- This topic has 1 reply, 2 voices, and was last updated October 19, 2022 at 10:22 pm by .

-

Topic

-

Here is an interesting question about capital as power from Guy Tal (Twitter thread: https://twitter.com/guytal10/status/1582666152064344064)

Isn’t there a danger of transforming this argument [capital as power] into a mirror of the util theory? If capitalists only care about the effect a certain asset has on capitalization, and since capitalization is differential power…

Couldn’t we say that this power is virtually the ability to sabotage society’s welfare through prohibiting this asset’s use? And that wouldn’t be just the mirror of the asset’s possibly contribution to society?

Then in order to specify the material foundation of this power (the ability to wreck sabotage and affect society mediated by ownership over ideas and materials) we eventually restore similar problems of mainstream economics?

In CasP:

1. capitalization = (future earnings x hype) / (risk / normal rate of return)

And:

2. differential capitalization = (differential future earnings x differential hype) / differential risk

My understanding of Guy’s argument is that, if the elements on the right-hand side of Equation 2 are determined by various forms of sabotage, then the overall effect of this sabotage, reflected in differential capitalization, is in fact an inverse proxy for the forgone utility to society of the sabotaged entities/processes/institutions. The greater/lesser the utility of the sabotaged item, the greater/lesser the differential capitalization of the saboteurs.

Is this argument valid?

I’d say that the answer is a tiny yes and a very big no.

THE TINY YES. In the aggregate, for sabotage to generate capitalist earnings and hype and to reduce risk it must be applied to something that is ‘useful’ to society (I prefer to expunge the neoclassical term ‘utility’, whose meaning and quantity are forever unknowable). Thus, sabotaging or threatening to sabotage the overall level of oil production, the general application of food-growing technology, cultural creativity, or freedom of movement is likely to affect the overall level of capitalist income, hype and risk. But this loose association does not imply that capitalization in general and differential capitalization in particular are inverse proxies for society’s wellbeing. The key reasons are as follows.

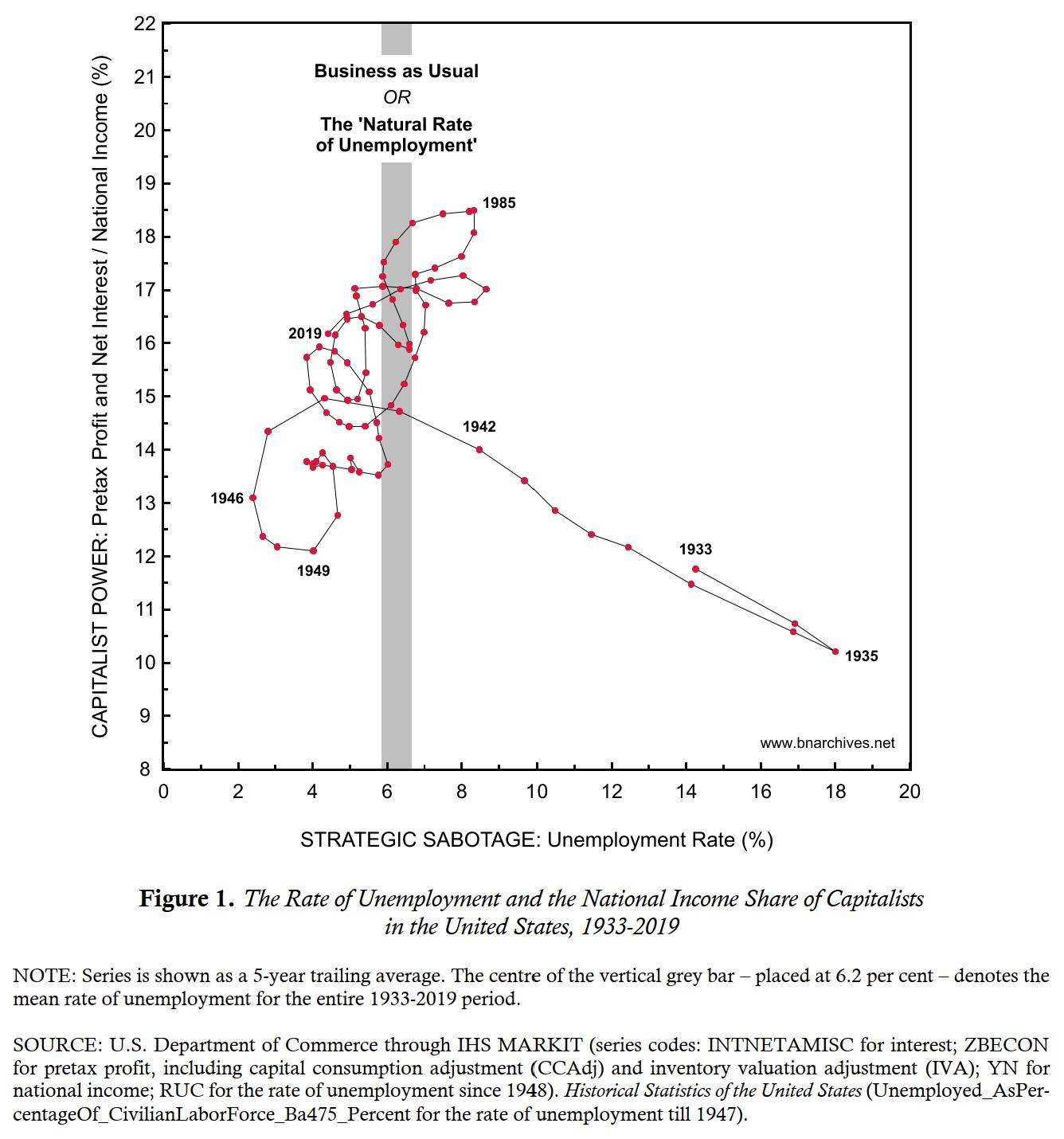

THE BIG NO (1): The connection between sabotage and capitalization is nonlinear: too much or too little sabotage are likely to undermine capitalization. This nonlinearity is why, following Veblen, we speak not of sabotage but of ‘strategic sabotage’. In the U.S. chart below, for example, we see that unemployment, a general form of sabotage, relates to the capitalist share of national income, but that the relationship is nonlinear (https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/663/). And this nonlinearity means that the same capitalist share of national income (for example, 13%) can be related with more than one level of sabotage (in this case, with unemployment rates of 2.5% and 10%). In other words, knowing the capitalist share of national income tells us little or nothing about the lost wellbeing of forgone employment.

THE BIG NO (2): A given level of sabotage need not translate to a unique level of earnings/hype/risk, let alone to unique differential magnitudes for these variables. For example, in our work we found that Middle-East Energy Conflicts tend to boost the differential rates of return of the Petro Core (leading oil companies) – but as this chart shows, the magnitude of this effect varies greatly across conflicts. So here, too, knowing the differential consequences of sabotage tells us very little about the wellbeing they presumably sabotage.

THE BIG NO (3): In the capitalist mode of power, ‘wellbeing’ is not some externally given entity, but a constructed imposition that conditions people to accept specific notions of necessity and desirability (think: junk food, debilitating entertainment, urban sprawl, private transportation, overmedication, advertisement, patriotism, private=good/public=bad, etc.). In our view, this imposition of ‘preferences’ is a major form of sabotage. And, if we are right in this claim, then when capitalists threaten to withdraw access to these imposed preferences, they are not limiting wellbeing, but augmenting their own sabotage…

So, I’d say that, all in all, the capitalized consequences of sabotage cannot be considered the inverse of social wellbeing, let alone of neoclassical utility.

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.