Home › Forum › Political Economy › ההון ושברו (Capital and its Crisis)

- This topic has 21 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated December 23, 2022 at 4:30 am by Rowan Pryor.

-

CreatorTopic

-

November 25, 2022 at 3:57 pm #248619

Exciting to see there is an upcoming book from Jonathan and Shimshon. https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/752/

The obvious comment would be that an English translation would be nice, but these things take time — if it happens, it happens. So I wonder, Jonathan, are there English proxies for what this book will cover?

- This topic was modified 3 years, 2 months ago by jmc.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

November 25, 2022 at 6:27 pm #248620

Thank you, James. The 602-page doorstopper is on its way to the bookstores, though, for some reason, the publisher’s book page isn’t up yet.

The book presents and situates CasP theory and research — our own as well as that of others — within the broader evolution of political economy. Some of this material has already appeared in English, but much of it hasn’t, so a translation would be nice. Whether we will do it is another matter….

- This reply was modified 3 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

November 30, 2022 at 10:21 pm #248627

I’ve already asked Jonathan (and/or Shimshon) some very silly questions on their Twitter. After I got a good, succinct answer, I posted this Twitter reply.

“Yes, my questions were mostly wrong-headed. I still don’t get CasP properly even though I have read the (original “Capital as Power”) book and key papers. It’s like I am “firm-wared” to think of everything as related to prices and not related to other things. And I never even studied economics formally.

This “firm-wareing” of thought patterns is really, really difficult to overcome. I strongly take the point that prices do not reflect value but rather instantiate power relations. And yet I (still) expect the capitalist book-keeping to add up. So I keep advancing questions that assume that (price) values in the different categories and “departments” (in the Marxian sense) will add up and make arithmetic accounting sense through the economy. Yet there is no reason why they should (add up) under conditions of capricious money creation and money destruction.”

I like to hope that occasionally in questioning others and myself I come up with potentially valid ideas. At the moment I am clinging to this idea of “capricious money creation and capricious money destruction” in contemporary capitalism as accounting for the bifurcation of stock prices and goods & services prices. If money can be capriciously created and destroyed (and it can be and is) then while the arbitrary national accounting identities can be maintained as mathematical identity equations, the bifurcation of stock prices and goods and services can proceed apace and untethered each to each by prices or “value prices”. There would seem to be no necessary relation of prices in that sphere: at least not one governed by national accounts or economic category and department accounts.

Again, I could be off-track here. There is one little bit of CasP I get (understand) because it relates to my ontological investigations of real systems and formal systems/notional systems. The rest of CasP I clearly still don’t get because of my enculterated firm-ware biases. One has to unlearn conventional economics even when has not learnt it formally. Its paradigm is so insidious.

-

December 2, 2022 at 9:30 pm #248640

This “firm-wareing” of thought patterns is really, really difficult to overcome. I strongly take the point that prices do not reflect value but rather instantiate power relations. And yet I (still) expect the capitalist book-keeping to add up. So I keep advancing questions that assume that (price) values in the different categories and “departments” (in the Marxian sense) will add up and make arithmetic accounting sense through the economy. Yet there is no reason why they should (add up) under conditions of capricious money creation and money destruction.”

Rowan,

The arithmetic operation you seek is division, not addition. CasP writings obscure this fact by discussing the addition of mark-up to costs to explain the pricing of commodities, but if you choose to model the pricing of all commodities and capital assets as discounting to risk-adjusted present value, which is both reasonable and straightforward to do (I did it on this forum recently), then profits are just the expected value (and reward) for embracing the risk the capitalist discounted previously.

There’s no surplus. There’s no exploitation. There’s no sabotage. There’s just the allocation of risk through discounting, aka “capitalization.” At least that is what the neo-neo-classical economists may say in another 40 years or so, when they realize CasP is an opportunity, not a threat, and incorporate it into their new nonsensical theology. Of course, they won’t say capital is power. They’ll just use the parts of CasP that are useful and jettison the parts that are cryptic (e.g., “power is confidence in obedience”). A better way to say “power is confidence in obedience” that would make it harder for today’s neo-classical “priests” to embrace and suppress CasP is “power is confidence in setting the discount rate,” or, more simply “power is the ability to set the discount rate.”

-

December 3, 2022 at 7:41 pm #248642

“power is confidence in setting the discount rate,” or, more simply “power is the ability to set the discount rate.”

1. I think we need to distinguish between individuals and groups who determine the discount rates they apply when trying to price expected future earnings (me, Elon Musk, JPMorgan Chase) and the average discount rate prevailing in society. If we take the individual perspective, my power is the same as Musk’s and JPMC, since all of us are free to set our own discount rates as we see fit. If we take the average perspective, then there is no singular entity or group to associate this power with, since the average discount rate is determined by the shifting structures of capitalism.

2. By saying that power is simply ‘the ability to set the discount rate’, you seem to imply that the power of any given entity — me, Musk, JPMorgan Chase — is independent of its (expected) profit. Do you really mean that?

-

December 3, 2022 at 8:35 pm #248643

Scot,

Come on mate, give me a break. When someone says “it doesn’t add up” that is a colloquial expression. When dealing with arithmetic or math, the potential for any and all operators to be involved is not literally excluded. 😉 But I guess you were just joking.

I’m not sure why my point on ““capricious money creation and capricious money destruction” has not been picked up on. Is it “too MMT” or “too Chartalist”? The point is money is fictitious, nominal, formal (choose your preferred term). Obviously, money can be created ex nihilo and destroyed ab nihilo. One thing we need to do (IMHO) is look at the capitalist capture of money creation and money destruction. I don’t think this detracts from CasP but necessarily adds to it. Of course it’s a corporate cartel of powerful capitalists who have captured the formerly state apparatus of money creation and money destruction, not any individual capitalist. When a system runs on chits, it helps to be part of the cartel which prints and shreds the chits, selectively. Or am I wrong? Tell me where I am wrong.

-

December 3, 2022 at 9:40 pm #248644

2. By saying that power is simply ‘the ability to set the discount rate’, you seem to imply that the power of any given entity — me, Musk, JPMorgan Chase — is independent of its (expected) profit. Do you really mean that?

I think I am saying is the opposite.

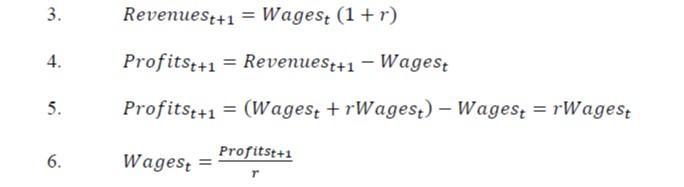

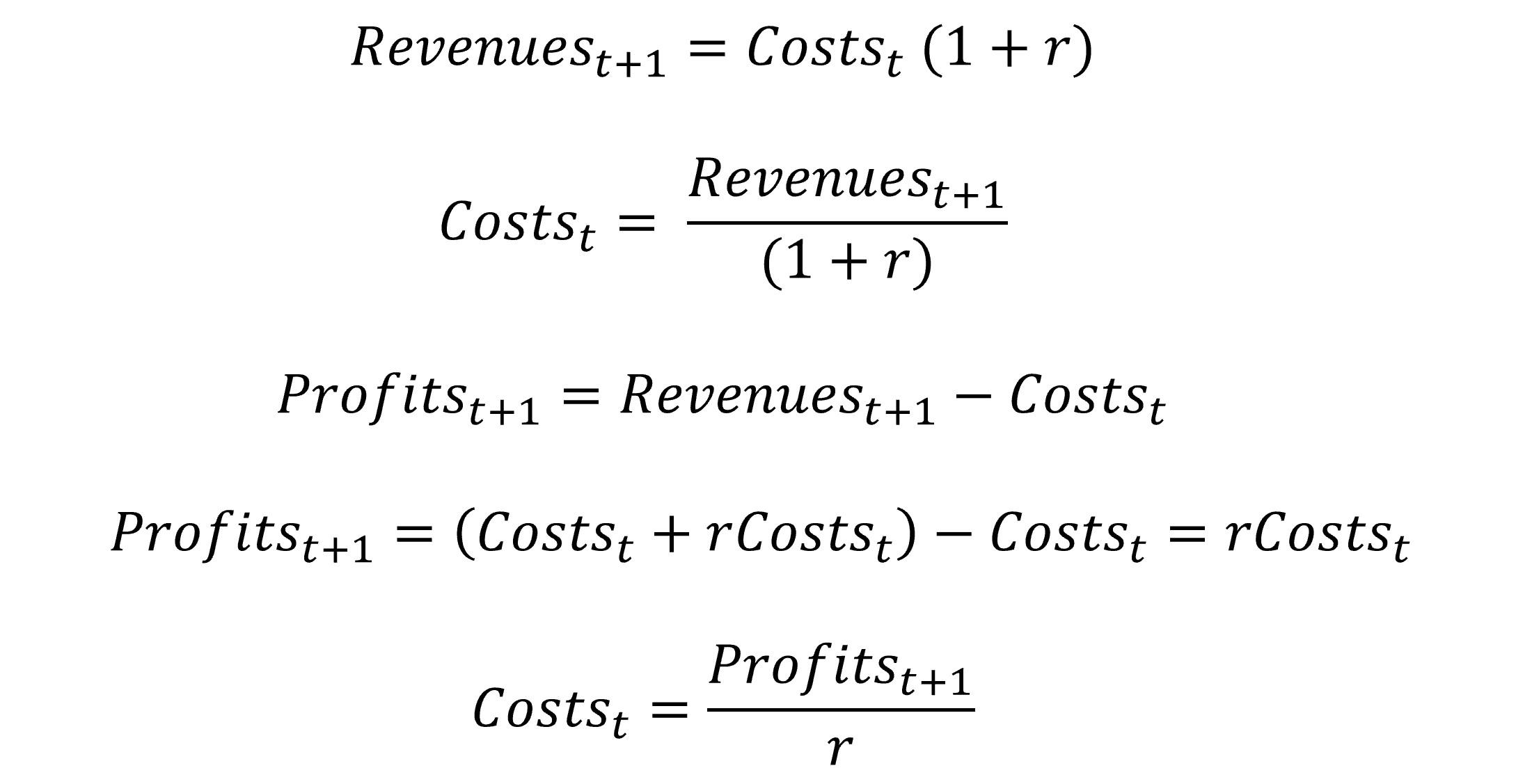

In a world where the capitalist uses the capitalization equation to set what it will pay for input costs such as wages by discounting its expected profits from future sales, the discount rate used by the capitalist determines (and ensures) the capitalist’s profits. See equation 6, below.

In this sense, profits can be viewed as a “risk premium” accruing to the benefit of the capitalist for (1) providing liquidity to labor, eliminating labor’s risk of survival, while (2) taking on the risk of failing to make a sale. To accept the wages the capitalist offers is to accept the capitalist’s discount rate and provides all the evidence of obedience the capitalist needs to assure its power.

Regarding your first point, I understand and agree that we must distinguish between discount rates set by individual capitalists and the average discount rate of capitalists writ large. I mean, that distinction is the basis for differential accumulation and differential power, right? But is there any reason we cannot apply the insight that wages are just discounted profits in this macro, “average” sense? For example, if wages are just discounted expected future profits, then average hourly wages are necessarily correlated to corporate profits and, by extension, to the SP500 Index, and your Power Index, which is taken from the average/macro level, seems to prove that.

-

December 4, 2022 at 9:49 am #248646

In a world where the capitalist uses the capitalization equation to set what it will pay for input costs such as wages by discounting its expected profits from future sales, the discount rate used by the capitalist determines (and ensures) the capitalist’s profits. See equation 6, below.

Scot,

That’s a clever way of presenting your point, but I don’t think the point itself is correct.

1. What capitalists agree to pay workers certainly depends on their profit expectations, but this dependency is not what your equations express.

2. The discount rate is what investors use to capitalize expected future profits. In your equations, though, r is not the discount rate (the rate of growth of capitalization), but the profit markup over costs (assuming all costs can be expressed as wages).

3. Moreover, the way you express it, r reflects not the intended markup, but the realized one.

4. The realized markup – and therefore actual future profit — is neither at the capitalist’s discretion nor knowable beforehand. It depends on how much capitalists will be able to sell in the future, which is anybody’s guess (and the reason why profit forecasters are almost always wrong).

5. Since capitalists don’t know their actual future profit, they cannot set current wages as a function of that profit.

6. By definition, the wage bill is the product of the wage rate and the level of employment. In general, capitalists control the level of employment — but, in my view, they don’t set the wage rate, which is the result of historical conditions and an ongoing, complex power conflict within the firm and across society. Expected (though not actual) future profit is merely one element of this conflict.

7. For Kalecki, the markup reflects capitalist power. But this reflection is ex post, not ex ante. The discount rate, by contrast, is set ex ante, not ex post. I think it is erroneous to treat them as if they were the same.

8. Perhaps it will be useful to try to express your equations in ex-ante terms (rather than ex post), using the discount rate (rather than the markup).

- This reply was modified 3 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

December 3, 2022 at 9:54 pm #248645

Scot, Come on mate, give me a break. When someone says “it doesn’t add up” that is a colloquial expression. When dealing with arithmetic or math, the potential for any and all operators to be involved is not literally excluded.

But I guess you were just joking. I’m not sure why my point on ““capricious money creation and capricious money destruction” has not been picked up on. Is it “too MMT” or “too Chartalist”? The point is money is fictitious, nominal, formal (choose your preferred term). Obviously, money can be created ex nihilo and destroyed ab nihilo. One thing we need to do (IMHO) is look at the capitalist capture of money creation and money destruction. I don’t think this detracts from CasP but necessarily adds to it. Of course it’s a corporate cartel of powerful capitalists who have captured the formerly state apparatus of money creation and money destruction, not any individual capitalist. When a system runs on chits, it helps to be part of the cartel which prints and shreds the chits, selectively. Or am I wrong? Tell me where I am wrong.

Rowan,

That was more of a riff than a joke, and I certainly did not mean it at your expense. I think CasP on its own terms requires reconsidering the relationship between wages and profits in view of the capitalization equation, which equilibrates the value of one thing at two points in time through multiplication/division, not addition/subtraction.

While modern money is endogenous, it is not fictitious. If it were fictitious, there would be no homelessness, no poverty, etc. The reason money is not fictitious is because human institutions exist to make the consequences of not having money very real. Tim Di Muzio has done the most work on integrating endogenous money theory with CasP analysis. See his Debt as Power, An Anthropology of Money, and The Tragedy of Human Development.

I would also argue that the MMT/neo-chartalist history of money is flat wrong (although certain insights are true). See Colin Drumm’s thesis (I can provide a link). His online courses on money are fascinating and provide a lot of interesting sources throughout history (including Greek tragedies and Shakespeare’s plays).

-

December 4, 2022 at 5:58 pm #248655

In a world where the capitalist uses the capitalization equation to set what it will pay for input costs such as wages by discounting its expected profits from future sales, the discount rate used by the capitalist determines (and ensures) the capitalist’s profits. See equation 6, below.

Scot, That’s a clever way of presenting your point, but I don’t think the point itself is correct. 1. What capitalists agree to pay workers certainly depends on their profit expectations, but this dependency is not what your equations express.

Jonathan,

Thanks for the comments, which are very helpful. Let me see if I can clarify things, in part by making some things explicit that may not have been.

My equation 6 is ex ante, just like the capitalization equation at page 154 of Capital as Power (2009), and flows from my past experience in setting annual budgets for firms. So, just as capitalists agree to pay for a share of a firm’s stock based on expectations of future earnings, firms budget for input costs (e.g., wages) based on expectations of future profits. I explicitly argue this in my original comment deriving equation 6:

Equation 6 is the same form as the capitalization formula (5) found at the bottom of page 154 of Capital as Power (2009). Thus, wages paid to labor today can be viewed properly as the “risk-adjusted discounted value of expected future earnings” (i.e., Profitst+1), i.e., wages can be viewed as the capitalization of expected profits (or power, if you would prefer). As you’ve said, “capitalization represents the present value of a future stream of earnings: it tells us how much a capitalist would be prepared to pay now to receive a flow of money later.” Capital as Power, at p. 153.

While I agree that firms don’t explicitly employ the discounting formula or a discount rate as part of their annual budgeting process, inherently (mathematically) they do, if they use target mark-ups or profit margins (most capitalist firms use both in some way). That’s what my derivation of equation 6 was intended to show.

2. The discount rate is what investors use to capitalize expected future profits. In your equations, though, r is not the discount rate (the rate of growth of capitalization), but the profit markup over costs (assuming all costs can be expressed as wages).

Actually, the discount rate is a feature of discounting wherever and however applied. There is no single discount rate for everything at every level of the capitalist system, but every instance of discounting has a corresponding discount rate. Thus, the discount rate of a loan extended to a firm can be different than the discount rate the firm applies to expected profits to budget costs (including wages), which in turn can be different than the discount rate capitalists apply to the firm’s expected future earnings. If discounting is used to price money, wages, and equities, the capitalist system is basically a fractal as each level of the system (money, labor, equities) is “self-similar” to the other because each uses discounting to set prices to accumulate power.

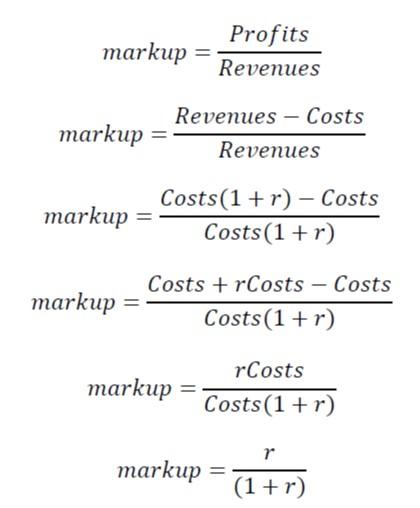

Also, the formula for markup is r/(1+r), not 1/r:

3. Moreover, the way you express it, r reflects not the intended markup, but the realized one.

Actually, my intention was to express expected profits, not realized profits, and I said so in my original comment deriving equation 6, as shown above. If we say “expected” instead of “intended,” the same is true of the way you express r in equation 5 at the bottom of page 154 of Capital as Power (2009). Does the future often prove that such expectations were unwarranted? Sure, but that doesn’t make using discounting any less useful for planning/pricing.

The point of discounting is to commensurate two values of the same thing separated in time. The only value we actually ever know is the the present value. The future value is always speculative, which is okay because firms can reduce spending (the present value ) if it appears the future value will fall short of expectations, and they can do so in a manner that adjusts the effective discount rate to make up for missing prior expectations.

Again, budgeting does not explicitly apply discounting, but if the budget includes expectations of profits, it inherently uses discounting.

4. The realized markup – and therefore actual future profit — is neither at the capitalist’s discretion nor knowable beforehand. It depends on how much capitalists will be able to sell in the future, which is anybody’s guess (and the reason why profit forecasters are almost always wrong).

Again, this is true of the capitalization equation at page 154 of Capital as Power (2009). A key difference between capitalization and annual budgeting is that firms plan one fiscal year at a time. It is much easier for firms to forecast revenues/profits accurately on an annual basis than it is for capitalists to price equities into infinity. Also, a firm has the ability to control its expenses, while investors in the firm do not have the ability to control the firm’s earnings.

I recognize that your capitalization equation is somewhat simplified and idealized, but, however expressed, the market capitalization of a firm as calculated by using the last sale price of shares is never accepted by capitalists as an accurate statement of the firm’s value. If that were the case, no shares would transact (every sale of stock is the seller shorting the stock and the buyer going long). This is why financial analysts use things like discounted cash flow analysis to assess what they believe is the actual “intrinsic” share price of a firm.

5. Since capitalists don’t know their actual future profit, they cannot set current wages as a function of that profit.

Nobody knows the future, which is why everybody sets prices (or budgets expenses, or sets a share price objective) based on expectations. Banks make loans knowing there is a risk of default. Firms set annual budgets based on expected profits knowing there is a risk they will not be able to meet expectations. Financial analysts set price objectives using current expectations of future earnings knowing the firm may not meet future expectations.

Anyway, firms set budgets to constrain expenses, including payrolls. If profit targets seem unlikely to be met, the firm can reduce its workforce through layoffs to achieve the desired discount rate (or markup, which is determined by the discount rate).

6. By definition, the wage bill is the product of the wage rate and the level of employment. In general, capitalists control the level of employment — but, in my view, they don’t set the wage rate, which is the result of historical conditions and an ongoing, complex power conflict within the firm and across society. Expected (though not actual) future profit is merely one element of this conflict.

Okay, but each firm determines how large its payroll is. Make of it what you will.

7. For Kalecki, the markup reflects capitalist power. But this reflection is ex post, not ex ante. The discount rate, by contrast, is set ex ante, not ex post. I think it is erroneous to treat them as if they were the same.

During the annual budgeting process, the discount rate and the markup are both set ex ante. That’s just the nature of the budgeting process, the relationship between profits and costs, and the math of discounting. Given an expected markup of m, you can determine the expected discount rate r, even if the concept of “discount rate” and the discounting formula are never explicitly used in the budgeting process.

8. Perhaps it will be useful to try to express your equations in ex-ante terms (rather than ex post), using the discount rate (rather than the markup).

The discounting formula is always ex ante because the future value at time t+1 is not known but expected. Since my equation 6 distinguishes between time t (the present) and time t+1 (the future), I think the suggested work has already been done.

Am I still missing something? The best critique I can see of what I’ve tried to do is that CasP’s capitalization equation is based on a number of simplifying assumptions that I don’t have to make, and the actual math of applying discounted cash flow analysis to determine the intrinsic value of a firm is much more complicated and messy than we are discussing. That’s okay to me because it is enough to be “self-similar,” if the iterative use of discounting over time and space results in capitalism being fractal in nature (which I think it does). Capitalism’s “mega-machine” may just be a self-replicating “nano-bot” called discounting.

Before I finish, we should circle back to the concept that discounting commensurates (equilibrates, really) two values or prices, separated in time, both for the same object. I think this is really important, but I have not had the chance to think through the implications except for how it implies the logic of capitalism is fractal, which may explain why it seems to be so totalizing.

-

December 4, 2022 at 6:07 pm #248656

A related thought:

Just as the future value of something is unknowable, so, too, is the risk. Perhaps the discount rate is really a reflection of relative power and not risk, at least when it comes to certain instances of discounting?

-

December 4, 2022 at 8:49 pm #248657

Scot,

I think the issue here is not only whether we can write the equations correctly (which often we don’t), but also – and perhaps more so — whether the equations justify our conclusions.

You write that:

In a world where the capitalist uses the capitalization equation to set what it will pay for input costs such as wages by discounting its expected profits from future sales, the discount rate used by the capitalist determines (and ensures) the capitalist’s profits.

I think this interpretation is fundamentally wrong.

In and of themselves, capitalist expectations of profit, the ex-ante discount rate used to concoct these expectations, and the impact these expectations have on how much they spend on inputs, do not and cannot determine, let alone ensure, actual profits.

It seems to me that your claim here is not only unrealistic, but also self-contradictory.

Imagine every potential capitalist expecting his/her own profit into existence. This mana-from-heaven magic will make everyone an instant, insatiated capitalist, bring their individual expectations into conflict with each other, and pretty much ascertain that their actual profits will differ from what they expect.

In my view, discounted values do not generate power. Instead, it is power that generates discounted values.

But we can agree to disagree.

-

-

December 4, 2022 at 9:28 pm #248658

Scot, I think the issue here is not only whether we can write the equations correctly (which often we don’t), but also – and perhaps more so — whether the equations justify our conclusions. You write that:

In a world where the capitalist uses the capitalization equation to set what it will pay for input costs such as wages by discounting its expected profits from future sales, the discount rate used by the capitalist determines (and ensures) the capitalist’s profits.

I think this interpretation is fundamentally wrong. In and of themselves, capitalist expectations of profit, the ex-ante discount rate used to concoct these expectations, and the impact these expectations have on how much they spend on inputs, do not and cannot determine, let alone ensure, actual profits. It seems to me that your claim here is not only unrealistic, but also self-contradictory. Imagine every potential capitalist expecting his/her own profit into existence. This mana-from-heaven magic will make everyone an instant, insatiated capitalist, bring their individual expectations into conflict with each other, and pretty much ascertain that their actual profits will differ from what they expect. In my view, discounted values do not generate power. Instead, it is power that generates discounted values. But we can agree to disagree.

Jonathan,

If you read what I wrote today here and here, you will see I have already back-tracked on my earlier language from yesterday, which you quote above. I have made it clear that equation 6 is an ex ante calculation of forecasted profits, not actual profits, and everything I’ve written previously other than the language you quote supports my claim about the ex ante nature of the calculation, which is clear from the context of its derivation. Hence, my quoted, ill-advised statement regarding “ensuring” actual profits is no longer operative, and you should consider it retracted.

Therefore, please take the time to address what I said here, almost twenty hours after I wrote the language you quote and three hours before you wrote the response quoted above.

If there remains any disagreement, it is not about this: discounted values are determined by discount rates, and discount rates reflect relative power. To me, as I said before, this implies power is confidence in setting the discount rate of a transaction, or, more simply, power is the ability to set the discount rate in the one’s favor. I view either statement as equivalent to confidence in obedience.

What I believe I have shown is that, if I pay you money today in return for your promise of the future payment to me of that same amount of money plus a premium, we can express the relationship between today’s payment and the future premium as discounting. This is true whether today’s payment is provided as a loan, as wages, or as the purchase price of shares, and whether the future premium is in the form of interest, profits, or earnings per share (profits per share less depreciation, amortization and income tax). The future payment of the premium is never guaranteed, but that does not prevent “pricing” what I pay you today by discounting the expected premium you will pay me in the future.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 2 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: removed extraneous language

-

December 5, 2022 at 4:12 pm #248664

Scot,

Apologies if I misinterpreted your intention. The truth is that I read your long reply to my 8 points, but found myself lost in its details. I also didn’t see an explicit retraction of you original argument that capitalists determine their profit — but, again, there are many moving parts in your reply, so maybe I didn’t understand it properly.

Instead of answering each of your individual points, let me try to digress our view and suggest how it might differ from yours (as I understand it).

Capitalization is given by:

1. K = expected future earnings / discount rate

The right-hand side of this expression can be decomposed into to 4 elementary particles

2. K = (future earnings * hype) / (normal rate of return * risk)

Power-driven capitalists try to augment their differential capitalization (marked by the .d extension) (Note that, because the normal rate is common, its differential value normalizes to 1 and drops from the equation.):

3. K.d = (future earnings.d * hype.d) / risk.d

***

POINT 1. When Eq. 3 is applied to a capitalized entity or group of entities, every element in it represents a distinct aspect of the power of that entity: the future earnings it will receive relative to those of the benchmark, the hype it can create relative to the benchmark, and the risk it can keep low relative to the benchmark, all contribute to its overall capitalized power relative to the benchmark.

From this viewpoint, the differential discount rate (which reduces to differential risk in this formulation) is distinct from differential future earnings and differential hype and therefore has to be treated as only one aspect of power. This conclusion differs from your notion, as I understand it, that, because pricing supposedly relies on discounting, all power can be reduced to the discount rate.

POINT 2. In our view, none of these elementary particles is set exclusively by the entity owners themselves. Instead, these particles are determined by the power conflicts in which the entity is embedded and on which it acts. Thus, differential future earnings, even if greatly influenced by the differential power of the entity, are meaningful only as a conflictual relation with the power of other entities and processes who boost/reduce it (including workers, governments, customers, criminals, culture, wars, etc.). Similarly with differential hype and differential risk, which the entity can alter in one direction but others can change in another.

The result is that capitalized power — which we understand as the quantitative differential representation of many qualitatively different conflicts — is not a top-down dictate of the powerful, but an ever-changing culmination of an ongoing conflict that spans society at large. Capitalists and the entities they own are at the top of the capitalized hierarchy, but their position in that hierarchy as well as the very structure of that hierarchy are constantly changing because power always invites and is exercised against opposition (Ulf Martin’s autocatalytic sprwal).

POINT 3. These considerations might serve to explain why CasP puts so much emphasis on theoretically informed empirical research. Without such research, we cannot decipher — and simplify — the complex trajectories of differential capitalization nor understand the underlying qualitatively different processes that drive those trajectories. Without this deciphering and understanding, our equations and theories remain empty shells at best and misleading corps at worst.

-

December 5, 2022 at 5:11 pm #248665

Scot,

If I understand you correctly, you use r to denote the discount rate, which is distinct from the markup, representing the ratio of profits/revenues.

To me, the discount rate r denotes the rate of return (i.e., the rate at which the entity’s assets grow).

- Do you share this view? If you do, why is your following expression valid: revenues = Cost (1 + r)

- If you don’t share this view, what do you mean by the discount rate?

-

December 19, 2022 at 10:34 pm #248756

Scot, If I understand you correctly, you use r to denote the discount rate, which is distinct from the markup, representing the ratio of profits/revenues. To me, the discount rate r denotes the rate of return (i.e., the rate at which the entity’s assets grow).

Scot, If I understand you correctly, you use r to denote the discount rate, which is distinct from the markup, representing the ratio of profits/revenues. To me, the discount rate r denotes the rate of return (i.e., the rate at which the entity’s assets grow).- Do you share this view? If you do, why is your following expression valid: revenues = Cost (1 + r)

- If you don’t share this view, what do you mean by the discount rate?

Jonathan,

Sorry for the delay in responding.

I view r as both the rate of return (e.g., interest rate) and the discount rate. They must be the same. That’s what makes discounting and compounding inverse, reversible functions of one other: they share the same value of r.

Since profits equal rCosts, revenues must equal Costs(1 + r) such that they yield rCosts after netting out Costs.

-

December 20, 2022 at 6:22 am #248760

Thank you Scot.

I think we are talking past each other. Accountants distinguish between capital invested and the rate of return on the one hand, and the cost of items sold and the markup on the other, such that:

1. rate of return = profit / capital

so: profit = rate of return * capital

2. markup = profit / cost of items sold

so: profit = markup * cost of item sold.

***

In your notes, you say that:

3. profit = rate of return * cost of items sold

Unless I made a mistake somewhere, for this last equation to be true, cost of items sold = capital, which normally isn’t the case.

-

December 20, 2022 at 5:26 pm #248761

Thank you Scot. I think we are talking past each other. Accountants distinguish between capital invested and the rate of return on the one hand, and the cost of items sold and the markup on the other, such that: 1. rate of return = profit / capital so: profit = rate of return * capital 2. markup = profit / cost of items sold so: profit = markup * cost of item sold. *** In your notes, you say that:

3. profit = rate of return * cost of items sold Unless I made a mistake somewhere, for this last equation to be true, cost of items sold = capital, which normally isn’t the case.

PROFIT AND RATE OF RETURN

I don’t think there is any real disagreement here.

Remember, all I was trying to do was determine whether wages (as a proxy for all input costs) can be viewed as being priced as the discounting of future profits , and they can be. Importantly, my simplified example was limited to a single period (e.g., a fiscal year) in which all capital outlays at the beginning of the period are recouped at the end of the period from the sale of those products along with the profits. So, in my simplified example, capital and costs (or wages, if they are the only costs) are the same thing (addressing your last point).

Yes, things get more complex if we start differentiating between costs that are capitalized expenses (via depreciation) and those that are simple wages, but the discounting never goes away, and that is what matters.

While this insight allows us to view the pricing of the costs incurred by a business as being similar to the pricing of shares of stock for that business, that does not mean they are the same. Not all discounting is capitalization, and I would argue that discounting within a single period, as I’ve done in my simplified model, is not capitalization, which requires discounting into perpetuity, not over a single period. Also, the capital outlays of a business are not the same as the capital outlays of shareholder in that business. The business and its shareholders are investing their capital in different things, at different times, in different markets, over different time periods, all interconnected by a chain of discounting operations assuming different rates of return.

MARKUP

My markup equation is correct.

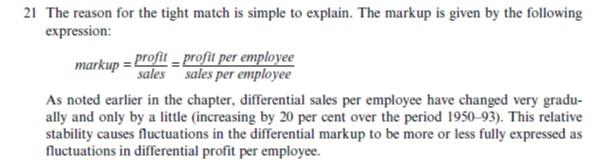

According to Blair here, markup = profit/sales. (He asserts profit = sales x markup; divide both sides by sales, and you get my equivalent expression).

In Capital as Power (2009), you explicitly define markup as profit/sales. See Fig. 16.3 on page 373 and associated discussion, especially footnote 21 on page 373:

To be fair, in your discussion profit is computed after depreciation, amortization, and income taxes, but my example assumed none of those things applied. Either way, markup = r/(1+r).

Unrelatedly, there seems to be an error in footnote 20 on page 241 of Capital as Power (2009). To achieve a target return of 20%, you need a markup of 16.67%, not 10% (markup equals r/(1+r)), and 16.67% is what you get when you divide $200M in profit by $1.2B in sales (2/12 = 1/6 = 16.67%) on an initial investment of $1.0B.

-

December 20, 2022 at 7:23 pm #248762

Thank you Scot.

Perhaps you mentioned it somewhere in the thread, but it is only now that I realize you define revenues = sold capital + sold output. Since this definition is rarely if ever used either in practice or in accounting pedagogy, I won’t be surprised if others were perplexed by your derivations as I was.

Unrelatedly, there seems to be an error in footnote 20 on page 241 of Capital as Power (2009). To achieve a target return of 20%, you need a markup of 16.67%, not 10% (markup equals r/(1+r)), and 16.67% is what you get when you divide $200M in profit by $1.2B in sales (2/12 = 1/6 = 16.67%) on an initial investment of $1.0B.

Yes, there is a mistake here, but not the one you refer to.

I don’t have the book by Kaplan et al. with me, but if I recall correctly, they define the markup = profit/cost. Our mistake was to use their definition in the footnote without noting it was different than the one we used in the text. In any event, thank you for pointing it out.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

December 20, 2022 at 7:25 pm #248763

PROFIT AND RATE OF RETURN

…

Not all discounting is capitalization, and I would argue that discounting within a single period, as I’ve done in my simplified model, is not capitalization, which requires discounting into perpetuity, not over a single period. Also, the capital outlays of a business are not the same as the capital outlays of shareholder in that business. The business and its shareholders are investing their capital in different things, at different times, in different markets, over different time periods, all interconnected by a chain of discounting operations assuming different rates of return.

Scot,

1. I have been trying to follow this discussion as closely as I can. I am a bit confused about how r functions in all of this argument. The general argument is that capitalists are discounting inputs with a future expectation of profit. But if different processes — which you say are not always capitalization, but discounting — how can they all use one value of r in the same point of time? If I’m following, the desire for a unified theory is also allowing for r to be anything, according to situation — the r in a forward-looking budget is not necessarily the r in capitalization. So why do they need to be both r?

2. Is there an issue of “revealed preferences” if wages are discounted future expectations? Unless we have independent confirmation of r before wages are paid, are we not left with wage cost + an implied discount, but which we don’t know?

- This reply was modified 3 years, 1 month ago by jmc.

-

December 20, 2022 at 11:58 pm #248766

Scot, 1. I have been trying to follow this discussion as closely as I can. I am a bit confused about how r functions in all of this argument. The general argument is that capitalists are discounting inputs with a future expectation of profit. But if different processes — which you say are not always capitalization, but discounting — how can they all use one value of r in the same point of time? If I’m following, the desire for a unified theory is also allowing for r to be anything, according to situation — the r in a forward-looking budget is not necessarily the r in capitalization. So why do they need to be both r? 2. Is there an issue of “revealed preferences” if wages are discounted future expectations? Unless we have independent confirmation of r before wages are paid, are we not left with wage cost + an implied discount, but which we don’t know?

James,

I am sorry if I have been as clear as mud. I am putting something together that I hope will clear things up (or prove that I am just plain wrong). In the meantime, here are some short-ish answers to your two questions.

1. There is no “one r to rule them all.”

The rate of return r is different for each discounting operation in a chain of discount operations, e.g.,

debt/credit money creation (bank, term of the loan) –> profit generation (firm, annual) –> market capitalization (investor, in perpetuity).

Every link in the chain applies its own discounting at its own rate of return (discount rate) r to ensure that, on paper and according to the formula (whether using compounding or discounting), the entity extending capital today gets back more capital in the future at the desired rate of return over the relevant term. Because these discounting operations are chained together, they necessarily affect each other, especially if expectations are not met, e.g., debt service related to a loan is considered in the profit generation and market capitalization links, affecting the discount rate applied differently.

NOTE: CasP’s discounting equation sacrifices detail for clarity and does not reflect how investors and analysts actually build free cash flow models to predict future earnings and the appropriate discount rate (which is usually the weighted average cost of capital, or WACC, of the firm being modeled). If everybody assumed or agreed that the present market capitalization is accurate, which the simplified equation 5 sort of implies, nobody would trade shares. Trading requires a disagreement in valuation, which creates a spread. Thus, every buyer goes long, and every seller goes short, at least relative to each other. I don’t think this reality makes the simplified equation 5 any less valid. In fact, I think it is a very powerful approach to teaching a fundamental truth.

2. At every link of the chain, there is no (and can be no) ex ante, independent confirmation that the extension of capital today will result in the expected and/or contracted rate of return in the future, not even in the case of a loan secured by collateral. Nevertheless, the logic of discounting is applied at each link of the chain, even if, in some cases, we habitually think of things like profits as involving addition of an arbitrary amount (or absconding with “surplus” labor) instead of compounding or discounting because we do not consider the passage of time, which accounting hides from view by commensurating past expenditures with present revenues and profits.

Basically, all I am arguing is that if you recognize input costs as being incurred before revenues and profits are received, it is appropriate to view input costs (including wages) as discounted revenues or profits, which occur later in time, where revenues are discounted by (1+r) and profits are discounted by r.

Again, for all intents and purposes, costs are capital outlays within the period of interest, regardless if “capital” remains on the balance sheets. Once you recognize capital expense on the income statement, it comes off the balance sheet.

-

December 23, 2022 at 4:30 am #248780

Capital and its Crisis.

“Don’t worry. Everything is out of control.” – The Tao.

The same crisis over and over?

https://aeon.co/essays/are-plagues-and-wars-the-only-ways-to-reduce-inequality

As Thomas Piketty discovered from his research: “If r>g then inequality increases.” If rate of return on capital exceeds the economic growth rate then inequality increases. Theoretically, we can increase growth rate and/or decrease return on capital to change the equation. As the article notes; wars, plagues, famines and revolutions have been the main ways throughout history that r and g have been changed in the equalizing directions. One thought this suggests is that capitalism is not as sui generis as its theorists claim.

Both Pro-capitalist and Marxist theorists implicitly claim that capitalism is special: that it alone releases the revolutionary productive forces which have transformed the world. The capitalist sees this as an endless progress to private wealth utopia. The Marxist sees it as sweeping away all old systems and then unleashing the next stage of history where socialism will inevitably (somehow) triumph. Models of more persistent, more fundamental forces in human societies (per Walter Scheidel and thinkers like Peter Turchin) show a different picture. What are these more persistent, more fundamental forces in human societies or rather forming human societies and driving them? They have to be the “nature of nature” and the nature of man. The first sounds tautological, the second sounds essentialist.

The “nature of nature” is simply the natural forces we confront, which are fundamental and unchangeable by humans. The nature of man also consists of material and corporeal fundamentals which we cannot change by will or choice. It seems, if history shows these long patterns, under discussion in the linked essay, then these fundamental forces are more determinative than we would wish: as we do wish in all our fond humanist teleological theories where the progress or direction of history occurs according to our goal choices (this according to us of course).

More random thoughts.

It’s interesting, and perhaps diagnostic, that conventional economics talks about hedonics but not about eudaimonics. It talks about utility and disutility but not about purpose, fulfillment or meaning. Inflation theory is attempted with hedonic adjustments but not with eudaimonic adjustments. Wages, goods and services are all utility (supposedly) and work is all disutility (supposedly).

Conventional economics talks about efficiency, efficient use of resources, and trashes the biosphere and humans unsustainably. That is hardly efficient.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 1 month ago by Rowan Pryor.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 1 month ago by Rowan Pryor. Reason: More random thoughts

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.