Free Speech For Me, Not You

May 13, 2022

Originally published at Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

They say that Americans love two things: freedom … and guns. The trouble with guns is obvious. The trouble with freedom is more subtle, and boils down to doublespeak.

When a good old boy defends his ‘freedom’, there’s a good chance he has a hidden agenda. He doesn’t want freedom for everyone. He wants ‘freedom for himself, not you’. I call this sentiment freedom tribalism. It’s something that, given humanity’s evolutionary heritage, is predictable. It’s also something that has gotten worse over the last few decades. And that brings me to the topic of this essay: free speech.

When the talking heads on Fox News advocate ‘free speech’, they’re using doublespeak. What they actually want is free speech for their own tribe … and censorship for everyone else. This free-speech tribalism extends far beyond the swill of cable news. It’s clearly visible (and growing worse) in the pantheon of high thought — the US Supreme Court.

To make sense of this free-speech tribalism, we need to reframe how we understand ‘free speech’. And that means reconsidering the idea of ‘freedom’ itself. Behind freedom’s virtuous ring lies a dark underbelly: power. Free-speech tribalism, I’ll argue, amounts to a power-struggle between groups — a struggle to broadcast your tribe’s ideas and censor those of the others. When you look closely at this struggle, it becomes clear that ‘free speech’ is not universally virtuous. In modern America, free speech has become a kind of slavery.

And with those incendiary words, let’s jump into the free-speech fire.

Fire!

FIRE! Fire, fire… fire. Now you’ve heard it. Not shouted in a crowded theatre, admittedly, … but the point is made.

That was the inimitable Christopher Hitchens addressing the elephant in every free-speech room: shouting fire in a crowded theatre. The metaphor has come to symbolize speech that is so ‘dangerous’ it must be censored. It’s a fair example, since people have actually died from false shouts of fire in crowded theatres.1 But more often than not, the shouting-fire metaphor is used to justify censorship of a more dubious kind.

Woodrow Wilson got the ball rolling during World War I. After declaring war on Germany, Wilson embarked on a campaign to silence internal dissent. Among the thousands of Americans who were prosecuted was Charles Schenck, a socialist convicted of printing an anti-draft leaflet. His case went to the Supreme Court. Writing to uphold the conviction, Justice Oliver Holmes claimed that war critics like Schenck were, in effect, falsely shouting fire:

The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. … The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.

(Oliver Wendell Holmes, Schenck v. United States)

Holmes’ decision set off a long debate about what types of speech represent a ‘clear and present danger’. I won’t wade into the details. Instead, what I find more interesting is the language that is missing here. Holmes speaks about ‘free speech’, ‘danger’, and ‘evils’. But what is really at stake is the government’s power.

Holmes admits as much in a less-cited part of his ruling. Schenck’s anti-draft leaflet was dangerous, Holmes noted, precisely because it undermined the government’s power to make war:

It denied the [government’s] power to send our citizens away to foreign shores to shoot up the people of other lands …

(Oliver Wendell Holmes, Schenck v. United States)

So there you have it. The idea of ‘falsely shouting fire’ was used to bolster the government’s power to wage war.

Free speech for views you don’t like

The lesson from the Schenck case is that reasonable forms of censorship inevitably get used to justify more dubious types of speech suppression. To combat this creeping censorship, free-speech advocates like Noam Chomsky argue that we must do something that feels reprehensible — defend freedom of speech for views we despise:

f you believe in freedom of speech, you believe in freedom of speech for views you don’t like. Goebbels was in favour of freedom of speech for views he liked, right? So was Stalin. If you’re in favour of freedom of speech, that means you’re in favour of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise. Otherwise you’re not in favour of freedom of speech.

(Noam Chomsky in Manufacturing Consent)

Chomsky’s position is elegant, principled and more than just words. It’s a maxim he lives by. And that has gotten him into all sorts of trouble. You can imagine the uproar, for instance, when Chomsky defended the free speech of historian Robert Faurisson, a Holocaust denier. More recently (and to the delight of the far right), Chomsky drew leftist ire for signing a Harper’s editorial warning of a “stifling atmosphere” in modern America that was “narrow[ing] the boundaries of what can be said without the threat of reprisal.”

In the face of this criticism, however, Chomsky remains unphased. He is a tireless advocate for the right to espouse ideas he finds despicable.

Free-speech tribalism

If everyone was as principled as Chomsky, the world would probably be a better place. But the reality is that Chomsky is an outlier. Most people find it difficult to separate the right to free speech from the speech itself. Rather than criticize this tendency, though, we should try to understand it. And that means studying ‘free speech’ in the context of human evolution.

If evolutionary biologists David Sloan Wilson and E.O. Wilson are correct, human evolution has been strongly shaped by ‘group selection’. That means we evolved as a social species that competed in groups. The result is that humans have an instinct for group cohesion in the face of competition — an us-vs-them mentality. In other words, humans are tribal.

When it comes to ‘free speech’, this tribalism plays out predictably. Humans behave exactly the way Chomsky says we should not. We support free speech for ideas we like, and censorship for ideas we dislike.

Take, as an example, Donald Trump. After Trump delivered his incendiary speech that stoked the storming of the Capitol, Twitter decided they’d had enough. They permanently banned Trump from their platform. How did Americans feel about this ban? Support fell predictably along partisan lines (Figure 1). Democrats overwhelmingly supported Twitter’s Trump ban. Republicans overwhelmingly opposed it. This tribal divide isn’t rocket science. When the shit hits the fan, instincts trump abstract principles.

Commentary on the Trump ban focused mostly on the content of his speech. Was he stoking ‘imminent lawlessness’? Or was he [cue incredulous cough] ‘defending democracy’? These are important questions. But what I find more interesting is what seemed to go undiscussed.

It’s one thing for a President to silence his critics. That’s state censorship. It’s another thing for critics to silence a President. That’s called accountability. The difference has nothing to do with the content of the speech. Instead, it comes down to power. When the weak censor the powerful, it’s different than when the powerful censor the weak.

Granted, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey is hardly ‘the weak’. But the principle remains. Power dynamics should affect how we interpret ‘censorship’. When the government censors an obscure Neo-Nazi, that’s probably bad. But what if Nazis run the government? Should citizens let the Nazi regime broadcast propaganda on the grounds that it is ‘free speech’?

If so, George Orwell was right. Freedom is slavery.

Free-speech tribalism on the US Supreme Court

Back to free-speech tribalism. On the individual level, the game is about free speech for me, not you. But at the group level, it’s about us versus them. Free speech for my tribe, not your tribe.

Since Americans’ right to free speech is written in the constitution, free-speech tribalism has played out most prominently in the US Supreme Court — the institution that determines how the constitution is interpreted. Of course, Supreme Court justices all claim to believe in free speech for everyone. But their behavior tells a different story.

In a landmark study, Lee Epstein, Andrew Martin and Kevin Quinn tracked how US Supreme Court justices ruled on cases concerning free speech. Importantly, Epstein and colleagues distinguished between two factors:

- the partisanship of the justices;

- the political spectrum of the speech on trial.

Figure 2 shows Epstein’s results — a quantification of 6 decades of free-speech rulings on the Supreme Court.

It’s clear, from Figure 2, that there is a tribal game afoot. Let’s spell it out. If Supreme Court justices were following Chomsky’s ideal (free speech for ideas you like and those you despise) then the red and blue lines in Figure 2 would overlap. Democratic and Republican justices would support free speech to the same degree, regardless of the content of the speech. That clearly doesn’t happen.

Instead, Supreme Court justices are following the ‘tribal ideal’ — free speech for ideas they like … censorship for ideas they despise. Hence Democratic justices support liberal speech more than Republican justices (Figure 2, left). And Republican justices support conservative speech more than Democratic justices (Figure 2, right).

Given humanity’s evolutionary background, this tribalism is not surprising. What’s interesting, though, is that Supreme Court tribalism hasn’t been constant. Instead, it’s grown with time.

In the Warren court of the 1950s and 1960s, there was remarkably little free-speech tribalism. Justices of both parties overwhelmingly supported free speech of all kinds, with only a slight preference for the speech of their own tribe. Today, that’s changed. In the Roberts court of the 21st century, not only have justices of both parties become less tolerant of free speech in general, there is now a glaring tribal bias. Democratic justices support liberal speech far more than Republican justices. And Republican justices support conservative speech far more than Democratic justices.

It is tempting to blame both political parties for this tribalistic turn. But the reality is that the blame rests overwhelmingly on Republicans. Figure 3 tells the story. I’ve plotted here the partisan bias in support for free speech. This is the difference in support for speech made by ‘your tribe’ versus support for speech made by the ‘other tribe’. Let’s start with the Democratic tribe. While Democratic justices have become less tolerant of free speech in general (Fig. 2), they have not become more biased. Instead, for the last 6 decades, Democratic justices have had a slight but constant bias for liberal speech.

Now to the Republican tribe, where the story is quite different. Once less biased than Democrats (during the Warren court), Republican justices now show overwhelming bias for conservative speech. In the Roberts court, Republican justices support conservative speech over liberal speech by a whopping 44%.

Free speech for us, not them.

Free speech for business

Republican bias for ‘conservative’ speech isn’t the only way that the US Supreme Court has become more tribal. The court has also become more biased towards the business tribe.

The most seismic case in this pro-business shift was Citizens United. In this 2010 decision, the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to limit corporate spending on political campaigns. The majority’s reasoning was simple:

- people have free speech;

- corporations are legal persons;

- therefore, corporations have free speech.

Citizens United opened the floodgates of corporate electioneering. The reality, though, was that this case was part of a larger pro-business shift on the Supreme Court — a shift that coincided with a reversal of fortune for US corporations.

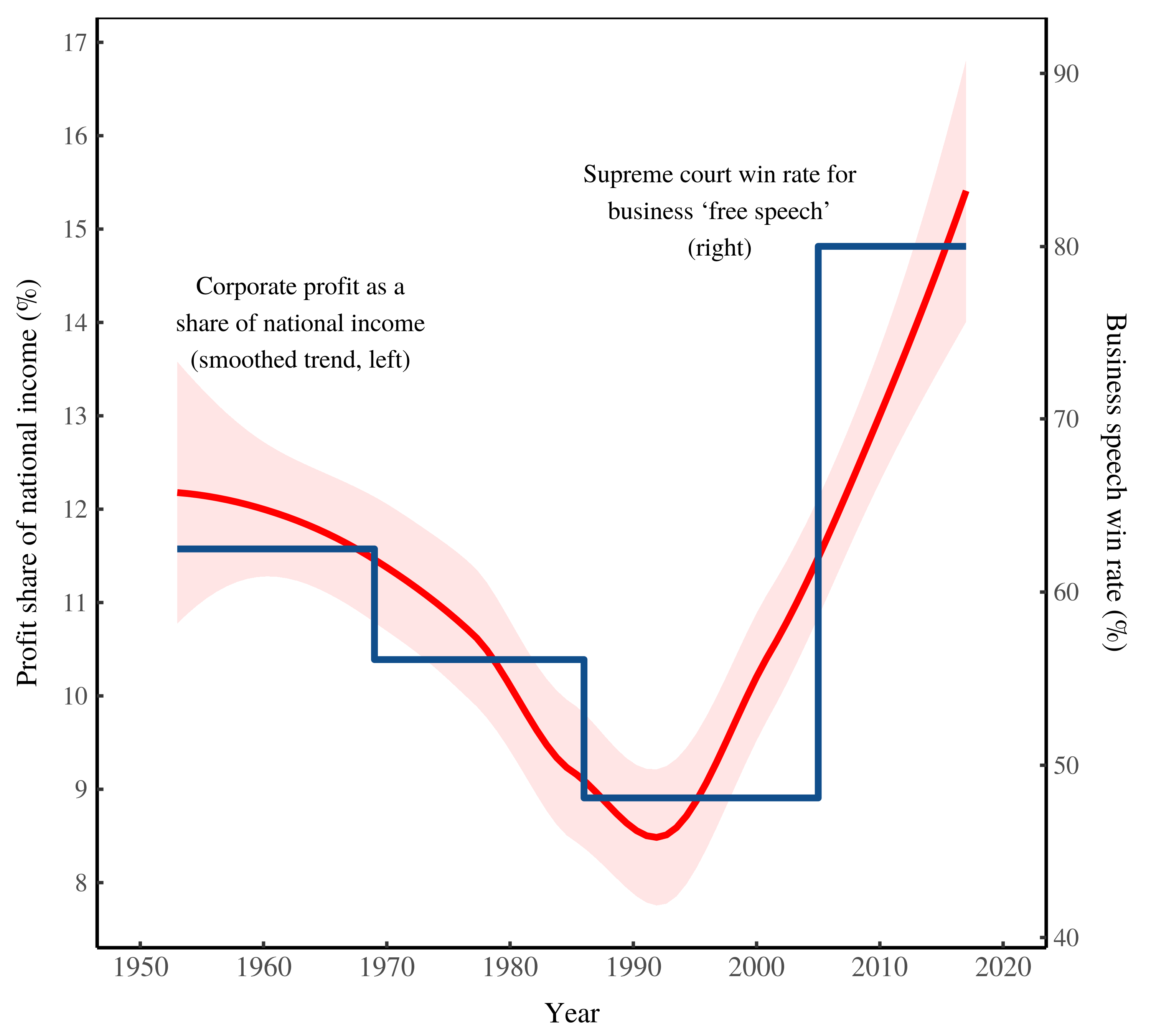

Figure 4 tells the story. From the 1950s to the 1990s, US corporations had a problem. Although they had no trouble making profits in absolute terms, the profit share of the pie tended to decrease. (See the red curve in Fig. 4.) Then came a stunning reversal of fortune. From the mid-1990s onward, corporate profits boomed, eating up an ever increasing share of the US income pie.

This reversal of fortune coincided with a change in the Supreme Court’s attitudes towards ‘free speech’. Until the 1990s, the Court was increasingly hostile to ‘free speech’ for business. As a result, the ‘win rate’ for business free speech declined steadily. Then came the Roberts court, which brought relief for the business tribe. Over the last decade and a half, the Roberts court sided with business in a whopping 80% of free-speech cases.

Unsurprisingly, in this pro-business environment, profits boomed. ‘Free speech’ for corporations means wage slavery for workers.2

The trouble with ‘freedom’

The triumph of business propaganda (and the corresponding boom in corporate profits) shouts at us to reconsider some basic moral principles. Ask yourself — is ‘free speech’ universally virtuous? I think the answer has to be no.

The problem with ‘free speech’ boils down to a basic contradiction in the idea of ‘freedom’ itself. In a social world, freedom for everyone is impossible. The reason is simple. Freedom has two dimensions: ‘freedom to’ and ‘freedom from’. These two dimensions are always in opposition. For example:

- If you are free to shout racist slurs, your neighbour cannot be free from such slurs.

- If you are free to smoke anywhere, your friends cannot be free from second hand smoke.

- If you are free to drive through a red light, fellow motorists cannot be free from T-bone collisions.

You get the picture. There are two sides to being ‘free’, and they are always in mutual conflict. When you think about this conflict, you realize that ‘freedom’ always involves power:

- If I am ‘free to’ shout racist slurs, I have the power to suppress your ‘freedom from’ such slurs.

- If I am ‘free from’ hearing racist slurs, I have the power to suppress your ‘freedom to’ shout racist speech.

When we look at this power behind ‘freedom’, we realize that ‘freedom’ cannot be universally virtuous. One man’s freedom is always another man’s chains.

Resolving conflict with property rights

If the two sides of freedom are always in opposition, we need a way to resolve the ensuing conflict. In capitalist societies, the main way we do this is by defining property rights. These are legal principles that delineate which type of freedom wins out, and when and where it does so.

A key purpose of property rights is to restrict ‘freedom to’. In other words, property rights restrict ‘free speech’. For example, if someone enters my property and shouts racist slurs, I don’t have to listen. Instead, my property rights give me the power to have the culprit removed by the cops. On my property, my ‘freedom from’ trumps your ‘freedom to’. In other words, my property gives me the power to censor.3

Is this power a bad thing? Probably not, at least in principle. To see why, imagine a world in which ‘freedom to’ always trumped ‘freedom from’. In this world, if someone wanted to insult you in your living room, you’d have to let them. It would be an Orwellian nightmare in which solitude was impossible. So having a space where ‘freedom from’ trumps ‘freedom to’ is undoubtedly a good thing.

That said, when we scale up private property, the power to censor becomes more dubious. Suppose that instead of owning a house, I own a corporation. This is a very different type of property. Rather than own space, I own an institution — a set of human relations. With this more expansive type of property, I suddenly have much more power to censor. If my employees wanted to unionize, for instance, I could ban ‘union propaganda’. I could go further and ban any speech critical of me, the supreme leader. It would be a Stalinist dream … for me. For my employees, would be a totalitarian nightmare.

Let’s flip sides now and look at the other side of property. While private property suppresses ‘freedom to’, public property suppresses ‘freedom from’. On public property, my ‘freedom to’ speak trumps your ‘freedom from’ my speech. So when I stand on a street corner, I am free to shout racist slurs. Passersby must endure my slander. In other words, on the street, I have the power to broadcast.

The street-corner ability to broadcast is, admittedly, a weak form of power. Everyone else has the same power, so they can drown me out if they want. (This is the principle of public protest.)4 But notice what happens if we treat the ‘public domain’ more broadly, not as the street-corner, but as the space between corporations. In a world in which corporations have free speech, there is no respite from corporate propaganda. It’s a world in which freedom-loving Americans now live.

Freedom is just another word for …

The problem with the debate about free speech boils down to the language of ‘freedom’ itself. When ‘freedom’ becomes synonymous with virtue, the debate becomes vacuous. Saying “I stand for freedom” is like saying “I stand for happiness.” Who’s going to argue with you?

Okay, I’ll argue with you. If murdering people makes me happy, my ‘happiness’ is not virtuous. It is sadistic. Likewise, if I am ‘free’ to murder people I dislike, my ‘freedom’ is not virtuous. It is depraved.

The same goes for ‘free speech’. It is virtuous in some contexts, but not others. Unfortunately, there is no simple way to determine when and where ‘free speech’ is good, and when and where it is bad. Like so many things in life, it is a matter of opinion. But a useful tool is to look at the underside of ‘freedom’. When you see the words ‘free speech’, substitute the language of power:

I stand for

free speechthe power to broadcast.

With this revised language, the virtue of ‘free speech’ becomes more ambiguous. If the substitution gives you a bad feeling, that’s a sign there is doublespeak at work. Sometimes freedom really does mean slavery.

Sources and methods

Data for US corporate profits is from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.12. I’ve taken corporate profits before tax (without IVA and CCAdj) and divided by national income.

Notes

- Some shouting-fire examples. In 1902, a crowd at the Shiloh Baptist Church (in Birmingham Alabama), misheard ‘fight!’ for ‘fire!’ The ensuing stampede killed over 100 people. In 1913, the Italian Hall in Calumet, Michigan was filled with striking miners. Someone shouted ‘fire!’, causing a stampede that killed 73 people. The miners suspected that the perpetrator was a strike breaker, but no one was ever charged.↩

- Mainstream economics is mute about how profits relate to the law. That’s probably because if you study the law, you realize that it (not ‘productivity’) is the foundation of corporate profits. A century ago, heterodox economist John R. Commons explored this connection in his book Legal Foundations of Capitalism. He was largely ignored.↩

- The word ‘censorship’ has, for good reasons, acquired a negative connotation. But it seems clear that some forms of censorship are good — perhaps even essential to maintaining a healthy dialogue. Rather than ‘censorship’, a better word for this act is ‘moderation’. Social critic Keith Spencer proposes a rule of thumb: ‘unmoderated online forums always degenerate into fascism’. This is a hyperbole, but probably contains a kernel of truth. When there is no moderation, expect a creep not to high philosophy, but to base-level urges.↩

- A note on free-speech tribalism. I once met a Jordan Peterson fan who was incensed that Peterson’s speaking event (in Toronto) was besieged by protesters. “Let Peterson have free speech!” he demanded. The Peterson acolyte didn’t seem to understand that he was advocating censorship … for the protesters. No matter, they weren’t in his tribe.↩

Further reading

Commons, J. R. (1924). Legal foundations of capitalism. London: Transaction Publishers.

Epstein, L., Martin, A. D., & Quinn, K. (2018). 6+ decades of freedom of expression in the US supreme court. Preprint, 1–17.