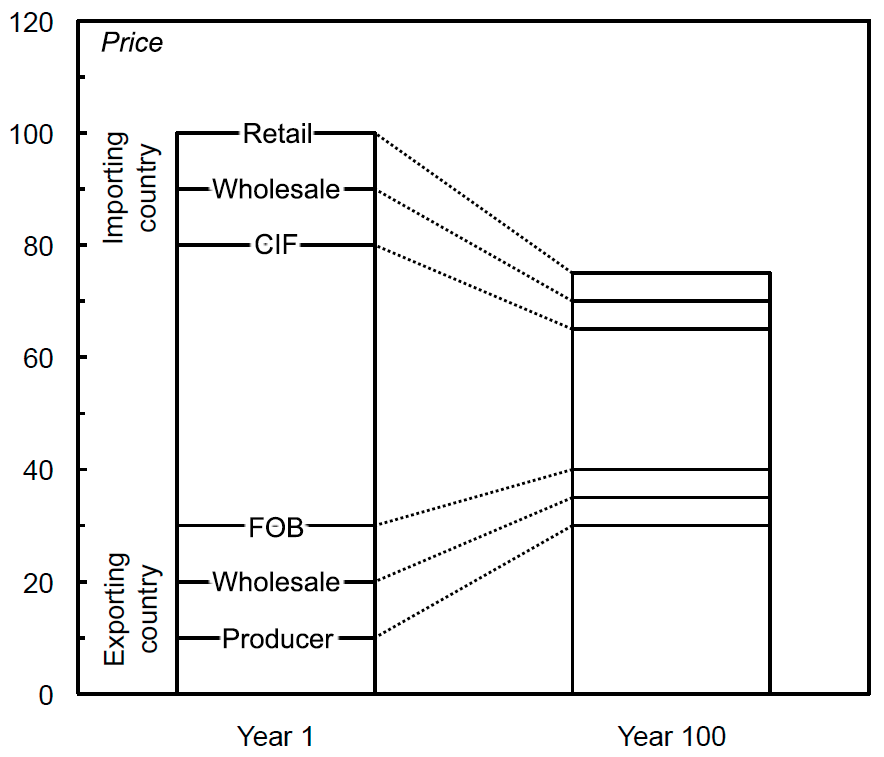

The problems with the periphery’s terms-of-trade data is that there are few price data for the peripheral countries themselves, so prices from the core countries must be used as proxies. These prices will be misleading to the extent that trade costs between the core and periphery change. Figure 1, for example, provides a notional illustration of what happens when trade costs fall. The prices of a country’s exports in the importing country drop, even as they rise at home. At the same time, the prices of its imports rise in the exporting country, even as the prices fall at home. Hence, any terms of trade calculated using the other country’s prices will have a downward bias in the trend.

Figure 1: Prices of an Internationally-Traded Good with Falling Trade Costs

Note: The figure shows the notional price of an internationally-traded good. It shows how falling trade costs can mean that the domestic price of a country’s exports can go up, even as the price of that same good falls in the importing country.

WIlliamson (2011, p. 29) himself is aware of this problem. He describes the ‘ideal measure’ of a country’s terms of trade as being calculated using its own prices, whereas the ‘worst-case scenario’ uses prices from other countries. Williamson claims, however, that the problem does not seriously affect his data set. He writes:

‘Having pointed out the flaws in the worst-case scenario, it should be stressed that there are only 6 of these (out of 21) [in his data set]. The other 15 are taken from country-specific sources and do an excellent job in constructing estimates that come close to the ideal measure […]’. (Williamson 2011, p. 29)

To check this claim, I examined the sources for all 21 of Williamson’s series as part of my doctoral research. I found that only two were calculated following Williamson’s ‘ideal measure’ – that is, using prices from the peripheral countries themselves. By contrast, fully 12 were constructed entirely from prices from the core countries; three used core prices for imports; two used core prices that were adjusted for changes in transportation costs; the final two appeared to be of little value because their sources were dubious (see Francis 2013, Appendix 2.1).

Williamson’s claim about the quality of his data therefore seems misleading to say the least. Why this matters can be seen in Figure 2. Here, what Williamson calls the ‘ideal measure’ estimates (the thick lines) are compared with the ‘worst-case scenario’ estimates (the thin lines). The result clearly shows the downward bias in the trend of the latter. Indeed, in four out of six cases the ‘worst-case scenario’ terms of trade have a downward, whereas the ‘ideal measure’ has an upward trend. It is difficult, therefore, to take his data set seriously.

Figure 2: Terms of Trade, 1860s-1913

Note: The thick lines are what Williamson calls ‘ideal measure’ terms of trade, the thin lines are ‘worst-case scenario’ terms of trade. The annual trends are calculated as the rate of change of the exponential trend line. Sources: Ho (1930); Taylor and Michel (1931, pp. 18-19); Hou (1965, pp. 194-98); Glazier, Bandera, and Berner (1975, pp. 30-33, Table 5); Yamazawa and Yamamoto (1979, pp. 169-70, 193, 197); Korthals Altes (1994, pp. 158-60); data underlying Blattman, Hwang, and Williamson (2007), available online; data underlying Williamson (2008), kindly provided by Professor Williamson; Federico and Vasta (2009, pp. 22-23, Table 2).

Given these flaws in Williamson’s data set, some of his results must be rejected as unreliable. Most notably, in Chapter 11, which draws on an earlier article by Christopher Blattman, Jason Hwang, and Williamson (2007), the dubious terms-of-trade estimates are fed into econometric models to demonstrate the ‘globalisation and great divergence connection’. My research into WIlliamson’s data suggests that none of the results reported in that chapter can be relied upon, although it is important to note that my findings strongly reinforce his core narrative, as they indicate that the periphery’s terms-of-trade boom was considerably greater that he has suggested.

References

Blattman, C., J. Hwang, and J.G. Williamson, ‘Winners and Losers in the Commodity Lottery: The Impact of Terms of Trade Growth and Volatility in the Periphery 1870-1939’, Journal of Development Economics, 82:1, 2007, pp. 156-79.

Crafts, N.F.R., ‘Book Review Feature: Trade and Poverty: When the Third World Fell Behind’, Economic Journal, 123, 2013, pp. F193-97.

Federico, G., and M. Vasta, ‘Was Industrialization an Escape from the Commodity Lottery? Evidence from Italy, 1861-1940’, Dipartimento di Economia Politica Quaderno 573, Università degli Studi di Siena, 2009.

Francis, J.A., ‘The Terms of Trade and the Rise of Argentina in the Long Nineteenth Century’, PhD diss., London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013.

Glazier, I.A., V.N. Bandera, and R.B. Berner, ‘Terms of Trade Between Italy and the United Kingdom 1815–1913’, Journal of European Economic History, 4:1, 1975, pp. 5-48.

Ho, F.L., Index Numbers of the Quantities and Prices of Imports and Exports and of the Barter Terms of Trade in China, 1867-1928, Tientsin, 1930.

Hou, C., Foreign Investment and Economic Development in China 1840-1937, Cambridge, MA, 1965.

Korthals Altes, W.L., Changing Economy in Indonesia: A Selection of Statistical Source Material from the Early 19th Century up to 1940, XV, Prices (Non-Rice) 1814–1940, Amsterdam, 1994.

Taylor, K.W., and H. Michel, Statistical Contributions to Canadian Economic History, II, Toronto, 1931.

Williamson, J.G., ‘Globalization and the Great Divergence: Terms of Trade Booms, Volatility and the Poor Periphery, 1782-1913’, European Review of Economic History, 12:3, 2008, pp. 355-91.

_____, Trade and Poverty: When the Third World Fell Behind, Cambridge, MA, 2011.

Yamazawa, I., and Y. Yamamoto, Estimates of Long-Term Economic Statistics of Japan since 1868, XIV, Foreign Trade and Balance of Payments, Tokyo, 1979.