- This topic has 30 replies, 8 voices, and was last updated May 4, 2022 at 12:14 pm by Steve Roth.

-

CreatorTopic

-

October 28, 2020 at 10:06 pm #4425

Hello all,

I’m currently doing a post-doc with Kean Birch at York University. He uses the concept of rent, although he’s hardly alone in that. It figures prominently in Piketty and Mazucatto, arguably two of the most famous political economists. Indeed, it may be considered the defining concept of critical political economy.

Conversely, N&B have posted critically about the concept on Twitter: https://twitter.com/BichlerNitzan/status/1315785993023352839

From private conversation, I also know that Professor Nitzan considers the concept unusable because of its dialectical relationship with productivity. Briefly, the returns to rentiership are drawn out of returns to productivity. This usage is definitely at work in Mazzucato and Piketty. One consequence is that it retains a conception of returns that accrue to a productive portion of capital. Obviously this is completely rejected in a CasP analysis.

However, I contend that rent remains a useful concept in part because of the intellectual-theoretical development that ejected it from economics. With marginal productivity theory the neoclassicists eliminated rent and all returns to capital were based on marginal contribution to production. There was no longer any such thing as unproductive ownership. I think we can turn this on its head a la Marx to Hegel: all returns to ownership are rent. Indeed, this can be drawn from Ricardo, who originated the distinction between returns to ownership and returns to production.

This strikes me as analytically and strategically useful. Analytically, none of the current words for the monies that accrue to the owners of capital encapsulate every source, i.e. profits, interest, dividends, share buybacks, acquisitions…. Rent could be the umbrella term. Strategically, it makes sense to use terms that are familiar to people. High profile people are using the term. It has a long political economic history. It has political resonance. So, a redefinition that pushes it in a direction I’d say it is already going is strategically useful.

I actually presented on this subject, identifying rent within the Compustat database, if anyone is interested: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RaFGEJ8zo6w&feature=youtu.be

I will follow up with some other quantitative analysis I’ve done for the purpose of understanding and rehabilitating the concept.

But I’m also open to more discussion for why the concept should be left behind.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

October 29, 2020 at 1:38 am #4427

Troy,

In your video presentation here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RaFGEJ8zo6w&feature=youtu.be, you identify payments to owners and lenders — but not retained earnings or taxes — as rent.

Can you explain why?

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by jmc.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

October 29, 2020 at 1:53 pm #4433

Hi Jonathan,

I figured this would pique your interest!

Rent is considered returns to ownership. I tried to identify every flow from corporate revenue in the Compustat universe going to owners. I identified dividends, interest, share buybacks and acquisitions as monies that flowed to ownership. That does not mean the other flows are going to production. It makes no judgement on the productivity of any particular flow. Instead, it maps where corporate revenues are going.

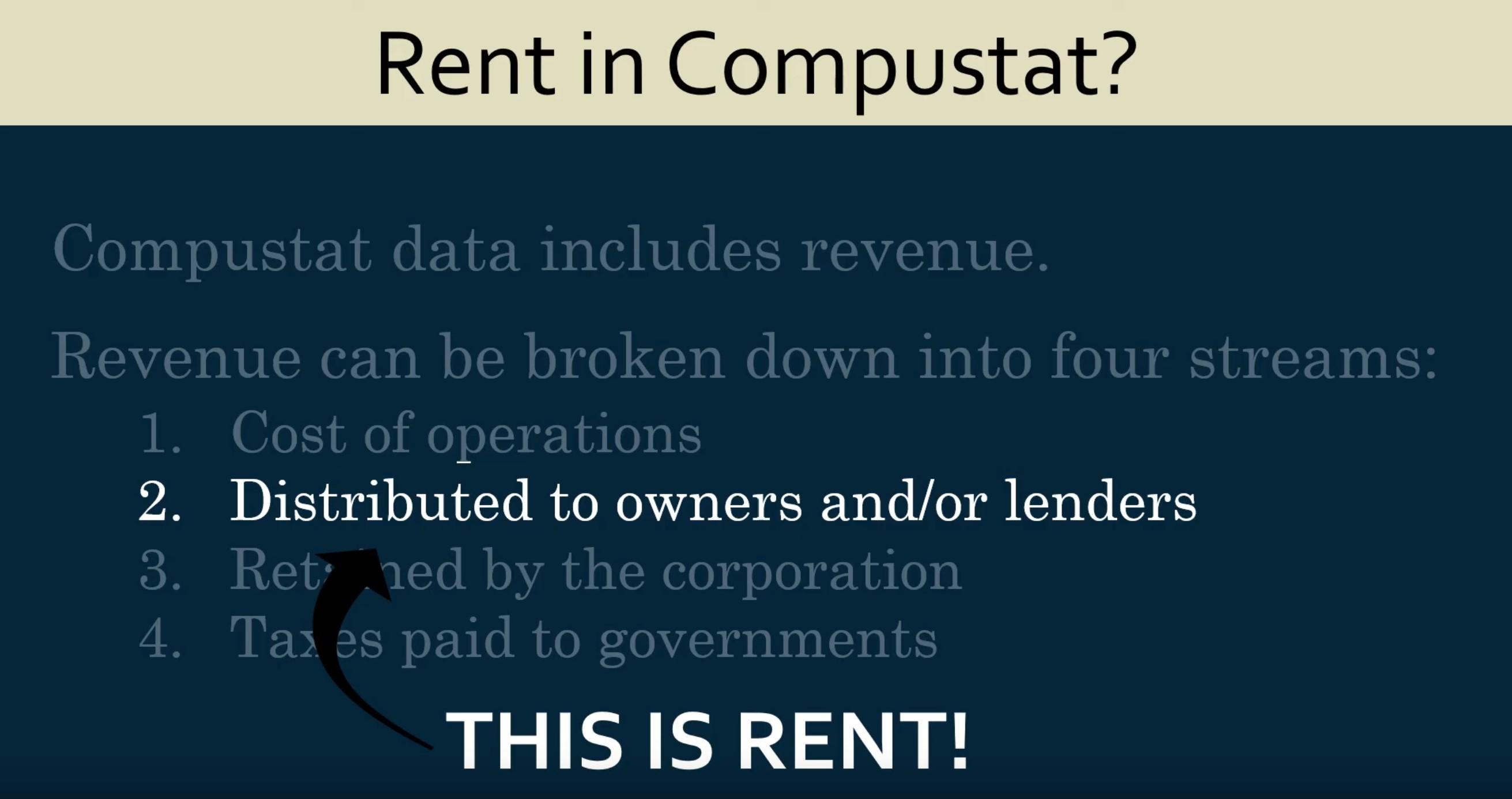

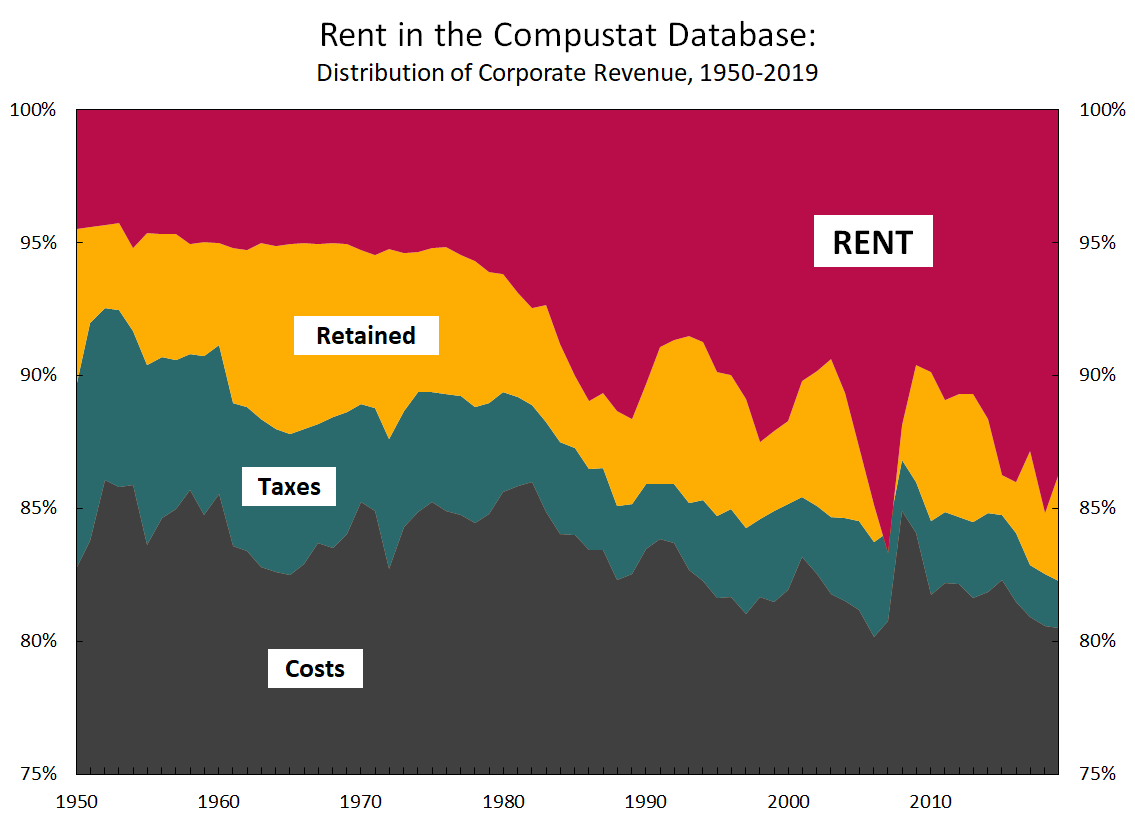

As seen in this image, I created an identity for corporate revenue.

Revenue = Costs + Retained Earnings + Taxes + Rent.

Then, I mapped the distribution to these four channels.

This mapping shows that the share of corporate revenue that flows to owners has been growing, though fitfully, since the early 1980s. The other three categories have been the outlet for a falling share of revenue. It is possible for retained earnings to be negative, as you can see in 2007.

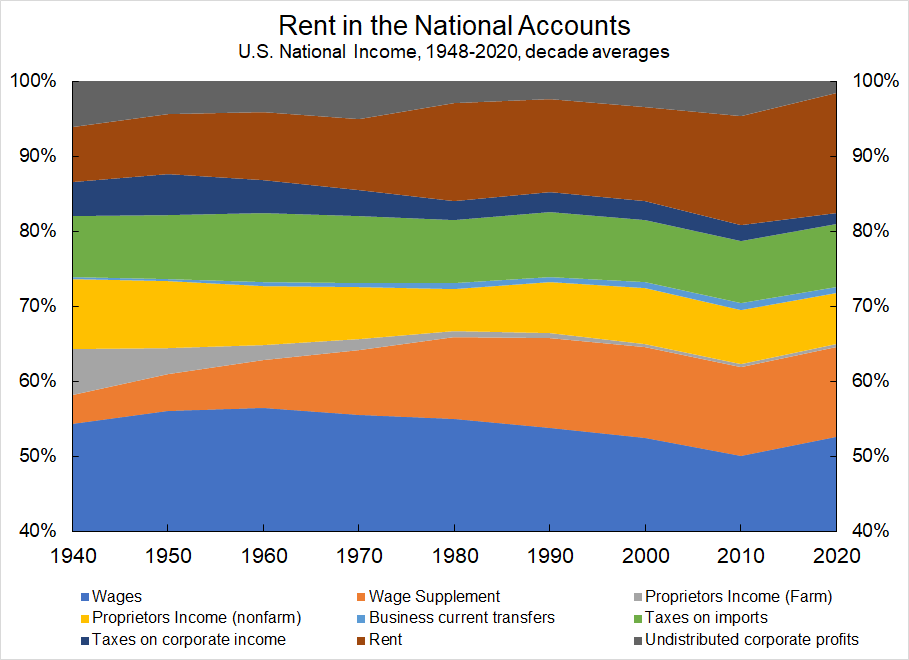

I came at rent through the national accounts as well. The categories are different, and the base is not corporate revenue, but national income. I identified three categories that flow to owners: net interest, net dividends and rental income. (NOTE: net dividends is without capital consumption or inventory valuation adjustment; rental income is without capital consumption adjustment. The end result does not change substantially if those are included or excluded).

This figure shows decade averages for rent plus the other categories that comprise national income.

The story here is similar to that for the Compustat universe: the share of US NI going to owners, i.e. rent, has been growing.

Again, this makes no judgement that the other forms of income are returns to productivity. It just identifies where monies are flowing. And a growing share is flowing to owners.

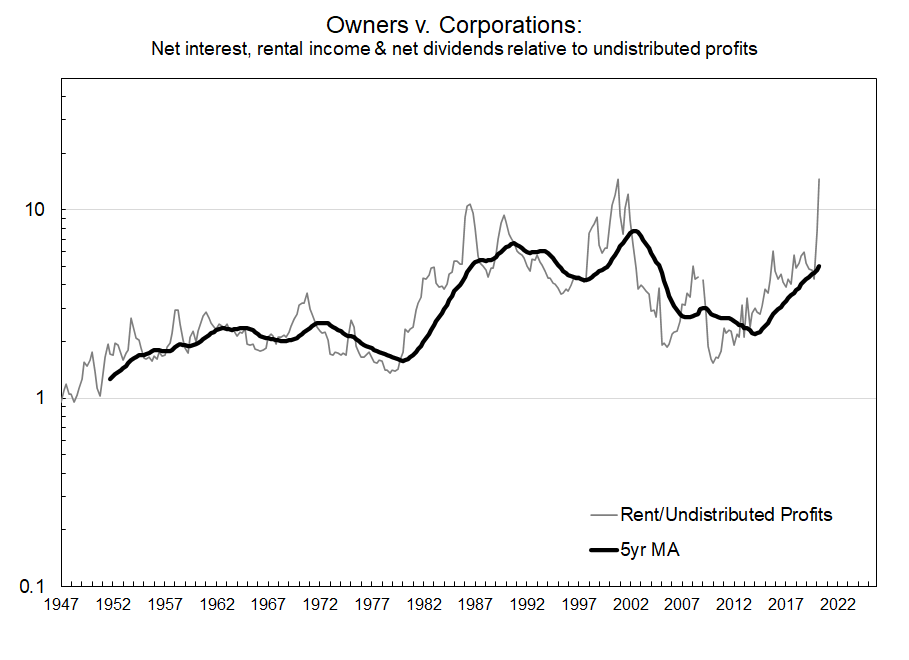

In your Twitter post, Jonathan, you include a figure that showed the ratio between net interest and retained earnings. I questioned why you offered this as a proxy for ‘rent.’ I actually constructed a similar figure, but substituting my measure, which combines net income, net dividends and rental income. I also restricted mine to the post-war era.

This would confirm your challenge of the facile equation between neoliberalism and rent-seeking. The ratio between rent and retained earnings grew with neoliberalism, peaking with the so-called dot-com bubble. It then hit a new low since the 1970s right after the GFC. But it has been rising rapidly since then. And it appears that the pandemic has created an unprecedented redistribution away from corporation and toward owners.

-

October 29, 2020 at 3:38 pm #4435

Troy:

Your basic equation separates revenues into four components.

Revenue = Costs + Retained Earnings + Taxes + Rent.

You use the last component, ‘rent’, to denote ‘return to ownership’ as you call it. You include in this flow dividends, net interest, share buybacks and acquisitions (and maybe rent?).

Some issues with what is included and excluded in your notion of ‘rent’.

1. SHARE BUYBACKS AND ACQUISITIONS. The problem with including this flow in ‘rent’ is that when corporations buy back their shares, their owners receive $X in cash but give up $X in equity. Their net assets do not change. (One often hears that buybacks and M&A lead to capital gains, and that these capital gains are a return to ownership. But these are gains only relative to the historical cost of the assets; when compared to their current market value there is no gain.)

2. RETAINED EARNINGS. In terms of ownership, retain earnings are not different from dividends and net interest. Dividends and net interest flow to the bank accounts (or to spaces under the mattresses) of owners, while retained earnings augment the assets of the corporations they own. As they stand, though, both types of income flow to owners, and only to owners. In this sense, both income streams qualify as ‘rent’ as you define it.

3. CORPORATE TAXATION. This flow is more ambivalent. Since it does not go to private owners, it lies outside your definition of ‘rent’. But insofar as corporate taxes come from the gross income of owners, they can be viewed as part of that income. And if we accept this latter point, then corporate taxes, too, are part of ‘rent’ (just as pretax and after-tax profit are different forms of profit, and pretax and after-tax wages are different forms of labour income).

An there is a broader issue.

4. CONFUSION. Rent has a concrete accounting meaning as well a long theoretical history. Accounting wise, rent is payment for the temporary use of an existing asset such as a house or a car. Theory wise, it often connotes earnings not backed by ‘productivity’. You propose to redefine this term in a totally different way. Your definition might prove useful, but this usefulness is likely to be greatly offset by the confusion it creates.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

November 19, 2020 at 8:44 pm #4517

Hi Jonathan,

The analysis I’m doing is trying to identify where the revenue that flows through a corporation ends up. I’m not focused on what is happening with the recipients. Part of the revenue is used to buyback shares and that money flows to the asset owners, while the company gains back a portion of its outstanding shares. In theory this has a neutral effect on the value of the company and on the value of the assets of the owners, although in practice the exchange will likely cause a market revaluation.

As for retained earnings, I think that it matters who or what is controlling the monies. For some purposes it makes analytical sense to sink corporate assets into the assets of the ownership class — as Zucman & Saez do in their measures of wealth. For other analytical purposes, I think it makes sense to keep them separate. The systematic shift between the monies flowing to owners and the monies remaining with corporations suggests to me that owners view the distinction as relevant. The standard productivist conception would identify retained earnings as useful for investment in productive assets. A business/industry based analysis would draw other conclusions. I haven’t thought explicitly about the owner-corporation distinction from a CasP perspective. But I do think identifying how monies flow through the corporation is a good empirical starting point, and identifying the monies that flow to owners as ‘rent’ is a means to connect the analysis to the history of political economic thought.

-

November 19, 2020 at 10:10 pm #4518

We can agree to disagree for now. And I’m always willing to be re-convinced.

-

November 21, 2020 at 9:53 pm #4528

The systematic shift between the monies flowing to owners and the monies remaining with corporations suggests to me that owners view the distinction as relevant. The standard productivist conception would identify retained earnings as useful for investment in productive assets. A business/industry based analysis would draw other conclusions. I haven’t thought explicitly about the owner-corporation distinction from a CasP perspective. But I do think identifying how monies flow through the corporation is a good empirical starting point

Can we find here a start to a power analysis between owners and executives? Let say our corporation is considered Introvert. The owners, on the other hand, look for economy-wide investment portfolios (so dividends are required) . And on top of that, executives are making money using intenal-industry benchmarks for bonuses which the (much more universal) owners think is misguided.

Does it make sense to look on [dividends/retained earnings] as a proxy for the power of the two groups? -

November 21, 2020 at 10:23 pm #4529

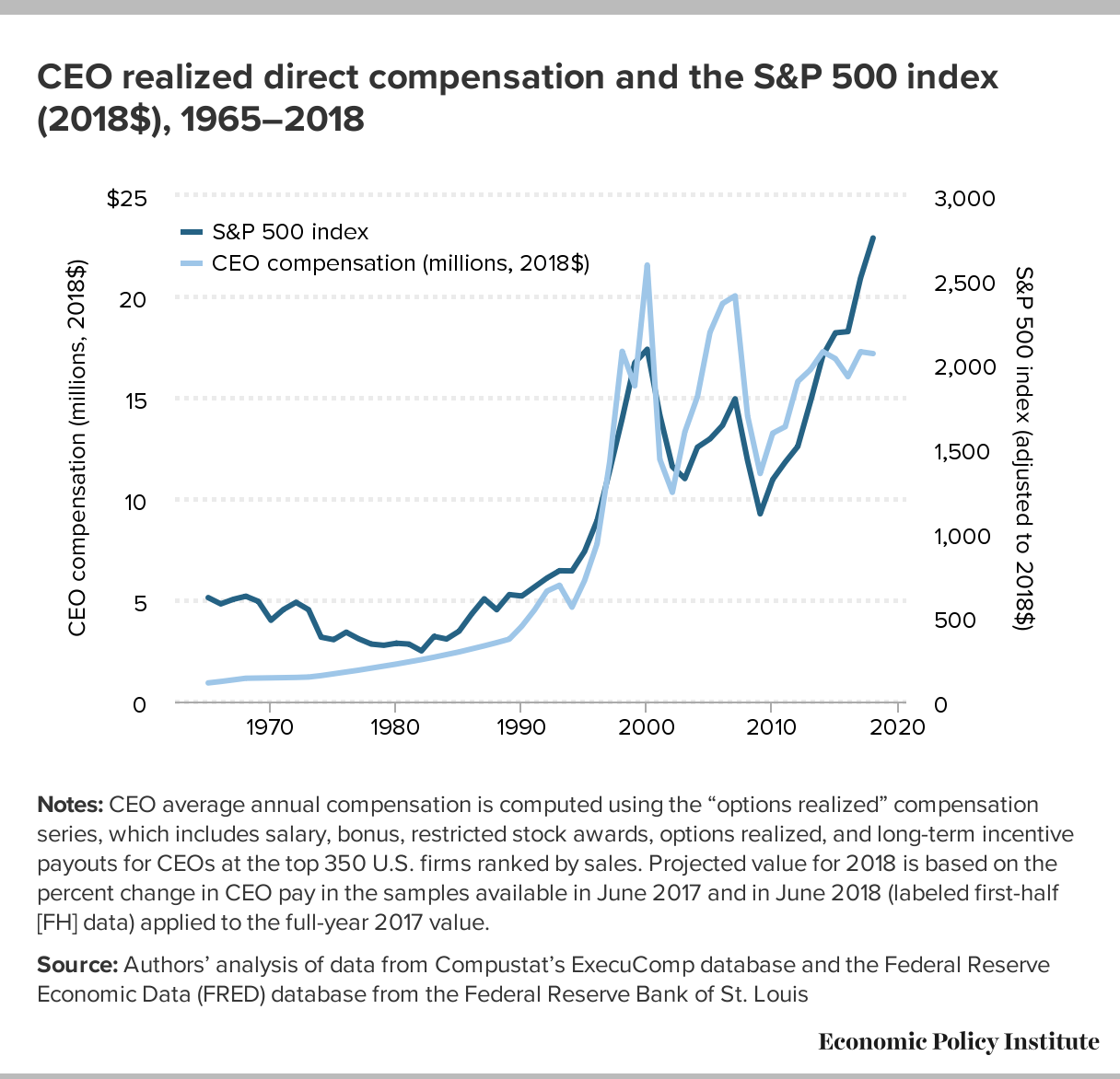

Much of the modern principal-agent debate can be traced to the 1932 work by Berle and Means on the ‘Modern Corporation and Private Property’. But since the 1980s, when top managers became large owners, the debate has cooled off. This chart, taken from a recent paper by the Economic Policy Institute, shows the tight correlation between CEO realized compensation and the stock market. Owners and top managers are no longer at odds.

Also, investors focus on total returns – namely, capital appreciation + dividends. Insofar as the two complement each other, the question of whether owners receive their earnings directly or have the corporation retain them is irrelevant to them. They don’t need the company’s dividends to buy other assets. They can simply sell the company’s stocks.

-

November 22, 2020 at 9:05 am #4532

But since the 1980s, when top managers became large owners, the debate has cooled off

It’s a longshot, but maybe in declining industries (like oil&gas) it’s a resurgent conflict.

Insofar as the two complement each other, the question of whether owners receive their earnings directly or have the corporation retain them is irrelevant to them.

In that case, owners sentiment might be that allowing cash to accumulate in firms’ hands actually interferes with total returns (capital appreciation will be lower since investment decisions would favor own-industry/sector activity, not taking into account all investment alternatives, neglecting proper risk assessments, etc.). I sometimes think to recognize this sentiment in investors’ talk of giving preference to “high-yield dividends companies”.

This goes beyond relative distribution between owners and management. Managers might actually perform “their best” for owners, but they can still be limited to business decisions in a specific industry/sector and need to be “disciplined” with regard to the best benchmark available for re-investment of profits.

-

November 22, 2020 at 9:31 am #4534

The more you disaggregate, the greater the possibility of a discord of the kind you describe.

My point here is merely that the broad transformation of top managers into large owners brought their pecuniary interests in line with those of non-managing owners and greatly lessened the principal-agent problem.

This convergence within the ruling class doesn’t make things better to the vast majority of humanity. Possibly the opposite.

-

November 22, 2020 at 10:52 am #4535

I agree, Yoni. This “business anthropology” doesn’t carry any positive value judgement. At times, the “micro” level seems to offer some concrete points useful for de-legitimization of the existing order in general, and sometimes it’s easier to locate those points outside of the general trend.

-

-

October 29, 2020 at 5:54 pm #4442

There is something to be said for taking a common term and turning it on its head. I don’t personally use the term ‘rent’ much in my research. It seems to be too tied (for my liking) to the concept of ‘unearned income’. That’s a fundamentally unmeasurable concept.

But I do like, Troy, that you’re experimenting with new ways of grouping income. In the end, its the accounting that matters. What you call it is just semantics. (Although, as Jonathan says, many people will ignore the accounting definition and just respond to how they understand your words.)

-

October 29, 2020 at 8:04 pm #4446

D.T: “all returns to ownership are rent”

Right. Couldn’t agree more.

Starting with this definition of economic rent:

Payments to factors of production in excess of what would be required to bring those factors into production

And focusing on household assets and income, the top of the accounting-ownership pyramid, where the “buck” stops:

All measured HH property income is by definition unearned income, received just for owning things. Otherwise it would be classified as earned labor income, received for doing things. (Yes, some proprietors’ “mixed” property income should by “just deserts” be classified as labor compensation; fine. How much?)

Households’ ownership rights, assets, wealth are not factors of or inputs to production. And even if they were, would wealthholders choose to be less wealthy if returns were lower, starving the production line of that valuable ownership “input”? (What’s the elasticity on that?)

Yes, portfolio churn amongst wealthholders, their collective asset reallocation, does affect what enterprises have/get funds to purchase actual inputs.But does a household’s periodic portfolio rebalancing qualify as significant labor “deserving” of compensation for that “input to production?” Seems “in excess” to me; they’d do that rebalancing anyway, wouldn’t they?

And Blair, yes: just call it unearned income instead?

-

October 29, 2020 at 8:13 pm #4445

In your Twitter post, Jonathan, you include a figure that showed the ratio between net interest and retained earnings. I questioned why you offered this as a proxy for ‘rent.’

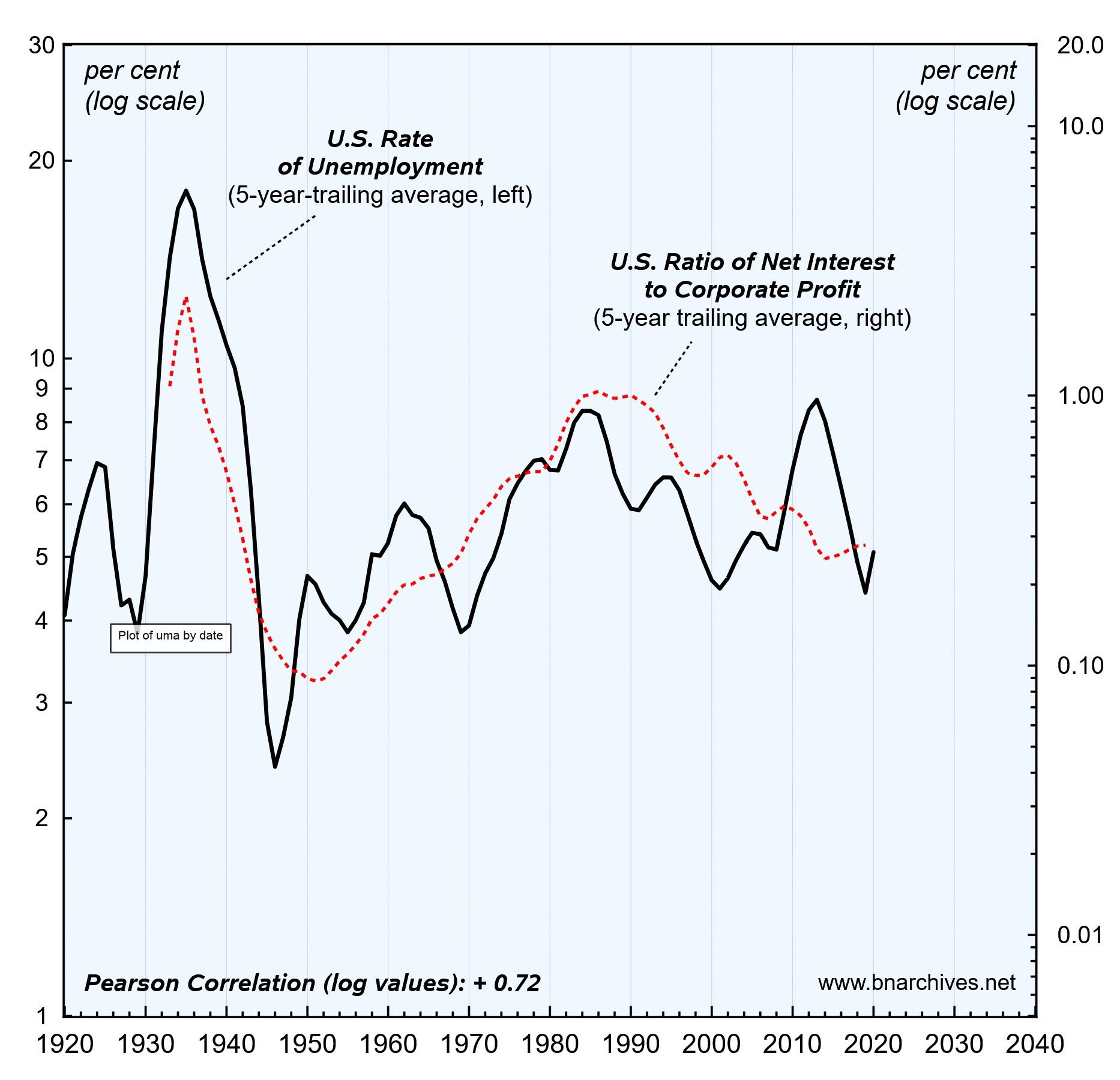

Here is the Twitter chart you refer to, which is an updated version of Figure 12.4 from our 2009 book Capital as Power http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/259/

The chart plots the U.S. ratio of net interest to corporate profit and contrasts it with the rate of unemployment. This ratio and its comparison to unemployment say nothing about ‘rent’ in the specific way that you define it.

We treat net interest and corporate profit as two forms of capitalist income. The main difference between them, we argue, is that interest income is ‘promised’ while profit is merely ‘expected’. We further suggest that net interest, because it is a promise, relies more than profit on strategic sabotage, and propose that when sabotage — proxie here d by unemployment — increases/declines, the ratio of net interest/profit should also increase/decline. This positive correlation seems to continue since we published the book more than a decade ago.

The underpinnings of this relationship are complex, and I admit that we have never actually investigated them in any systematic way.

Tangentially, the graph seems to suggest that, since the 1980s, neoliberalism — which many associate with ‘financializion’ and ‘rent seeking’ — shows a downtrend in unemployment, accompanied by a lower proportion of capitalist income going to interest.

-

October 30, 2020 at 12:29 pm #4448

And Blair, yes: just call it unearned income instead?

Can income, including the income of capitalists, be ‘unearned’?

In everyday English, income is always earned. According to Merriam Webster, to earn means ‘to receive as return for effort and especially for work done or services rendered’. And if you look at any official account of earned income, there is always a description of what the income is earned for — i.e., the ‘effort’, the ‘work’, the ‘service’ being rendered.

So in order to say that a certain income is unearned, we have to demonstrate that that there was no effort/work/service rendered in order to receive it. And since this demonstration depends on our theory, we are back to square one. . . .

-

November 4, 2020 at 7:09 pm #4474

The political usefulness of the concept ‘rent’ also comes into question from the “outside” (analytically speaking):

Wage/salaries for the top 1% income bracket accounts for about 50% of its total income, and for the top 0.01% it accounts for about 20%-30% (depends on the exact type of measurement). Shouldn’t these income type (and possibly others more) be considered ‘rent’ as well, if what we want to denote are capitalistic incomes de-facto? And if so, where does it leave the effectiveness of the concept, now expanded?

- This reply was modified 5 years, 3 months ago by max gr.

-

November 10, 2020 at 12:45 pm #4486

>we have to demonstrate that that there was no effort/work/service rendered

When a person/family/dynasty receives dividends and interest (and capital gains) over decades from holding a portfolio of ETFs — unrelated to any imaginable “compensated” labor — wouldn’t the burden of proof fall rather to proving that they had rendered effort/work/service?

This especially as 60% of U.S. household wealth is inherited — so even the wealth from which that ownership income arises is not conceivably attributable to any effort, work, or service rendered. (Unless, at a rather distant stretch, one presumes that “just deserts” are themselves heritable down multiple generations — a distinctly aristocratic notion.)

Both the title and content of a paper I came across today — “Accounting for Factorless Income” — reinforces my sense that in fact the whole “factors of production” construct is untenable and impracticable. Certainly empirically, and arguably conceptually. And thus the standard factor-based definition of rent I bruited above is as well.

So I’m moving to a firm “no” in answer to this thread’s question.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 2 months ago by Steve Roth.

-

November 21, 2020 at 12:56 pm #4523

The analysis I’m doing is trying to identify where the revenue that flows through a corporation ends up. I’m not focused on what is happening with the recipients. Part of the revenue is used to buyback shares and that money flows to the asset owners, while the company gains back a portion of its outstanding shares.

I’m admittedly a novice on the accounting practices of national accounting. But I am curious why the “Owners v. Corporations” chart has rental income on the owners side, when it can technically include landlords who do not have rental income travel through a corporation. If rental income is counted on the assumption that corporations rent some of their properties to others, this is how the BEA explains the definition:

Rental income of persons is the net income of persons from the rental of property. It consists of the net income from the rental of tenant-occupied housing by persons, the imputed net income from the housing services of owner-occupied housing, and the royalty income of persons from patents, copyrights, and rights to natural resources. It does not include the net income from rental of tenant-occupied housing by corporations (which is included in corporate profits) or by partnerships and sole proprietors (which is included in proprietors’ income). Like other measures of income in the national income and product accounts (NIPAs), rental income of persons measures income from current production and excludes capital gains or losses resulting from changes in the prices of existing assets.

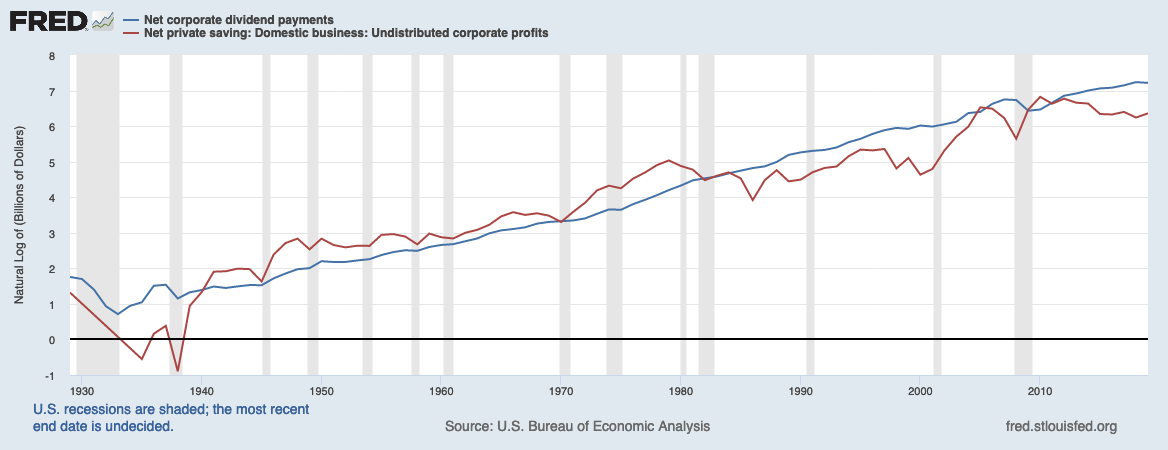

If the intention is to naively look at the flow of profits (before economics defines what is rent or not), your case can be made with undistributed v. dividends. In the United States, at least, the ratio of dividends/undistributed profits has tended to increase since the 1980s.

-

April 27, 2022 at 3:39 pm #247956

Hi All.

Thanks for the engaging discussion, which I’ve just seen one and a half years after Troy’s initial post. And thanks Troy for your beautifully crafted presentation on youtube.

Here are my thoughts:

- There are so many conceptual problems with the category of rent that I’m dubious of Troy’s claim that it is strategically useful to employ. In fact, its problems are so significant that it may lead us to a strategic dead-end. However, it’s worth at least critically engaging with the category of rent given its widespread currency in political economy today.

- One key problem has already been highlighted by Blair and Jonathan: there’s no way of delineating unearned income from earned income. I think this, in an of itself, is a massive shortcoming of the concept: rent qua unearned income is impossible define.

- This problem manifests in different ways in the annals of Marxian and mainstream economic thought.

- In Marxian thought, of course, rent is income derived not from the surplus value generated by productive labour, but rather the ownership or exclusionary control of an asset. One major problem here is that, as Nitzan and Bichler systematically lay out, there’s no way of delineating productive labour from unproductive labour, converting complex labour into abstract labour, and transforming these values into monetary quantities. And given the impossibility of putting the concept of productive labour to work in empirical research, and measuring ‘socially necessary abstract labour’, the obverse concept of unproductive income is equally untenable.

- More fundamentally, as Nitzan and Bichler persuasively argue, all income is based on exclusionary control because in a capitalist context all income is predicated on private property. Developing Veblen’s theory of business sabotage, Nitzan and Bichler put the corporation front and center in the analysis of exclusion. But the same can be said for labour income: the fact that all labourers are in some way in possession of their bodies (as a physiological fact, even if alas in the context of slavery self-ownership is not always sanctified by the law), means that they always have the capacity to withdraw their labour, and the threat of doing so gives them leverage in pushing for a higher wage.

- Arguably Robert Hale’s essay ‘Coercion and Distribution in a Supposedly Non-Coercive State‘ published in 1923 offers the first systematic exposition of the way in which the capital/labour relation is always and everywhere mediated by the threat of withdrawl. It’s worth quoting at some length because Hale underlines how exclusion is at the heart of every transaction, not just those which are most often associated with ‘rents’, and not just those who partake in the pecuniary operations of business:

- “The income of each person in the community depends on the relative strength of his power of coercion, offensive and defensive. In fact it appears that what Mr. Carver calls the ” productivity ” of each factor means no more nor less than this coercive power. It is measured not by what one actually is producing, which could not be determined in the case of joint production, but by the extent to which production would fall off if one left and if the marginal laborer were put in his place-by the extent, that is, to which the execution of his threat of withdrawal would damage the employer…. Income is the price paid for not using one’s coercive weapons. One of these weapons consists of the power to withhold one’s labor. Another is the power to consume all that can be bought with one’s lawful income instead of investing part of it. Another is the power to call on the government to lock up certain pieces of land or productive equipment. Still another is the power to decline to undertake an enterprise which may be attended with risk.

- Hale’s work has been foundational to the sub-field of law and political economy precisely because he shows how the law bears so profoundly on the balance of coercive/disruptive capacities of different parties involved in exchange (whether it be in the form of patents, anti-union laws and everything in between). I think, as exponents of CasP, we’d do well to enfold some of the insights of Hale (and some of his modern-day successors such as Katharina Pistor) into the framework.

- On the side of mainstream economics, rent is equated with ‘super-normal’ profits, and ‘super-normal’ profits are generated when some constraints on competition are imposed by an actor with market power. The problem here is obvious: how do we define ‘normal profits’? In principle, it should be equal to the marginal productivity of capital, but as the Cambridge Controversy showed there’s no way of measuring this.

- Another option would be to use the return on US Treasury Securities as the basis for defining ‘normal’ profits beyond which ‘super-normal’ profits could be gaged. But this simply takes us to the process of capitalization in which future income streams are discounted to their present value, adjusting for risk and using the riskless rate of return as registered by the Fed fund rate. Starting with the universal ritual of capitalization as the basis of our analysis as laid out by Nitzan and Bichler, rather than somehow trying to salvage the conceptually problematic and empirically inoperable category of rent seems to be the best way to proceed.

- Moreover, rather than being a renegade concept that was simply ejected by neoclassical economics as you suggest Troy, perhaps the concept of rent offers the concept of marginal productivity analytical cover: it is the big residual which explains all that which cannot be modelled in the fairyland of perfect competition. By adopting the concept of rent, we may feel we’re moving beyond the categories of neoclassical economics, but we’re inadvertently strengthening its hold over our thinking.

- With all that said, there’s no denying the intuitive appeal of the concept of rent. And here I want to circle back to your comments regarding its strategic usefullness, Troy. Most people – rightly in my view – believe that capitalism is not only inherently limiting, but also extraordinarily generative. Capital is not simply based on the power of negation as Veblen would have us believe, it facilitates and simultaneously circumscribes glorious inventions and mind-blowing innovations. Capitalism creates and it orders (viz. it creorders). But concepts such as rent, market power and super-normal profits do not seem to get us any closer in figuring out out where creation ends in the capitalist creorder, and where limitation begins. And by cleaving to the concept of rent, we may fool ourselves into thinking that we can repurpose capitalism for the better, rather than focussing our attention on constructing modes of organization that operate beyond it.

-

April 28, 2022 at 12:28 pm #247964

Thank you, Joseph, for your very thoughtful response to my initial post. It feels like I posted that a million years ago. It is hard to believe it was only a year and a half.

A proper reply will require more time. But I wanted to acknowledge the post. I hope it represents a fruitful rejuvenation of dialogue. I will offer a quick rejoinder [NB: I’ve come back to acknowledge that it is becoming more than a ‘quick’ rejoinder].

More and more, I’m compelled to argue for a political economy. And my contention is that this is an inescapably moral matter: who gets what? Why?

One of the grand defences of capitalism is connected to the issue you raise at the very end: the relationship among capital, capitalization, and creation. Disruption. Creative destruction. Entrepreneurship. Innovation. All of these get pointed to as the basis of accumulation and the justification for capitalism. And it works because, as you note, there is an undeniably creative component. However, the equilibrium economists want us to accept that markets will properly filter this creative output by responding to consumer desires. On the one hand, as N&B have persuasively argued, this obfuscates the role of power. On the other hand, this tries to eliminate any moral concern. It is not, we are told, our place to judge the autonomous consumption decisions of sovereign individuals. That means there can be no moral judgement of the creativity that gets encouraged, supported, and proliferated by profit-seekers.

I suspect those who hold and defend this position includes both those convinced that we can, and should, have an economy free from moral consideration—except as a matter of personal consumption choice—and those who know the argument merely diverts attention from the morals at work.

Those of us who hope for a more just economy should grab onto the need for moral consideration with both hands. This basically takes us back to pre-Smithian/Physiocrat political economy, which was heavily focused on “just price”.

I suspect we all agree that there is not, and cannot be, a determined or mechanical relationship between productivity and income, especially when we try to aggregate across outputs, or reduce to a single input. So there is no means to distinguish between productive and unproductive income, earned and unearned income. But as you note, many people want some sort of reward for socially beneficial invention, including for greater efficiency. The classical economists thought that is what profit was. And they thought it was just, but also economically determined. Rent, however, was seen as a reward to control, and largely rooted in archaic, unjust institutions.

From our vantage point, where there is popular support for rewards to beneficial entrepreneurial endeavour, and widespread recognition that much of the current income and wealth distribution is unjust, rent offers a useful term. Can we identify the earned, productive income? No. Can we identify the returns to ownership? To a large degree, yes. If anything, it strikes me that profit is the less useful term for our purposes, since it has always been connected to the productivity of capital.

We cannot look to systems of production to tell us how much of the social product entrepreneurs ought to claim. So, let’s have the difficult discussion to decide. From a moral perspective, what should the reward for socially beneficial creativity be? It is earned not because the economy dictated but because the community decided. And the rest that is captured by anyone in excess of their contribution, by virtue of their control, is rent.

-

April 29, 2022 at 7:58 am #247971

Hi Troy,

Thanks for your reply. The following formulation you offer is very elegant:

“We cannot look to systems of production to tell us how much of the social product entrepreneurs ought to claim. So, let’s have the difficult discussion to decide. From a moral perspective, what should the reward for socially beneficial creativity be? It is earned not because the economy dictated but because the community decided. And the rest that is captured by anyone in excess of their contribution, by virtue of their control, is rent.”

However, what you propose here is actually what we already have! True, the ‘community’ that you envisage is no doubt much more egalitarian and democratic than the kinds of communities that presently play a decisive role in determining what is and what isn’t a legitimate income. Nonetheless, from patent law, to regulations on interstate commerce, to laws on minimum wages, to the prohibition on slavery, to provisions on health and safety, to restrictions on speculation, to anti-trust law, the moral questions about who should get what is already central to how the distribution of income and power is governed across societies. While these moral questions are often dressed up in legalese, adorned in the dry language of consumer welfare and individual rights, and obfuscated by technocratic nomenklature, this doesn’t make the issues that they tackle any less moral. In fact, it couldn’t be any other way: precisely because there is no objective means of determining marginal productivity, societies develop intersubjective means of determining the legitimate distribution of power and income.

The key question, therefore, isn’t whether a decision should be made on “how much social products entrepreneurs ought to claim”. This “difficult decision” as you call it, is being made everyday, not by ‘the market’ as such, nor by some democratic assembly as we might wish, but rather by highly complex networks of heterogeneous actors including lobbyists, lawyers, government officials, labour unions, NGOs and much besides. The key question is whether the community that decides now, is the kind of community that we want to be making the decisions. And here Hale’s 1923 essay is once again instructive and therefore worth quoting at length:

“The channels into which industry shall flow, then, as well as the apportionment of the community’s wealth, depend upon coercive arrangements. These arrangements are put in force by various groups, some of whom derive their coercive power from control over governmental machinery, some from their own physical power to abstain from working. The arrangements are susceptible of great alteration by governmental bodies, and governments are concerning themselves more and more with them. Important interests are affected by the shape that these arrangements shall take. It is difficult to measure the interests, and even if they could be measured, there are no simple rules for determining how conflicts between them should be settled. The ” principles of justice ” supposed to govern courts do not suffice. Whatever accepted ” principles ” there may be, scarcely envisage the problems. Should they be settled on the basis of an enumeration of the persons affected? Representative government with a democratic suffrage is a crude (a very crude) device for bringing about settlements on this basis. Yet it may be doubted if the basis is a satisfactory one. Moreover the interests of vast numbers of persons outside the area where any one government holds sway may be affected by its decisions; and these interests at present obtain no representation in its councils. If the area is one rich in natural resources, it makes a great difference to many who live elsewhere how the concessions are apportioned, whether the resources are exploited at all or are locked up, how they shall be rationed (in case the supply, at the price charged, falls short of the demand), and what government shall control the disposition of any revenues derived from their taxation. Since the foreign interests have no representation in the local government, we find them bringing pxessure to bear on it through the foreign offices of their respective home governments. We find attempts to formulate ” principles ” concerning concessions (such as the ” open door”), and we find a desire for annexation. We find the foreign governments disputing with one another over these matters, which contain the most fertile seeds of modern warfare.”

One major insight from this passage, which is also clear in the work of Nitzan and Bichler, is that the moral question of who gets what is ultimately determined by the distribution of power. This poses a severe challenge for egalitarians, since returns to power are recursive and self-reinforcing. The more wealth and income accrues to the powerful, the more power they have to further augment their gains. And unfortunately this dynamic of escalating inequality only appears to be halted by mass warfare and other life-shattering disruptions. But putting this issue aside, as Hale astutely point out, even if we were to develop a more egalitarian and democratic community to arbitrate on matters of distribution, delimiting its exact boundaries, controlling its internal dynamics, and determining the principles of justice that govern it, would be fraught with complexity. In the face of these challenges, all we can do – following Nitzan and Bichler – is make explicit how the qualitative workings of power and authority shape quantitative patterns of income and wealth. Mobilizing the concept of rent may help us push back against the increasing returns to power, but it also threatens to reinforce the view that there exists a domain in which income can be generated independent of control and restriction.

-

April 29, 2022 at 3:36 pm #247976

One major insight from this passage, which is also clear in the work of Nitzan and Bichler, is that the moral question of who gets what is ultimately determined by the distribution of power. This poses a severe challenge for egalitarians, since returns to power are recursive and self-reinforcing. The more wealth and income accrues to the powerful, the more power they have to further augment their gains. And unfortunately this dynamic of escalating inequality only appears to be halted by mass warfare and other life-shattering disruptions. But putting this issue aside, as Hale astutely point out, even if we were to develop a more egalitarian and democratic community to arbitrate on matters of distribution, delimiting its exact boundaries, controlling its internal dynamics, and determining the principles of justice that govern it, would be fraught with complexity. In the face of these challenges, all we can do – following Nitzan and Bichler – is make explicit how the qualitative workings of power and authority shape quantitative patterns of income and wealth. Mobilizing the concept of rent may help us push back against the increasing returns to power, but it also threatens to reinforce the view that there exists a domain in which income can be generated independent of control and restriction.

I think you are misreading Hale, particularly if you consider the broader context of his work in legal realism. He had no confusion regarding who gets to determine the distribution of power: it is the state. See, e.g., “Rate Making and the Revision of the Property Concept” (1922) 22 Columbia Law Review 209.

The purpose of much of Hale’s work, including “Coercion and Distribution in a Supposedly Non-Coercive State,” was to undermine the arguments of laissez-faire proponents against state interference in markets. Even before “Coercion and Distribution,” Hale recognized that the state not only interfered in the market but defined it and, thus, laissez-faire was self-serving nonsense.

“Coercion and Distribution” was Hale’s response to a laissez-faire proponent, Thomas Nixon Carver, a kind of review of Carver’s recent treatise on economics. The passage you quote above concludes with the following two sentences:

All such problems of democracy, representative government, international economic conflicts and their adjustments, fall properly within the scope of a treatise on The Principles of National Economy. They are not discussed by Mr. Carver.

In context, Hale was not shrugging his shoulders and suggesting we we walk away from the complexity he just cut through like a laser. He was arguing that Carver should have addressed that complexity in The Principles of National Economy, and his failure to do so rendered the treatise useless.

Hale also ended his 1922 “Rate Making” by questioning the ability of judges, administrative commissions and legislatures to comprehend and address the complexity of the issues, but he also made clear that such complexity was no excuse for refusing to address the reality of the issues they were required to decide:

Whether the ultimate determination of this important policy question ought to rest in the hands of small bodies of men not chosen primarily because of their views of policy, is another question. It raises the whole problem of representative government and involves international complications at times. It might be better for some official or un- official body to draft a detailed report on the revision of the entire institution of property. Meantime the fact remains that the immediate, if not the ultimate, determination of this policy is in the hands of courts and commissions. Nothing is to be gained by their failing to make a candid re-examination of the functions of ownership. The man at the steering wheel, regardless of his personal qualifications, has to use his own best judgment where to steer, pending definite instructions from the “boss.”

-

April 30, 2022 at 11:18 am #247980

I’d just like to revisit, (disagree with,) and revise two statements that arise here, which I think are importantly incorrect:

Blair (10/29/2020): “the concept of ‘unearned income’. That’s a fundamentally unmeasurable concept.”

Troy (4/28/22): “there is no means to distinguish between productive and unproductive income, earned and unearned income.”

Revision: “there is no means to distinguish *perfectly* between…”

It’s quite straightforward to extract these earned/unearned measures from the national accounts’ household tables. (It’s much more difficult, and may well be impossible, through the lens of the corporate sector. The attempt itself arguably participates in the “valorization,” lionization, even deification of “producers” cum “entrepreneurs” cum “capitalists.”)

Start with a basic statement that’s quite straightforward both for broad rhetorical purposes, and as a precise, technical, economic (and accounting) term of art: Earned income is received by households, people, in compensation or reward for doing things: providing inputs to production. The remainder, all other tallied household income, is unearned.

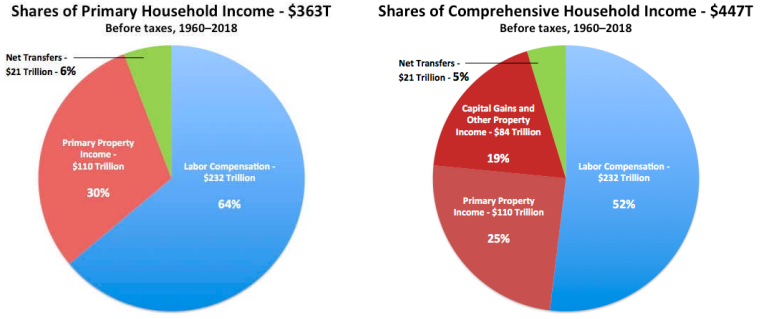

Then divide unearned income into two categories: income received for owning things, and income received as social transfers. These categories are all straightforwardly visible and summable in national accounts of the household sector. Here’s a look at that. It’s just a rearrangement and relabeling of the Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts’ household Table S.3.

(The righthand pie shows comprehensive, balance-sheet-complete Haig-Simons income, which includes $10s of $Ts in holding gains accumulated by owners purely for owning/”holding” stuff.)

There are accounting judgment calls and measurement issues lurking behind this (I’d be delighted to share what I know of those), so it’s not some perfect picture handed down from Mt. Horeb. For 20 years, eg, Jeff Bezos claimed $88K a year as earned income on his tax returns. But (I’ve run the numbers) giving “credit” to “entrepreneurs” for the untallied value of their labor “contributions,” inputs to production, even at its most extreme estimation, would only shift the earned/unearned percentages above by a few percentage points. There are many other etcs, but the proportions you see here are quite solid.

IMO, “unearned” carries all the rhetorical and moral baggage we need, in a usage that most/all can grasp at a glance. And the fairly simple deconstruction above is at least a very close approximation of what’s needed for theorists, empirical researchers, and modelers: a technical term of art that’s precisely defined by a whole web of mutually coherent accounting identities.

So IMO “rent” is just unnecessary for either purpose, and even contributes to the fog of obfuscation and diversionary chaff that is a dominant tool employed by the ownership class to accumulate and maintain its wealth, power, and privilege.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Steve Roth.

-

April 30, 2022 at 3:22 pm #247982

There are accounting judgment calls and measurement issues lurking behind this (I’d be delighted to share what I know of those), so it’s not some perfect picture handed down from Mt. Horeb.

Please share, Steve! Also, I know that Troy often remarks on the importance of studying accounting if you want to understand capitalism. Curious that it’s rarely taught in economics. It would be great to have an accessible resource that outlines all the different ways of defining/measuring income.

About ‘unearned’ versus ‘earned’ income. If the goal is to spark a political movement, then I think that language is appropriate. Certainly many people on the left will agree that capital gains on property are ‘unearned’. Hell, even mainstream economists think capital gains are ‘unproductive’, which is why they keep it out of the national accounts.

However, for the scientific study of capitalism, I’m hesitant to use that language, largely because it is so easy to criticize.

-

May 1, 2022 at 10:44 am #247984

>Please share, Steve!

I realize that that blanket offer may have been overambitious. Quite a lot to unpack. I will say that understanding sectors as economic units is key. Also the relationships between sectors, households in particular. They are the top of the accounting-ownership pyramid; all firms’ equity-ownership shares, at market prices, are included as assets on the household-sector balance sheet. (Putting aside the rest of world (ROW) sector for the moment.) The HH sector is also where the primary import of accounting stocks and flow “comes home” in human lived experience across lifetimes, families, and dynasties.

I have some issues with some constructions and implicit presumptions of national accounting presentations, but full credit where due: they’ve been thinking really hard about what their measures mean, and how to best present them, since Kuznets and co. in the ’30s. Most significantly this century in the 2003, UN-sponsored System of National Accounts. There’s “a vast literature” on how we can think about and understand this stuff in numeric, monetary terms.

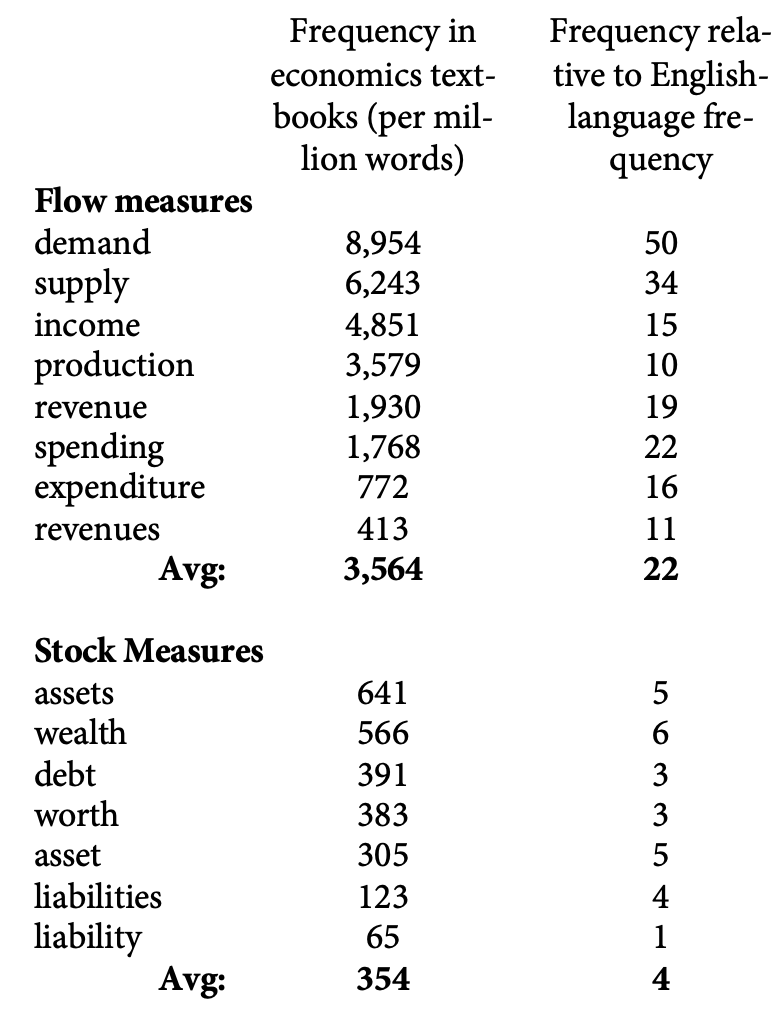

Meanwhile, yes what Troy said. Accounting (and business) classes don’t even count as electives for econ majors at Harvard, MIT, or U Chicago. etc. And as for the “balance-sheet-complete” national accounting that I constantly bang my spoon on the high-chair about, here are some word counts of accounting terms from econ textbooks—with full credit to you (!!) for giving me the ability to do these counts.

(Note that >50% of the flow terms shown here are the dimensionless abstractions supply and demand—not actually measures but imagined curves.)

I’ve pondered for a while putting together a teaching unit on accounting for econ classes. Thinking the key understandings could be imparted in maybe two weeks (?), ten hours of class time.

Okay stopping there. A more narrow and fulfillable offer: I’d be happy to answer more specific questions about national accounting that I may have answers to.

In the meantime, I’m just polishing up the following, which gives detailed derivations of “personal income,” and its relationship to personal-sector balance-sheet assets. I hope in very clear terms. Short-form takeaway: “saving,” as constructed, completely fails to explain asset/wealth accumulation.

Thanks,

Steve

-

May 1, 2022 at 12:43 pm #247985

Many thanks Steve for the interesting posts, though I must say they leave me puzzled.

You write:

Earned income is received by households, people, in compensation or reward for doing things: providing inputs to production. The remainder, all other tallied household income, is unearned.

.

What do you mean by ‘doing things’ and ‘providing inputs to production’? For example, don’t owners of land — the most notorious ‘rentiers’ — provide inputs to production, as do owners of ‘capital goods’? According to your definition, their incomes are as ‘earned’ as those of workers.

In our work, we argued that the problem with the ‘earned/unearned’ distinction hasn’t changed since the physiocrats. Despite endless claims to the contrary, nobody knows the ‘true production function’ because no such function exists. Production is a hologramic societal process. Its ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’ cannot be objectively identified, they have no universal units, and their complex cross-section and temporal intricacies cannot be disentangled.

Unless we decipher ‘who’ produces and ‘what’ they produce, how are we to conclude who earns and who doesn’t?

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

May 1, 2022 at 3:05 pm #247987

>don’t owners of land — the most notorious ‘rentiers’ — provide inputs to production, as do owners of ‘capital goods’?

Putting aside eg landlords’ and other owners/entrepreneurs actual management and other work on directly owned properties/firms, which is properly seen as earned income (but which is often not reported as such to the IRS by owners/landlords because our tax laws are stupid; cf Bezos’s $88K a year in reported earned income):

Owners only provide “inputs” in the wildly stylized sense used in many econ models and silently in ubiquitous mental models. An Amazon shareholder is literally treated as if they own warehouses directly, and they’re selling capital services provided by the warehouses to the corporate entity. (Capital services are reasonably conceived as inputs to production, IMO.)

Shareholders “own” the warehouses, and they’re sacrificing their own use of the warehouses so Amazon can use them, so they’ve justified or “earned” that income without actually doing anything. Hope you’ll understand why that seems like a pretty crazy, far-fetched abstraction to me.

(Irresistible aside: if we take humans’ inalienable, self-owned “human capital” seriously—the long-lived productive stocks of goods that we call health, abilities, skills, knowledge, etc, produced through investment spending on health, education, home caregiving, many et ceteras)—then workers are also selling their capital services as inputs to production, when they work for wages. This, I should add, is the overwhelmingly dominant capital-services input to production, measured in $ magnitude…)

But really c’mon: household shareholders, bondholders, REIT owners, do nothing but…own financial instruments (including titles to real estate). That’s what they’re compensated for: just owning stuff. There’s ~zero human effort involved. (Their arms-length hired management does all the work, presumably and properly reporting their income as earned; owners get the remainder/profit.)

Ownership, in and of itself, is not an input to production.

In the “real,” empirical, and extremely measurable world of monetary values (income, assets, etc.), we can draw a quite bright line between most earned and unearned income. Even if there’s also a large (15%?) gray area. And we could shrink that gray area. Suppose earned income were taxed at a lower rate than unearned. Asset owners would jump all over themselves to report their (justifiable) hours actually worked, to qualify income as earned for tax purposes. (Maybe they’d even do more work; incentives matter, right?) Just one example.

At its most extreme and strained, you hear meritocratic justifications about wealthholders’ annual hour or so spent rebalancing their portfolio, as doing the noble, necessary social work of “asset allocation.” As a very moderately wealthy person living almost wholly off of (unearned) returns to my wealth, I just can’t even.

Hoping this helps clarify the frame in which I’m thinking, trying to understand all this stuff…

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Steve Roth.

-

May 1, 2022 at 3:42 pm #247989

Yes, ownership per se does not affect production — a statement we both seem to accept — but it also means that provision of inputs as such cannot be a yardstick for earned income.

So we are left with earned income = income of those who participate directly in production.

But what does it mean to ‘participate directly in production’? If Bezos goes to work one day a month, should we count him as participating and his income as earned? If I’m digging holes and filling them up, do I participate in production? If someone manages a chemical weapon company, sells advertisement, produces cigarettes, or runs a bank, is their participation productive?

It seems to me that production is an incoherent basis for classifying income in capitalism. It is also too narrow a focus for organizing a democratic alternative.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

May 3, 2022 at 10:29 am #247994

>earned income = income of those who participate directly in production.

“Of those” implies a defined class or category of economic actors. I’d define it differently, just categorizing (household/personal) income.

Income received in recompense for human effort.

This is the kind of categorization and labeling that accountants do constantly, in innumerable realms and situations. In practice the huge bulk of personal/HH income (even including what I call comprehensive [Haig-Simons] income) is straightforwardly measured and categorized by that criterion.

There’s 1. earned labor compensation, and 2. all the rest (unearned), which we can categorize as A. (net) gov transfer income, or B. property income received in recompense for owning stuff. Most of this is easily assembled from the national accounts.

There are remaining judgment calls, for sure, comprising maybe 15% (?) of HH income. But again, even with fairly extreme accounting choices there, the labor/transfer/ownership split only shifts by a few percentage points.

We can certainly interrogate the concepts, methods, and measures used in the national accounts. But I don’t think we can reasonably say that earned/unearned income are unmeasurable.

-

May 3, 2022 at 3:53 pm #248025

Income received in recompense for human effort.

In my view, shifting from ‘productive contribution’ to mere ‘effort’ still leaves us with no solid basis to justify/critique income.

1. Pure (absentee) owners may argue that, while they exert no current effort here and now, their income compensates for past effort — theirs or their predecessors’.

2. For those who do exert effort, we don’t know whether their effort affects production positively or negatively, and by how much.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

May 4, 2022 at 12:14 pm #248036

I also struggle with the issue of “justifying” income, and 100% agree with your #2 — that attempts to quantify work-hours’ contribution to production of stuff is fruitless. Because, there is not even a conceivable common unit of measure for heterogenous “output.” What’s actually measured, what can be measured, is spending/purchases (and their obverse, income). It’s silently assumed that that $ measure equals the “value” of production/output, labeled “GDP” and ubiquitously conceived as “real” even though it’s imputed from measured spending goshdarnit.

That questionable practice doesn’t disqualify the actual spending and income measures, however. They’re very “real.”

The fact is that in 2020 in the U.S., 142M people worked 244B hours, and received $11.6T in compensation for that work. (All “estimates” of course, like all accounting measures; some are more solidly-grounded estimates, some less.) In very real practice, those hours, efforts “justified” that income. (And we have the means to categorize/analyze that income in many ways — by income or wealth percentiles, age, race, etc. etc.)

Meanwhile in total people received $16.6T in income (plus $11T in accrued holding gains not counted as “income”). That’s $5T–$16T in income that is explicitly not “justified” by hours worked/human effort, at least in this tabulation. Tax treatments and diverse other institutional practices certainly make this earned/unearned distinction, with real import for people. It not just theory; it’s ubiquitously practiced.

To raise a topic that has better “legs,” IMO, than the two issues/examples you’ve raised. This is usually discussed in terms of “proprietors’ labor compensation,” as part of their “mixed income.” Shouldn’t some portion of their apparently non-labor ownership income be categorized and “justified” as labor income, even though they don’t report it as such (for perverse tax reasons)? My personal answer would be yes, sure — for important analytical reasons even though it slightly undercuts my preferred progressive rhetorical stance.

Income accountants/economists have been interrogating the issue for more than a century. There’s a good 2017 BEA discussion here. Piketty & co.’s approach to the issue is well explained here. It’s been addressed innumerable times in issues of the Review of Income and Wealth going back to ’51 and the work of Kuznets & co.

But yet again: even the most extreme attribution of proprietors’ mixed income to labor only shifts the labor/ownership shares by a few percentage points. It’s an edge case, pretty small magnitude, and IMO doesn’t justify saying that earned/unearned income is “unmeasurable.”

As for the far broader claim in #1 that owners “may offer” — that ownership income is “justified” as recompense for past labor (plus let’s not forget their “patience” and deeply virtuous abstinence in hoarding their wealth… #GotMarshmallowTest?) To keep this brief I’ll just say it’s purely specious and self-serving, like so many justifications trotted out by the ownership class going back to time immemorial. That they might (do) make that specious argument provides no reason, IMO, to accept that argument as disproof of a thoroughly well-considered distinction between earned and unearned income, measured/estimated with quite excruciating care.

Thanks for listening…

Steve

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Steve Roth.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Steve Roth.

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.