- This topic has 9 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated May 14, 2021 at 4:15 pm by .

-

Topic

-

MMT is inarguably the most visible heterdox economic framework. One of its foundational speakers, Randy Wray, spoke at the second (I think) Capital as Power conference. Unfortunately, I did not fully grasp his argument at the time.

I have since engaged more with MMT writings, in part because of the prominence of MMT and its proponents on social media. It opened my eyes to some pretty central functions of fiscal and monetary operations. It strikes me that the creation of money is vital to the processes of differential accumulation. Further, the process of DA is the central dynamic of capitalism, and therefore important to processes of money-creation.

I think that engagement between the framework and concepts of MMT and that of CasP could be fruitful, even if the two cannot fully concord. Doing science being eschewed loyalty to an analytical toolbox. Bringing MMT and CasP together should leave us with more insights and better analytical tools.

Two immediate questions and considerations have come to me: inflation & equity as money.

Inflation & Redistribution

CasP and MMT have converging and diverging insights is inflation. Both view price movements as institutional rather than mechanical. I know that some MMT proponents are familiar with Means important work on administered prices, as well as the work of Hall & Hitch.

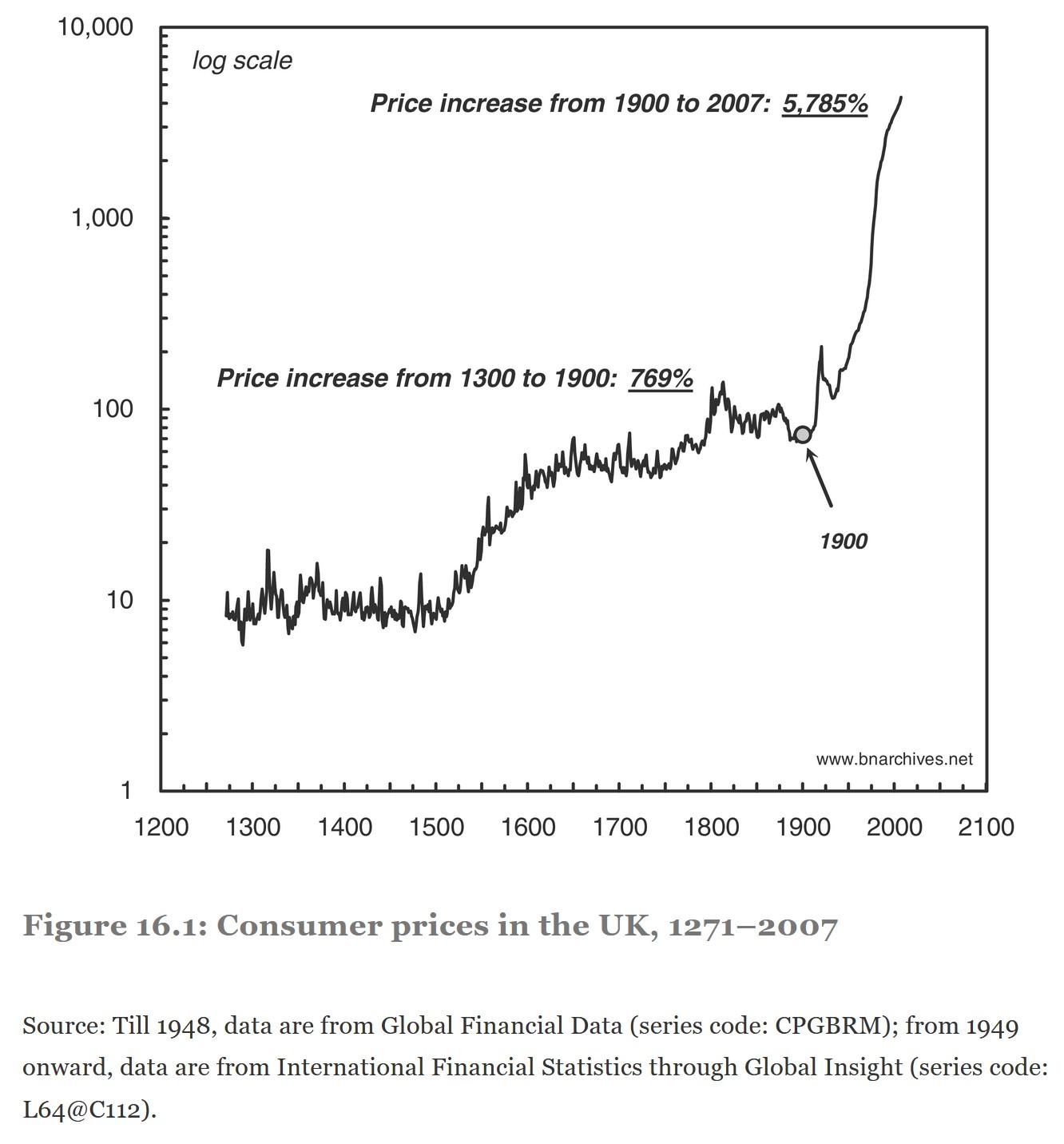

MMT focuses on aggregate level inflation, because it talks about the tools of money creation and destruction as means to manage inflation. N&B have twisted Friedman’s famous comment to observe that inflation is everyone, and always, redistributionary, which emphasizes sub-aggregate price changes. One policy prescription that has come out of MMT is to create enough money to push up inflation, perhaps even beyond the 2% target of most central banks. It is well-known that higher inflation benefits debtors at the expense of creditors. N&B, however, have shown that higher inflation has tended to differentially benefit dominant capital. Can this seeming conflict be resolved? Perhaps it is the difference between aggregate and differential (i.e. sub-aggregate) analysis.

There is not actually any such thing as aggregate inflation. We have invented aggregate measures to inform macroeconomic analysis and management, for better or worse. Of course, those measures have been reified with the emphasis on so-called ‘real’ measures of the economy. However, it seems that MMTers are well aware of the problems with real measures, so their use of aggregate inflation measures seems to be done with full awareness that they are manufactured and inherently problematic. What insights might be added to MMT if its analytical lens was trained on the use of prices as part of a redistributionary struggle?

Are corporate equities money?

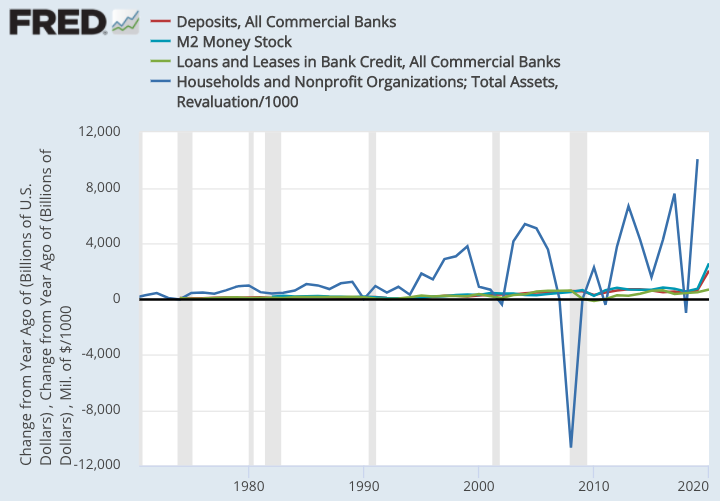

One of the threads of MMT is where money comes from. It focuses on currency sovereign governments ability to spend money into existence. A criticism has been that it downplays, or even ignores, the money-creation ability of private banks. One recent part of this argument is that private banks are effectively franchisees of the central bank, which is analytically rolled into the government. However, a question that has emerged for me is: Are corporate equities money? I posed the question on Twitter to some MMT folks. Their offhand response was ‘no.’ My inclination is ‘yes.’ An important part of my effort to understand equities as money is the marginal process of equity valuation. If a company has one million shares, valued at $100/share, for a total valuation of $100 million, and then a single share sells for $200, that means the valuation jumps to $200 million. Has the total amount of money in the economy doubled? It seems that equities are not the same bank deposits. But they also don’t seem to be NOT money. If I were more skilled at using Godley Tables, which are another key part of MMT, I might be better able to resolve this matter.

What are other folks thoughts about MMT and its potential to work together with, or potentially against, CasP?

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.