Home › Forum › Political Economy › Capital as Power in the 21st Century: A Conversation

- This topic has 12 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated March 14, 2025 at 8:30 pm by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

CreatorTopic

-

March 1, 2025 at 1:55 pm #250214

On December 3, 2024, Michael Hudson met with capital-as-power researchers Jonathan Nitzan, Tim Di Muzio and Blair Fix to discuss the intersections between their two lines of research.

The video recording of the discussion is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tBOU4xBg2pA (or click the image above)

The full transcript is here: https://capitalaspower.com/2025/02/capital-as-power-in-the-21st-century/

- This topic was modified 11 months, 3 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

March 6, 2025 at 7:27 pm #250230

Well, a nice opportunity to engage with a researcher who carries a good reputation and considerable popularity (at least on the fringe of political economy discourse). And I appreciate the comradely discussion. But as the talk progressed I felt a growing sense of frustration. The potential was there for a meaningful engagement, but it did not materialize, in my opinion. Hudson was generally satisfied with pointing out apparent similarities, when anything of value actually lies in examining the differences of the two approaches more closely.

It made me think of dozens of conversations (with political partners, friends, sympathizers) I have had over the years, about the usefulness and necessity of a (new) power theory of capitalism. Unlike debates with orthodox Marxists, and similar to the one with Hudson, the faultlines were not situated at the heart of theories of value but at the boundaries of each. Later on, I’ll try to find the time to explain what I mean by that. For now I’ll just say this conversation is useful for identifying some practical hurdles CasP is facing, in appealing as an alternative framework for political praxis. So, it’s worth our attention, even though it doesn’t provide a lucid theoretical engagement.

-

March 6, 2025 at 10:10 pm #250231

I look forward to your take on the conversation and the hurdles for CasP it points to.

-

-

March 8, 2025 at 8:38 am #250232

Michael Hudson: “…But instead of using the general term ‘power’, I wanted to be very specific and focus on the term economic ‘rent’ as distinguished from ‘value’, as the unearned element; as was just described, the capitalization of corporate wealth over and above the actual value, cost value. (The book value of the tangible wealth — the socially necessary labor costs, ultimately, necessary to create the means of production.)”

This is the most substantial theoretical claim I could track down in what Hudson said. At face value, it points to a plain adherence to some labor theory of value, at the core at least. But it’s totally secondary. When Jonathan claims the distinction between productive and unproductive entities is meaningless, Hudson skates through the problem by saying something like – nowadays, all industrial capital is “infected” by capitalization, so sure, I can go along with that (I’m paraphrasing into lingua CasPa). So it’s not the categorization of different entities which is at the heart of disagreement. It is the apparent radical difference between book value and financial value, and their qualitatively different meanings.

A different line of argument from a CasP perspective could emphasize commodities in general, pointing out that book value is just historical value recorded, dependent on prices which are themselves the product of capitalization at a specific time (a machine worth is determined by discounting expected future earnings associated with control of the machine in a certain production setup). So all “cost value” is already “financial”, in a way. And if we can convince this is the case, then there is no radical difference between those categories of prices.

Now, the gist of the matter lies here. I would argue the inability of heterodox scholars to engage with CasP is not rooted in adherence to different theories of value. I’m thinking here about Keen, Varoufakis, Hudson and the likes (mostly post-Keynesians and neo-Marxists). They are not dependent on a quantitatively meaningful “real” theory or quantities. Implicitly, I think they accept it’s all about power, but they regard the power associated with controlling production directly (as supposedly manifested through cost value) as “good”. But good in what way? I don’t think it’s mainly based on morals, as Blair indicated. It’s based on functionality: The rational power-based order of production under capitalism (we could agree it’s more rational than the centrally planned economy of the USSR, right?). It functions in reproducing social order and sustain needs, and that is considered good (at least as a starting point, politically).

The rest is rent, finance, crises, bubbles, etc. Not the bubbles of the real/nominal divide, but the ones emerging from the mismatch of different rational orders. After all, the nominal sphere of capitalist production is grounded in real bio-physical quantities, or at least, it must take them into account when operating as a quantitative ordering of society. Prices are all nomos, yes, but it’s not the detached, parasitic and often delusional nomos of finance. Of course, capitalist production shouldn’t be autonomous. It should be directed, for example, to take into account the ecological crises. It’s not a perfect rational system, but it’s a whole other beast than finance.

Responding with fundamental critiques of neoclassical or Marxist value theories is not really effective in this context. So a reorientation of exposition and argument might be required if we to facilitate more fruitful engagements.

- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by max gr.

-

March 9, 2025 at 1:34 pm #250234

Responding with fundamental critiques of neoclassical or Marxist value theories is not really effective in this context. So a reorientation of exposition and argument might be required if we to facilitate more fruitful engagements.

So far, our exposition — namely, a critique of existing neoclassical and Marxist frameworks and findings + an articulation of CasP’s own framework and research — seems to have resonated with young, free-spirited researchers (like yourself) and to have elicited more or less dead silence from established political economists.

So something in our exposition (and substance) speaks to one group while deterring another, and I wonder how you and others think this exposition can be ‘reoriented’ to make engagements more fruitful without diluting CasP’s contents.

- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

March 12, 2025 at 7:03 am #250238

Tia and I have some thoughts on the matter, and we’ll try to articulate them soon.

But first, can you please explain what did you mean by saying:

“Second, if you drill a little deeper into the concepts of these two entities, you realize that real capital is backward-looking. It depends on the reinvestment of past profits, whereas market capitalization, which is emphasized by capitalists as well as CasP, is entirely forward-looking. It depends not on the bygone past, but on expectations about the unknown future.”

This seems to contrast with your exposition in רווחי מלחמה (I’m not sure if you wrote it in English as well), when you used the example of an oil tanker to speak about the actual nature of capital goods as forward looking capitalized items, recorded historically on the balance sheet.

-

March 12, 2025 at 10:33 am #250239

If I understand you correctly, your question concerns the difference between ‘real capital’ and ‘book value’.

REAL CAPITAL is an economic concept, denominated in universal units of either neoclassical utils or Marxist SNALT (socially necessary abstract labour time). The utils/SNALT presumably contained in any real capital were generated/produced in the past. Economists claim they can measure real capital, but as we explain in Chapter 8 of Capital as Power (2009), their measurement is entirely arbitrary if not circular.

BOOK VALUE is an accounting concept, denominated in dollars and cents. Usually, it denotes the money price of the asset at the time of its purchase. In Capital as Power (pp. 255-256) we note that book value represents the asset’s forward-looking capitalization at the time of its acquisition (the oil-tanker example). This feature means that, unlike the fluctuating market capitalization on the stock and bond markets, once set, book value no longer changes.

Are these two concepts related? Perhaps — but only in a perfectly competitive equilibrium with a perfectly known future (+ other assumptions that eliminate all resemblance to any known society).

- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

March 12, 2025 at 1:29 pm #250242

OK, so following on the above qoute from Hudson (which seems to suggest he is dependent on book value to represent “cost value”) — it would be valid to rephrase one of your subsequent paragraphs into:

“…the real capital stock, which political economists see as the beginning and end of capitalism, has nothing to do with (tangible) book value, which is the sole god of heterodox, anti-finance, economists.”

- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by max gr.

-

March 12, 2025 at 4:58 pm #250244

“…the real capital stock, which political economists see as the beginning and end of capitalism, has nothing to do with (tangible) book value, which is the sole god of heterodox, anti-finance, economists.”

While this statement may be theoretically correct, it is NOT what we want to say.

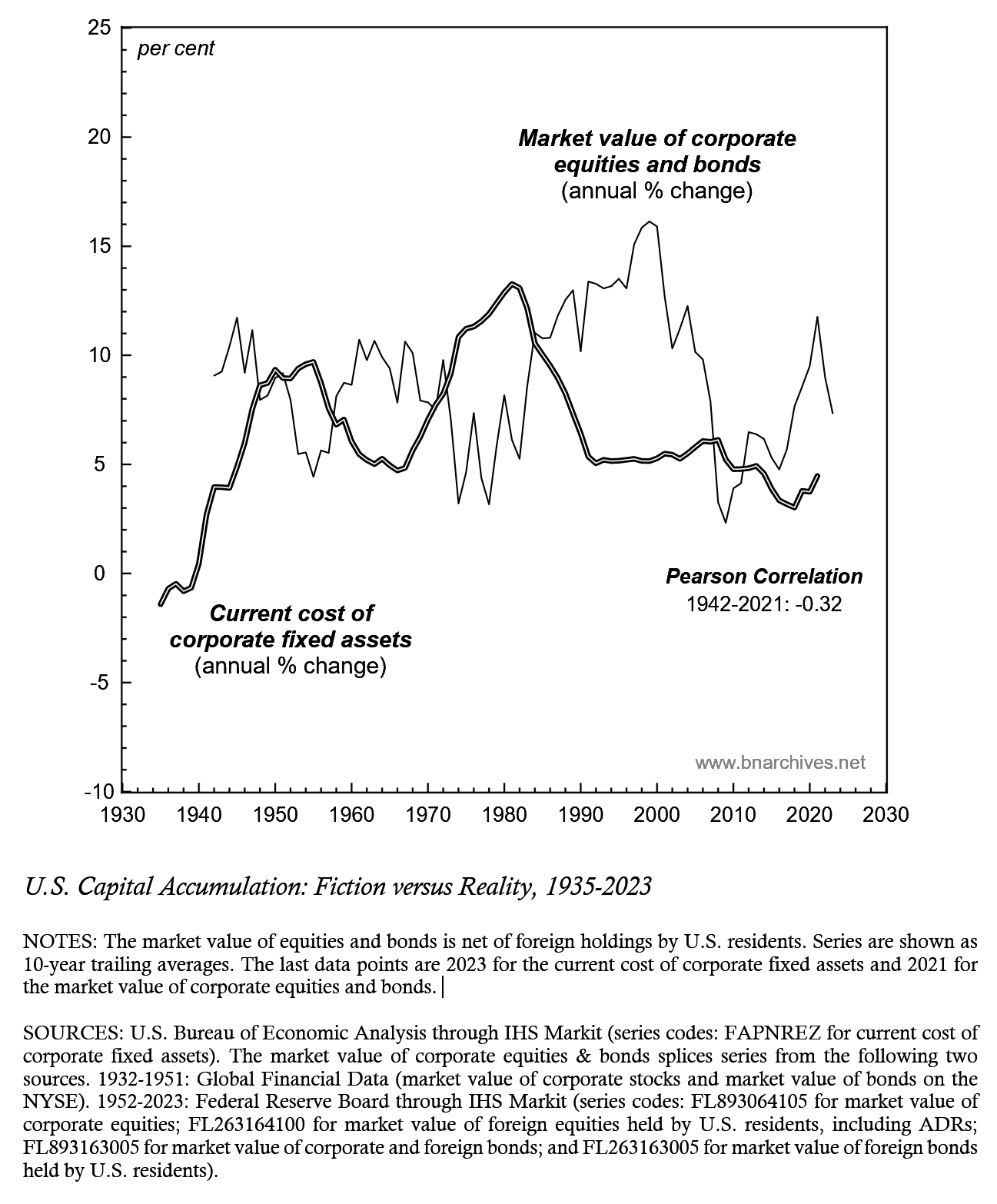

Our point, rather, is that forward-looking capitalization and backward-looking real capital are de-linked (and in the U.S. case inversely correlated, as the figure below shows).

I think that Hudson’s reference to ‘book value’ here is misleading; as I indicated above, book value represents forward-looking capitalization at the point of its recording and therefore includes rent which Hudson wishes to exclude…. From his vantage point, it would be more accurate to talk of ‘real capital’, and specifically, of the direct + indirect ‘labour cost’ of producing it.

I think that Hudson’s reference to ‘book value’ here is misleading; as I indicated above, book value represents forward-looking capitalization at the point of its recording and therefore includes rent which Hudson wishes to exclude…. From his vantage point, it would be more accurate to talk of ‘real capital’, and specifically, of the direct + indirect ‘labour cost’ of producing it.- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

March 12, 2025 at 6:46 pm #250246

While this statement may be theoretically correct, it is NOT what we want to say.

I understand the point as it is an important part of an ordered presentation directed for the general audience. But what I’m trying to think here is the inability to elicit a meaningful response from established heterodoxians, based on the current exposition. They (honestly, I believe) can’t see in it any worthwhile theoretical contribution, or at least it’s “nothing new”. This is not to say the general exposition should change, but maybe there are some tactical choices, different emphases to make, which might have an impact in this regard. Tentatively, I think it can be done by going after their presumably safe accounting reality (as opposed to “the financial fiction”). If some of the critique would be reoriented in this fashion, it might be harder to conclude out of hand that “our narratives are identical” (“forward-looking capitalization and backward-looking real capital [read: tangible book value] are de-linked? of course they are! We said it all along!”).

I think that Hudson’s reference to ‘book value’ here is misleading

Maybe so, but I doubt he will choose the more “accurate” way, based on real abstract/metaphysical units. I’m pretty sure the other heterodoxians I mentioned before will not go down that path. And for good reasons. So they stay explicitly anchored in accounting reality, even though that reality is not theoretically grounded (for them) in any value theory. That’s the starting point of the engagement, as I see it.

Our point, rather, is that forward-looking capitalization and backward-looking real capital are de-linked (and in the U.S. case inversely correlated, as the figure below shows).

And in this context, what the above analysis shows for the heterodoxians, has little to do with “real capital”. It shows the relationship between capitalization and tangible book value (this time in replacement rather than historical cost). When discussed in those terms, can we say anything about the reasons for the inverse correlation?

- This reply was modified 11 months, 2 weeks ago by max gr.

-

-

March 13, 2025 at 8:49 pm #250248

Thank you for the thoughtful comments, Max. Here are three observations.

1. Our figure uses replacement cost because, in principle, this is what national-account statisticians use to impute the ‘real capital stock’ (= replacement cost / price index of investment goods). In other words, when economic researchers – be they NC or heterodox – use the ‘real capital stock’, they use not its utils or SNALT content, but the capitalized price of ‘capital goods’, corrected, or so they believe, for price changes. And since this ‘real’ measurement template applies not only to capital goods, but to all commodities, it follows that value theories are not only conceptually circular/arbitrary but also lack an objective measure to quantify the ‘real economy’ they theorize.

2. Why does the replacement cost of the capital stock oscillate inversely with corporate capitalization? Although we haven’t researched this question, one possible answer is the co-movement of inflation and interest rates, which tends to have a positive effect on the replacement cost of the capital stock and a negative impact on corporate capitalization.

3. You suggest that established heterodox political economists are busy analyzing the ‘distortions’ of finance and other extra-economic ills and are unaware of or indifferent to the fact that they do not have a consistent theory of value to stand on. I agree – but, based on our long experience, I don’t think this is a trap we can easily trick or lure them out of. We are likely to be better received by younger thinkers — though even here, the window of opportunity tends to close rather quickly.

-

March 14, 2025 at 8:15 am #250249

which tends to have a positive effect on the replacement cost of the capital stock and a negative impact on corporate capitalization.

An empirical rather than analytical observation, right? Since, in principle, inflation can have the same positive effect on the value of different kinds of assets (through an increase in expected future profits); and the rate of interest is universal in its effect on capitalization.

Does a possible explanation lie in differential risk, as corporate capitalization is more susceptible to the heightened “risk environment” of high inflation rates?

Or maybe a simpler (connected) explanation: capital stock pricing is influenced more by debt, and an increase in the price of debt (interest) is transferred to the price of capital stock commodities by its sellers.

-

March 14, 2025 at 8:30 pm #250250

An empirical rather than analytical observation, right?

I think a bit of both.

1. Replacement cost is based on prices of newly produced capital goods. Unlike the prices of existing capital goods, which reflect the changing capitalization of their risk-adjusted expected earnings, among other factors, those of new capital goods are commonly ‘administered’ by their producers in line with normal cost and desired markup. During times of inflation and high interest rates, these administered prices tend to rise.

2. Market capitalization is affected by inflation positively (mainly by boosting expected profit in the numerator), as well as negatively (by increasing the discount rate in the denominator). However, the capitalization formula suggests that the latter (-ve) impact will usually outweigh the former (+ve) impact. For example, all else remaining the same, a 5% increase in expected future profit due to 5% increase in prices, accompanied by a 5 percentage points increase in the discount rate from 3% to 8%, will reduce capitalization by roughly 60%.

Obviously, these are partial back-of-the envelope arguments that invite further research….

-

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.