Home › Forum › Political Economy › Is the economics/politics duality Capitalism’s Noble Lie?

- This topic has 12 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated May 25, 2021 at 1:06 pm by Scot Griffin.

-

CreatorTopic

-

May 19, 2021 at 4:16 pm #245673

CasP rejects the economics v. politics duality as false, which it is on its face, but has it been made true because so many believe it to be?

I would argue yes. As a practical matter, the belief in this foundational lie of Capitalism has led governments to cede a significant portion of their sovereign power to Dominant Capital, which is, always and everywhere, Finance. While this power domain began with the delegation of control over the money supply to Finance (which is the foundation of the depth domain of strategic sabotage), Finance has expanded its domain to create and control capital assets and capital markets, which are the foundation of the breadth domain of strategic sabotage.

If one accepts that Dominant Capital is sovereign of its own power domain and that it wields its power within its domain to execute strategic sabotage of the broader economy, then (1) the real v. nominal duality is true, but the cause and effect are reversed, i.e., the nominal drives the real and does not merely reflect it, and (2) manifestly, the economy is not self-equilibrating.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

May 21, 2021 at 2:02 pm #245677

None of this makes those dualities true.

Dominant capital remains thoroughly political. My quippy definition of politics is “the art of living life in common.” Markets are supposed to do away with politics because the utopian market ideal is that exchange among individuals renders unnecessary negotiation among groups. Of course, they never do so. Braudel notes that in 14th century Italian markets, there was a saying that one should remember we make friends, as well as money, in the market. They understood that the market was not a substitute for the messy business of living together.

My little experience within corporations shows them to remain thoroughly political. There are all kinds of intra-corporate groups, both formal and informal. And there is all kinds of negotiation that has to happen among them. Of course the bottom line is always the bottom line. But because there is no given, simple, or determined path to profit maximization, and there are no rational utility maximizers continually action as though they were engaged in exchange, all kinds of negotiations among groups have to take place.

Also, the quantitative ‘real’ does not exist, except as a problematic statistical construct. That construct is meaningful and affective because of the way it is deployed. But it is not a representation of output or well-being, distorted or otherwise. As for what that measure supposedly relates to ‘actual production’, that remains incredibly important. I agree that nominal concerns dictate. But production has a lot to say. An area of CasP research that needs more work is the relationship of production with the structures of ownership. CasP undermines productivism–the perspective on accumulation that considers production determinant–and, as such, research has tended to look away from production to other social forces that are relevant for accumulatory outcomes. But it does not deny the importance of production.

Thanks for the prompts to thinking of these things, even if I disagree with your suppositions!

-

May 22, 2021 at 12:39 am #245678

Perhaps we are talking past each other here.

While I believe the politics v. economics duality is LITERALLY false, I also believe it has been made true as practical matter and serves to perpetuate the power of capital, which springs from the delegation of the sovereign power over the control of the money supply. Finance would not wield the power of capital but for governments ceding that portion of their domain.

I also believe the idea that the “nominal” is a reflection of the “real” is literally false, but, as a practical matter, the real/nominal duality is made true as a practical matter when expressed as CasP theory predicts it: finance drives (has power over) the “real” economy.

When you possess power, confidence in obedience trumps literal truth. From this perspective, the outright rejection of these foundational false dualities prevents CasP from fully understanding the source and nature of capital’s power.

In a way, I am applying Philip Miroswski’s concept of the “Double Truth Doctrine” of neoliberalism, which entails the same statement having one truth for the elite (the rulers), and another truth for the masses (the ruled). Can these basic dualities be expressed in CasP terms in a way that makes them true for the rulers, even though it is obvious that these dualities are false with respect to the ruled (who cannot see that fact)?

Even Plato’s Noble Lie could never be made literally true, but his point was that as long as the ruled believe it be true, that is enough for the rulers to be confident in their obedience, i.e., the lie itself is a major source of the rulers’ power.

-

-

May 22, 2021 at 12:10 pm #245680

From this perspective, the outright rejection of these foundational false dualities prevents CasP from fully understanding the source and nature of capital’s power

I’m not sure I understand your claim. Perhaps you can use the following example to illustrate it.

In our work, we suggested that, during the second half of the 20th century, the Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition supported Middle-East Energy Conflicts to boost its differential accumulation-read-power (for example, ‘New Imperialism or New Capitalism?’ 2006, http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/203/).

Do you think that ignoring the presumable politics-economics duality here prevented us from understanding the power of this coalition?

***

To clarify, we do not ‘reject’ the politics-economics duality. As we reiterate in our work, this duality is inherent in the way capitalism is framed virtually by all observes (except CasPers, maybe). Instead, we argue that, when it comes to the actual processes of accumulation, this duality has no operational meaning in the sense that capital discounts all forms of power, regardless of the specific rubrics they are hashed into.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

May 22, 2021 at 2:32 pm #245682

I’m not sure I understand your claim. Perhaps you can use the following example to illustrate it. In our work, we suggested that, during the second half of the 20th century, the Weapondollar-Petrodollar Coalition supported Middle-East Energy Conflicts to boost its differential accumulation-read-power (for example, ‘New Imperialism or New Capitalism?’ 2006, http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/203/).

Do you think that ignoring the presumable politics-economics duality here prevented us from understanding the power of this coalition?

Thank you for your question. I hope I can answer it to your satisfaction, but I am an electrical engineer and lawyer by training, not a linguist or philosopher, and that is the kind of domain into which I am heading.

I did not say that you “ignored the presumable politics-economics duality,” I said you rejected it. In doing so, you engaged its literal meaning, which is the opposite of ignoring the duality altogether. Clearly, your engagement with the politics-economics duality and other foundational assertions of capitalism yielded CasP theory, which was a great achievement.

But CasP theory is not complete, as you and Shimshon Bichler discussed in a 2018 paper. While I agree with most, if not all, of CasP’s assertions, I think they need to be extended and restated to be more complete. For example, I think Tim DiMuzio’s conclusions regarding money and debt need to be more fully integrated into CasP theory proper as it is the delegation of the sovereign power of money to private parties that is the ultimate source of capital’s power, e.g., as I’ve said elsewhere on this forum, it is private control over money, wages and prices that gives rise to the “depth regime” of sabotage.

I started this thread because it seems that the foundational assertions of capitalism have meaning and purpose beyond those engaged so far by CasP. The politics-economics duality, although false factually, has nevertheless become true normatively. Thus, the politics-economics duality is not simply what it “means,” it is also what it “does.” From what I have seen so far, CasP has engaged the former, not the latter, but correct me if I am wrong. The real-nominal duality also “does” something, but its function is different than that of politics-economics. Regardless, both of these foundational assertions are part of the architecture of capital’s power, and understanding them within the context of their function within that architecture is distinct from whether or not they are accurate statements.

The fact that Plato discussed the concept of foundational assertions as Noble Lies (or true falsehoods) thousands of years ago within the context of discussing the establishment of a social power hierarchy demonstrates that power cares about what foundational assertions do, not whether they are true. Understanding what such assertions do may lead to a deeper understanding what power cares about (or fears).

-

May 22, 2021 at 6:17 pm #245683

[…] it is the delegation of the sovereign power of money to private parties that is the ultimate source of capital’s power, e.g., […] it is private control over money, wages and prices that gives rise to the “depth regime” of sabotage.

Thank you Scot for the clarification.

I think there is a certain tautology to your argument. You say, and I paraphrase a bit, that the privatization of money is an important if not the ultimate source of capital’s power. You can similarly say that the private control of pharmaceuticals, energy, transportation, entertainment, construction, agriculture, biotechnology, education, advertisement, religion and what not are also sources of capital’s power.

According to CasP, capital is private by definition, so for something to become capital, it must first be privately owned.

Regarding the argument that the privatization of money creation is the ‘source’ of capital’s power.

(1) I think the issuance of money is never entirely private; like all forms of private power, it too is always backed by and intertwined with some form of governmental agency. Without this fusion, private money is bound to collapse (think of the early princely bonds issued by medieval rulers to private investors, or speculate what will happen to the U.S. private banking system without government oversight and backup).

(2) Conceptually and ontological, fiat money is based on forward-looking credit: i.e., the capitalization of risk-adjusted expected future returns. To get the process of money creation going, private banks have to issue loans, and these loans are nothing but capitalized profit expectations. In this sense, the modern system of money is a derivative of capitalization, not its cause. And if this argument is correct, the privatization of money cannot be thought of as the ‘source’ of capital’s power.

(3) More generally, in our opinion (Shimshon’s and mine), power has no single ‘source’, or ’cause’, let alone an ultimate one. In modern times — say since 1600 — power is considered a quantified relationship between entities. In society, these quantified relationships are creordered by human beings and organizations through various hierarchies of sabotage and resistance. Increasingly, these powers appear as as differential relations of capitalization/credit (including the institution of fiat money), but this appearance is not a cause, at least not in our opinion. It is merely the ‘operational symbol’, in Ulf Martin’s language, the quantified ritual with which modern capitalism expresses and negotiates its various hierarchies. At any given time, these symbols serve restrict and condition the boundaries of the possible, but they are also incredibly flexible, so that, over time, they can accommodate ever new forms of hierarchical power.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

May 23, 2021 at 10:44 pm #245688

Thank you for the expansive reply, Professor Nitzan. It will take me some time to think though all that you said, but I have some initial reactions to some of what you said.

When I say that the private control of the money supply is the “ultimate” source of capital’s power, I mean the “original,” “first” or “fundamental.” I don’t mean to imply that it is the “sole” or “most important” source of capital’s power. Indeed, elsewhere on this forum, I have referred to secondary sources of capital’s power, which combined control the breadth regime of sabotage, i.e., capital’s indirect control over wages, prices, and profit expectations of publicly traded corporations.

Regardless, in terms of timing, money supplies existed long before equity and debt markets, which I believe Finance created as a way to increase the value of existing capital without directly affecting the money supply (i.e., equity and debt markets were created to ensure differential accumulation), a fact that further cements the primacy of Finance’s control of the money supply in terms of creating and sustaining its power.

Finally, fiat money is not the issue, credit money is. As Di Muzio and others have documented, credit money– which is the system we have– obviates the entirety of paragraph (2) of your latest response because a commercial lender puts no existing capital or money at risk when it extends interest-bearing credit to a “borrower,” which is why I have come to call the process of paying off a loan “immaculate accumulation” because the bank accumulates tax-free capital worth more than 100% of the credit it granted, something the government could have done for simply the cost of repaying the full amount of the credit (whereupon repayment would remove the money from circulation, thus preventing any monetary inflation). Di Muzio has argued that credit money is what drives the need for the perpetual exponential growth of credit, money end economic growth, as well as “differential accumulation” more broadly. And he is right.

P.S. I believe the discussion of “rituals” and “symbols” (and “COP-MOP” pairs) makes it more difficult to understand CasP and its value in providing a framework for describing Capitalism as a control system. Besides, deception is Capitalism’s primary “concept of power,” and it is already hard enough for many to accept the fact of that deception let alone look past it to map the architecture of Capitalism as control system (CaCS?), which I guess is what I am trying to do. Anyway, thank you again for engaging with me. Your thoughtful responses are always helpful and challenging in a positive way.

-

May 24, 2021 at 8:17 am #245689

Thank you Scot.

fiat money is not the issue, credit money is.

Yes, the issue is credit/debt money, but the system of credit/debt money cannot exist with commodity money. It needs fiat money – money by decree — as its denominator.

a commercial lender puts no existing capital or money at risk when it extends interest-bearing credit to a “borrower,”

I’m not sure I follow. Loans and the interest on them — including those made by commercial banks — are expected to be paid in the future. The fact that borrowers may not repay them makes these ‘extensions’ risky. This risk is mitigated by different forms of power, including government backing of the private banking system, but to say it does not exist seems to me odd given the nature and turbulent history of credit and banking more specifically. (Perhaps you mean that banks lend other people’s money rather than their ‘own capital’, but that fact makes them no less risky.)

credit money is what drives the need for the perpetual exponential growth of credit, money end economic growth, as well as “differential accumulation” more broadly

We’ll have to disagree on that. In my view, credit money is a facet of capitalization, not the other way around.

the discussion of “rituals” and “symbols” (and “COP-MOP” pairs) makes it more difficult to understand CasP and its value in providing a framework for describing Capitalism as a control system

Needless to say, you are welcome to offer easier-to-understand explanations!

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

May 24, 2021 at 3:53 pm #245694

Thank you Scot.

a commercial lender puts no existing capital or money at risk when it extends interest-bearing credit to a “borrower,”

I’m not sure I follow. Loans and the interest on them — including those made by commercial banks — are expected to be paid in the future. The fact that borrowers may not repay them makes these ‘extensions’ risky. This risk is mitigated by different forms of power, including government backing of the private banking system, but to say it does not exist seems to me odd given the nature and turbulent history of credit and banking more specifically. (Perhaps you mean that banks lend other people’s money rather than their ‘own capital’, but that fact makes them no less risky.)

How does one “repay” something that was never “paid” to him in the first place?

To extend credit, banks do not loan existing money or capital, i.e., they do not debit one account and credit the “borrower’s” account with the same amount. Rather, in exchange for the borrower’s promise to pay the amount to be credited with interest, the bank enters a few key strokes to make that the amount appear in the borrower’s account. Loans create deposits. Thus, nothing of the bank’s or its depositors is put at risk in the act of extending credit.

The “risk” of nonpayment only arises because banks account for the obligation to pay for the credit as if existing funds were transferred to the borrower, but that is not the case. Under accounting rules, the act of extending credit upon the promise of of payment with interest results in the creation of an asset on the bank’s balance sheet equal to the credit amount with interest. The value of that fictional asset, and the entire credit transaction, arise from the borrower’s promise to pay and nothing else, but that is the price the bank demands for exercising the state’s power of money creation, which the state could do at no cost and without requiring the payment of interest in a manner in which no capital would accumulate because paying the government effectively destroys money.

Here are couple of useful links regarding how credit money differs from the loanable funds theory and fractional reserve theory of banking, including a brief talk from Steve Keen. The Google Docs link provides the most succinct summary of how banks create money.

https://www.smartsurvey.co.uk/s/RE_RROB_OpenLetter/

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1LUTAipMOfUupGdde3mLy57yVhhruP-gFxXpvonazjao/edit

credit money is what drives the need for the perpetual exponential growth of credit, money end economic growth, as well as “differential accumulation” more broadly

We’ll have to disagree on that. In my view, credit money is a facet of capitalization, not the other way around.

The only thing credit money capitalizes is the borrower’s labor as it is the promise of payment that becomes the bank’s capital asset as the bank’s price for exercising the state’s power of money creation. No corresponding capital asset existed before credit was extended to the borrower. When capitalism is based on credit money, all money and capital begins as indentured servitude.

the discussion of “rituals” and “symbols” (and “COP-MOP” pairs) makes it more difficult to understand CasP and its value in providing a framework for describing Capitalism as a control system

Needless to say, you are welcome to offer easier-to-understand explanations!

Working on it! I am test-driving some initial thought on this forum.

-

May 24, 2021 at 8:47 pm #245695

Thanks for the interesting reply, Scot.

1. Bank-originated money. Thank you for the links. I’m familiar with these claims, though I’m not sure how they affect our exchange here. Yes, private banks can create deposits and loans in one fell swoop, but this ability has no bearing on the fact that the loans – be they to corporations, NGOs, governments or individuals – are eventually withdrawn from the accounts in order to be utilized; that they have to be repaid with interest in the future; and that occasionally they are not. Isn’t this last fact a risk for the banks?

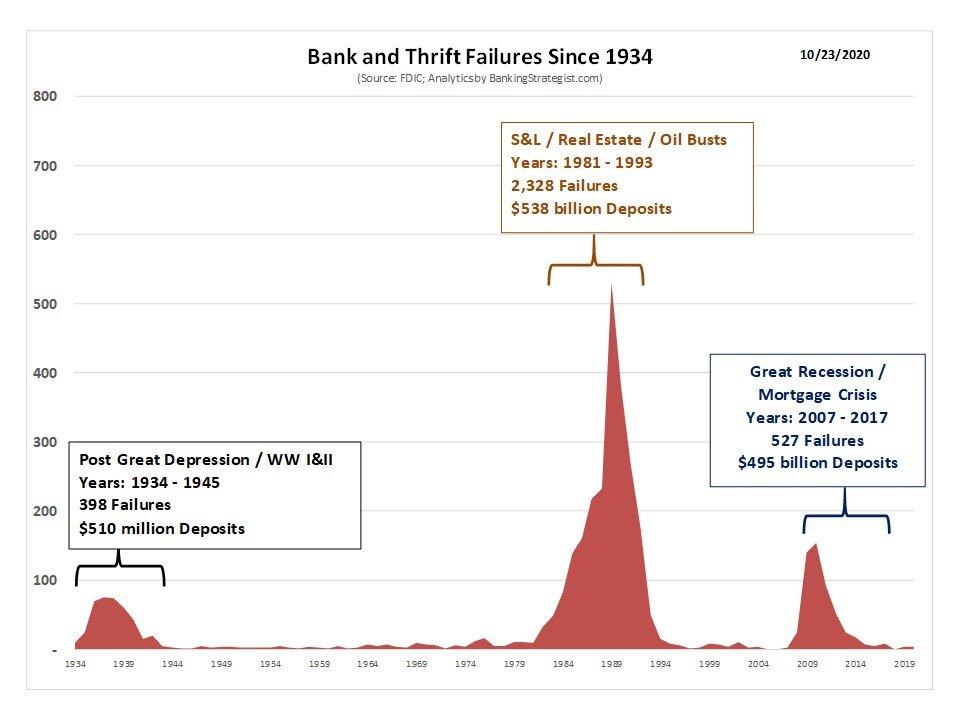

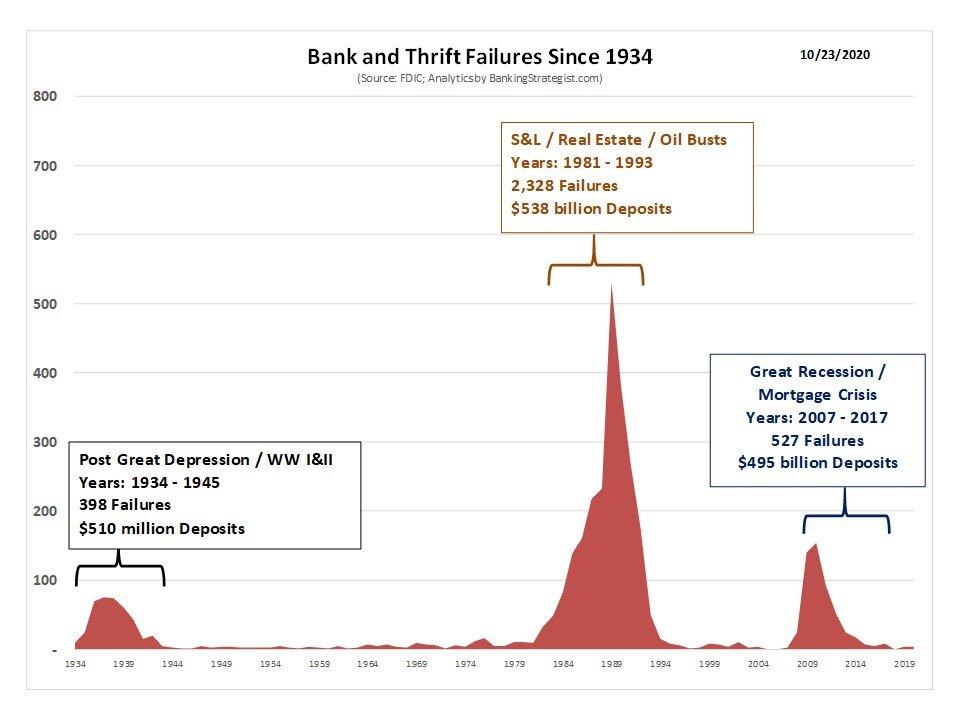

2. The facts. Over the past two centuries, banking crises affected between 5-30% of all countries on an ongoing basis (first figure). In the U.S., banks fail all the time – and occasionally, they fail spectacularly (second figure). Aren’t these crises and failures evidence that banks are risky?

[1] Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2008. This Time is Different: A Panoramic View of Eight Centuries of Financial Crises. March. NBER Working Paper Series (13882): 1-124. https://www.nber.org/papers/w13882

[2] https://www.bankingstrategist.com/history-of-us-bank-failures

3. Capitalization. The act of capitalization does not occur in the balance sheet, which is backward-looking. It happens in the equity/debt market which is forward-looking. In this sense, banks are like every other corporation: their ultimate goal is to augment their capitalization by raising their discounted risk-adjusted expected income. That’s why corporations, including banks, are in business.

4. Balance sheets. The balance sheets of banks are similar to those of non-bank corporations in that their owners/managers can enlarge them, often at will. Non-bank corporations can do it by borrowing and/or issuing stocks; banks can do it by issuing stocks but mostly by extending loans against deposits (external or self-created). In both cases, the expansion occurs because the owners/managers think it will increase their expected risk-adjusted earnings. But neither banks nor other corporations expand their balance sheets without end. And why not? Because debt leverage and equity dilution are risky.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

May 24, 2021 at 11:35 pm #245699

Thanks for the interesting reply, Scot. 1. Bank-originated money. Thank you for the links. I’m familiar with these claims, though I’m not sure how they affect our exchange here. Yes, private banks can create deposits and loans in one fell swoop, but this ability has no bearing on the fact that the loans – be they to corporations, NGOs, governments or individuals – are eventually withdrawn from the accounts in order to be utilized; that they have to be repaid with interest in the future; and that occasionally they are not. Isn’t this last fact a risk for the banks?

There is always a risk of nonpayment, but the banks put nothing of their own (or their depositors’) at risk, and a simple change of the accounting rules could eliminate that “risk,” which the banks only take on because (1) banks don’t want to pay taxes on the “principal” that they did not put at risk in the first instance, and (2) banks want to be able to claim the loans as assets they can use as collateral. Again, the core COP of capitalism appears to be deception.

2. The facts. Over the past two centuries, banking crises affected between 5-30% of all countries on an ongoing basis (first figure). In the U.S., banks fail all the time – and occasionally, they fail spectacularly (second figure). Aren’t these crises and failures evidence that banks are risky? [1] Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2008. This Time is Different: A Panoramic View of Eight Centuries of Financial Crises. March. NBER Working Paper Series (13882): 1-124. https://www.nber.org/papers/w13882 [2] https://www.bankingstrategist.com/history-of-us-bank-failures

Yes, Finance creates a lot of risks for itself, and when it loses its bets, society as a whole pays for it. That does not mean that any lending of existing capital/money occurs when banks “loan” money into existence. The Gold Standard never really restrained the Bank of England, for example, who triggered the Long Depression by making bad bets on American railroads in excess of what the Gold Standard allowed (it has been about a decade since I read the late 19th early 20th century text that makes that point, but I can find it again).

I recently read Richard Vague’s A Brief History of Doom: Two Hundred Years of Financial Crises, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. (I threw away my hardcover Reinhart and Rogoff a long time ago.) While Vague rightly focuses on excessive private commercial debt as a harbinger of a financial crisis, that debt is usually tied in some way to stock market speculation, i.e., (using a Ghostbusters reference) Finance decided to “cross the streams,” and disaster ensued.

The irony is that banks initiate cascading financial crises not by extending credit to speculators in the first place, but by calling for speculators’ loans to be paid in full when certain money liquidity covenants are triggered. It is the lender’s insistence on being paid in money (as opposed to using other capital assets) that results in fire sales of capital assets that trigger other speculator’s covenants, causing the whole thing melts down.

3. Capitalization. The act of capitalization does not occur in the balance sheet, which is backward-looking. It happens in the equity/debt market which is forward-looking. In this sense, banks are like every other corporation: their ultimate goal is to augment their capitalization by raising their discounted risk-adjusted expected income. That’s why corporations, including banks, are in business.

I disagree with CasP’s definition of capitalization because it does not apply to all capital assets, only stocks. For example, bank deposits, which are a form of capital, are priced by their nominal value. Similarly, the price of a bond can vary even though its yield is known because that yield is less than or more than the prevailing yield of similar bonds (i.e., bond prices reflect discounts or premiums based on whether they have negative or positive differential accumulation with respect to other bonds of the same class and maturity). I have developed my own definitions of capital and capitalization to address all capital assets in a manner that otherwise remains consistent with CasP.

4. Balance sheets. The balance sheets of banks are similar to those of non-bank corporations in that their owners/managers can enlarge them, often at will. Non-bank corporations can do it by borrowing and/or issuing stocks; banks can do it by issuing stocks but mostly by extending loans against deposits (external or self-created). In both cases, the expansion occurs because the owners/managers think it will increase their expected risk-adjusted earnings. But neither banks nor other corporations expand their balance sheets without end. And why not? Because debt leverage and equity dilution are risky.

Balance sheets are very important to Capitalism and may be an innovation that was even more important to the rise and survival of Capitalism than the modern corporation.

But much (if not all) of the risk on banks’ balance sheets is created by the banks’ insistence that banks get to treat the non-existent loan principal they conjure into existence as already-existing capital/money the banks put at risk so the banks can accumulate payments of principal without paying taxes (“immaculate accumulation”). That is, the banks create and embrace the risk to ensure their own differential accumulation. This risk, which is of their own creation, is only exacerbated by the banks’ refusal to accept capital assets other than money deposits as satisfaction of called loans. As a result, I have less than zero sympathy for commercial banks and believe they need to be reduced to public utilities.

By the way, today I started reading your 1992 Ph.D thesis, which is pretty impressive. Given that neoclassical economics insists that power is exogenous to the economy and economics, I just don’t understand how you came to embrace your intuition that inflation is a form of restructuring, i.e. the assertion of power. Trying to quickly follow the through line between your thesis and the 1998 article introducing the concept of differential accumulation did not help me figure out why you chose to take a path so orthogonal to your home academic discipline. I classify CasP as straight up political philosophy or political science, not political economy or economics. Capitalism transcends prior conceptions of the state as it is agnostic to and capable of subsuming/subordinating all of them by rendering them as little more than bread and circuses for the masses.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 8 months ago by Scot Griffin.

-

May 25, 2021 at 11:43 am #245701

Let me summarize my understanding of your reply (and add a few comments/observations):

1. Banks do face a repayment risk, but this risk can be eliminated (though I’m not sure I understand how they can eliminate it without foregoing or undermining their expected profit).

2. Finance (banks?) creates risk primarily by making ‘bad bets’ (isn’t this true of all capital?).

3. Financial crises are associated mainly with speculation. Finance often initiates these crises through its relation with speculators — but this initiation happens not because it lends to speculators per se, but because it insists they repay their debt — and in ‘hard cash’ to boot (Isn’t all investment/lending ‘speculative’ – i.e. future dependent? Isn’t debt always a ‘collectable asset’ until capitalists realize/admit it isn’t?)

4. My comments suggest that the topic we deal with is both technical and theoretically foundational to negotiate cryptically as we have done here.

5. Your question about my dissertation: perhaps you’ll figure the answer after reading it.

6. “I classify CasP as straight up political philosophy or political science, not political economy or economics”. That’s your prerogative.

7. I look forward to seeing your ideas articulated in a systematic piece!

-

May 25, 2021 at 1:06 pm #245702

7. I look forward to seeing your ideas articulated in a systematic piece!

Me, too! Our conversation is helping me understand how to present my ideas better within the CasP framework. I recognize that I often tend to present my ideas in an idiosyncratic way, so gaining a deeper understanding of your theory directly from you should help me “normalize” my presentation.

Let me summarize my understanding of your reply (and add a few comments/observations): 1. Banks do face a repayment risk, but this risk can be eliminated (though I’m not sure I understand how they can eliminate it without foregoing or undermining their expected profit).

Yes, banks do face the risk of nonpayment, but what does that risk really entail and why do they incur it?

Until recently, mainstream economists (including Milton Friedman and Paul Krugman) and central banks insisted that banks acted merely as intermediaries between savers and borrowers, a theory that supported the assertion that economics need not consider money or banks in its models.

Now, central banks openly admit that commercial banks conjure money into existence when they extend credit.

Legally and from an accounting perspective, there ought to be consequences for this admission. First, legally, for years banks committed accounting fraud by claiming to have loaned existing money/capital, which is what allowed them to accumulate the principal tax-free. That’s not “profit,” that’s a form of theft. Second, we know nothing will happen legally, but the accounting rules should be changed, at the very least, to disallow “loans” to be treated as assets except to the extent payments have actually been received. That simple change would not affect the banks’ profits at all, just the timing of if and when those profits accrue as assets on their balance sheets. Personally, I don’t think that goes far enough, as the extension of principal is really the creation of money, a sovereign power. Either (1) banks should not extend credit at interest but instead share an origination fee of 5-15% of the principal as it is repaid, or (2) if lending at interest should continue, 100% of the principal should be taxed while leaving the taxation of interest as it currently is (which would make everybody’s understanding of bank profits true, i.e., banks only profit from the interest, not the principal).

If capital is power, credit money as it currently exists is power laundering through immaculate accumulation.

2. Finance (banks?) creates risk primarily by making ‘bad bets’ (isn’t this true of all capital?). 3. Financial crises are associated mainly with speculation. Finance often initiates these crises through its relation with speculators — but this initiation happens not because it lends to speculators per se, but because it insists they repay their debt — and in ‘hard cash’ to boot (Isn’t all investment/lending ‘speculative’ – i.e. future dependent? Isn’t debt always a ‘collectable asset’ until capitalists realize/admit it isn’t?) 4. My comments suggest that the topic we deal with is both technical and theoretically foundational to negotiate cryptically as we have done here. 5. Your question about my dissertation: perhaps you’ll figure the answer after reading it. 6. “I classify CasP as straight up political philosophy or political science, not political economy or economics”. That’s your prerogative.

Thanks again for your comments. I am in the middle of writing an essay that I initially hoped to submit for the RECASP competition earlier this year, but I have been struggling with the proper scope of the endeavor. Our conversation has helped me to narrow things down. I should be able to respond to your comments in that essay, hopefully sometime in June.

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.