What if the Government is Just Another Firm? (Part 2)

September 25, 2020

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

Governments are different than firms, right?

Perhaps not.

In Part 1 of this series, I argued that when it comes to size, governments behave like they’re ‘just another firm’. In this post, I’m going to extend the evidence. I’ll first show you that as economies develop, governments get bigger. Then I’ll explain this trend using the ‘government-as-firm’ model.

Schrodinger’s government

Before we get to the data on government size, let’s ask a simple question: is big government necessary for economic development?

Neoclassical economists answer no. They think that ‘perfect competition’ is the best way to achieve growth. So what’s the role of government? In neoclassical theory, government is like Schrodinger’s cat — it both exists and does not exist. Government (implicitly) exists because ‘perfect competition’ requires property rights. And who enforces these rights? Government. At the same time, government does not exist, in neoclassical theory, because perfectly-competitive markets are supposedly ‘self-correcting’. So there’s no need for government intervention.

Confused yet? You should be. The neoclassical treatment of government makes little sense as a scientific theory. But it makes perfect sense as an ideology. Its purpose is to discourage public central planning. Here’s how Paul Walker puts it:

[T]he “perfect competition” model … has its intellectual origins in the eighteenth-century debate between free traders and mercantilists. This debate wasn’t about competition, in any meaningful sense … it was about the proper scope of government in an economy.

… The central question of the debate was, Is central planning necessary to avoid the problems of a chaotic economic system? Adam Smith famously answered no.

With this history in mind, let’s return to our question: is big government necessary for economic growth? Neoclassical theory answers no. Instead, it claims that smaller government is better for the economy. If this is true, then governments should shrink as the economy grows.

It’s politics, stupid!

The flip side of Schrodinger’s government is the political view held by some social scientists. In this view, the size of government stems mostly from politics.

There’s an obvious truth to this approach. The big government of the Soviet Union obviously stemmed from communist politics. And the (comparatively) small government of the US stems from free-market politics.

But is political ideology the only determinant of government size? I’m skeptical. Yes, politics matter. But there are limits to putting ideas in action. Think of it this way. An ant can’t will itself into becoming an elephant. Likewise, I’m skeptical that an undeveloped society can will itself into having a big government. Physical constraints make this impossible.

But maybe I’m wrong. If I am — if government size stems from politics alone — then the size of government shouldn’t relate to economic development.

Government size: the evidence

So we have two different predictions for how government size should relate to economic development. If neoclassical theory is correct, government will get smaller as the economy grows. If the political view is correct, government size won’t relate to economic growth.

Both predictions, it turns out, are wrong. Governments don’t shrink with economic growth. Nor is government size unrelated to economic growth. Instead, as the economy grows, governments get larger.

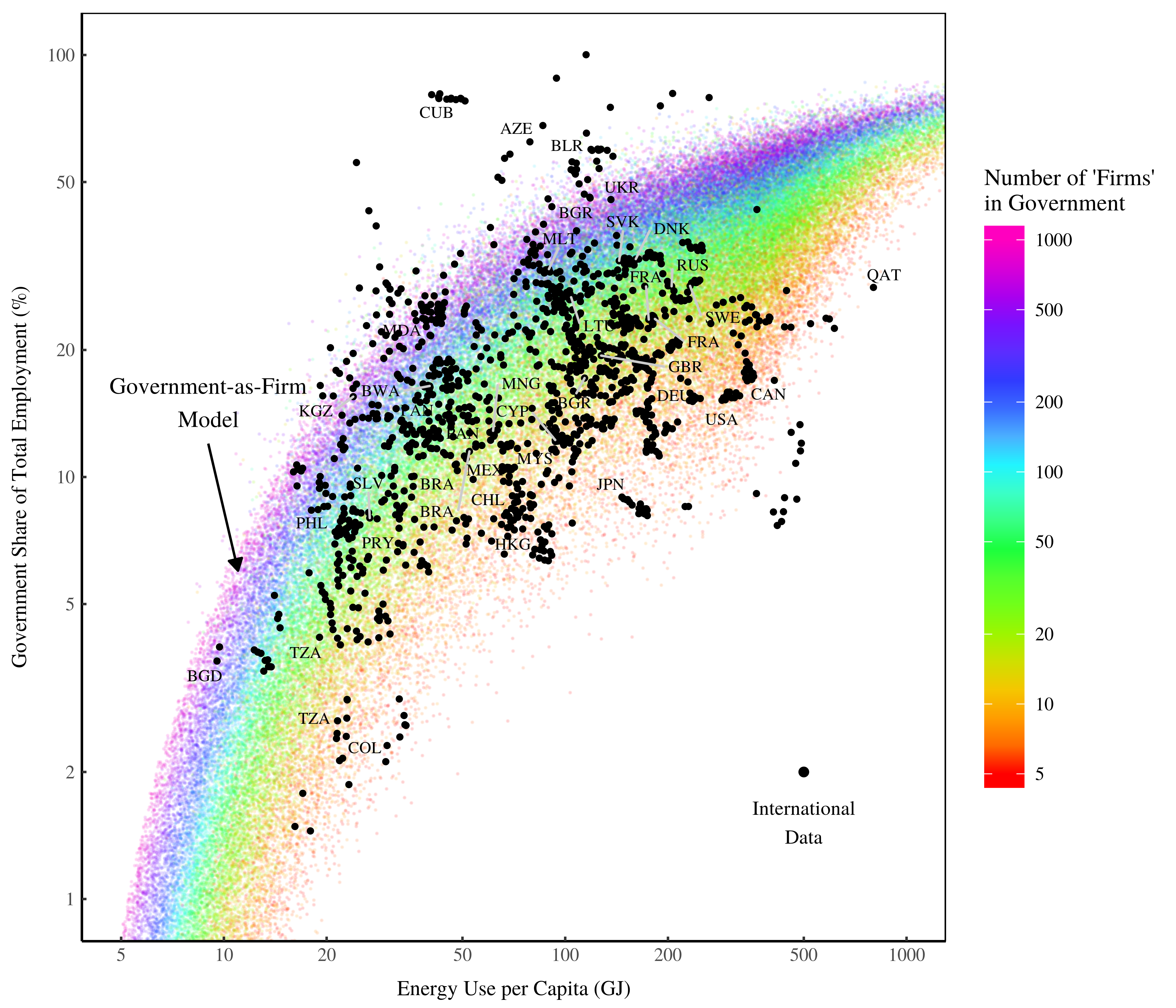

Figure 1 shows this trend. Here the vertical axis shows the government’s share of employment in a given country. The horizontal axis shows energy use per capita. Energy use serves as my measure of economic development. (I don’t use the standard measure of economic growth, real GDP, because it’s fatally flawed.) Each squiggly line represents the path through time of a country.

Figure 1: Government share of employment vs. energy use per capita. Lines represent the path through time of a country. I’ve labelled select countries with their three-digit code. Data for government employment comes from ILOSTAT series GOV_LVL_PSE (all public sector employees). Data for total employment and energy use come from the World Bank series SL.TLF.TOTL.IN and EG.USE.PCAP.KG.OE, respectively.

Looking at Figure 1, you can see that as energy use increases, governments get larger. So our neoclassical prediction — that government should get smaller with economic development — is wrong. Governments get bigger with economic development.

What about the political view of government? It appears to be partially true. Yes, economic growth correlates with government size — something that’s unexpected if politics alone shape the size of government. But that doesn’t mean there’s no role for politics.

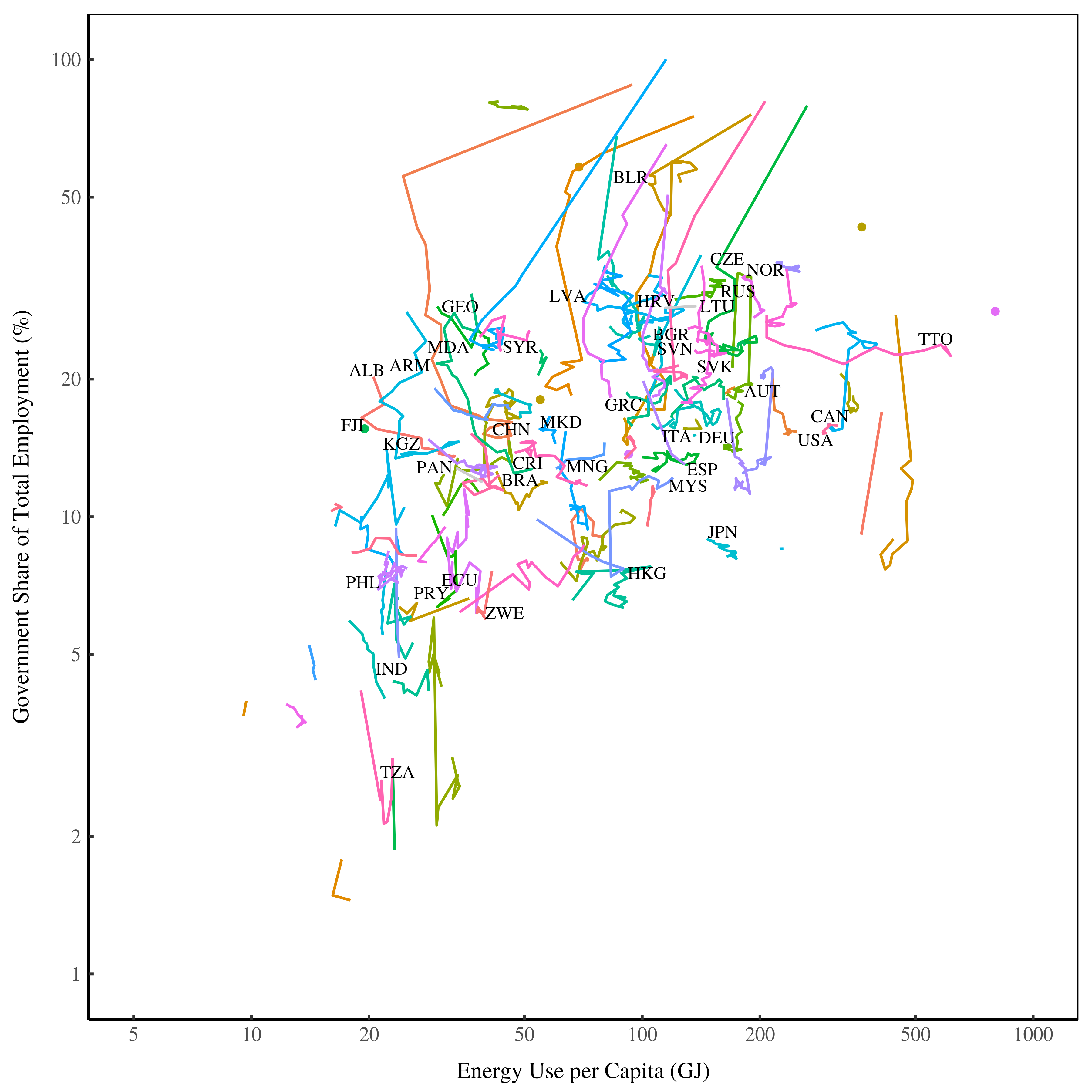

To see how politics affect government size, we’ll have another look at the data in Figure 1. This time we’ll distinguish between two types of countries:

- Those that have never had a communist government

- Those that have had (or still have) a communist government

Figure 2 shows this distinction. Unsurprisingly, communist countries tend to have larger governments than their non-communist counterparts.

Figure 2: Politics and government size. I distinguish here between countries that have had a communist government (red) and those that haven’t (blue). Lines represent the path through time of a specific country. I’ve labelled the (once) communist countries with their country codes. Communist status comes from this Wikipedia page.

Let’s pause, for a moment, and discuss the history that’s on display here. Figure 2 shows the collapse of the Soviet Union in action. The data begins in 1990, just as the Soviet Union crumbled. Newly liberated countries like Ukraine (UKR), Estonia (EST), and Maldova (MDA) appear in the data.

These former Soviet-block countries begin with nearly 100% government employment — a remnant of their communist past. But over the next decade, the governments in these countries shrank drastically. And as they did, energy use plummeted. You can watch this happen in Figure 2. Former Soviet states start at the top of the chart and then move down and to the left. Most other countries move up and to the right. History in action.

Back to our question. Do politics affect the size of government? The answer is yes. The evidence in Figure 2 proves the importance of politics. But this evidence also shows something unexpected. Government size increases with energy use independently of politics.

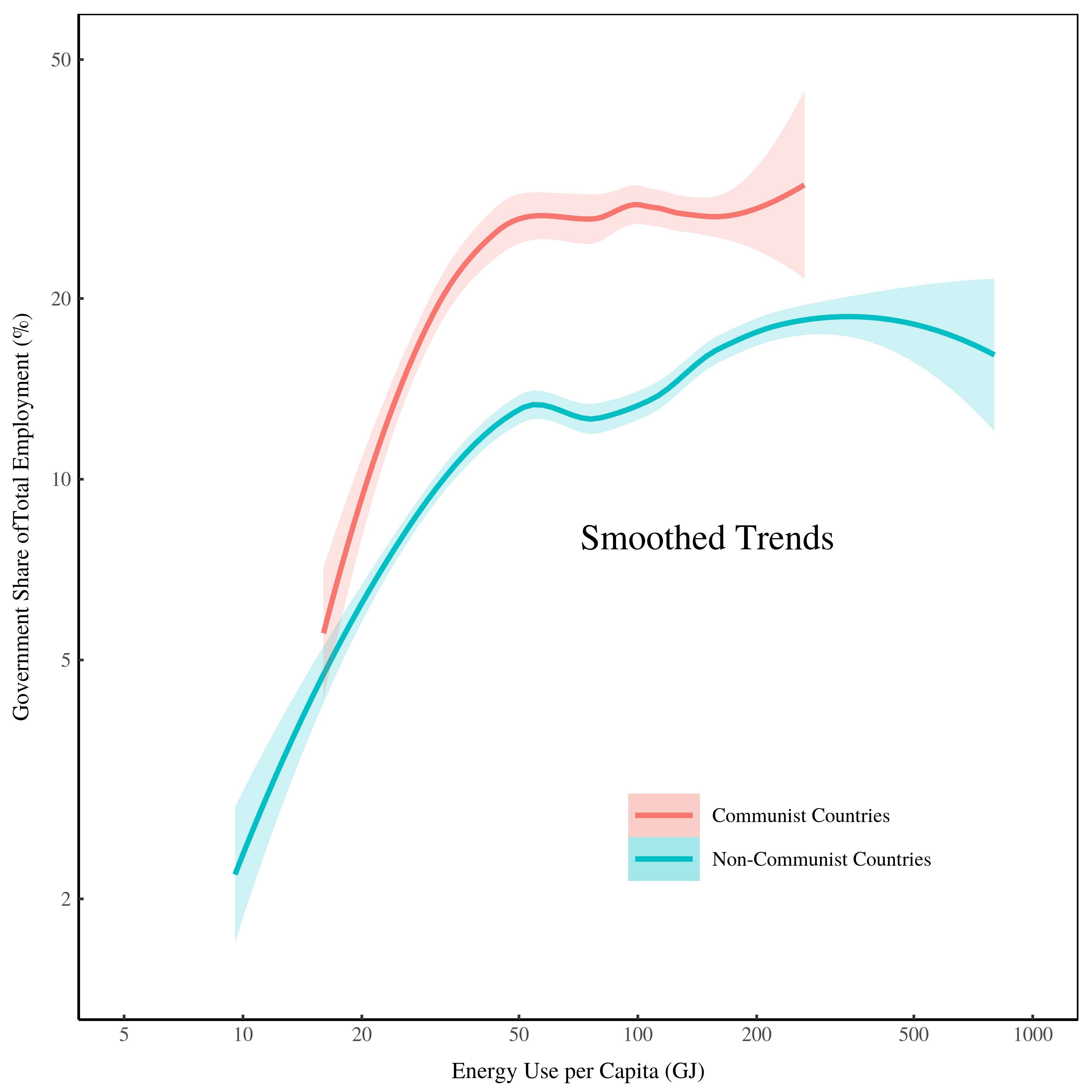

This fact isn’t easy to see in Figure 2. To make it clearer, I’ll smooth the trends between countries. Figure 2 plots the trend for communist countries and the trend for non-communist countries.

Figure 3: Trends in the size of government. Here I’ve taken the data from Figure 2 and plotted the smoothed trend within communist and non-communist countries. (For the math people, the trend is a locally estimated scatterplot smoothing of the raw data.)

What do you see in Figure 3? What I see is two versions of the same trend. In both communist and non-communist countries, governments get larger with economic development. I’m still marvelling at this result. It’s compelling evidence that something besides politics shapes government size. For some reason, the size of government is connected to energy use.

So what causes the trend? Why does government get larger with economic development? This is a difficult question to answer. But what we can say is that government is not alone. As energy use increases, all institutions get bigger.

Economic growth = bigger institutions

One of the exciting things about doing social science is discovering that your own family history fits into a bigger trend. My maternal grandparents were self-employed farmers. My parents are retired teachers who worked for a small school board. And me? I’m a PhD-trained political economist who hopes to someday work at a university.

What you see, in my family history, is tendency for each generation to work for a larger institution. You’ll probably find something similar in your own family history.

This trend towards bigger institutions, hinted at in family histories, is visible in more rigorous statistics. As Figure 4 shows, the average size of firms tends to grow with economic development.

Figure 4: Average firm size vs. energy use per capita Data for average firm size comes from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Data for energy use comes from the World Bank series EG.USE.PCAP.KG.OE.

So government isn’t alone in getting bigger with energy use. As societies develop, all institutions get bigger.

Does this trend help us explain the size of government? Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that placing something in a larger trend helps us model it. No, in the sense that observing a trend doesn’t explain why it exists.

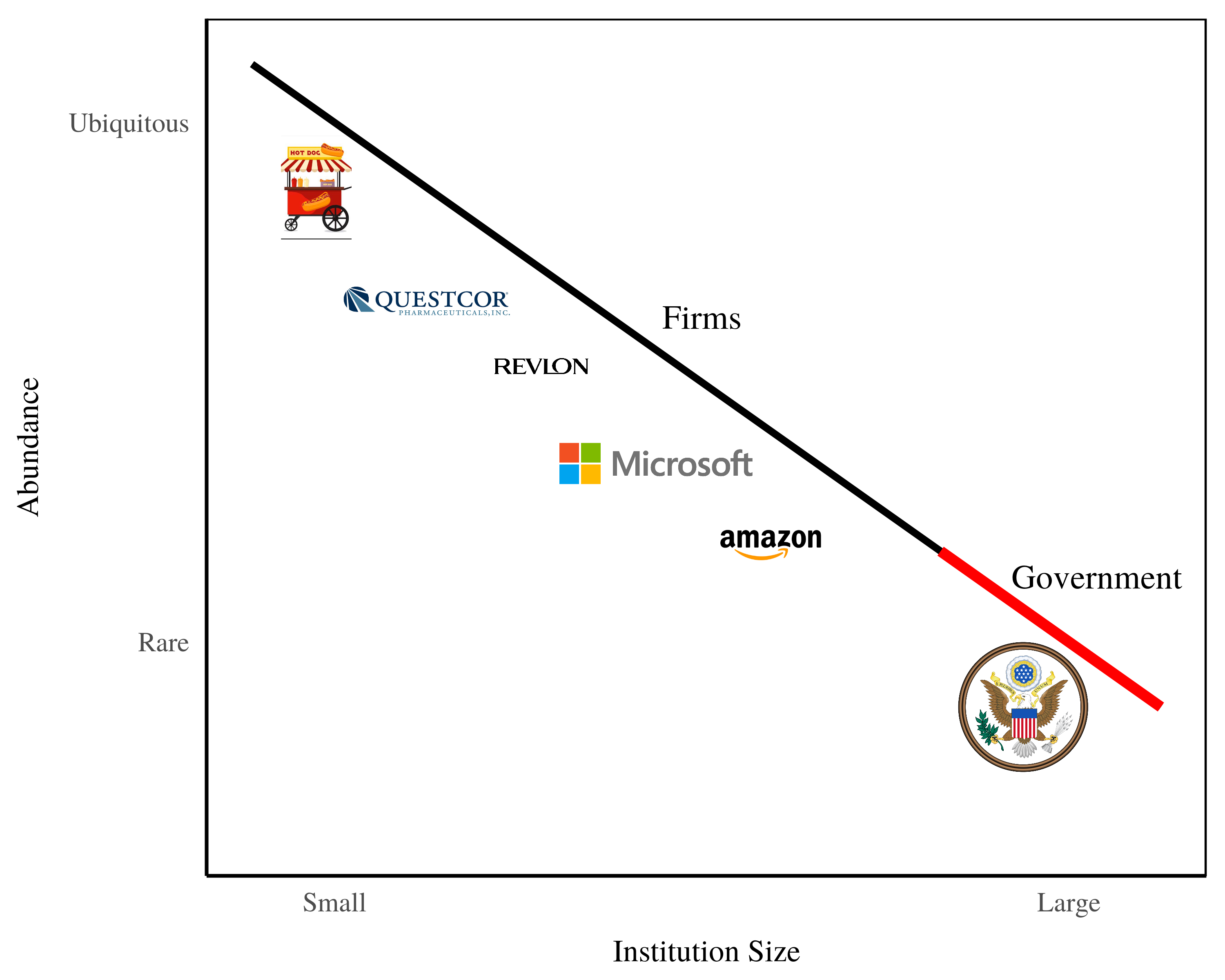

Let’s use animal abundance as an example. Across all life, there’s a trend between organism size and abundance (see Part 1). Small organisms are ubiquitous. Large organisms are rare. This trend allows us to predict the abundance of an organism from its size. But the trend doesn’t tell us why the organism has the abundance it does.

The same is true of government. Knowing that government is riding a larger trend doesn’t tell us why governments grow with economic development. But it helps us model this growth.

The government-as-firm model

Governments, I claim, are like whales.

Let me explain.

As the largest animals on Earth, whales are exquisitely different than other animals. Yet when it comes to predicting abundance, these differences don’t matter. Whales are ‘just another animal’. Their abundance is predictable from their size alone.

I propose that the same is true of governments. Because they’re the largest institutions, governments are exquisitely different than other institutions. Yet when it comes to predicting government abundance, I argue that these differences don’t matter. Governments are ‘just another firm’. Their abundance is predictable from their size alone.

Wordsmith that I am, I call this hypothesis the ‘government-as-firm’ model. Here’s what it looks like:

Figure 5: The government-as-firm model

In this model, we assume that human institutions become less abundant with size. Small institutions are ubiquitous. Large institutions are rare. Next, we imagine that most of these institutions are business firms. But above some size threshold, firms turn into ‘government’. In short we model government as the n largest firms.

Predicting the growth of government with energy use

On the face of it, the government-as-firm model has nothing to do with energy. Instead, it tells us how the size of government relates to the size of firms. But it’s easy to bring energy into the equation.

To do this, we first use the government-as-firm model to predict how government size grows with firm size:

average firm size ⟶ government size

Then we use the empirical trend in Figure 4 to predict how energy use grows with firm size:

average firm size ⟶ energy use

Lastly, we combine these two models. Presto! We can predict how government will grow with energy use. [1]

So let’s get to the predictions! Figure 5 shows the international trend between energy use and the size of government. The black points are the same data as plotted in Figure 1. (For clarity, I haven’t connected the points within each country.) Behind the real-world data, I show the predictions of the government-as-firm model. As you can see, the predictions are not bad.

Figure 6: The government-as-firm model vs. real-world evidence. Here I’ve plotted the empirical data from Figure 1 as black points. (For simplicity, I haven’t connected the dots between countries.) The colored points show the government-as-firm model. Color indicates the number of ‘firms’ in government, the model’s sole parameter.

What’s with the rainbow in Figure 5? Color shows the model’s sole parameter — the number of ‘firms’ in government. I’ve modelled government as the n largest firms. Since the number n is arbitrary, I let it vary. The rainbow in Figure 5 shows this variation.

I treat the number of ‘firms’ in government as a political preference. Here’s an example. In right-leaning societies, services like healthcare are provided by the private sector. So healthcare institutions are ‘firms’. But in left-leaning societies, the same services are provided by government. So healthcare ‘firms’ become healthcare ‘government’. The idea is that leaning left means adding ‘firms’ to government. And leaning right means taking ‘firms’ away from government.

With our model in hand, let’s reflect on the empirical evidence. First, we know that regardless of politics, governments get bigger as energy use increases. Second, politics shift this trend up or down. Communist politics shift the trend up, making governments larger. Free-market politics shift the trend down, making governments smaller (see Figure 2).

So what does our model say about these findings? Governments, the model suggests, get bigger with energy use because they’re riding a more general trend. All institutions get bigger as energy use increases. So in this respect, we can treat government as ‘just another firm’.

Politics then shift the energy-government trend up or down. Communist countries add firms to government, making government larger. Non-communist countries take firms away from government, making government smaller.

Whether we’re interested in (a) the bigger trend, or (b) how politics affects this trend depends on our world view. I’m a big-picture guy, so I like to focus on the bigger trend.

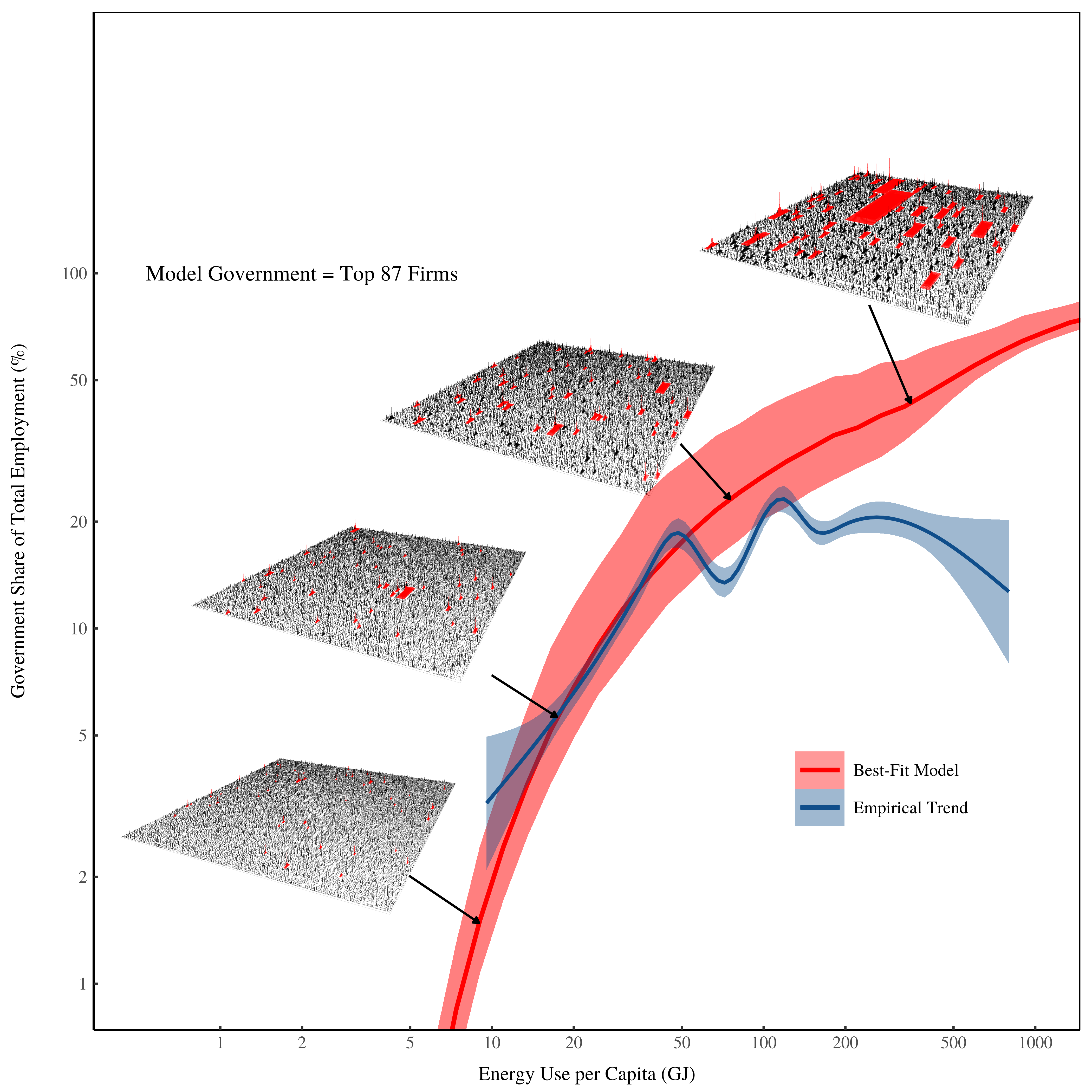

On that note, let’s look at the overall trend between government size and energy use. It’s the blue curve in Figure 7. Next to this real-world trend, I’ve plotted the best-fit government-as-firm model. In this model, government consists of the 87 largest ‘firms’. To get a sense for how the model works, I’ve added inset plots that illustrate the government-as-firm model as a landscape. Black pyramids are firms. Red pyramids are government. As energy use increases, firms tend to get larger. Government rides on top of this wave.

Figure 7: Government size vs. energy use — real-world and modeled trends. The blue line is the smoothed trend for the raw data plotted in Figure 1. The red line is the smoothed trend for the best-fit model (in which government consists of the top 87 firms). (For the math people, the trends are a locally estimated scatterplot smoothing of the raw data.) The inset plots illustrate the government-as-firm model as a landscape. Black pyramids are firms. Red pyramids are government.

Looking at Figure 7, you can see that the government-as-firm model isn’t perfect. It overshoots the real-world data for large energies. But discrepancies aside, it’s surprising that such a simple model can predict anything about government size.

Think of the complexity of human societies. Think of the vitriol of politics. Think of the endless debates about what government should do. Our model suggests that at the largest scales, none of this matters. As societies develop, governments behave like all other institutions. They get bigger.

Beyond politics

I’ll close on a philosophical note. It’s comforting to think that the size of government is determined largely by politics. It gives us a sense of agency. If we collectively want bigger (or smaller) government, we can have it!

The government-as-firm model rains on this parade. It suggests that politics, while important, are subservient to a larger trend. As societies develop, all institutions get larger. Government just rides this wave.

This idea is chilling because it constrains our agency. Sure, hunter-gatherers can try to create big governments. But the evidence suggests that they’ll fail. Conversely, industrial societies can try to shrink their government to the size typical in agrarian societies. But the evidence suggests that they’ll fail. As the Rolling Stones put it, “you can’t always get what you want.”

While this limit is chilling, in the grand scheme of things it’s not surprising. Look at the animal world. There are limits everywhere. Ants, for example, can’t evolve to be the size of elephants. Why? Because ants have a passive circulatory system that wouldn’t work when scaled to elephant size. Likewise, elephants can’t evolve to be the size of ants. Why? Because below a certain size, warm-blooded animals can’t maintain their body temperate. An ant-sized elephant would die of hypothermia. [2]

When we look at the biological world, then, we see limits everywhere. So it’s unsurprising that we find limits within human society. Our body has limits, and so do our institutions.

So why can’t undeveloped societies have large governments? Probably because if they tried, they’d starve. I’m not joking. Governments, as a rule, don’t farm. So their existence depends on farmers producing a surplus. If you try to build a big government on the backs of subsistence farmers, you have a problem. The farmers can feed themselves, or they can feed government bureaucrats. Either way, somebody starves (usually the peasants).

Framed this way, it’s unsurprising that the history of communism is tied to starvation. Think of Holodomor, the Ukrainian famine caused by Stalin. Think of the Great Chinese Famine caused by Mao. These famines occurred as communist governments aggressively expanded, but farming productivity didn’t keep up. And so peasants starved.

It’s easy to understand why undeveloped societies can’t have big governments. But why can’t developed societies have small governments? This is harder to answer. My own view is that we need larger institutions to cope with growing complexity. But Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler have a very different view that’s worth reading.

Regardless of why governments grow with economic development, we have a simple model that can explain how this happens. Assume that government is ‘just another firm’.

Notes

[1] Details of the government-as-firm model. I model the size distribution of firms with a power-law. I then simulate the growth of firms by lowering the power-law exponent. In the model, ‘government’ consists of the n largest firms. I predict energy use per capita by plugging the model’s average firm size into the regression on real-world data shown in Figure 4.

[2] As warm-blooded animals, elephants need to keep their bodies above the ambient temperature. But below a certain size, they can’t do this. Why? Because heat loss is proportional to surface area, while the ability to generate heat is proportional to volume (mass actually, but mass scales with volume). Thanks to a quirk of geometry, the ratio of surface area to volume explodes as objects shrink. This means that heat loss grows relative to heat generation. So below some critical size, warm-blooded mammals can no longer maintain their body temperature. For more details see:

Ahlborn, B. (2005). Thermodynamic Limits of Body Dimension of Warm Blooded Animals. Journal of Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics, 25(1), pp. 87-102

Further reading

Energy and Institution Size. PLOS ONE. 2017; 12(2):e0171823.