Home › Forum › Political Economy › Is “Hype” Really an Elementary Particle of Capitalization?

- This topic has 13 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated December 10, 2021 at 3:48 pm by Scot Griffin.

-

CreatorTopic

-

December 6, 2021 at 5:34 pm #247296

Personally, I’ve never seen any Wall Street analyst include a “hype” factor in their discounted cash flow analyses of future earnings. Perhaps one could argue that “hype” determines earnings growth projections, but those are typically explicitly stated or shown, usually are based on recent earnings growth, and typically taper down to some lower, terminal growth value that is used to calculate a terminal value of the earnings. I have seen stocks (e.g., Tesla and, previously, Amazon) that seem wildly over-valued compared to fundamentals, and that phenomenon is of interest, but over time an overvalued stock can to an undervalued stock, and vice versa. (Let’s be clear here, I don’t believe in the accuracy or validity of analyses that claim to measure the present value of something that may never exist, so I am using the terms undervalued and overvalued in a relative, not absolute, sense.)

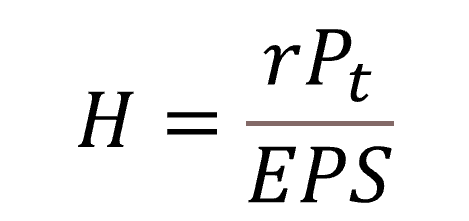

My larger concern is that “hype,” like utils, snalts and “capital stock” cannot be definitively measured. For example, how does one, ex post, measure error in expected future earnings that run to the end of time? Especially as capitalization (Kt), price (Pt) and earnings per share (EPS) can (and usually do) change over time? Using equation 4 to solve for H, H = (rPt/EPS), you can establish the value of H at the time a share is purchased, but there’s no reason to expect H to remain constant over time, even if r is held constant (which it isn’t), Pt/EPS doesn’t remain constant (see prior discussions regarding the “Systemic Fear Index”).

Anyway, I understand that “hype” plays a minor role in CasP theory, but CasP authors still refer to it from time to time, and I think it just opens up CasP to the same type of criticisms that CasP levels at mainstream and Marxist economics. Regardless, the concept of “hype” does not seem to add any value to CasP in a broad sense, although it might when focused on specific stocks that seem particularly inflated or deflated from a nominal expected value. In that kind of case, “hype” may really be a conscious manifestation of power, i.e., dominant capital is rewarding (or discouraging) a particular company to encourage (or discourage) greenfield investment in competitors.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

December 7, 2021 at 5:03 am #247297

Hi Scot,

Your post really made me think, because I have very little experience in this arena. So I had to do a little digging to refamiliarize myself with the concepts being addressed.

My larger concern is that “hype,” like utils, snalts and “capital stock” cannot be definitively measured.

I think that part of the point made in CasP, is that none of it is really measurable in the absolute sense. That’s half the point. By hyping future earnings prior to earnings calls, the investors are then steered toward a desired share price.

Personally, I’ve never seen any Wall Street analyst include a “hype” factor in their discounted cash flow analyses of future earnings.

The way I understood it, Hype wasn’t something that could be seen in individual company data in the short term, and could only be identified in the long view because of the dramatic over/under estimation of value reflected in the Hype Index vs Expected Earnings Share data presented in the book. And it isn’t visible at the individual analyst level, because the analysts are all following each other’s lead, so to speak.

Perhaps one could argue that “hype” determines earnings growth projections, but those are typically explicitly stated or shown, usually are based on recent earnings growth, and typically taper down to some lower, terminal growth value that is used to calculate a terminal value of the earnings. I have seen stocks (e.g., Tesla and, previously, Amazon) that seem wildly over-valued compared to fundamentals, and that phenomenon is of interest, but over time an overvalued stock can to an undervalued stock, and vice versa.

This sounds like a decent enough summation of what is described in the book. It is not that Hype sets the price, but that it influences investors/shareholders in order to guide them toward a desired price.

Regardless, the concept of “hype” does not seem to add any value to CasP in a broad sense

I have to disagree, based on my admittedly limited understanding. If the herd mentality of Analysts is demonstrable (as seen in the above chart), then this provides a frame of reference with which to approach investigation of hype at a more granular level

although it might when focused on specific stocks that seem particularly inflated or deflated from a nominal expected value. In that kind of case, “hype” may really be a conscious manifestation of power, i.e., dominant capital is rewarding (or discouraging) a particular company to encourage (or discourage) greenfield investment in competitors.

So if we can (hesitantly) classify Hype into 2 categories, Generalized, and Granular. Then we can focus down to see the agency behind Granular Hype. Generalized Hype becomes a Particle of Capitalization as viewed at the overall market level, while granular hype can be described more closely as a concept of power (COP). A mechanism for the pulling of strings.

This is where it becomes important to know the actual power players in the game, and once identified, we can then apply the CasP framework to the Power Players overall strategies and tactics for a clearer understanding of individual motivations. But I don’t think that the CasP framework is that clearly refined as yet, before the framework can be applied at such a level, we would need a comprehensive understanding of most, if not all, of the Concepts of Power being deployed throughout the Capital Power regime. And so far, I don’t think we have even gotten a comprehensive list of COPs, let alone a detailed analysis of their individual or collective effects.

-

December 8, 2021 at 12:59 am #247305

Thanks for your thoughtful response, Pieter. You helped me to better understand your point of view about “hype,” which appears consistent with Jonathan’s, but, as you can see from my response to Jonathan, understanding does not equal agreement.

In the law, I was taught that you sometimes need to sacrifice precision for clarity, but as someone also trained as an electrical engineer I have difficulty applying the same lesson to what is supposed to be science. Pedantry is a feature of science, not a bug.

–Scot

-

-

December 7, 2021 at 8:08 pm #247298

Thank you Scot and Pieter.

1. Can hype be observed/measured?

Hype = EE / future earnings

We can observe expected earnings EE by asking those who expect them what they expect. In retrospect, we can know what the future earnings (E) turned out to be. By dividing one by the other, we get Hype.

In practice, this computations can be complicated because we have to ask everyone who expects and collect eventual earnings data, but these are practical rather than conceptual difficulties. Backward measuring ‘earnings all the way to eternity’ is of course impossible since eternity is never reached, but earnings over the past 100 or 200 years can be measured — and that should do, since discounting reduces the significance of more distant observations.

So no, hype isn’t like utils and SNALT. It can be measured, unambiguously, in principle; and, with enough resources, it can also be measured in practice.

2. Is hype important?

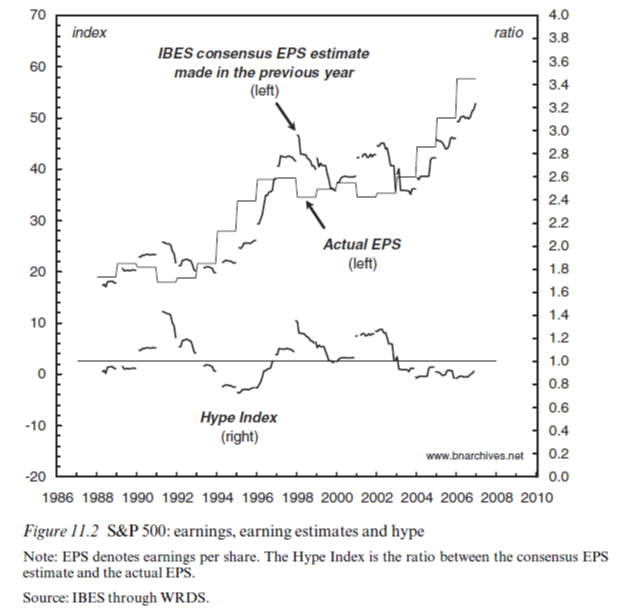

We think it is. The example we give in Figure 11.2 of our book shows that the two-year earnings projections of analysts contain very large errors, and that these errors tend to be systematic and herd-like. Think of what the errors might be for 10-, 50-, or 100-year projections. The key point is that these large ‘errors’ are often leveraged and indeed creordered by dominant capital, and in premeditated ways, and they often have significant consequences for society (think of the roaring twenties turning into the Great Depression and WWII, or of the dot-com and subprime crises having set the stage for the current global turmoil.)

3. What do we know about the power underpinnings/consequences of hype?

Right now, scarcely anything, so it is hard to determine how important it is and in what ways. But that is always the case with new, unexplored ideas. The only way to know is to research them.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

December 8, 2021 at 12:34 am #247303

Thank you Scot and Pieter. 1. Can hype be observed/measured? Hype = EE / future earnings We can observe expected earnings EE by asking those who expect them what they expect. In retrospect, we can know what the future earnings (E) turned out to be. By dividing one by the other, we get Hype. In practice, this computations can be complicated because we have to ask everyone who expects and collect eventual earnings data, but these are practical rather than conceptual difficulties. Backward measuring ‘earnings all the way to eternity’ is of course impossible since eternity is never reached, but earnings over the past 100 or 200 years can be measured — and that should do, since discounting reduces the significance of more distant observations. So no, hype isn’t like utils and SNALT. It can be measured, unambiguously, in principle; and, with enough resources, it can also be measured in practice.

But the future earnings (E) of Equations 1 and 3 of the book (CasP 2009) is asserted as representing ALL future earnings in perpetuity, which we have yet to (and cannot possibly) measure because they have not come into being yet. Interestingly, the trend line of the EE/actual ratio (aka the Hype Index of Figure 11.2 of the book) over time, on average, appears nearly equal to 1.0, which implies accuracy, not error (I think?).

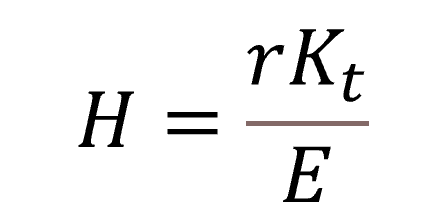

In any event, according to equation 3 of the book, H = rKt/E, and according to equation 4 of the book, H=rPt/EPS.

The “Hype Index,” or EE/”actual” future earnings, does not measure Kt, so it says nothing about H according to equation 3 of the book.

On the other hand, you have measured Pt/EPS as part of constructing what you call the “Systemic Fear Index,” which focuses on the correlation between P and EPS. Perhaps the common explanation for “Hype” and “Systemic Fear” is confidence in obedience, i.e., power itself? If so, do we need “hype” as a separate concept?

FYI – I have been tearing apart the “capitalization” methodology of one value investor pay-site with the intent of publishing their methodology as compared to CasP’s version of capitalization. The site’s primary goal is to determine whether a stock is undervalued or overvalued, i.e., the site’s goal is to identify stocks whose price objectively does not make sense. Thus, instead of creating “hype,” the straightforward application of free cash flow “capitalization” models can identify the presence of “hype,” which means that hype is not an elementary particle of capitalization but is exogenous to it.

2. Is hype important? We think it is. The example we give in Figure 11.2 of our book shows that the two-year earnings projections of analysts contain very large errors, and that these errors tend to be systematic and herd-like. Think of what the errors might be for 10-, 50-, or 100-year projections. The key point is that these large ‘errors’ are often leveraged and indeed creordered by dominant capital, and in premeditated ways, and they often have significant consequences for society (think of the roaring twenties turning into the Great Depression and WWII, or of the dot-com and subprime crises having set the stage for the current global turmoil.)

The fact that all earnings forecasts start with the same data regarding prior earnings and growth makes it easy, in hindsight, to misidentify earnings forecasts as “herd behavior.” People applying the same mathematical models to the same data with slightly varying assumptions (where judgment is allowed) are going to reach similar conclusions. The real question is why do these mathematical models exist?

We know, for example, that CAPM is complete junk, and yet it is central to the valuation approaches of at least 70% of all analysts. How and why is that?

Modern Finance has essentially introduced the institutional and systemic biases of dominant capital into how we understand Finance, capital, and the world, generally. In this sense, “hype” is a vector, not a scalar, and it is universal and not limited to the ritual of capitalization. The biases of dominant capital have both a magnitude and a direction, but the term “hype” implies ideas like “herd mentality” and “mania,” which obscure the real problem and prevent us from identifying capital’s biases, let alone measuring their magnitude or direction.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Scot Griffin.

-

December 8, 2021 at 3:51 pm #247309

Modern Finance has essentially introduced the institutional and systemic biases of dominant capital into how we understand Finance, capital, and the world, generally. In this sense, “hype” is a vector, not a scalar, and it is universal and not limited to the ritual of capitalization. The biases of dominant capital have both a magnitude and a direction, but the term “hype” implies ideas like “herd mentality” and “mania,” which obscure the real problem and prevent us from identifying capital’s biases, let alone measuring their magnitude or direction.

I might be misreading this, but is the relevance of hype dependent on whether it is only a ritual internal to a dominant group of capitalists?

If dominant capitalists can differentially accummulate by stirring up herd mentality with such tactics as overly-optimistic earnings expectations, I might misunderstand the concern with hype being employable by any and all. If the root of hype is social-psychological, the ability to oversell with optimism or downplay with pessimism is universal — and certainly has a social origin before the Italian Renaissance and the bourgs. Yet, power is the root of a dominant class scaling the effects of hype, much in the same way that risk is not an exclusive concern of dominant capital.

-

December 8, 2021 at 5:15 pm #247314

Modern Finance has essentially introduced the institutional and systemic biases of dominant capital into how we understand Finance, capital, and the world, generally. In this sense, “hype” is a vector, not a scalar, and it is universal and not limited to the ritual of capitalization. The biases of dominant capital have both a magnitude and a direction, but the term “hype” implies ideas like “herd mentality” and “mania,” which obscure the real problem and prevent us from identifying capital’s biases, let alone measuring their magnitude or direction.

I might be misreading this, but is the relevance of hype dependent on whether it is only a ritual internal to a dominant group of capitalists? If dominant capitalists can differentially accummulate by stirring up herd mentality with such tactics as overly-optimistic earnings expectations, I might misunderstand the concern with hype being employable by any and all. If the root of hype is social-psychological, the ability to oversell with optimism or downplay with pessimism is universal — and certainly has a social origin before the Italian Renaissance and the bourgs. Yet, power is the root of a dominant class scaling the effects of hype, much in the same way that risk is not an exclusive concern of dominant capital.

I am questioning whether “hype” is even a thing. Certainly, I don’t believe hype is an “elementary particle” of capitalization, as asserted in CasP 2009, nor do I think hype as discussed in equations 3 and 4 is measurable, even though the “Hype Index” of Figure 11.2 of CasP 2009 claims to measure it in a way not suggested by either equation. To me, the closest thing that’s been done to measuring “hype” in the manner suggested by equation 4 of the book is the “Systemic Fear Index,” which suggests to me that perhaps “fear” and “hype” are two sides of the same confidence coin, that maybe what we are better off forgetting about “hype” and “systemic fear” and thinking directly in terms of measuring confidence, as power is confidence in obedience.

Jonathan and Pieter have convinced me that my view of “hype” may be too narrow, that I need to look beyond equations 3 and 4 and to what they see as effects of “hype,” however defined, such as herd mentality, etc., to understand whether the concept of hype is useful in understanding capital as power (and, clearly, I may be the only one questioning the value of hype, as defined in the book, to CasP analysis). So, in the quote above, I was thinking out loud about the possibility that “hype” is better viewed as a broad and pervasive assertion of power that shapes our understanding of the world. This is in-line with, and perhaps inspired by, my understanding of the origins of neoliberalism and the tactics neoliberals engaged in to make it safe to be a capitalist again.

I am reminded of the book The Mismeasure of Woman by Carol Tavris, which made the argument that culturally and historically, the measuring stick for women has been men. When “man is the measure of all things,” woman is forever trying to measure up. Using the white, Christian straight male as the metric for normalcy has generally been beneficial to all white males, but has not necessarily been good for everyone else (see, e.g., what many call “white privilege”).

Is it possible that dominant capital (or capitalists generally) have managed to establish pro-capital biases/metrics that we don’t even recognize as such, biases/metrics that we apply unthinkingly because they are embedded in how we have been conditioned to think? Again, I think the free cash flow valuation models compel what we view, in hindsight, as herd mentality, but the math is the math and has no mentality. If there is any herd mentality, it is in the commonly held but mistaken belief that the future is reliability knowable. What about the things we don’t measure, is there a reason for that? In the capitalist world, they like to say “if you can’t measure it, it doesn’t exist,” so have we been conditioned to not measure or overlook things that make capitalists uncomfortable?

This type of thinking is what led me to suggest that “hype” may be better understood as a set of pro-capital biases/metrics that are not only institutional, but internalized in everyone who is a member of a capitalist society. I don’t know if the right term is “social-psychological” because the phenomenon seems deeper and broader than that. These are things we all know and believe, sometimes without recognizing that we do, because of the culture we live in. It is more than propaganda or puffery (what I think of when I see or hear the word hype). Cultural capitalism, maybe?

I hope I managed to answer your question.

-

December 8, 2021 at 9:03 pm #247315

Here is a ProPublica report about how algorithms can be biased.

So, when we talk about the ritual of capitalization, we need to consider that the operators of an equation, not just the variables, can affect, if not dictate, the outcomes.

Who needs to put a thumb on the scale when the scale is the thumb?

-

-

December 9, 2021 at 3:16 am #247316

Ok… so this seems to have gone down a strange turn. Scot, you seem to be suggesting (and please correct me if I am wrong) that Hype is a Power tactic that is nebulous and largely unmeasurable? if so, I would say that almost everything can be measured, unless we specifically define them in such a way as to make them unmeasurable.

Hype, as defined by CasP, is a ratio that measures the difference between expected earnings, and realized earnings. EE/E

Long term observation of this ratio is the mechanism by which we are able to tell to what degree Analysts are being positive or negative about a valuation.

The Analysts are not the ones with the motives that need inspecting though… Analysts build their valuations and forecasts on various ratios and metrics, but there is always a level of hype that falls outside of the standard equations. If this were not the case, what we would see is an almost perfect match up of analyst predictions for expected earnings and the hindsight of realized future earnings.

This error-gap has only 2 possible explanations. Either the Efficient Market Hypothesis is correct, and information is embedded in the price, which was only known to inside traders who acted on that information, thus distorting price expectations (a position that is fundamentally unfalsifiable), or there is Market Hype at play. And given that we can actively see Market Hype occurring all the time (Elon Musk is a prime example with his tweets regularly affecting share price), my guess is that the Efficient Market Hypothesis is a bunch of hooey, and Hype needs further investigation.

in 2006, Alan Turk from Illinois Wesleyan University, produced a paper in which he formulated some of the most commonly used ratios, introduced industry controls, and then added in a model he developed for Hype.

Unfortunately, his was a once-off study, that looked at a very short-term time-span, during a very specific economic period. As a result, his Hype model did not have the expected outcomes, and only really worked for the Financial and Communication sectors, while showing little to no effect in other sectors. Had there been follow up studies done on all studied sectors, with repeated analysis at every quarter over a number of years, and with a related study of media content verbiage as a Time-series Analysis of all the Market Hype surrounding specific stocks, the data may have revealed the kind of granular Hype I was referring to earlier.

Nonetheless, I still think that given the large discrepancy between forecasts and actual returns, Hype needs further investigation.

-

December 9, 2021 at 3:31 pm #247317

I am going to set aside my musings and other half-baked thoughts for the moment and just focus on the concept of “hype” as it is presented by Bichler and Nitzan in their 2009 book Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder.

To begin:

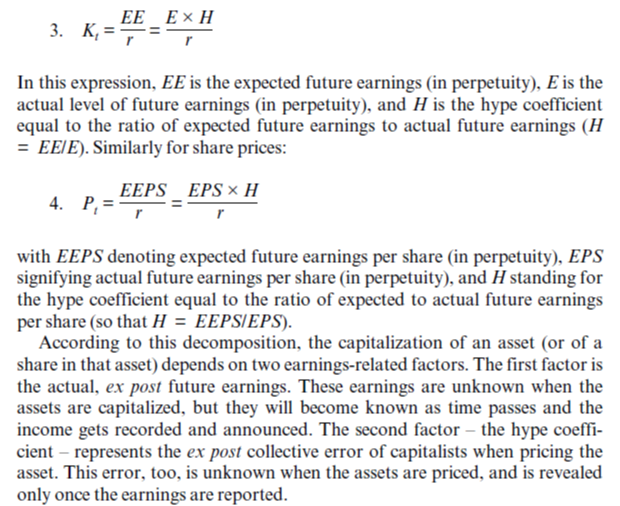

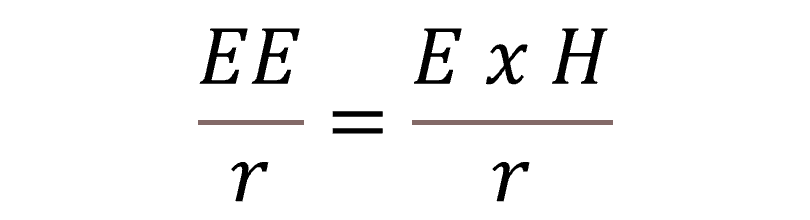

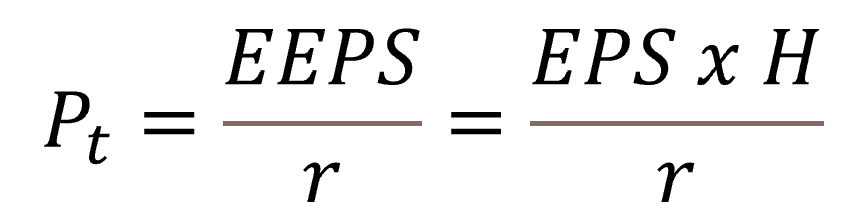

Summarizing

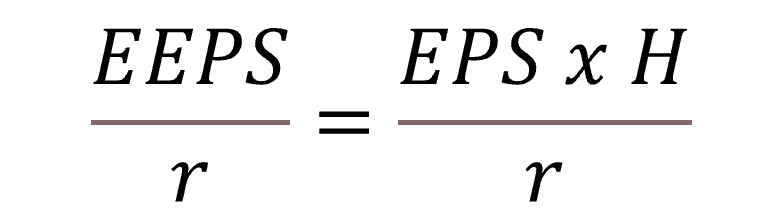

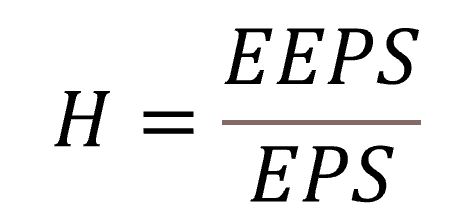

To reiterate, here, EE is the expected level of earnings (in perpetuity), while E is the actual level of earnings (in perpetuity), and EEPS is the expected level of earnings per share (in perpetuity) while EPS is the actual level earnings per share (in perpetuity).

Now, let’s look at the Hype Index of Figure 11.2:

The Hype Index does not measure hype, it measures forecast error. The Hype index cannot measure hype because we do not stand at the end of time, and so we cannot know the final value of EPS.

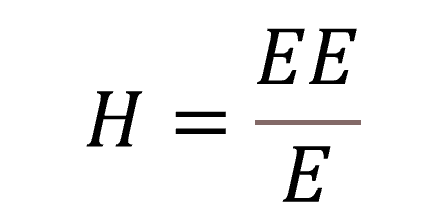

Is the Hype Index useful? Maybe. I can think of one way to test whether what it tells us is meaningful using readily available data. Equation 3 can be alternatively solved for H, as follows:

so

which implies that EEPS should always be equal to rPt, which I am pretty sure won’t prove to be true.

Alternatively, you can recalculate the Hype Index by dividing rPt from a year ago and by the actual EPS for the date in question. Both r (the expected rate of return of the S&P500) and Pt of the prior 12 months are known for or can be calculated for on a daily, weekly, monthly or annual basis. The Hype Index calculated this way should be identical to that shown in Figure 11.2.

I am pretty sure we will find, however, that dividing rPt of twelve months before by the actual EPS of time zero will not yield the same value for H because the value of Pt is based on the weighted average of capitalization of all components of the S&P500, while the EPS of the S&P500 is just a straight summation of all earnings and losses per share without consideration of the relative size of companies or their weighting in the index.

The term “hype” has a lot of baggage. On the one hand, it imputes a particular state of mind to whoever allegedly purveys it. On the other hand, it triggers cognitive biases in those trying to study the underlying phenomenon. The better term for the “Hype Index” is the “Forecast Error Index,” both because forecast error is what is measured and because it neutral and does not foreclose the consideration of potential root causes for the error other than “hype.”

Summarizing,

- Hype as defined by CasP is immeasurable because we can never know the “actual” EPS at the end of time.

- The Hype Index does not measure hype, it measures forecast error on a rolling 12-month basis. The validity of that measurement is unknown but can be tested/confirmed with an alternative method of calculating said error.

- We have no basis for assuming that “hype” is the reason for the forecast error, and we should avoid using labels that impute the state of mind of others, which is unknowable.

-

-

December 9, 2021 at 6:14 pm #247318

Some clarifications.

Definition

In our work, we defined:

(1) hype = expected earnings / actual future earnings

Hype has no moral connotations. You can call it ‘forecasting error’, ‘delusion’, ‘stupidity’, or ‘manipulations’.

In retrospect, hype can be measured for any period — a day, two years (as we have done), a century, infinity. If you can specify expected earnings and measure actual earnings in retrospect, hype is their ratio.

Scot is correct that, strictly speaking, hype is impossible to measure all the way to infinity. We cannot stand at the end of time and look back to see previous earnings. However, under normal circumstances, we can offer a good estimate of till-end-of-time earnings and therefore for till-end-of-time hype. The reason is that the discount factor makes more distant earnings less significant for capitalization, so usually 50 or 100 years, depending on the discount factor, will give you 80-90% or more of the capitalization of earnings all the way to infinity. And 100 years of earnings is certainly something we can examine in retrospect.

You can ignore hype if you wish — but then you’ll be able to say nothing about the gap between actual and expected earnings, and about how this gap is being manipulated and leveraged in capitalism for power ends.

Not a definition

In CasP, we theorize that:

(2) capitalization = future earnings x hype / discount rate

(Note that this is a simple expression, and that under different assumptions regarding the pattern of earning, the formula might differ.)

Scot uses this equation to define hype, such that:

(3) hype = capitalization x discount rate / future earnings

In my view, this is a logical error. Equation (2) isn’t true by definition. It is a theory (in this case, of capitalization), and since a theory can be wrong, it cannot be used to define one of its own determinants (in this case, hype).

S&P500: price and EPS

The price index of the S&P500 is total market capitalization/number of shares.

The EPS of the S&P500 is total earnings /number of shares.

Both are free-float measures, and in that sense they weigh larger firms more heavily than smaller ones.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

December 10, 2021 at 2:15 pm #247324

Some clarifications. Definition In our work, we defined: (1) hype = expected earnings / actual future earnings Hype has no moral connotations. You can call it ‘forecasting error’, ‘delusion’, ‘stupidity’, or ‘manipulations’. In retrospect, hype can be measured for any period — a day, two years (as we have done), a century, infinity. If you can specify expected earnings and measure actual earnings in retrospect, hype is their ratio. Scot is correct that, strictly speaking, hype is impossible to measure all the way to infinity. We cannot stand at the end of time and look back to see previous earnings. However, under normal circumstances, we can offer a good estimate of till-end-of-time earnings and therefore for till-end-of-time hype. The reason is that the discount factor makes more distant earnings less significant for capitalization, so usually 50 or 100 years, depending on the discount factor, will give you 80-90% or more of the capitalization of earnings all the way to infinity. And 100 years of earnings is certainly something we can examine in retrospect. You can ignore hype if you wish — but then you’ll be able to say nothing about the gap between actual and expected earnings, and about how this gap is being manipulated and leveraged in capitalism for power ends.

I have been using your definition of hype. The definitions of E and EE that I rely upon above are cut-and-pasted from p. 189 of Capital as Power.

Your definition of hype implies hype has a value that is fixed at the time of capitalization but unknowable until the future.

Your Hype Index implies hype has a value that is variable. Upon closer inspection, however, each value of hype in the Hype Index actually relates to an independent and discrete act of capitalization (a series of forecasts). Whatever the Hype Index measures, it is not hype as you defined it because each value tests the accuracy of a different act of capitalization over a single year, not the accuracy over the long run of a single act of capitalization.

I have yet to see what insight the Hype Index provides. It seems to exist only to prove that “hype” exists. What has it told us about “how this gap [between actual and expected earnings] is being manipulated and leveraged in capitalism for power ends”? What does it tells about creordering? Fig. 11.2 and its related discussion provides no insight into these questions.

Like you, I suspect that stock prices are often manipulated and leveraged to create winners and losers, but I think this is easier to see when looking at specific companies and sectors of the economy, not the S&P500 generally. To me, the real tell of manipulation is a share price that is much greater than what a properly constructed free cash flow forecast determines to be the “intrinsic value” of the stock. In other words, manipulation is most likely to occur when the capitalization ritual appears to have broken down and cannot explain the actual share price or capitalization of a company. The price is not always right. Current examples of this phenomenon are Tesla and Bed, Bath and Beyond, but they are very different examples, with the former seeming to be the result of the manipulation of dominant capital, while the latter is the result of short sellers resisting dominant capital (the pricing mechanism is a two-edged sword). At one time, Amazon was greatly overvalued, as well, but eventually it lived up to the “hype” and is now fairly priced.

Perhaps I am completely misunderstanding CasP theory. Does CasP assume that the “price is always right,” that share price is always and everywhere determined by the discounting of future earnings, even when there is evidence to the contrary? If so, this would imply that capitalization isn’t really a ritual of capitalists, but an assumption of CasP. Does CasP assume that all capitalists agree that the price is right? If so, why would anyone ever sell? More importantly, why buy a stock that doesn’t issue dividends, which is the case for at least 60% of publicly traded companies, unless you expect the price to increase? Every stock sale has a seller, who is shorting the stock, and a buyer who is going long, i.e., every stock sale involves a disagreement about the future value of the stock.

Not a definition In CasP, we theorize that: (2) capitalization = expected earnings x hype / discount rate (Note that this is a simple expression, and that under different assumptions regarding the pattern of earning, the formula might differ.) Scott uses this equation to define hype, such that: (3) hype = capitalization x discount rate / expected earnings In my view, this is a logical error. Equation (2) isn’t true by definition. It is a theory (in this case, of capitalization), and since a theory can be wrong, it cannot be used it to define one of its components (in this case, hype).

Did they suspend the transitive property of equality without telling me about it?

I used equations (3) and (4), not equation (2), and I used them in the same basic manner that you do, only focusing on different identities.

Now, if equation (3) can be expressed as:

According to the transitive property of equality, it can also be expressed as:

And then you can solve for H:

In the book, you chose a different expression of equation (3):

and then you solved for H

Now, let’s compare what I did with equation (4) to what you did.

If we start with:

According to the transitive property of equality, I can rewrite equation (4) as

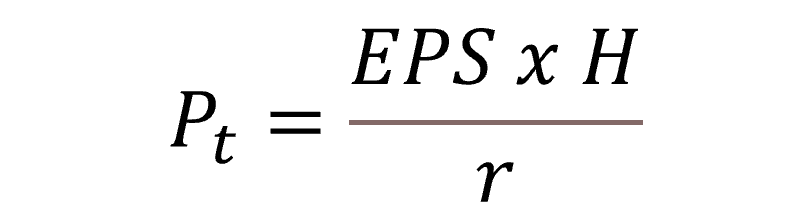

and then solve for H

You chose to rewrite equation (4) as:

and then you solved for H

We simply chose to solve for H using a different sides of equations (1) and (2) (as expressed via equations (3) and (4)). That is, we both used a constituent of a theory to define one of its own determinants.

S&P500: price and EPS The price index of the S&P500 is total market capitalization/number of shares. The EPS of the S&P500 is total earnings divided/number of shares. Both are free-float measures, and in that sense they weigh larger firms more heavily than smaller ones

That wasn’t the case in 2009, when Capital as Power was published. The price was market cap-weighted. EPS was not. When did S&P announce the change? I have not found the announcement, and the SP500 documentation doesn’t really say..

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Scot Griffin.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Scot Griffin.

-

December 10, 2021 at 3:10 pm #247327

I knew a physics professor who, when asked to explain an unclear statement, answered: ‘as I was saying’.

So:

1.

Perhaps I am completely misunderstanding CasP theory. Does CasP assume that the “price is always right,” that share price is always and everywhere determined by the discounting of future earnings, even when there is evidence to the contrary? If so, this would imply that capitalization isn’t really a ritual of capitalists, but an assumption of CasP. Does CasP assume that all capitalists agree that the price is right? If so, why would anyone ever sell? More importantly, why buy a stock that doesn’t issue dividends, which is the case for at least 60% of publicly traded companies, unless you expect the price to increase? Every stock sale has a seller, who is shorting the stock, and a buyer who is going long, i.e., every stock sale involves a disagreement about the future value of the stock.

Yes, the questions you ask here seem to suggest that you might misunderstand our theory. No, CasP doesn’t suggest that the price ‘is always right’ or vice versa, simply because nobody knows what the ‘right price’ is. No, CasP doesn’t claim that share prices are always determined by discounting. There are technical analysts, momentum traders, and other magicians that use alternative rituals, but most if not all believe that, in the long run, prices discount future earnings. No, CasP doesn’t suggests that capitalists agree with one another. And no, CasP doesn’t consider dividends as necessary relevant for stock pricing. As I was saying.

2.

Did they suspend the transitive property of equality without telling me about it?

Transitivity holds when an equation is true. But when an equation is a theory that can be false, you cannot use it to define its own determinants. Concretely in this case, you don’t need to — and cannot — use capitalization to define hype. It is already defined without it. As I was saying.

3.

Our hype debate here is theoretical. The squabble about the S&P500 methodology is practical. Even if the S&P500 isn’t appropriate — and I’m not sure it isn’t — you can devise one that is appropriate. As I was saying.

Perhaps we should agree to disagree.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

December 10, 2021 at 3:48 pm #247329

I knew a physics professor who, when asked to explain an unclear statement, answered: ‘as I was saying’. So: 1.

Perhaps I am completely misunderstanding CasP theory. Does CasP assume that the “price is always right,” that share price is always and everywhere determined by the discounting of future earnings, even when there is evidence to the contrary? If so, this would imply that capitalization isn’t really a ritual of capitalists, but an assumption of CasP. Does CasP assume that all capitalists agree that the price is right? If so, why would anyone ever sell? More importantly, why buy a stock that doesn’t issue dividends, which is the case for at least 60% of publicly traded companies, unless you expect the price to increase? Every stock sale has a seller, who is shorting the stock, and a buyer who is going long, i.e., every stock sale involves a disagreement about the future value of the stock.

Yes, the questions you ask here seem to suggest that you might misunderstand our theory. No, CasP doesn’t suggest that the price ‘is always right’ or vice versa, simply because nobody knows what the ‘right price’ is. No, CasP doesn’t claim that share prices are always determined by discounting. There are technical analysts, momentum traders, and other magicians that use alternative rituals, but most if not all believe that, in the long run, prices discount future earnings. No, CasP doesn’t suggests that capitalists agree with one another. And no, CasP doesn’t consider dividends as necessary relevant for stock pricing. As I was saying.

The questions were rhetorical and intentionally absurd.

As I was saying.

I am not against the concept of hype. It has its place. Unfortunately, what you define as hype and what you claim to measure as hype are two different things, but you discuss them within the same chapter as if they are one and the same.

Disagreement is an acceptable outcome.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Scot Griffin.

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.