Home › Forum › Political Economy › Is capital finance and only finance?

- This topic has 30 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated January 23, 2022 at 7:59 pm by Michael Alexander.

-

CreatorTopic

-

November 8, 2021 at 7:57 pm #247144

[jmc: This conversation was originally in the Q+A for new readers, but it might be too technical for someone being introduced to political economy and the capital-as-power approach. It has been moved here, so the conversation can retain its level of detail.]

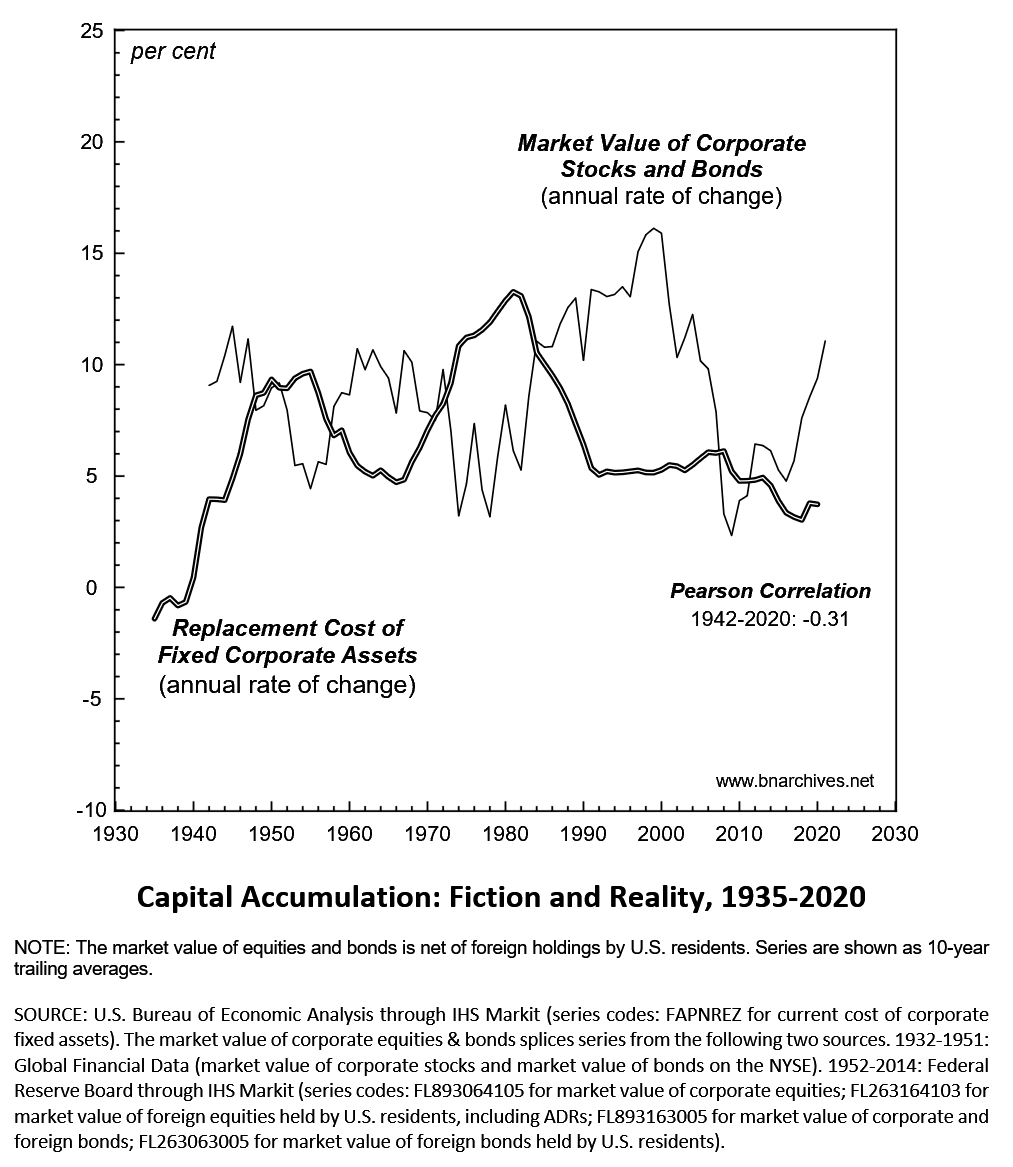

Scott, Our claim that “the quantum of capital exists as finance, and only as finance” can be clarified by breaking it into two parts. (1) Capital is finance. For capitalists, “capital” are record of ownership (stocks, bonds, real-estate claims, etc.) whose quantity is their forward-looking pecuniary capitalization, and forward-looking capitalization is a financial quantum: its magnitude is risk-adjusted expected future earnings discounted by the normal rate of return. (2) Capital is only finance. The common view that capital=capital goods breaks down because amalgams of heterogeneous capital goods cannot be measured in meaningful ‘real’ units (physical volume, weight, embodied energy, etc. although universal, are not meaningful). Furthermore, even when we measure the money magnitude of capital goods rather than its so-called real magnitude, its movement has little or nothing to do with that of capitalization. In the U.S., the two move in opposite directions.

The fact that records of ownership are held by financial institutions is immaterial for these arguments. You could hold them under the mattress and they would still be finance and only finance.

Jonathan,

Thank you. I have a couple of follow-on questions to clarify.

First, CasP’s definition of the “financial quantum” of capital is specifically based on stocks. Other types of financial assets, e.g., bonds, are priced differently, but like stock prices, bond prices are related to the net present value of future income arising from the bond. What about bank deposits, the value of which are always the par/nominal value of money deposited (assuming no accruing of interest)? Does CasP consider bank deposits as capital? Or does it view bank deposits as “money,” even if it is not in circulation (as the Federal Reserve does)?

I view bank deposits as capital because they are a claim to money, not money itself.

Second, I agree that the “holder” of the record is immaterial, but is the counter-party to the underlying claim also immaterial? Being the aggregator of and counter-party to all capital imbues Finance with immense power, even though that capital is officially owned by and owed to others.

Another way to say it is that, in theory, the nature of capital is the same regardless of the counter-party, but, as a practical matter, who the counter-party is/are can affect the distribution of power capital represents. Capitalist wealth depends on the ability of Finance to make good, which requires keeping Finance healthy.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

November 8, 2021 at 8:23 pm #247146

What about bank deposits, the value of which are always the par/nominal value of money deposited (assuming no accruing of interest)? Does CasP consider bank deposits as capital? Or does it view bank deposits as “money,” even if it is not in circulation (as the Federal Reserve does)?

We think of bank deposits that pay no interest as capital with zero expected profit. The same applies for any other ‘income-less’ asset.

Second, I agree that the “holder” of the record is immaterial, but is the counter-party to the underlying claim also immaterial? Being the aggregator of and counter-party to all capital imbues Finance with immense power, even though that capital is officially owned by and owed to others.

I’m not sure what you mean by ‘Finance’ with a capital F. We speak about finance with a lower-case f. For us, finance is an operational symbol (in Ulf Martin’s terminology), and that’s it. What most people think of when they speak about Finance is the FIRE sector (finance, insurance and real estate). In our view, this sector is not finance, but merely one institutional/organizational manifestation of finance. As we see it, the FIRE sector, however large, does not control money, credit and debt; the “state of capital” does. It is the ruling capitalist class, its key corporate and government organs and their many-faceted institutions that together dominant and steer the financial process. Banks, insurance and real-estate companies are merely part of that process.

Now, having said that, you are correct that FIRE can and does redistribute income, risks and assets — but so do other sectors, such as raw materials, pharmaceuticals and high-tech firms, sometimes at cross-purposes, sometimes in unison. These redistributional patterns are the details of the differential process of ‘credit at large’ — not the process as such.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

November 8, 2021 at 10:12 pm #247148

Second, I agree that the “holder” of the record is immaterial, but is the counter-party to the underlying claim also immaterial? Being the aggregator of and counter-party to all capital imbues Finance with immense power, even though that capital is officially owned by and owed to others.

I’m not sure what you mean by ‘Finance’ with a capital F. We speak about finance with a lower-case f. For us, finance is an operational symbol (in Ulf Martin’s terminology), and that’s it. What most people think of when they speak about Finance is the FIRE sector (finance, insurance and real estate). In our view, this sector is not finance, but merely one institutional/organizational manifestation of finance. As we see it, the FIRE sector, however large, does not control money, credit and debt; the “state of capital” does. It is the ruling capitalist class, its key corporate and government organs and their many-faceted institutions that together dominant and steer the financial process. Banks, insurance and real-estate companies are merely part of that process. Now, having said that, you are correct that FIRE can and does redistribute income, risks and assets — but so do other sectors, such as raw materials, pharmaceuticals and high-tech firms, sometimes at cross-purposes, sometimes in unison. These redistributional patterns are the details of the differential process of ‘credit at large’ — not the process as such.

Thanks for your response regarding bank deposits. It was very helpful.

I need a little help understanding the rest of your response.

What/who was the “operational symbol” of Mumford’s original Mega-Machine? Was it the king?

Is there a hierarchy in the operational symbol that is finance?

Isn’t CasP’s “state of capital” just a different label for an operational symbol that includes finance, albeit one that is more fuzzy and amorphous than finance or the FIRE sector? Is there a reason for maintaining the concept of a ruling capitalist class in lieu of being more specific about what “the state of capital” is?

Approaching these questions from an entirely different angle, have you considered (or do you assert) that the “state of capital” is logically distinct from the state within whose laws the state of capital operates? I am not trying to argue in favor of the false dualities (normative myths) of politics-economics and real-nominal, but a case can be made that, within any capitalist society, there are two poleis, each with a distinct political economy governed by different rules and laws (I have started modelling this), where the second polis (the state of capital) controls the first polis (the state) for the benefit of the second polis. From this perspective, capitalism is not a mega-machine, it is a control system (mode of power) whose logic organizes and controls the mode of production for the purposes of perpetuating its control (power).

Thank you again for the time you have spent in answering my questions. Your answers have been very helpful in further defining the current metes and bounds of “orthodox” CasP theory (when you add the scare quotes, the term is not an oxymoron).

P.S. I use the term “control system” as an electrical engineer would, and I am thinking specifically of the social analog of a space-state control system (something I learned about in my “Robot Manipulation” class in undergrad).

-

November 9, 2021 at 3:33 pm #247149

Broad concepts/metaphors are always loose and contested.

What/who was the “operational symbol” of Mumford’s original Mega-Machine? Was it the king?

According to Ulf Martin’s The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery, ‘operational symbolism’ appeared only in modernity. The kings in Egypt and Mesopotamia were still locked into ‘magical symbolism’.

Approaching these questions from an entirely different angle, have you considered (or do you assert) that the “state of capital” is logically distinct from the state within whose laws the state of capital operates?

The concept of the ‘state of capital’ begins by defining the ‘state’ as the overall power structure of society and then attributing to it a particular form – ancient kingship, feudal, capitalist, etc. For us, the ‘state of capital’ is a synonym for the ‘capitalist mode of power’. As we see it, the state of capital is the broadest definition of the regime and, in that sense, it contains – rather than being contained by – the normal conception of the state. Thus, in our view, what people normally refer to as the ‘U.S. state’ is part of the state of capital, not the other way around.

From this perspective, capitalism is not a mega-machine, it is a control system (mode of power) whose logic organizes and controls the mode of production for the purposes of perpetuating its control (power).

Isn’t a megamachine a control system? My impression is that this is exactly what Mumford had in mind. But then, metaphors are merely tools to contextualize/enrich/sharpen our understanding, so you can definitely change them to suit your purpose.

-

November 9, 2021 at 8:12 pm #247152

Approaching these questions from an entirely different angle, have you considered (or do you assert) that the “state of capital” is logically distinct from the state within whose laws the state of capital operates?

The concept of the ‘state of capital’ begins by defining the ‘state’ as the overall power structure of society and then attributing to it a particular form – ancient kingship, feudal, capitalist, etc. For us, the ‘state of capital’ is a synonym for the ‘capitalist mode of power’. As we see it, the state of capital is the broadest definition of the regime and, in that sense, it contains – rather than being contained by – the normal conception of the state. Thus, in our view, what people normally refer to as the ‘U.S. state’ is part of the state of capital, not the other way around.

Whether the “state of capital” contains the the “U.S. state,” or vice versa, does not make them one and the same. Indeed, there are logical distinctions between the two that are readily identifiable by how the laws operate within each domain. These distinctions are especially easy to see when you study the history of American law and how it was transformed over two hundred years to establish the dominance of capital in the U.S.

The false duality (normative myth) of politics-economics drove legislatures to create a separate legal regime/domain ruled by capital (in much the same way the separation of church and state carves out a regime/domain for religions). CasP already recognizes that each regime has different rules for pricing, but they also have different laws for liability and taxation, all of which contribute to the ability of the capital domain to create and deploy power (as capital).

Since you took us back to the “capitalist mode of power,” to what extent are such logical (and/or legal) distinctions between the “state” and the “state of capital” that contains it reflect the mode of power, as opposed to one of its supporting “concepts of power”?

Let’s look at capital itself. All capital begins as money. All money begins as fraudulently-induced indentured servitude: in our privately controlled credit-money system, the only thing of value that is exchanged in a transaction that creates credit-money is the promise to pay the creditor subject to compounding interest; however, the creditor has no explicit right under the law to create money, which requires no work on the creditor’s part, and any “risk” taken on by the creditor is the same as the risk involved in any act of fraud. Therefore, all capital begins as indentured servitude.

Is credit-money creation part of the capitalist mode of power, or an underlying concept of power? What about indentured servitude?

Compounding interest is the inverse of discounting. If you leave aside inflation, the interest rate and discount rate are the same for any financial asset, particularly for debt-based instruments such as mortgages or bonds. Compounding rates lead to exponential growth.

Is the interest/discount rate part of the capitalist mode of power, or an underlying concept of power?

What about the differences in pricing commodities v. pricing financial assets?

Another way of approaching these questions is, as we map out how power is created and flows through a capitalist system, how do we know what belongs to the mode and what is a “concept”? Using a computer analogy, is the mode the “hardware” and concepts the “software,” the processes executed by the software? Or is the “hardware” just the mode of production, and both the mode of power and its concepts are lumped into the “software”?

It all seems to go back to metaphors, but I will take something more concrete, if you’ve got it.

-

November 9, 2021 at 10:16 pm #247154

Scot,

You raise many questions, but I think that, at this point, engaging with them will be splitting hair. Perhaps when you write something concrete where these issues become paramount, we can revisit the various metaphors and categories and see whether our differences, if any, matter or not.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

November 10, 2021 at 5:55 pm #247156

Scot, You raise many questions, but I think that, at this point, engaging with them will be splitting hair. Perhaps when you write something concrete where these issues become paramount, we can revisit the various metaphors and categories and see whether our differences, if any, matter or not.

Works for me. I will post “something concrete” under a new topic in a little bit, most likely “Modelling the State of Capital.”

–Scot

-

November 28, 2021 at 11:26 pm #247239

Is CasP theory limited to describing the behavior/power of dominant capital?

If not, to what extent does CasP theory explain the behavior/power of capitalists, generally, individually and with respect to dominant capital?

If so, is there any reason why CasP theory cannot be extended to capitalists, generally and individually, as distinct from the corporations that form the core of dominant capital? (Capitalists are not capitalized, only firms are capitalized, and differential capitalization only results in differential accumulation for the individual capitalist when he locks in gains by selling his shares.)

-

November 29, 2021 at 9:19 pm #247242

In the first chapter of our 2009 book, ‘Capital as Power’, we wrote a bit about the limits our journey:

The study of capital as power does not, and cannot, provide a general theory of society. Capitalization is the language of dominant capital. It embodies the beliefs, desires and fears of the ruling capitalist class. It tells us how this group views the world, how it imposes its will on society, how it tries to mechanize human beings. It is the architecture of capitalist power. This architecture, though, tells us very little about the human beings who are subjected to its power. Of course, we observe their ‘behaviour’, their ‘reaction’ to capitalist threats, their ‘choice’ of capitalist temptations. Yet we know close to nothing about their consciousness, awareness, thoughts, intentions, imagination and aspirations. To paraphrase Cornelius Castoriadis, humanity is like a ‘magma’ to us, a smooth surface that moves and shifts. Most of the time its movements are fairly predictable. But under the surface lurk autonomous qualities and energies. The language of capitalist power can neither describe nor comprehend these qualities and energies. It knows nothing about their magnitude and potential. It can never anticipate when and how they will erupt. (19-20)

We then went on to explain why this was the case.

In our view, anything that is conditioned and creordered by the logic of capital as power — including capitalists of all types, workers, corporations, labour unions, governments, NGOs, international organizations, crime networks, etc. — can be theorized and researched by CasP.

But things that lie outside this logic — particularly alternatives to it — cannot be.

The line separating these two categories of course is open to debate.

-

November 29, 2021 at 9:51 pm #247245

In our view, anything that is conditioned and creordered by the logic of capital as power — including capitalists of all types, workers, corporations, labour unions, governments, NGOs, international organizations, crime networks, etc. — can be theorized and researched by CasP. But things that lie outside this logic — particularly alternatives to it — cannot be. The line separating these two categories of course is open to debate.

That is helpful. Thank you.

I view CasP’s logic as tailored to the dominant capital and capitalism of today, but I don’t think the capitalism that existed prior to the modern limited liability corporation or stock markets lies outside of that logic, if it is modified to account for the limited number of tools in the creorder toolbox. Capitalist power is fractal, which involves self-similarity, not exact replication. This issue is what prompted my question: is it fair to translate/modify CasP’s logic to account for differences in the stage of capitalism’s development or the position of the capitalist within the capitalist hierarchy?

For example, I think it would it be fair to consider the financial wealth of an individual capitalist as her “capitalization.” Although she, herself, is not divisible into shares and vendible on a stock market, her financial wealth is denominated in monetary units whose value is determined by the discounting/capitalization ritual, which was true before stock markets were well established (e.g., when “stocks” were typically bonds and other debt instruments, not shares of corporations). Thus, CasP’s logic still applies to the individual capitalist, although “differential accumulation” likely means something other than what it means for dominant capital, e.g., there are no depth or breadth regimes for the individual except indirectly.

-

January 13, 2022 at 1:00 pm #247522

I have some quibbles with these definitions. Capital is defined financially, in terms of market capitalization. Capital has a second definition as the means of production. Put another way, we can say, the “resources employed by businessmen to produce a profit”. This is the definition I gave to what I called Business Resources or R. R is also defined as the cumulative sum of retained earnings on the S&P 500 in constant dollars plus the real value of the index in 1871, when data becomes available. To the extent that the S&P500 index is representative of the economy as a whole, R can function as a proxy for the amount of real capital in the economy. This figure shows a plot of R and per capita GDP since 1871.

With R representing the “real capital”, and the price of the index representing “financial capital” one can relate the two in terms of the ratio P/R. This is the financial value for capital compared to real value for capital and could be used as a tool for determining how over or under valued the market is at any point in time. Such a plot shows range-bound behavior for two centuries.

In recent years P/R has risen above its previous high in 2000 which is either indicative of a massive bubble that will correct downward at some point, or an entirely new mode of capitalist operation. I note that the concept of capital as R is essentially the same as the Marxian notion of capital as the means of production.

Now a main point of my book is that capitalism is a cultural construct (like everything else in the human world) and evolves just like other kinds of culture. So on can apply the methods of cultural evolution as developed by Boyd, Richerson, Henrich, and others to evolution of capitalism. I use a very simplified model involving two kinds of capitalism, shareholder primacy (SP) and stakeholder capitalism (SC). The first uses the financial definition of capitalism, while the second uses the Marxian one. Which one you get depends on the economic and business environment. An environment of low marginal tax rates on income, low tariffs, inflation control using interest rates, legal stock buybacks, such as we have had since the 1970’s, selects for the SP variant. An environment of high marginal tax rates, high tariffs, fiscal inflationary control, and illegal stock buybacks selects for the SC variant. I use a measure of income inequality (top 1% income share) as a proxy for the amount of SP capitalism. Using a cultural evolutionary model I got from Boyd and Richerson’s primer on the topic I obtain this result when fitting inequality data to the model

Here “E” refers to the environment in which capitalist evolution is taking place. It is a function of policy set by the state: here represented as a linear function of top tax rate and labor power (measured by strike frequency). The heavy black line is the cultural evolutionary response to the changing environment E, and the open symbols is top 1% income share used as a proxy for amount of SP culture versus SC culture. -

January 13, 2022 at 1:52 pm #247523

I have some quibbles with these definitions. Capital is defined financially, in terms of market capitalization. Capital has a second definition as the means of production. Put another way, we can say, the “resources employed by businessmen to produce a profit”.

CasP theory explicitly rejects the second definition.

For the single best CasP discussion addressing most, if not (more than) all, of your points, see Bichler’s and Nitzan’s 2015 article Capital Accumulation: Fiction and Reality. https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/456/

If you haven’t already done so, you may also want to read the 2009 book, Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder, which is available in its entirety (and for free) here.

-

January 13, 2022 at 8:13 pm #247524

Thank you Michael Alexander for the interesting note. Three points.

1.

You define:

R = ‘real’ cumulative retained earnings = cumulative (retained earnings / price index).

According to this definition, R is an aggregation of the ratio between two nominal series. I don’t know how this aggregation is a proxy of ‘real’ capital — first, because retained earnings are at best the consequence of ‘real’ capital; and second, because ‘real’ capital, understood as a material/productive entity, is unknowable to anyone and everyone, including economists. Yes, Marxists claim that the ‘capital stock’ is ploughed-back surplus value (incarnated as ‘real’ retained earnings), though you cannot operationalize this claim with historical summation when prices deviate from values (whatever they might be) and when technical change makes existing plant and equipment useless/worthless to an unknowable degree.

2.

You define:

P/R = S&P 500 price index / R = S&P 500 price index / cumulative (retained earnings / price index).

This is a relationship between three nominal indices. It is bounded because the denominator R is a rising series with the same slope as the stock market trend. Take any other rising series with a similar slope — or the stock market trend for that matter — and you get the same result.

3.

I’m not sure I understand your last chart and associated explanation.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

January 16, 2022 at 5:58 pm #247542

R is not cumulative retained earnings divided by a price index.

Back in the day, when a firm made a profit it paid out most of it to the owners, but retained a fraction that increased the assets held by the first by the amount retained. This made the company worth more by the amount retained (in theory). Over time the amount the firm was “worth” at time t was he amount it sold for at time zero plus the amount of profits retained over the intervening t years. This figure of cumulative retained profits is reported in a company’s statement of assets. Such information was private and sometimes kept secret for the public. Thus a stock market operator would try to sniff out hidden assets, acquire a position in the company and then publicize the assets, after which the price would rise to match the asset amount at which point the operator would sell. In other words, valuing a companies based on its net equity *worked* to reflect real prices, people made money this way and everyone knew this was how valuation worked. It was common knowledge that a company was worth its equity value, that is the amount of profits it had made (and kept) over time.

This stopped working when secular inflation became a thing and now equity or book value is pretty much meaningless.

R is this same equity calculation, except rather than use the nominal dollars I convert them to constant dollars and then sum them up. Unlike conventional equity, R continued to work for the stock indexed right up to 2000 when I used it to forecast a secular bear market in my first book Stock Cycles. It has only been in the last year or so that valuations have risen out of their historical range, making P/R no longer useful for valuing the index.

Although R can be calculated using financial data, it is *not* a financial quantity. It does not work for individual firms, but only for the index. There is no financial or economic reason for why this thing should show the same slope as the index, and indeed, it no longer seems to be doing so, but it did for nearly 150 years, for no apparent reason. It apparently measures something–it tracks per capita GDP over time, which is weird.

It is structured as a cumulative constant-dollar equity. Return on equity (ROE) is often seen as the same thing as return on capital (ROC). Based on this sense, R can be thought of as cumulative real capital or capital accumulation, which is consistent with the correlation between GDPpc and R. So years after coming up with R it occurred to me that perhaps R is a proxy for capital.

I did conceive of R as a cultural thing back then because there are several paragraphs in Stock Cycles that describe is as such, although culture was a fuzzy concept in my thinking at that time. Since learning about cultural evolution and cliodynamics and the mathematical apparatus for dealing with fuzzy things like culture more has fallen into place.

What you are doing with nomos and capital as power is along the same lines as my approach with capitalism as culture. But I would argue that power itself is a cultural manifestation and so ultimately falls under the capitalism as culture paradigm.

-

January 16, 2022 at 6:06 pm #247543

As for point 3, this is best addressed by either reading my peer-reviewed paper on it

https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9x36913k

or sections 3.4 through 3.6 from my recent manuscript:

https://mikebert.neocities.org/Sec-cycle-book/secular%20cycles%20book-endnote.pdf

-

January 16, 2022 at 7:05 pm #247544

P/R is not a ratio of three indices. It is market price of a share divided by the equity value per share with equity calculated on a constant-dollar basis.

The idea is that when a firm retains profits, they are invested in non-money, or “real” objects, the prices of which rise with inflation.

For example, earnings on the S&P500 precursor in 1871 was 40 cents, while the dividend paid out was 26 cents. The index itself was $4.69. Retained earnings were $0.14. If we add this to the value of the index, we would say it was now “worth” 14 cents more or $4. 83. If we continue to 1910 this cumulative sum had risen to $9.93. More than half of the “worth” of the index was the result of profit generation (and retention) over the preceding 39 years. The index in 1910 was prices at $9.4. Here we see how the market price kept track with rising retained profits, or “equity”.

Continuing on for another forty years to 1950 the equity has now reached $24.05, while the index was now priced at $18.4, suggesting 1950 was a buying opportunity. And if we go another 40 years to 1990 equity has reached $193, while the market value was 335, suggesting the index should be sold as it was way overvalued. This was clearly wrong as subsequent market action revealed.

But if I do these same calculations by first putting the retained earnings for each year (and the initial index value) into constant dollar terms and then perform the same equity calculation I obtain the following values for 1910, 1950 and 1990: 9, 45.2, and 617. Here R correctly predicted that the index was very undervalued in both 1950 and 1990, which subsequent market action indicated was correct. Ten years later R has risen to 900, while the index now stood at 1427, way higher. Now R was indicating overvaluation. Old-school equity had been saying markers were overvalued for decades (and been wrong) while R was saying they were undervalued and had been right. Now it was the chance for R to be wrong. It wasn’t, future market action confirmed that assessment. By 201o R has reached 1572, while the index stood at 1139, suggesting undervaluation, which was confirmed by subsequent market action. But by 2019 R has reached 2400 while the index was now over 2900. R was no saying the market should fall in the future. And it did try to fall in March 2000 but then rose to dramatically higher levels because of Fed intervention. So R has now also been invalidated but that reflects external factors not accounted for in the R model.

P/R was invented as a tool for valuing the S&P 500 index. And it seems to have worked, giving correct assessments and allowing be to make a successful prediction back in 2000:

https://www.amazon.com/Stock-Cycles-Stocks-Markets-Twenty-ebook/dp/B0791LWTNK

-

January 17, 2022 at 9:15 am #247546

R is not cumulative retained earnings divided by a price index.

P/R is not a ratio of three indices. It is market price of a share divided by the equity value per share with equity calculated on a constant-dollar basis.

I must admit being confused. Forgive me if you have already done so, but could you provide a simple definition + a clear example for both R and P/R?

-

January 17, 2022 at 10:09 am #247547

This is from Appendix A in Stock Cycles

For an index, R is given by:

A.1. R = R0 + sum of {(Ei-Di) · $CPIi } for i = 0 to i

Here Ei and Di are the earnings and dividend on the index at year i. The parameter $CPIi is the value of the historical dollar in year i in terms of 1999 dollars. The parameter R0 refers to the value of R in a basis year also expressed in 1999 dollars.

In the text R was introduced as follows:

In order to define the secular trends/stock cycles; it is useful to express the index value in terms of a parameter that is bounded (restricted to a range of values). An example of such a parameter is the price to earnings multiple or P/E. Stocks go up over time because earnings rise. The ratio P/E does not have to rise for stocks to go up, and P/E will generally remain within a range of values over very long periods of time. By using a bounded parameter like P/E, it should be possible to define stock cycles in terms of cyclical movements in the value of the parameter.

Since the cycles we wish to describe are quite long (28 years on average) P/E is not a good choice for this parameter. P/E fluctuates between high and low values more frequently than we would like for a 28-year cycle. The parameter I invented for stock cycles is P/R, the ratio of the index value (P) to business resources (R). Resources are simply the things (plant, equipment, technical knowledge, employee skills, market position etc.) available to the business owner to produce a profit. For a broad-based index, the value of R can be estimated as the sum of retained earnings in constant dollars as given by equation 3.1:

3.1 R = R0 + sum of rrEi for i = 0 to i

Here rrEi stands for the real retained earnings in year i. That is, it is the difference between what the stocks in the index earned collectively in year i and the dividends paid out in that year, expressed on a constant-dollar basis. R0 is the value of R in some basis year. For example, R for the S&P500 in fall 1999 was $950. Of this value, $880 represents the sum of rrE for 1999, 1998, 1997 all the way back to 1871 (all expressed in 1999 dollars). The remaining $70 represents the value of R in 1871 (R0).

P/R is just the S&P 500 index value divided by R. R tracks P for similar reasons as why E tracks P over time.

-

January 17, 2022 at 11:26 am #247548

Thank you for the clear explanation, Alexander.

Here you say:

R is not cumulative retained earnings divided by a price index.

But here you seem to say the opposite:

For a broad-based index, the value of R can be estimated as the sum of retained earnings in constant dollars

Reading your explanations, it seems to me that you express the common backward-looking notion of ‘real capital’ — namely, that this ‘stock’ is made of past earnings invested in plant, equipment, raw material, knowledge, etc. If I understand you correctly, the difference is that you don’t call this magnitude ‘real capital’ but ‘resources’.

I’m not sure how your view relates to Capital as Power, particularly given (1) that CasP rejects the notion that ‘real capital’ has an objective magnitude, and (2) that capitalization, being the discounted value of risk-adjusted future earning, is theoretically independent of past profit, aggregated or otherwise.

-

January 17, 2022 at 6:39 pm #247550

First point, I interpreted cumulative retained earnings divided by a price index to mean (cumulative nominal retained earnings) divided by a price index, whereas it is cumulative (nominal retained earnings divided by a price index) or cumulative real retained earnings, they are different things.

Yes R contains past invested earnings, but not just invested in plant, equipment, raw material, knowledge, etc. 20 years ago most retained earnings were invested in stock of other companies through acquisitions and mergers. In terms of R what is being purchased is some other companies R which then gets added to your R. Tobin’s Q involves investment in the plant, equipment, raw material, knowledge, etc, but it failed as a valuation tool because it did not account for investment as mergers and acquisitions in which what is being bought is entirely intangible or in the case of stock buybacks, nothing. And yet nothing can be financially potent–look at cryptocurrencies. I used resources to separate R from the idea that it represented lant, equipment, raw material, knowledge, etc, because otherwise one can just use Tobin’s Q.

You write “capitalization, being the discounted value of risk-adjusted future earning, is theoretically independent of past profit.” But it’s not. Future earnings is not a thing theoretically because it is unknowable and so meaningless. Practically, for an index like the S&P500, it is pretty easy to predict. Plot log earnings over time and you get a pretty straight line so one can forecast future earnings by extrapolation of a fairly constant rate. The discount rate r is an arbitrary parameter that one can adjust to fit the data. This means that actual future earnings (EPS) divided by r can be represented by an adjustable parameter, k, times the present EPS (E) with which we can write eq 4 on p 189 as

P = (EPS / r) * H = k * E * H = E * (k * H) = E * (P/E)

In other words, one can represent the meaning of H using the index P/E, which varies widely over time, showing how hype changes. One of the factors affecting P/E or hype is the length of the amount of time the financial expansion has one on. The longer it does the greater the hype.

By introducing discounted future earnings you confuse the issue. What are the future earnings for cryptocurrencies or NFT? Yet these have prices and are a multitrillion dollar thing. The same thing could he said about internet stocks in the late 1990’s which is the environment in which I wrote Stock Cycles. Sure pets.com was worthless, but you couldn’t short that stock back then anymore than you can short Bitcoin today.

R represents an abstraction of the idea of “real capital.” Capital in the sense of plant, equipment, raw material, knowledge, etc should “work” for individual companies. R explicitly does not. This was shown by the stock prices tech companies with little (or no) earnings were fetching in the 1990’s. This was my take on what R meant in 2000:

**********************************

The underlying meaning of R is subtle. Some resources are physical assets such as plant and equipment, natural resources, or land that can be counted and which will show up on a balance sheet. Most of R resides in the brainpower of workers, however. A company in a declining industry will provide an environment that is less conducive to profit generation than a company in a rising industry. As a result the declining firm cannot attract and retain as many high-caliber employees, and they lose R as a result. Companies in rising industries gain increasing numbers of talented employees and gain R. In a way the new employees bring a little R with them when they join a company.New employees are not blank slates. Generally they can already communicate and process information. Often they already have specialized functions and knowledge bases. That is, they are an asset that produces a return, or they carry a little bit of R with them. Now where did they get this R? They got it as part of the cultural transmission they received from the previous generation. This quality of this transmission is a function of the richness of the cultural milieu in which the new worker was raised. The richer the milieu, the more R. As a result of the accumulation of past retained earnings, companies grow and pay increasing wages to workers, which makes society richer over time. The richer society provides an ever-improving cultural milieu in which the next generation is raised. Hence, successive generations have more R than the previous generations. For example, this rising R per worker is manifested by the tendency for population-average IQ scores to rise over time.

***************************This is a crude idea, but it contains the germ of the idea of capital as a cultural variant*, which is a non-economic thing, just as is your conception of capital as power.

*Theoretically capitalism is a social scale-up technology like religion or the state. The latter two increased group power (and so resistance to conquest) by increasing population size and/or social cohesion. Capitalism enhanced the amount of state power derived from a given population by boosting (taxable) economic output per person. This enhanced the ability of states/monarchs with this cultural attribute to contend with competitors leading to the spread of the capitalist cultural variant.

-

January 17, 2022 at 7:31 pm #247551

Thank you Alexander for this interesting view.

You might find CasP analyses of the stock market useful, even if you disagree with them:

- A CasP Model of the Stock Market (2016) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/494/

- Financial Crisis, Inequality, and Capitalist Diversity: A Critique of the Capital as Power Model of the Stock Market (2020) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/599/

- How the History of Class Struggle is Written on the Stock Market (2020) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/658/

- Reconsidering Systemic Fear and the Stock Market: A Reply to Baines and Hager (2021) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/696/

- The Ritual of Capitalization (2021) https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/707/

-

January 18, 2022 at 12:38 pm #247576

I looked over the stock market model paper. I also looks at the intro to the critique paper which provided a neat summary of the model:

A ‘power index,’ calculated by dividing the S&P 500 share price by the average wage rate from the late nineteenth century to the present, is tightly correlated with total returns for the S&P 500 twelve years later.

The power index is a detrended stock index, where a wage series is used for detrending. It provides a way to measure valuation levels that allows comparisons over time. There are lots of detrended indices, one of these is P/E, which Robert Shiller converted into his CAPE index that when presented to the Fed led to Greenspan’s “Irrational Exuberance” speech. Tobin’s Q is another example, as is Hussman’s valuation measure, and my own P/R.

In my own case, P/R reached its “irrational exuberance” moment in summer 1999 (see http://web.archive.org/web/20040406095317/http://csf.colorado.edu/authors/Alexander.Mike/Stanpor3a.html).

P/R gave a usable sell signal (I did sell in 1999 and it was a good move), whereas CAPE and Tobin’s Q were too early. P/R gave buy signals in July and Oct 2002 and in Nov 20 2008, which were also usable signals. It then gave sell signals in 2014 and 2020, which were wrong. All these are crude valuation-based predictions I used to test the validity of the valuation tool. What Hussman does is more sophisticated as he also uses a model based on technical analysis—which helps him avoid jumping the gun like I did.

We can use the power index to make predictions just as I did with P/R, when I was testing the concept. The close correspondence between the power index and Hussman’s valuation measure (see Fig 5 in model paper) to allow us to use 1% projected return (due to overvaluation) starting in 2013 (see Fig 4) to make short term predictions. The market in 2013 was at about 1600, while today it is 3000 points higher. According to the power index the 12-year return after 2013 are going to be low–in the 1% range. That is roughly similar to dividend yields which means the power index is forecasting that by 2025 we should see the index return to the neighborhood of 1600.

It will take about two years to get there, so we should see a big bear market beginning around the end of this year give or take six months, and probably an associated recession in 2023. How would that happened. I would guess it would reflect a growing sense that the Fed has dropped the ball on inflation, possibly because high inflation persists into the second half of this year, which is not what most people expect. A few years will tell the tale, lets’ see what happens. I hope it does, I sold out most of my stock positions back in 2013 based on Stock Cycle-based analysis, which is why I dropped work with long cycles in 2014 and started working with a new paradigm in my social science hobby.

-

January 18, 2022 at 6:26 pm #247577

I plotted out systemic fear and was looking at it. My understanding is system fear is associated with capital power. So I added labor power as proxied by strike frequency.

I would expect the two series to be inverses of each other, as in when capital power is high labor power is low and vice versa. This is the case for the measure I use for capital power, what I call the investment index, which is a ratio of the value of a portfolio of 50-50 stocks and bonds after taxes divided by a wage series. Here is investment index and labor power.

-

January 19, 2022 at 2:37 pm #247582

I have been thinking about the problem of what is capital and capitalism. A problem I have with capitalism as power and capital as sabotage of industry is the startup problem. How can capitalist power be exerted when it is weak compared to other powers? And how can sabotaged industry come to dominate over non-sabotaged industry?

I prefer to think of capitalism as husbandry. A dairyman cares for his cattle so that he may extract their milk for his own purposes. A would-be dairyman can do the same by buying a breeding pair of cattle and then growing his own herd. Similarly, the capitalist husbands industry so that they may extract profit from that industry. A would-be capitalist can buy a bit of industry and grow it into a bigger industry. There is no start up problem.

So what is capital? Capital is what capitalists buy with their profits. This is a definition, it comes from Immanuel Wallerstein who defined capitalism as “the ceaseless accumulation of capital” an idea I believe originated with Marx (though I may be wrong here). Now one thing capitalists acquire a lot of is firms, through merger and acquisition deals. So let’s think of capital as whatever makes firms worth buying. Now CasP sees future earnings as what makes firms worth buying and that certainly is a valid way of looking at it. But the future profits are *not* necessarily connected with the thing that is being purchased. For example, the capital purchased when auto firms bought electric trolley firms was to be destroyed, there would be no future earnings coming from that specific capital. But doing this was expected to increase the profitability of their other capital (that related to autos). So, the auto firms *were* buying future earnings (i.e. capital) when they bought the trolleys, it just was capital that was never owned by the trolley companies. It had been *created* by the trolley companies and was real (this is why the auto firms had to *buy* it) but it did not ever belong to the trolley companies (because it was only fully manifested by the auto companies who bought them). Hence capital, though accumulated by individual firms, does not necessarily belong to them.

So rather than trying to measure capital in terms of an unknowable future stream of profits (that might not even materialize like that of the trolley companies before they were bought) why not measure it by the price (adjusted to constant dollars) that capitalists paid for it when they acquired it? That’s what R does.

-

January 20, 2022 at 11:36 am #247587

Thank you Alexander.

I have been thinking about the problem of what is capital and capitalism. A problem I have with capitalism as power and capital as sabotage of industry is the startup problem. How can capitalist power be exerted when it is weak compared to other powers? And how can sabotaged industry come to dominate over non-sabotaged industry?

Some ideas about how capital as power was born out of feudalism can be found in Capital as Power, Ch. 13: ‘The Capitalist Mode of Power’.

So what is capital? Capital is what capitalists buy with their profits.

On an aggregate level, what capitalists buy with their profit is plant & equipment, or what economists call ‘real capital’ (buying other companies through mergers or acquisitions doesn’t alter the aggregate of what capitalists own, only redistributes it among them). The problem is that, over the longer haul, the growth rate of the replacement dollar value of ‘real capital’ (economic accumulation) moves inversely with the dollar value of stocks and bonds (financial accumulation). And since for capitalists the key is the latter process rather than the former, economists end up barking up the wrong tree. Here is a graph updated from ‘Capital Accumulation: Fiction and Reality’:

Your aggregation of past retained earnings expressed in ‘real terms’ (R) is backward-looking, so regardless of its theoretical meaning, it’s unclear how it affects forward-looking capitalization.

On ‘real’ measures in economics, see for instance:

- ‘Price and Quantity Measurements: Theoretical Biases in Empirical Procedures’ (1989)

- Capital as Power (2009): Chs. 5 and 8

- ‘The Aggregation Problem: Implications for Ecological and Biophysical Economics’ (2019)

- ‘Real GDP: The Flawed Metric at the Heart of Macroeconomics’ (2019)

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

January 20, 2022 at 4:32 pm #247590

Jonathon writes “On an aggregate level, what capitalists buy with their profit is plant & equipment, or what economists call ‘real capital’ (buying other companies through mergers or acquisitions doesn’t alter the aggregate of what capitalists own, only redistributes it among them).”

But is it? In the trolley example the amount of capital connected with the trolley firms only manifested when they were destroyed. Similarly, when capitalists acquire other firms the price paid is typically more than the market value. The difference is known as goodwill. A significant fraction of of cumulative R consists of this goodwill that isn’t actually any sort of tangible thing, it certainly is not plant and equipment. It exists in the mind, but then so does culture (my take on the issue) or power (your take).

The key finding about R is that it works as a valuation tool (as does the power index). It also behaves like “that which when combined with people and resources produces output. This was shown by the correlation between GDPpc and R shown in my Jan 13 post. In fact, one can detrend per capita GDP by dividing by R. Two regimes can be seen. Over 1871-1907 and 1942-2006 this ratio ran in a fairly narrow range of 40-46. Between 1907 and 1942 and since 2006 the ratio declined dramatically indicating some sort of problem with how capitalism was operating. I call these periods capitalist crises.

I first saw this in 2010 and figured it was just an artifact. But after I learned about cliodynamics and secular cycles I was able to interpret it and wrote it up as a paper.

-

January 20, 2022 at 6:05 pm #247591

Thank you Alexander.

Regarding goodwill.

1. When company A acquires or merges with company B, the owners of company A pay for the assets of company B. The price they pay can be high or low, but the result is merely the transfer of the assets previously held by the owners of B to the owners of A. In this specific sense, mergers and acquisitions merely redistribute the ownership of existing assets.

2. The question you raise concerns the fact that acquired assets often rise in price relative to their per-acquisition stock market valuation (an increase that accountants usually attribute to the emergence of ‘goodwill’). This is a very real process, of course, but I’m not sure why it is an issue for your measure of R. As far as I understand it, R aggregates ‘real’ retained earnings, so when retained earnings are used to acquire ‘overpriced’ assets, the extra price due to goodwill — which is merely a polite way of saying greater power — should be eliminated when these retained earnings are deflated back to ‘real terms’.

Personally, I don’t think that ‘real-term’ measures have anything ‘real’ about them; I think that, conceptually, they are totally bogus. But you cannot hold both ends of the stick: if you measure retained earnings in ‘real terms’, then pure price changes should be eliminated. And if your price deflator cannot achieve this conversion, then the deflation process is invalid.

Regarding the aggregation of ‘real’ retained earnings over time.

I’m not sure what this measure tells us. If the Standard Oil of New Jersey retained $20 million of net earnings in 1890, and if this $20 million was used to pay for drilling equipment, train companies, bribed politicians and what not, how much of this equipment, material or immaterial as the case may be, is still a “resource” in 2022? Your method suggests that all of it is, and you argue further that you know its quantity in ‘real terms’. My opinion is that you cannot know either.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

January 21, 2022 at 3:25 pm #247595

Jon writes: I’m not sure what this measure tells us.

R provides a useful measure for capital. By this I means it serves a proxy for what “capital” needs to do. For example. capital, along with people and resources are a factor of production. Resources are consumed, their quantity does not affect output. If you double the size of the coal pile outside a power plant,you do not double the electrical output. On the other hand, capital and labor do affect the rate at which output is generated. Put a second generator in the power plant and you do increase the electrical output. Increase the number of installers and you can put more windows in. (We are having new windows installed and when asked how long it takes, they said all jobs take a day, they simply assign whatever number of installers necessary to get the job done in a day). Given these properties of workers and capital we expect that GDP should rise with population and have a special statistic, GDPpc, that we use to characterize growth in GDP independent of number of people. Thus, we should expect growth in GDPpc to reflect growth in capital, that is, capital accumulation.

The stock market is the capital market. Therefore, there should be a relation between the value of the stock market and the amount of capital. If we assume the S&P500 is a good proxy for the market as a whole, then the value of the index can serve as a measure of the amount of capital per share in the index.

R corresponds to both of these notions of what capital is.

[Jon] If the Standard Oil of New Jersey retained $20 million of net earnings in 1890, and if this $20 million was used to pay for drilling equipment, train companies, bribed politicians and what not, how much of this equipment, material or immaterial as the case may be, is still a “resource” in 2022?

None of it, as such. The money spent for the equipment is recovered by depreciation and so ceases to exist as a corporate asset on the books. The people trained/bribed are dead and so no trace of this still exists. The R created in 1890 was a resource in that year and measured at $20 million 1890 dollars ($540 million in 2020 dollars). The capital created by that investment is not associated with that equipment or training. It is the product of the increased sales (economic output) enabled by that investment. Those sales/output translate into increased income and a richer material environment resulting in a more complex culture that manifests as things like rising population-average IQ (Flynn effect).

[Jon] Your method suggests that all of it is, and you argue further that you know its quantity in ‘real terms’. My opinion is that you cannot know either.

The capital created by the investment in resources is preserved, the resources themselves are not. The former is part of the larger society, while the latter continues to belong to the company that made the original investment.

-

January 21, 2022 at 6:49 pm #247596

Thank you, Michael, for introducing your work and the useful dialogue.

We learn from disagreement.

-

-

January 22, 2022 at 8:06 pm #247606

Jon writes: I’m not sure what this measure tells us. R provides a useful measure for capital. By this I means it serves a proxy for what “capital” needs to do. For example. capital, along with people and resources are a factor of production. Resources are consumed, their quantity does not affect output. If you double the size of the coal pile outside a power plant,you do not double the electrical output. On the other hand, capital and labor do affect the rate at which output is generated. Put a second generator in the power plant and you do increase the electrical output. Increase the number of installers and you can put more windows in. (We are having new windows installed and when asked how long it takes, they said all jobs take a day, they simply assign whatever number of installers necessary to get the job done in a day). Given these properties of workers and capital we expect that GDP should rise with population and have a special statistic, GDPpc, that we use to characterize growth in GDP independent of number of people. Thus, we should expect growth in GDPpc to reflect growth in capital, that is, capital accumulation. The stock market is the capital market. Therefore, there should be a relation between the value of the stock market and the amount of capital. If we assume the S&P500 is a good proxy for the market as a whole, then the value of the index can serve as a measure of the amount of capital per share in the index. R corresponds to both of these notions of what capital is. [Jon] If the Standard Oil of New Jersey retained $20 million of net earnings in 1890, and if this $20 million was used to pay for drilling equipment, train companies, bribed politicians and what not, how much of this equipment, material or immaterial as the case may be, is still a “resource” in 2022? None of it, as such. The money spent for the equipment is recovered by depreciation and so ceases to exist as a corporate asset on the books. The people trained/bribed are dead and so no trace of this still exists. The R created in 1890 was a resource in that year and measured at $20 million 1890 dollars ($540 million in 2020 dollars). The capital created by that investment is not associated with that equipment or training. It is the product of the increased sales (economic output) enabled by that investment. Those sales/output translate into increased income and a richer material environment resulting in a more complex culture that manifests as things like rising population-average IQ (Flynn effect). [Jon] Your method suggests that all of it is, and you argue further that you know its quantity in ‘real terms’. My opinion is that you cannot know either. The capital created by the investment in resources is preserved, the resources themselves are not. The former is part of the larger society, while the latter continues to belong to the company that made the original investment.

CasP theory starts from the simple– and indisuptable– observation that capitalists price a financial asset by calculating the net present value of future income generated by that asset. This is the essence of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), which dominates finance. I don’t care whether the future income is unknowable (for bonds, it actually is known, at least nominally). Why? Because capitalists don’t care. If they did, they’d price financial assets differently.

Bichler and Nitzan did not create this reality. They don’t even argue that this reality is even a particularly good idea. They just accepted this reality is capitalism as understood by capitalists, and they used it to construct CasP theory.

Is there some reason you choose to ignore how capitalists price financial assets? Why isn’t their real capital your real capital?

-

January 23, 2022 at 7:59 pm #247610

Scott: Why isn’t their real capital your real capital?

I think it probably is.

Equation 11 in the CasP stock model paper provides a link between the power index (PI) and Hussman’s HMI:

1. HMI = PI * residual

Now HMI is Market capitalization divided by gross value added (GVA). Divide the top and bottom by the number of shares (N) and you get index value divided by GVA/N. R is an easy-to-calucate approximation for GVA/N. Hence HMI is very similar to P/R, similar enough that any differences will be covered by the residual. So we can write

2. P/R = PI * residual

So P/R and PI are functionally equivalent.

Using the long-term S&P500 earnings growth rate since 1940 of 6% and the long term stock market return of 10% for the risk-adjusted expected return from stocks as r we get

3. K = 25 E, where E is the current *trend* earnings.

This is a theoretical result and must be multiplied by H to obtain the current realized value of K, as manifested in the stock market (P):

4. P = K * H = (25 * E) * H

Now E the *trend* value of E, not the spot value. Robert Shiller introduced the CAPE index in the late 1990’s. CAPE is simply the index divided by the trailing 10yr average of earnings. That is, it is the trend value of E five years on the past. Given a 6% trend growth rate we relate the E in equation 3 to Shiller’s E (Es) as follows:

5. E = 1.06^5 * Es = 1.33 * Es

Substituting eq 5 into eq 4 gives

6. P = 33 * Es * H

From eq 4 and 6 we obtain:

7. K = 33 * Es

Since CAPE is P / Es we can also write

8. K = 33 * P / CAPE

Here P is the index value and CAPE is the Shiller valuation measure. Equation 7 says the true amount of capital is what stock investors think it is (P) adjusted for the amount of hype (measured using CAPE) present in the market. That is, it is the quotient of the index price and a valuation tool. P/R is a valuation tool just like CAPE (that what I designed it to do). Hence using my conceptualization, I would estimate K as the quotient of P and P/R, that is R.

In other words, the CasP definition of capital and R are the functionally the same. What is different is the interpretation of what K (or R) means. In CasP K is a measure of power. In my treatment it is a cultural element. Since “power” in the sense used in CasP is social/political/economic/philosophical in nature, all of which are cultural entities, power itself is an expression of culture.

As I formulate it, political instability, rising inequality, financialization, and financial crisis arise due to cultural forces and are interrelated. From cliodynamics I obtained a relation between the political stress index (PSI) introduced by Jack Goldstone in the 1990’s and modified by Peter Turchin as follows (from chapter 2 of my book):

A simplified expression for PSI is given below:

(2.1) PSI=e^2/(EF*(1-EF))

Here EF refers to the fraction of GDP that goes to elites (a measure of inequality), and e is elite number as a fraction of population. A simple relation to model elite number is given below.

(2.2) de/dt = μo (((1-EF)o)/(1-EF) – 1)

Here μo, and (1-EF)0 are adjustable constants. Between equations 2.1 and 2.2 the value of PSI can be obtained directly from inequality. PSI leads directly to instability as measured by frequency of instances of social unrest (e.g. riots, strikes, mass shootings, uprisings etc). If unchecked by policy to reduce inequality, it typically leads to extreme unrest in the form of civil war, revolution, invasion, state collapse, coup, etc.)

From cultural evolution I obtained a model in which I can obtain inequality from historical top tax rate and labor power as measured by strike frequency. From Hyman Minsky and modeling by Steve Keen, I obtain a qualitative model for financial instability in which risk of financial crisis is measured by a financial instability index (FSI) analogous to PSI. This conceptualization adds financial/economic collapse as another possible outcome of times like we are in today.

All of this results from political policy choices made by elites (which in modern societies are capitalist elites, but before about 3 centuries ago were other kinds of elites). Policy is the application of power, which today is capitalist power, so my formulation is in the end the same as CasP.

-

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.