- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated December 10, 2022 at 10:36 pm by .

-

Topic

-

1.

Neoclassical economists measure accumulation by the growth of the ‘real’ capital stock.

The problem is that the capital goods comprising this stock lack a common denominator (try adding the ‘real’ magnitude of 20 oil rigs with that of 30 automotive factories). The neoclassicists bypass this difficulty by making three assumptions that national account statisticians then happily apply. They stipulate that

(i) the ‘real’ quantity of capital goods represents their util-generating capacity;

(ii) in a perfectly competitive equilibrium, relative quantities are proportionate to relative prices (so if an automotive factory costs twice as much as an oil rig it must possess twice the util-generating quantity); and

(iii) they can spot this equilibrium when they see it and use its relative prices as relative weights with which to aggregate the underlying capital goods.

Unfortunately, nobody has ever shown these assumptions to be valid, and until someone does, the computations they give rise to remain arbitrary to an unknowable extent.

To illustrate this arbitrariness, consider the chart below, taken from Page 131 of Capital as Power. The two bottom series count the number of automotive factories and oil rigs, while the top two series measure their aggregate ‘real’ quantity under different conditions.

The figure shows how changing the equilibrium year from 1970 to 1974 alters the relative prices and therefore weights of automotive factories and oil rigs, causing the same collection of automotive factories and oil rigs to have more than one quantity.

Since perfectly competitive equilibrium — even if it exists — is forever unknown, we can take, as national account statisticians routinely do, any pair of prices, assume it is associated with a perfectly competitive equilibrium, and end up with any number of ‘real’ quantities for the same capital stock – and all that without having any way of knowing which of these quantities is ‘correct’!

2.

Marxists measure the accumulation of capital by the growth of the socially necessary abstract labour time, or SNALT, required to reproduce that capital. However, SNALT is rather difficult if not impossible to measure due to a slew of theoretical roadblocks (Capital as Power, Chs. 6-8). Consequently, Marxists either guess it indirectly, by mixing money prices and wages with various assumptions about what constitutes ‘productive’ labour (as opposed to ‘unproductive’ labour that presumably does not generate surplus value), or simply use the ‘real’ capital stock, courtesy of the neoclassical national accounts.

3.

CasP sees capital as a form of power and therefore conceives its accumulation not absolutely, but differentially. Also, unlike neoclassicists and Marxists, CasP views capital as forward-looking capitalization of risk-adjusted expected future earnings rather than as backward-looking material/productive capital stock – a crucial difference, since the nominal growth rates of these two magnitudes, as least in the U.S., are inversely correlated (see Figure 1 in this invited-then-rejected interview).

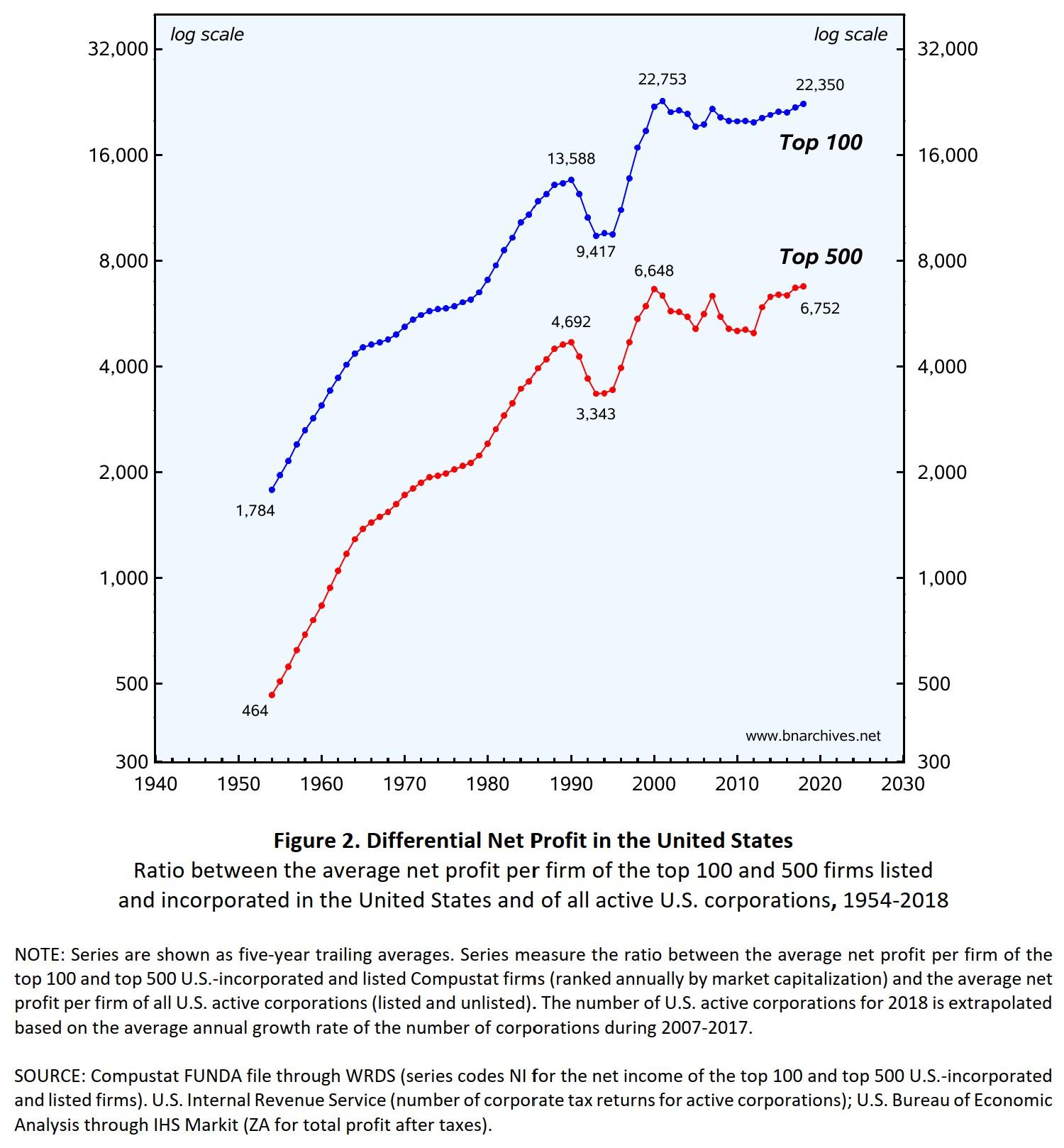

In the figure below, taken from our 2021 paper ‘Dominant Capital is Much More Powerful Than You Think’, we compute the ratio between the average net profit of U.S. dominant capital — the top 100 and 500 corporations based and listed in the U.S. — and the average net profit of all U.S. corporation (in this chart, we use net profit rather than market capitalization because the vast majority of corporations are unlisted and therefore don’t have readily observable market values).

In our view, the resulting ratio, which is a pure number, represents neither utils nor SNALT, but the relative power of dominant capital. Over the long run, the rate of change of this ratio (read power) proxies the rate of differential accumulation.

Note that this differential represents only the quantitative side of capital as power. The other, qualitative side comprises the various ways in which the power of dominant capital is manifested through sabotage, and one purpose of CasP is to contrast, theorize and research their correspondence (for a 2018 survey of this quantitative-qualitative analysis, see ‘The CasP Project: Past, Present, Future’).

4.

This broad-brush overview suggests important differences and incompatibilities between the neoclassical, Marxist and CasP notions of accumulation.

The neoclassicists lack an objective unit of capital, even by their own standard. The Marxists claim to have an objective measure, but various theoretical considerations, along with their practice of using the neoclassical measure or money prices adjusted by arbitrary assumptions, suggest otherwise. CasP measures of accumulation are denominated in prices and are readily observable.

However, because CasP views the entity of capital not absolutely but differentially, and because it focuses on forward-looking finance rather than backward-looking means of production, the accumulation process it describes is very different from the one depicted by both neoclassicists and Marxists.

5.

In the neoclassical and Marxist methods, power is mostly if not inherently external to capital: it either distorts capital accumulation (in the neoclassical case) or aids it (in the Marxist case), but both effects are assumed exogenous. In CasP, power is internal to capital: power defines the end goal of accumulation as well as the method and process by which this goal materializes.

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.