Home › Forum › Political Economy › GameStop, hedge funds, and the “reality” of the stock market

- This topic has 10 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated March 2, 2021 at 2:44 pm by jmc.

-

CreatorTopic

-

January 29, 2021 at 1:59 pm #245232

Well, obviously, I want to hear everyone’s thoughts here on what’s been going on the last couple of days.

I’ve seen plenty of takes about how ridiculous it is that Robinhood and other brokerages have been able to simply shut retail investors out of trading these heavily-shorted stocks. And I’ve seen now that Citadel is all bound up in Robinhood. I’ve seen Leon Cooperman on CNBC crying the blues as I’ve seen others talk about this as some kind of revolutionary act. And, of course, I’ve seen leftist activists (misreading the room once again) in front of the NYSE asking for transactions to be taxed rather than picking up any kind of mantle relevant to the issue at hand.

What I’m most interested in, however, is the ongoing argument that I’ve seen now not just from Marxists but an increasingly wide swath of liberals and libertarians, that the stock market and the money in it is “fake.” I’d long felt the same way, but after reading CasP I began to believe that while it is certainly fantastical and in no way materially-contingent, the stock market and the power that it exerts over our productive capacities is quite real.

If that’s the case, how should one approach these conversations without sounding like a hedge fund capitalist oneself? My personal view, regardless of how “real” or “fake” it is, remains that the stock market should be entirely abolished. But anyway, I’m hoping to hear some CasP perspectives on the events of the past week, feel free to share anything.

- This topic was modified 5 years ago by Jeremy Zerbe.

- This topic was modified 5 years ago by Jeremy Zerbe.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

January 29, 2021 at 2:17 pm #245235

I just have time for a quick comment.

1. Calling the stock market ‘fake’ or ‘fictitious’ is a big mistake, because fake things aren’t supposed to impact the real world. And yet the stock market hugely impacts the social order.

2. I am still trying to come to grips with the recent events you mention. The best take I’ve read so far is by Cory Doctorow: https://pluralistic.net/2021/01/28/payment-for-order-flow/#wallstreetbets

Doctorow is a sci-fi fiction writer by trade, but offers very insightful commentary on political economy. I recommend following his blog.

3. I agree that we must ultimately abolish the stock market and replace it with a more democratic form of organizing. But I have no idea what that would look like.

-

January 29, 2021 at 4:21 pm #245236

Thank you Jeremy and Blair.

Capitalization is the ‘operational symbol’, to use Ulf Martin’s language, that creorders the capitalist mode of power. If this statement is correct, abolishing financial markets implies abolishing capitalism, or at least changing it so drastically that it becomes unrecognizable.

In the last section of our 2018 paper, ‘Theory and Praxis, Theory and Practice, Practical Theory’, titled ‘bridgehead’, we suggested one possible first step toward that end. It goes as follows:

[…]

Bridgehead

These considerations make praxis crucially dependent on fusing political action with ongoing empirical and theoretical research. To illustrate this necessity to know what we are doing, consider the following thought experiment. What if, instead of creordering the entire fabric of society, we start with a narrow bridgehead? Rather than trying to revolutionize the whole thing, we focus on one well-defined sphere. We inject into this sphere greater autonomy, cooperation and creativity, and then gradually tie these changes with, pull in and transform additional social spheres and processes, as well as our very understanding of society.

One promising site for such a bridgehead is the intersection of housing and pensions. The rapid urbanization of the planet makes affordable housing a key concern – and increasingly an impossible dream – for most wage earners. Similarly with pensions. According to the International Labour Organization, the vast majority of the world’s working-age population – up to 90 per cent – is not covered by pension schemes capable of providing adequate retirement income (Gillion et al. 2000). Left unattended, these trends are akin to social time-bombs. Used wisely, though, they might offer a leverage for autonomous social change around the world.

If we could come up with a democratically managed system that ploughs pension contributions into affordable housing and uses mortgage repayments and rent to pay pensioners, we might be able to align with and mobilize large chunks of society. And that’s just for starters. Affordable housing can be tied to sustainable urban planning, with creative architecture and new forms of public transportation to counteract and reverse the ecological devastation ushered in by uncontrollable sprawl. Those who live in autonomously developed urban areas and experience the democratic process might in turn wish to reform the educational system and broaden their self-government. The conceptual challenges created by a democratically managed pension-housing system might give rise to alternative accounting methods based on computations of public welfare rather than individual utility. Success in any of these areas could spill over into other areas of society, while failure would encourage rethinking and exploring of alternative routes. What started as a mere bridgehead could gradually expand into a broad creordering of society at large.

Can this thought experiment be translated into praxis? Perhaps – but only if we are able to conceive, develop and implement it in conjunction with ongoing empirical and theoretical research.

There are three related reasons for this requirement. One is that the changes outlined above constitute a direct assault on the capitalist mode of power: to democratize housing is to undermine the concentration of private real-estate ownership and management; to withdraw pension funds from the stock market is to arrest asset-price inflation and deprive capitalists of the nearly total leverage they have over middle-class incomes and the middle-class way of life; to demonstrate the efficacy of self-management in more and more realms of society is to delegitimize the sanctity of private enterprise and sound the death knell for accumulation.

So dominant capital and its power belt of government officials, economists and public-opinion makers are bound to fight this process nail and tooth. They will dismiss its underpinnings and attack its supporters. They will thwart its planning and sabotage its implementation. They will use sticks and carrots, brainwashing and threats, persuasion and violence. There is no way for us to withstand, resist and overcome these attacks without understanding – in general and in detail – the power logic they obey and the power structures they mobilize. And that understanding requires relentless, in-depth research.

Another reason is that even if we succeed and see our bridgehead gaining traction and spreading into other areas of society, initially these areas will have to coexist and interact with parallel structures of capitalist power. To put this parallelism in context, note that the modern capitalist principles of investment and accounting, discounting and finance and wage labour and increasing efficiency emerged in the early part of the second millennium AD, but that until very recently – perhaps as late as the nineteenth century – they operated within and alongside the logic of feudalism. And if that proves to be the case with post-capitalist alternatives, our praxis will depend crucially on understanding the ever-changing dynamics of capitalist power in which these alternatives exist.

Last but not least, enfolding research with praxis could boost the morale and optimism of progressive groups around the world. To show that democratic schemes such as pension-supported housing can actually work – i.e., that they serve the autonomy and wellbeing of their members while weakening the power logic of capital – is to demonstrate that we understand capitalism and can do better; that alternatives to capitalism can be imagined, planned and implemented.

This understanding, however, is difficult if not impossible to gain when we embrace academic dogma, cling to outdated political slogans and shun empirical research. The only way to achieve it – certainly on any meaningful scale – is through a series of autonomous, non-academic research institutes that are informed by and cater to societal action. These are not mere sidekicks. In our complex world, they have become a prerequisite for effective praxis.

-

January 29, 2021 at 6:07 pm #245237

Remember when BitCoin’s price soared? Everybody jumped on the story, and if you listened to the predictions of certain circles, we would all soon be buying groceries and paying rent with de-centralized currency.

That is what is striking me with the reporting on the GameStop price jump. I don’t have a clear answer right now, but it is wild to see what people are already saying about the effect of the event on the future of Wall Street or even of capitalism.

My thoughts that people are jumping feet first into the “rebelliousness” of reddit’s behavior were confirmed when YouTube recommended to me Joe Rogan’s thoughts about it on his podcast. Because that is what I was thinking: “What does Joe Rogan think about this mess?!?”

-

January 30, 2021 at 11:19 am #245240

Market tops are congested with hype-laden fanfare and scandals, which is where the ‘shoe shining boy’ theory of financial investment kicks in.

The theory, which many an exist-in-time mogul claim their own, posits that when you start getting investment tips from shoe-shiners and other folks who normally just work for a living, it’s time to sell your equity holdings.

-

January 30, 2021 at 10:45 pm #245241

One aspect of the GameStop story is definitely relevant to the CasP approach: the question of what the high market value of GameStop is resting on. Can we say GameStop is overvalued but without falling into the trappings of the real-nominal dichotomy?

Hopefully we find a method to integrate the old forum with the new one. In the meantime, readers can see that this issue has come up before, in the context of speaking about ‘bubbles’ in the stock market.

- This reply was modified 5 years ago by jmc.

-

January 31, 2021 at 10:37 am #245246

The question is what do stock prices ‘represent’?

According to Keynes, in his General Theory, the answer is a differential guess about what others think they represent:

This tongue-in-cheek seems reasonable a description for short-term investment and for particular stocks, but over the longer term and for broad aggregates, investors price stocks by discounting risk-adjusted expected future earnings. In most cases, prices correlate positively with earnings expectations, and negatively with risk perceptions and the normal rate of return. The correlations themselves — particularly between prices and earnings — can change over time (see Figures 7 in our CasP Model of the Stock Market), but they tend to be positive.

From a capitalization perspective, terms such as ‘manias’, ‘bubbles’ and ‘irrational exuberance’ represent excessive profit expectations — or rising ‘hype’. Of course, most frenzied investors who buy into these upswings don’t think of future earnings. They follow Keynes’ narrative. But in their actions they drive up – and are further driven by — the hype.

- This reply was modified 5 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

February 5, 2021 at 2:10 pm #245280

I have posted Tim Di Muzio’s commentary on the GameStop phenomenon. Worth a read:

GameStop Capitalism: Wall Street vs. The Reddit Rally (Part 1)

-

February 26, 2021 at 3:48 pm #245393

Thank you Blair for sharing those pieces from Doctorow (love him) and Di Muzio, and thank you Jonathan for sharing that bit from your 2018 paper, which I ended up reading in full—and serendipitously so, because I’ve been thinking a lot lately about CasP with regard to both class and praxis. It’s given me much more than just this issue to think about, which I’m sure I’ll return to at some point in a new post here in the forum.

Doctorow’s post was (as ever) very clarifying, but I found Di Muzio’s opinion overly rosy. After all, as B&N’s bridgehead identifies, any truly revolutionary practice within the realm of finance would need to remove money from the power brokers and their market casino and instead plough it into democratically-controlled real assets such as affordable housing if we wish to undermine and delegitimize private ownership and enterprise. While I certainly was rooting for even the richest of these retail investors to knock a hedge fund down a peg, playing within the game is just that: taking a seat at the casino table. It’s not exactly a count-room heist, nor is it burning down the casino. Especially as the $GME price has once again leveled (albeit higher than before), it’s hard to see the events that played out as anything more than a fun news cycle or two before the casino bosses brought everything under control once more.

If the surge from r/WallStreetBets shows us anything about capital as the “organized power of a firm to shape and reshape the terrain of social reproduction,” it’s that while ad hoc “firms” of like-minded and like-intentioned individuals can, with enough organization, affect some degree of change for some amount of time, their ability to actually upset an established feature of capitalist society is, of course, extremely limited. The stock market is the very center of value creation and capitalist power, and so it was always going to be tough for a bunch of people on Reddit to make something stick. Nor was this ever really their intention.

This brings me to B&N’s bridgehead. I think the pension-housing idea contained within is a useful one, a smart one even, and I recognize that the whole point being made is that research must be done to develop other, interconnected plans and to show how they are viable. However, the concept runs aground in the same place as the $GME short surge for me.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of total US workers participating in pension plans in 2018 was only 21%, while a mere 12% of private-sector workers do so. Retirement savings plans like 401(k)s, on the other hand, are contributed to by 43% and 47% of workers, respectively. Even a massive movement of pension money toward a revolutionary financial project like that suggested would be frightfully insignificant. And that is without even considering the proportion of workers who can actually control where those funds go through some means of workplace democracy. The most substantial amount of the pensioned work in state and local governments (comprising just 19 million of the US’s total 139 million workers). There, 76% of workers participate in pensions compared to a scant 17% who contribute to 401(k)s.

Perhaps, then, this small but focused sector is the lodgment of the bridgehead. To make progress here, however, would likely mean making this an investment project of the state, or at least the continually-beleaguered public sector unions. Public banking might provide a solution, but while that issue has become one around which socialist debt and finance discourse and action increasingly revolves, it’s beset by the same issues and interests that this bridgehead is. After all, these are by no means lucrative propositions, and while the existing solutions are, we can all agree, inadequate, they are still, for most people, sadly good enough—at least in their own estimations. As a friend I shared this bridgehead proposal with said:

That sounds nice but I don’t know how you convince people to agree to drastically reduce the returns on their pensions and consequently their ability to retire.

The left has to have a better offering to people than the people with capital do. They’re offering huge percentages of wealth increase (relatively) to those who have money to invest or pension plans, in exchange for making the wealthy drastically wealthier. The left answer can’t be “We’ll make you less wealthy but you’ll help people even worse off than you,” if you want to get people to actually do this.

Outside of taking money from the richest of the rich, we’re hurting people who don’t have enough to help people with even less.

How, then, to break the “nearly total leverage [capitalists] have over middle-class incomes and the middle-class way of life” when middle-class disinterest is as hostile to change as the oppositional interests are? How to get people to resist the possibilities of the casino table even when the realities of the game being played are so fraught and winnings ever worsening? How to develop organized social power great enough to begin to create a new kind of society without the requisite capital flow (let alone accumulated capital) to creorder it?

There seem to be a great number of carts to put in order here, and no horse in sight.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 11 months ago by Jeremy Zerbe.

-

March 1, 2021 at 10:04 pm #245396

Hi Jeremy:

1.

The percentage of pension ‘coverage’ per se does not tell us the $ size of pension assets saved by different groups.

Here is a table from the U.S. Survey of Consumer Finance, showing the size of retirement accounts by percentile of net worth:

The table suggests that, in 2019, the bottom half of the population has very small retirement account saving: the poorest 25% of households have $4,700 per family, and the next 25% have $19,000 per family. The next 25% have more, but scarcely enough to retire. These savings have risen only marginally over the past 20 years.

2.

Regarding the use of higher returns to lure the underlying population away from the stock market. The vast majority of those who would join such a project are not “invested” in the stock market, certainly not in a meaningful way (you can verify it by looking at the tables offered by the Survey of Consumer Finance). And the attractiveness of the bridgehead program, I think, is not its differential rate of return, but the housing and retirement security it offers and the participation in shaping one’s own life.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 11 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

March 2, 2021 at 2:44 pm #245399

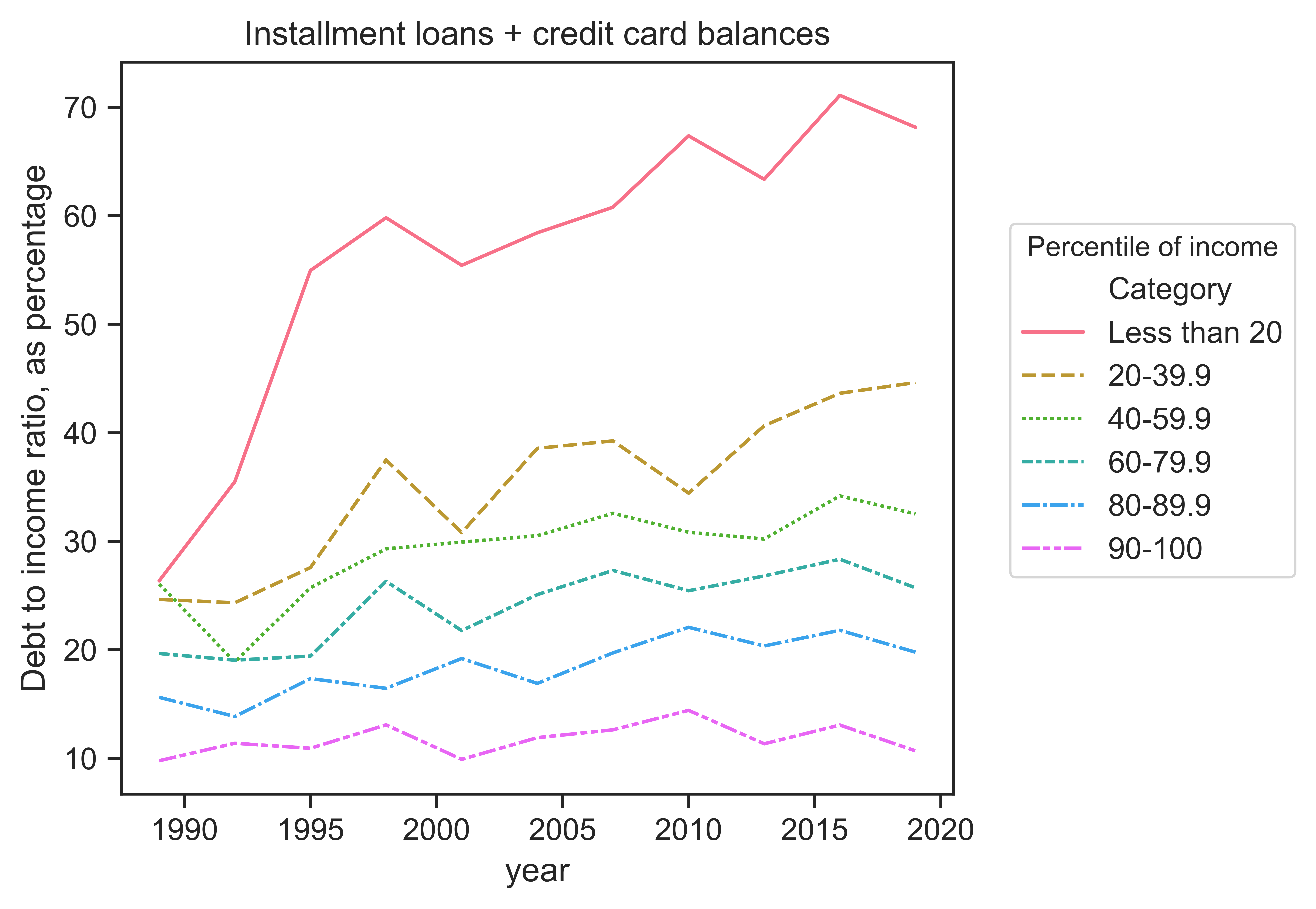

That link is great, Jonathan. The breakdown of consumer finance by percentiles of income or wealth can help dispel assumptions about our collective investment in capitalist systems of retirement or debt. For example, I curiously plotted the ratio of credit card and installment debt to income. The impact of this type of debt is far from evenly distributed across income bands. Moreover, this debt is difficult to get out of through asset liquidation; often the things we buy on credit cards and installment plans (cars) depreciate in value.

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.