- This topic has 12 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated February 16, 2022 at 6:21 pm by .

-

Topic

-

My interest in the topic of the relation between money, finance, and state power stems from my experience of entering into adulthood in the United States in the aftermath of the 2007 financial crash, feeling intensely the socially disruptive effects (and affects) of this event, and coming to the conclusion that it might be in my interest to attempt to understand them.

Colin Drumm, The Difference that Money Makes: Sovereignty, Indecision and the Politics of Liquidity

Thus, from the jump, Drumm identifies the nexus of his inquiry as being firmly aligned with CasP’s, but his (and his dissertation’s) focus on “money as a thing” is something that, to my knowledge, CasP theory has largely ignored in preference for studying finance, the domain of capital.

As we know, CasP theory is premised, in part, on the observation that, “in the real world, the quantum of capital exists as finance, and only as finance,” but I would argue all capital begins as money, and Drumm’s work demonstrates that pre-capitalist money is of particular importance to understanding the state of capital as well as the nature of capital itself (and how it came to become power).

I previously discussed one of the more innovative ideas in the first chapter of Colin’s book. This time, I want to refer you to an innovation he introduces in Chapter Two: the idea of pre-capitalist money as an “option,” specifically as an “option to rebellion.”

NOTE: Drumm does not use the term “pre-modern” money. His focus is on medieval money in the form of coins made of gold or silver, but he draws a temporal border between money as it was before the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694, and as it became thereafter (“modern money”). Importantly, he views the formation of the Bank of England (and the creation of modern money) as a solution to a political crisis, and he argues that understanding that historical crisis is critical to understanding modern money in a way that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) studiously ignores to everyone’s detriment. Drumm is no fan of MMT.

The term “option” as used by Drumm is a financial one, and if you accept his thesis that pre-modern money was an option, then money and finance were one and the same before 1694, a fact that had several consequences that Drumm explores at length.

Drumm’s conclusion that pre-modern money represented a financial (and political) option is based on the recognition that pre-modern coins minted of gold or silver had two different values: the currency (or nominal) value and the metal (or intrinsic) value. Within its country of circulation (the “inside” option or bid), the currency value of a minted coin always exceeded the metal value, i.e., a coin nominally worth a pound sterling always contained less than a pound sterling of silver because the sovereign (including his mint) charged a percentage for exchanging specie for currency. Different countries/sovereigns charged different exchange rates, giving rise to “spreads” between sovereigns (the “outside” option or ask). If a spread between sovereigns (inside and outside options) achieved a “breaking point” for either gold or silver coins, one sovereign could “attack” the other’s mint in a way that siphoned gold and/or silver to the attacker.

Why does any of this, as interesting as it is, matter? Because the fundamental nature of pre-modern money put the king and other elites in conflict with each other. Money was necessary to fund wars, but it was also necessary to create a national economy, i.e., a tax base. During war, medieval nations ran a deficit, but during peace, to prepare for the next war the king had to hoard the very source of wealth that was the basis of the economy: money. Taking silver and gold money out of circulation naturally depressed the economy (and pretty much explains why there is no reason we should even think about calculating GDP for pre-modern societies), but it also was done largely at the elites’ expense. This was true even during the era of “agrarian capitalism” that stretches into the early 16th century.

The simple truth is pre-modern money inhibited economic growth because its function as a medium of exchange competed with its function as a store of value, and the latter function always won because the harm caused by a lack of economic growth was born primarily by the commoners (or proletariat).

The question was, who should benefit from the stored value, the king, or the elites he was trying to tax? As Drumm argues, pre-modern money (money as finance/capital) gave the elites the option to rebel instead of paying money as taxes. And what a glorious thing the English Revolution of 1688 was.

So this brings us to modern money and how it broke with its predecessor, pre-modern money.

Drumm recognizes that we are asked to view modern money as if it were pre-modern money, that is, as a thing that “has the three functions of being a store of value, medium of exchange, and unit of account.” But he rejects this characterization of modern money:

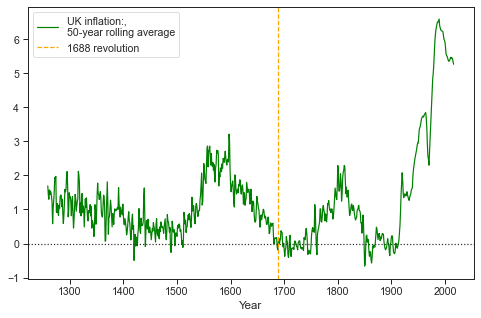

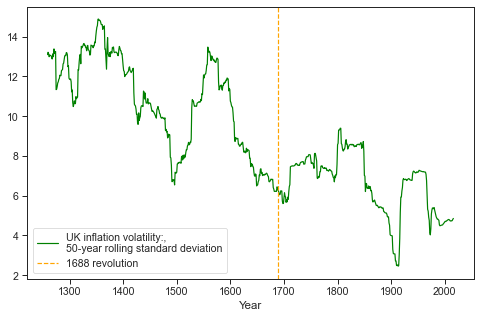

Believing this requires an active suspension of attention to what there really is. It is clear even to a casual observer of 20th century monetary history that “money” has not served as a particularly good or reliable store of value given the numerous and sometimes infamous episodes of both abrupt and secular inflations which characterize the period. This seemingly clear falsification of the concept can, however, be ideologically recuperated by identifying this situation as an anomalous state of affairs which differs from how money “should be” according to its essential concept. In the liberal narrative, the failure of 20th century monetary systems to be a store of value is a symptom of the folly of populism and the inherent danger of any and all state power over money, while in Marxist narratives it is the result of a progressive abstraction of the monetary symbol from its material commodity substrate, taken to be gold. In both theories there is the sense that the past is a past of commodity money, in which money has a natural equilibrium due to its articulation with the real in the form of the metallic essence, while the present is the present of paper money which has “lost touch” with the real of Value and therefore has been stripped of its capacity to store it.

I would argue that the advent of modern money cleaved the function of storing value from the concept of “money” and assigned it to accounting (financial) records, i.e., to capital. While both money and capital reflect the same unit of account, currency, modern money serves as the medium of exchange for commodities, capital serves as the medium of exchange for financial (capital) assets, and only capital serves as a store of value. In this way, modern money allows wealth (power) to be accumulated as capital without removing money from circulation and harming the commodity market, what most think of as the “real” economy. Simultaneously, the accumulated wealth (capital) is used as the medium of exchange in the “fictitious” financial economy to control the real economy.

NOTE: the capital markets are just as Leibnitzian as the commodity markets, but in a way that is determined by the quantum of capital already possessed by participants, not by their liquidity preference (which affects annualized rates of return, not the opportunity to participate in differential accumulation).

Anyway, Drumm’s work seems important to both MMT and CasP, but for different reasons. MMT needs to reconsider whether the modern “normal” is worth keeping within the broader context of what else changed beyond the change in the nature of money . The money-capital duality enforces inequality and needs to be reconsidered, not embraced (hint: look at the history of taxation and the nature of what is taxed). Similarly, CasP needs to consider the interaction between money and capital, which are related but not the same. According to the rules of capitalism, the power of capital can be constrained through its relationship to money, but only if we fully understand that relationship.

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.