Home › Forum › Political Economy › Capitalists: Incapacitating Industry or Allocating Resources?

- This topic has 12 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated February 10, 2022 at 11:04 am by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

CreatorTopic

-

February 6, 2022 at 5:01 pm #247736

Are there negative consequences associated with unbridled industry? For example, over consumption of resources to the detriment of the natural resources or over-allocation of resources towards production of certain goods? If this is not the case then that would suggest that price mechanisms aren’t sufficient to indicate which resources maximise utility in an economy. If price mechanisms do fail to do so, are there any resources which explain the source of this failure?

Thanks!

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

February 6, 2022 at 8:50 pm #247737

rk374:

It depends on what we mean by ‘industry’.

1. If we understand industry in the spirit of Veblen — say, as denoting the ‘reasoned application of knowledge, human effort and material resources for the betterment of human and planetary life’ — then industry cannot systematically undermine these goals while retaining a definition that says the very opposite…. In this sense, industry cannot be ‘unbridled’.

2. This claim, though, applies only at a very abstract level. In practice, humans disagree on (1) what constitutes the betterment of human and planetary life, and (2) how the application of knowledge, effort and resources affects human and planetary life. So at this practical level, industry can become ‘unbridled’ to a greater or lesser extent, even in a society committed to these goals.

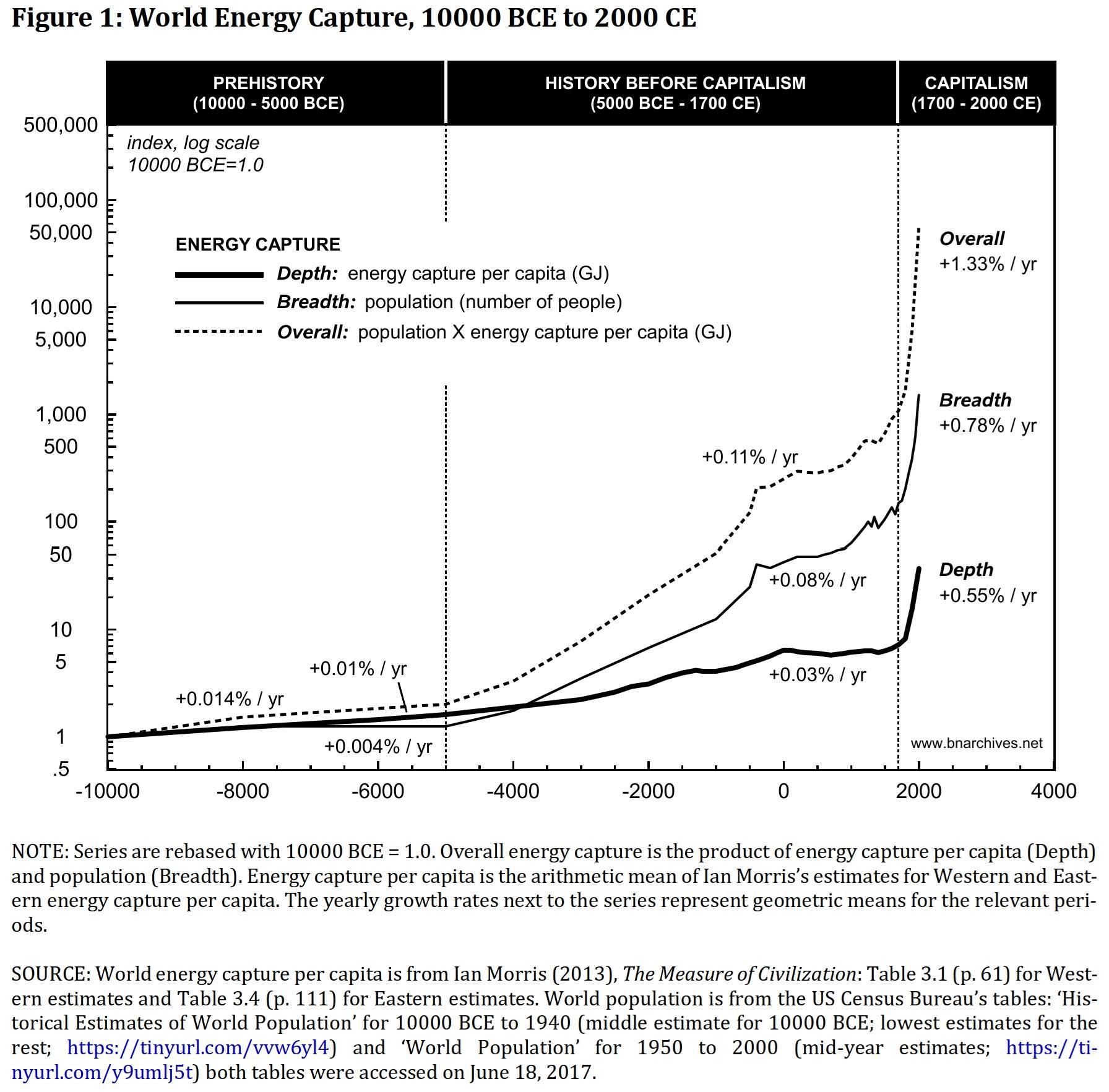

3. But we live in capitalism, and capitalism is driven by business not industry. Following Veblen and Mumford, our CasP theory argues that business undermines industry — i.e., it undermines the ‘reasoned application of knowledge, effort and resources for the betterment of human and planetary life’. But it does not undermine the use of knowledge, effort and resources as such. In fact, as the energy chart below shows, it augments it a great deal. The thing is that, in our view, this augmentation is not directed — at least not in the main — to the betterment of human and planetary life, but to the increase of hierarchical power which sabotages human and planetary life as most people now realize (though often without understanding why).

4. In this context, where a great chunk of our social and physical resources are used and abused for power ends, it follows that their prices don’t represent the ‘right’ or ‘proper’ allocation of resources for the good life of people and the planet (don’t know about ‘utility’, since nobody has ever observed and measured it).

-

February 7, 2022 at 8:05 am #247738

Thanks Jonathan. Does CasP envision an alternative economic system to capitalism which would be able to better allocate resources for the betterment of human and planetary life?

-

February 7, 2022 at 4:09 pm #247751

We are fond of autonomy and direct democracy — however far-fetched and unattainable it may seem in the capitalized megamachine that rules our world. Some thoughts on the subject:

The CasP Project (particularly the third part): https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/536/

Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/539/

-

February 7, 2022 at 5:33 pm #247752

Chapter 5 of Tim Di Muzio’s and Richard Robbins’ Debt as Power offers ideas on how to change/improve things centered around reforming our monetary system to eliminate debt-based money (aka credit money). See beginning at page 135 of the pdf (125 of the document): https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/509/

Also, Di Muzio’s The Tragedy of Human Development: A Genealogy of Capital as Power builds on the analysis of Debt as Power and explores how and why the logic of differential accumulation is fundamentally at odds with humanity itself. The book is available online at places like Amazon, but the table of contents and foreword are available here: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/530/

-

-

-

February 9, 2022 at 3:19 pm #247777

I read some of this material. The Debt as Power material provides a program: debt strike to achieve progressive goals. The previous chapter in that work describes a program that could only be achieved as a result of revolution, which is impossible in the US today without violence at a massive scale. Much easier is to organize opposition to proposed policy.

For example, supposed leftists had combined with rightwingers in response to the Berlin Wall in demonstrations to oppose the expenditure of American treasure (deficit spending) and American boys to defend Europeans–why can’t they defend themselves? Alternatively, when the prospect of intervening in Vietnam was being discussed, organizing a similar coalition to oppose intervention. The argument for the left:it’s a war for capitalists, and no tax cuts for fat cats! The argument for the right (why spend billions and sacrifice American boys for a bunch of gooks) and why cuts rich fckrs taxes? The objective would be to prevent the deficit spending resulting from the war and its impact on the gold reserves in Fort Knox:

The implication of the figure is if the spending for the war and tax cuts avoided the decline in gold reserves would not have happened. Had this happened the gold window would not have been closed in August 1971. Gold prices would not then soar, leading to a bull market in commodities that incented commodity producers to believe they could improve their deal by using their cartel powers (e.g. OPEC) to boost prices, thus triggering the stagflation of the latter 1970’s. This led to the “October Revolution” in Federal Reserve policy in 1979 that ended real wage increases for four decades and destroyed the Labor movement.- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Michael Alexander.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Michael Alexander.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Michael Alexander.

-

February 9, 2022 at 3:43 pm #247778

After the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in August 1971, the Fed revolution in October 1979, and the Reagan Revolution over 1981-86, the pre-New Deal world had been reestablished. The Left had been utterly defeated:

Economic inequality soared in response to the environment created by this economic policy. The issue progressives/leftists face today is what to do now? The operating assumption I will use here is it easily to get people together to oppose something rather than to build something. An counterfactual example of this for the modern era would be a Left+Right protest against the TARP in 2008. The core idea for the Left is *all* efforts to prevent financial or economic *collapse* are in the service of the capitalist ruling class and must be prevented. For the Right it is an argument against debauching the currency by “printing money to bail out bankers for their irresponsibility”. That didn’t happen either. But how would that work? Why is this a good idea?

-

February 9, 2022 at 3:54 pm #247779

The answer is this would create a situation like that after the 1929 crash. The result of this crash was a bipartisan increase in the top tax rate from 24% to 63% in 1932 enacted under a Republican president. The reason was fear of inflation. The same fear drove a second tax increase to 75% in 1935 by a Democratic president and Congress and yet more tax increases after war broke out in 1941. This tax policy had unanticipated effects (from chapter 3 of my book–link below):

With the onset of income taxes in 1913, the marginal cost of executive compensation to shareholders is given by the ratio (1−TCorp)/(1−TInd), where TInd and TCorp refer to the individual and corporate tax rates. Marginal cost is the amount of after-tax earnings sacrificed by owners in order to provide an extra dollar of after-tax executive compensation. Very high values of marginal cost would be expected to discourage increases in executive compensation.

Initially, the marginal cost of executive compensation was modest; it averaged about 1.2 over 1913-1931, excluding the period of extraordinary WW I taxation. Furthermore, about half of this period fell into the economic and stock market boom of the 1920’s, during which share owners and their managers did very well. We can assume that the business paradigm was largely SP in 1929, as implied by the high level of inequality then (see Figure 2.1).

Individual tax rates went up to high levels in 1932 and remained there for nearly fifty years. The marginal cost of executive compensation rose to an average value of 3.7 over 1933-1980 and 5.2 over 1937-1963. It made little sense (particularly over 1937-63) to provide high executive compensation, as tax policy had made it very expensive. This new environment of high-cost executive compensation was associated with a lagging trend towards lower levels of executive compensation that lasted until the early 1980’s (see fig)

Executive earnings are adjusted for inflation and economic growth using per capita GDPHigher taxes would be expected to affect stock market values. During the 1930-80 period of high taxes and rising SC (as indicated by falling inequality), the stock market was valued about 30% lower than during the adjacent periods. For example, the ratio of the S&P 500 index to GDP per capita showed average values of 2.17, 1.54, and 2.42 during 1871-1930, 1931-1980 and 1981-2017, respectively. Further evidence of low-valued financial markets during the 1933-1980 period was the absence of asset bubbles or associated market crashes and financial panics. Compare this absence with the three panics in 1873, 1893 and 1907 and the 1929 crash in the pre-1933 period, and the 1987 crash, 2000 internet bubble and the 2008 panic in the post-1980 era.

In an environment of tax-constrained compensation and lackluster stock values, gaining great wealth was hard for executives. Capable pursuit of financial performance as called for by SP culture would not necessarily lead to great wealth, while the depressed market prevented their bottom-line focus to translate into high stock valuations, preventing an acquisition strategy to buy the size that led to prestige. Prestige could still be gained through aggressive organic growth strategies intended to grow large and important corporations. Such strategies require a firm to strongly hire when demand picked up, and to maintain some slack in its workforce when the economy was weak in order to respond quickly to opportunities when they arrived. This necessarily meant higher labor costs. Such strategies would be eschewed by SP managers focused on the bottom line, who would achieve greater profitability, but when compensation did not follow, they would not acquire the wealth symbolic marker. Meanwhile, SC managers, more willing to sacrifice financial performance for growth, would out-expand them, gaining market share and economies of scale that put them at a functional advantage relative to their SP peers in the competition for prestige. In a world of high taxes and depressed stock values, SC culture would prove adaptive.

link to book manuscript: https://mikebert.neocities.org/America-in-crisis.pdf

Besides income taxes, other policies that can help produce depressed stock prices include the following. Raising cap gains tax to 28% and defining long term as 1.5 years rather than 1 year (actual policy in late 1980’s). Repealing SEC Rule 10b-18, making stock buybacks illegal as was the case before 1982.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Michael Alexander.

-

February 9, 2022 at 4:19 pm #247780

Today we face a similar fear of inflation by elites. At some point the stock market will begin to decline. Back in 2007 this decline began in Sept 2007. The TARP issue came a little over a year later, suggesting time to mobilize. It is possible that such a decline has begun, but I am not betting on it, but it could be. There may be potential for action later this year or next year.

So how would this work? The very best case would be if stocks begin a bear market, which then accelerates after the Fed stops QE operations. Meanwhile prices continue to rise. At this point a big chunk of the investor class would be opposed to Fed money creation to prevent stock market declines because of its inflationary connotations. Conservatives could also be opposed to this because of “money creation in service to woke capital” while leftists would understand this to be an effort to preserve capitalist hegemony in our civilization. If I understand correctly, CasP implies that capitalization (discounted future earnings) is power so a decline in this, which would happen in a stock market crash, is a positive outcome.

The question then comes, since a collapse of the economy and financial system generally leads to depression, how does this help the 99%. The answer is it doesn’t, unless one can prevent policy makers from enacting something like the TARP or QE that prevents mass bankruptcies of financial firms. If such bankruptcies happen, then, for a brief period, the 1% and the 99% have objectives that all aligned. Both want reflation of the economy. But such reflated MUST be through stimulation of aggregate demand and not from stabilization of asset values/

-

February 9, 2022 at 8:20 pm #247787

If I understand correctly, CasP implies that capitalization (discounted future earnings) is power so a decline in this, which would happen in a stock market crash, is a positive outcome.

I am not sure how you get from “capital is power” to “stock market crash good.” Seeking to understand capital as a mode of power does not require animosity towards power. Indeed, one of the knocks on CasP is that CasP doesn’t attempt to suggest to us what can/should be done with its conclusions; i.e., CasP lacks praxis. See, Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/539/

I offered up Tim DiMuzio’s Debt as Power because it is the only example of a CasP researcher proposing solutions (twelve of them, of which the debt strike is but one means to implement those solutions) of which I am aware.

-

February 9, 2022 at 11:20 pm #247788

I am not sure how you get from “capital is power” to “stock market crash good.” Seeking to understand capital as a mode of power does not require animosity towards power. Indeed, one of the knocks on CasP is that CasP doesn’t attempt to suggest to us what can/should be done with its conclusions; i.e., CasP lacks praxis. See, Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/539/

Scot’s interpretation differ from Shimshon’s and mine.

We oppose modes of power in general and the capitalist mode of power in particular. The purpose of our research is to understand the capitalist mode of power in order to change it and, if possible, move away from it. I think other CasP researchers share a similar sentiment. Shimshon and I support autonomous, direct democracy, even though this type of society seems far-fetched at the moment and difficult to achieve. The last section of our article ‘Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory’ outlines one possible way to resist and begin to move away the capitalist mode of power — though this type of systemic change is probably impossible to plan more than one or two steps ahead of time.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

February 10, 2022 at 12:56 am #247790

I am not sure how you get from “capital is power” to “stock market crash good.” Seeking to understand capital as a mode of power does not require animosity towards power. Indeed, one of the knocks on CasP is that CasP doesn’t attempt to suggest to us what can/should be done with its conclusions; i.e., CasP lacks praxis. See, Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory: https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/539/

Scot’s interpretation differ from Shimshon’s and mine. We oppose modes of power in general and the capitalist mode of power in particular. The purpose of our research is to understand the capitalist mode of power in order to change it and, if possible, move away from it. I think other CasP researchers share a similar sentiment. Shimshon and I support autonomous, direct democracy, even though this type of society seems far-fetched at the moment and difficult to achieve. The last section of our article ‘Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory’ outlines one possible way to resist and begin to move away the capitalist mode of power — though this type of systemic change is probably impossible to plan more than one or two steps ahead of time.

Do you see any contradiction in claiming, within the same breath, that (1) you’ve outlined “one possible way to resist” and (2) your “possible” way “is probably impossible to plan”?

A way forward that is impossible to plan is no way forward at all, hence the continuing validity of Debailleul’s criticism that CasP lacks praxis (a way to translate theory into practical and concrete action) at the present time.

The fact of your personal animosity (or mine) towards the capitalist mode of power does not affect the objectivity, neutrality or validity of CasP itself, but CasP’s lack of praxis obviates the conclusion that, according to CasP theory, “stock market crash good.”

-

February 10, 2022 at 11:04 am #247791

Do you see any contradiction in claiming, within the same breath, that (1) you’ve outlined “one possible way to resist” and (2) your “possible” way “is probably impossible to plan”?

I believe you are misquoting me. What I wrote was that “this type of systemic change is probably impossible to plan more than one or two steps ahead of time.”

Over the past millennium, the world has seen two major systemic changes: the first, from feudal/autocratic systems to capitalism; the second, from capitalism to state communism (one might argue that the shift from state communism to capitalism marks a third instance — though here the alternative was already present). These changes were largely unplanned.

Conceptually, systemic transitions have two components. (1) the imagined goals of those who seek change and those who try to prevent it; and (2) the actual conflictual process of transitioning from the old regime to the new. In practice, the two components are deeply intertwined and tend to impact each other in complex and often unpredictable ways. This is why I doubt that systemic changes can be planned more than one or two steps ahead of time.

What can be done ahead of time is to analyze the existing system to understand its strength and weaknesses and to determine, as much as possible, what parts of it are desirable and what aren’t — with the explicit recognition that these analyses are tentative and will likely be modified.

Finally, and importantly, I think that analyzing an existing system, however critically, lends only limited insights into what should and could replace it. When you criticize an existing system, you dissect what is. When you conceive/build an alternative system, you create something new. And, for the most part, the act of creating a new social order — particularly when this creation is conflictual and complex — cannot be easily deduced, if at all, from the analysis of the old.

In my view, this conflictual act of creation is the main reason why ‘Marxist praxis’ has had little to do with Marxist analyses of capitalism, and it is also the reason why CasP theory per se can tell us very little about autonomy and direct democracy, let alone how to get there.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 1 month ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.