Home › Forum › Political Economy › “Money creation” and income redistribution

- This topic has 10 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated November 15, 2022 at 4:39 pm by Rowan Pryor.

-

CreatorTopic

-

November 12, 2022 at 2:21 pm #248578

We received the following question from an economics professor:

Dear Jonathan,

[…] I come from “mainstream econ” but, with time, I have become increasingly critical of the mainstream dogma. I enjoyed reading your book “Capital as Power” and I have a question related to your “inflation as redistribution” graphs on pages 371 and 373.

The recent “Nobel prize” in Economics seems to emphasize banks’ role as intermediaries who merely receive money from depositors and channel it to borrowers. The reality is that they are producers of purchasing power (as noted by Schumpeter).

I wonder whether one can think of money creation as redistribution in much the same way as you thought of inflation as redistribution in the above-mentioned graphs. In other words, is it possible to plot your differential markup (resp., the ratio of corporate earnings per share to the wage rate) together with some measure of money creation? The question, of course, is whether these series are positively correlated.

Is this a sensible question? If so, would your theory be able to shed some light on the relationship between money creation and redistribution?

Thanks.

Here is a tentative reply:

1. For simplicity, let’s assume that:

bank profits = lending rate * loans – deposit rate * deposits – cost of operation

2. If loans and deposits move more or less in tandem, and if the cost of operation is relatively stable, bank profitability will depend mostly on the lending-deposit spread.

3. We haven’t studied this question empirically, but my hunch is that the lending-deposit spread could very well be negatively correlated with money growth.

4. If conjecture 3 is correct, it follows that when the money supply grows, bank profits (as well as their share in overall profit) will expand due to the growth of money but contract due to the accompanying compression of the spread, leaving the net effect uncertain.

It will be interesting to see someone examining this question empirically for a number of countries.

- This topic was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

November 12, 2022 at 9:33 pm #248581

We received the following question from an economics professor:

Dear Jonathan, […] I come from “mainstream econ” but, with time, I have become increasingly critical of the mainstream dogma. I enjoyed reading your book “Capital as Power” and I have a question related to your “inflation as redistribution” graphs on pages 371 and 373. The recent “Nobel prize” in Economics seems to emphasize banks’ role as intermediaries who merely receive money from depositors and channel it to borrowers. The reality is that they are producers of purchasing power (as noted by Schumpeter). I wonder whether one can think of money creation as redistribution in much the same way as you thought of inflation as redistribution in the above-mentioned graphs. In other words, is it possible to plot your differential markup (resp., the ratio of corporate earnings per share to the wage rate) together with some measure of money creation? The question, of course, is whether these series are positively correlated. Is this a sensible question? If so, would your theory be able to shed some light on the relationship between money creation and redistribution? Thanks.

Here is a tentative reply: 1. For simplicity, let’s assume that: bank profits = lending rate * loans – deposit rate * deposits – cost of operation 2. If loans and deposits move more or less in tandem, and if the cost of operation is relatively stable, bank profitability will depend mostly on the lending-deposit spread. 3. We haven’t studied this question empirically, but my hunch is that the lending-deposit spread could very well be negatively correlated with money growth. 4. If conjecture 3 is correct, it follows that when the money supply grows, bank profits (as well as their share in overall profit) will expand due to the growth of money but contract due to the accompanying compression of the spread, leaving the net effect uncertain. It will be interesting to see someone examining this question empirically for a number of countries.

When it comes to money creation through bank loans, we should probably be talking about the distribution of power, not the redistribution of income.

Consider a bank “loan” in isolation. Banks do not lend money, they create money in exchange for the debtor’s promise to pay that money plus interest to the bank at a later time.

When the debtor pays off the “loan,” the interest is treated as profit, but how is the “principal” that has been “repaid” treated? Is it extinguished along with the debtor’s legal obligation to pay the principal, or does it accrue as a “return” of the bank’s capital on the assets side of its balance sheet (i.e., is the capital of the loan obligation transformed into reserves as principal is repaid)? To calibrate, principal payments made on loans extended by non-banks are treated as the return of capital and carried as an asset but not taxed as income.

Steve Keen and MMTers argue that since the repayment of bank debt destroys money, the only thing the bank has on the assets side of the balance sheet when the debt is paid is the interest, which as taxable as profits.

While I agree that paying bank debts destroys money, money is by definition on the liabilities side of the bank’s balance sheet, so the fact that “money is destroyed” does not tell us anything about what happens on the assets side of the balance sheet.

The way I understand Steve’s argument, it is the double-entry nature of accounting that enforces destruction of the “repaid” capital on the assets side of the balance sheet. The problem with his argument, and the likely reason for the continued existence of the empirically false loanable funds theory of banking (which claims banks are merely intermediaries who shuttle money from depositors to debtors), is the accounting rules and tax laws treat the stated amount of principal of the debt obligation as if it were capital that existed at the time of the bank loan such that the the payment of principal is treated as a return of the bank’s capital and not subject to taxation. In other words, when it comes to bank loans and their repayment, there is more than one accounting rule in operation.

I am not an accountant, but I have worked closely with accountants over the years in preparing financial reports for the SEC and investors, and I have made a serious effort to find relevant accounting rules that support Steve’s argument, to no avail. I have also asked him and anyone who knows to point me to applicable accounting rules, but they have not been able to do so.

If such a rule existed, it should be easy to find. Why? Because the rules would distinguish between two types of loans: (1) bank loans that did not involve the transfer of existing funds; and (2) all loans by non-banks, which require the transfer of existing funds. To the extent such accounting rules exist (and they do, at least with respect to how to mark-to-market the value of the loan), they treat the repayment of principal the same, i.e., there’s no rule that says banks must write-off/destroy the principal as it is repaid (even as the legal obligation of repayment is debited), and, if there were, the market value of any bank loan for accounting purposes must always be zero (even though the legal obligation to pay the principal plus interest remains). Indeed, absent the likelihood of default, accounting rules recognize the unpaid principal amount of bank loans held for their duration as their market value on the books. Accounting rules treat bank loans held for sale differently because the secondary market (e.g., for home mortgages) prices each individual loan at, below, or above the unpaid principal amount.

The existence of secondary markets for bank loans and credit collection agencies further argue against the notion that the end-value of repaid principal is null.

If principal payments accrue as the return of capital, bank money creation results in the banks’ “immaculate accumulation” of capital.

If principal payments somehow evaporate into nothingness (if so, I really would like somebody to explain how that is the case; I want to be proven wrong), it might be informative to spend some time with the specifics of how banks report income. If BofA and Wells Fargo are indicative of the banking industry as a whole, all US banks report income as “net interest income” and “non-interest income.” Net interest income nets out interests paid on deposits and therefore reflects the “spread” you discuss above. You will see that non-interest income is on the same order of magnitude for both BofA and Wells Fargo.

Regardless, instead of trying to measure whether money creation redistributes income, it would probably be easier to consider annual debt service as a percentage of GDP and/or annual money creation relative to annual debt service. NOTE: It would be better to consider net debt service (debt service minus interest payments), but I have not been able to figure out how to isolate interest payments from the Fed Flow of Funds data.

-

November 12, 2022 at 11:29 pm #248586

I once used Emmanuel Saez’s data along with IRS data to calculate debt-to-wage ratios for the top decile and the bottom 90%. (I avoided using BEA data due to its use of fictitious imputations.)

-

-

November 12, 2022 at 9:36 pm #248582

Regarding my point (2) above, here are the weekly data for deposits and credit in the U.S. banking system — first in levels ($bn) and then in annual rates of change (%).

Loans and deposits do move in tandem.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

November 13, 2022 at 7:19 pm #248592

Demand Deposits, which are the component of M1 most tied to money creation (which is created to spend, not save), is probably a better series than all Deposits. Similarly, you probably want Loans and Leases in Bank Credit, which excludes treasuries, mortgage-backed securities, and other securities held by banks, instead of all Bank Credit.

-

November 13, 2022 at 10:23 am #248587

money is by definition on the liabilities side of the bank’s balance sheet

There are two kinds of ‘money’ in operation here. One is ‘credit money’ which sits on the liabilities side. The second is ‘currency money’ (which originates from a central bank loan or from the bank owners equity) and it sits on the assets side (reserves). Let’s just agree to call it currency for now.

As I understand it, the argument (by Keen, et al.) is as follows – The books need to be kept balanced at any time and after each monetary occurrence by a double-entry procedure:1: New loan [+ Asset (loan)]–>new deposit [+ Liabilities]

2: Deposit leaves the bank [- Liabilities]–> currency leaves the bank [- Assets (reserves)]

3: interest paid on the loan: currency flows to the bank [+ Assets (reserves)] –>profit registered for owners [+ Liabilities (equity)]

4: principal returns [- Assets (loan “write-off”)]–>currency returns to the bank [+ Assets (reserves)]This is a simple example involving all of the recorded credit money leaving the bank (so all of the currency corresponding to the loan/deposit figures needs to be employed). But a similar procedure can be described for the extreme counter example (all recorded credit money stays in the bank, so no need for currency transfers).

In my opinion, this is the only explanation that makes sense. Registering the returned principal as a net asset would violate accounting rules since it would register twice on the asset side (as currency and as “write-off loan money”), resulting in the need for recording a third monetary occurrence (crediting equity out of the blue) with no corresponding double-entry registration. Or else the books will not stay balanced.

-

November 13, 2022 at 12:20 pm #248588

money is by definition on the liabilities side of the bank’s balance sheet

There are two kinds of ‘money’ in operation here. One is ‘credit money’ which sits on the liabilities side. The second is ‘currency money’ (which originates from a central bank loan or from the bank owners equity) and it sits on the assets side (reserves). Let’s just agree to call it currency for now. As I understand it, the argument (by Keen, et al.) is as follows – The books need to be kept balanced at any time and after each monetary occurrence by a double-entry procedure: 1: New loan [+ Asset (loan)]–>new deposit [+ Liabilities] 2: Deposit leaves the bank [- Liabilities]–> currency leaves the bank [- Assets (reserves)] 3: interest paid on the loan: currency flows to the bank [+ Assets (reserves)] –>profit registered for owners [+ Liabilities (equity)] 4: principal returns [- Assets (loan “write-off”)]–>currency returns to the bank [+ Assets (reserves)] This is a simple example involving all of the recorded credit money leaving the bank (so all of the currency corresponding to the loan/deposit figures needs to be employed). But a similar procedure can be described for the extreme counter example (all recorded credit money stays in the bank, so no need for currency transfers). In my opinion, this is the only explanation that makes sense. Registering the returned principal as a net asset would violate accounting rules since it would register twice on the asset side (as currency and as “write-off loan money”), resulting in the need for recording a third monetary occurrence (crediting equity out of the blue) with no corresponding double-entry registration. Or else the books will not stay balanced.

Thanks for the explanation, Max. You’ve given me something I can follow up on directly.

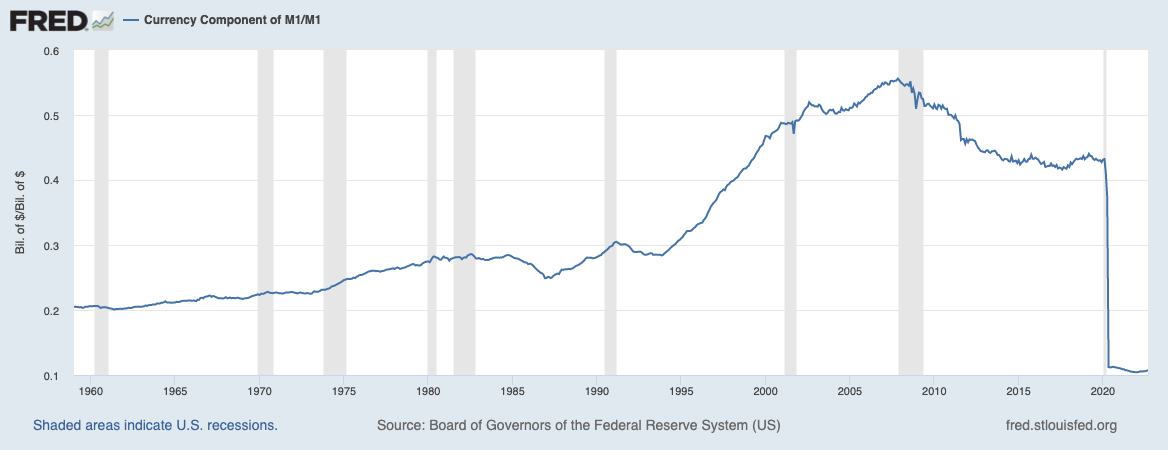

When I refer to money, I’m referring to M1 and M2 monetary aggregates. M1 includes the currency components (FRED series CURRSL). As you can see from Table H.6, currency is about 10% of M1 these days, but that is due to a recent change in the definition of M1 to include savings accounts. Historically, currency was 20-30% of M1 until 2000, when it jumped to 40-50%.

Loan proceeds need not be converted into currency, and most times they are not. Interbank transfers, whether accomplished via physical check or electronic transfer, do not require an exchange of currency, just the exchange of liabilities (deposits).

Bank reserves are not considered part of M1 or M2 and so are not considered money, although they are considered part of the monetary base (see Table H.6). It is my understanding that reserves do not circulate. Maybe currency and reserves are distinct things?

Are you aware of an accounting rule for determining whether a “monetary event” has occurred? I ask this because, as late as 2015, economists like Richard Werner were conducting experiments to empirically test how money is created, and he concluded the “dominant” theory of loanable funds was incorrect and the fringe credit-theory of money was correct. How could the loanable funds theory even be considered viable if the accounting rules were clear on how to treat payments of principal?

The problem is that the balance sheet reflects its current state, not its history. It should be possible to construct balance sheets of a non-bank firm and a bank that are identical at the time the loan is made. For example, imagine the non-bank firm is a store or a brokerage firm that maintains accounts for its customers on its books, which allow it to track store credits, etc.

Using the notation Assets-Liabilities-Equity, at time T0, the nonbank firm’s balance sheet is 100-0-100, and the bank’s balance sheet is 0-0-0. At time T1, both extend a loan, resulting in identical balance sheets of 100-100-0 (the non-bank debits $100 from its assets, credits that $100 to its customer’s account, and credits as a firm asset the customer’s IOU for $100; the bank just credits $100 to both assets and liabilities). At time T2, the debtors repay the loan in full at 10% interest ($10). The non-firm’s balance sheet should be 110-0-110 (I think, if the hypothetical as constructed is logically sound), is the bank’s balance sheet 10-0-10? (NOTE: I don’t think equity is credited; it is calculated by subtracting assets from liabilities).

Thanks for your help in working through this. I appreciate it.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: Clarified non-bank hypothetical

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: added language to distinguish between reserves and currency

-

November 13, 2022 at 1:12 pm #248591

My hypothetical may be wrong. See, this paper from Richard Werner.

-

November 14, 2022 at 4:43 pm #248597

Interbank transfers, whether accomplished via physical check or electronic transfer, do not require an exchange of currency, just the exchange of liabilities (deposits).

Thanks Scot. Are you sure about that? I don’t see how it can make sense from an accounting point of view (deposits can’t just be striked-out by one bank and added to the balance sheet of the second bank). I believe the rest of your exposition (which I think is flawed) is connected to the above point, so maybe it would be helpful to sort it out first.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 3 months ago by max gr.

-

November 13, 2022 at 7:31 pm #248593

Forgive me if I make a point that someone has already made above. I feel the answer is obvious. Loans and deposits move in tandem because an accounting identity is in operation under double-entry bookkeeping and national accounting. Every loan creates a deposit. Assume a bank loans entity A $100,000 for a renovation. This creates a negative entry on the bank’s balance sheet, it’s loan sheet. It also creates a positive entry, a balance, of $100,000 in entity A’s account. As the renovation proceeds, A makes progress payments to B, the contractor. Now, the balance moves to B’s account. The bank still holds the loan as a negative entry (until A pays it off).

If the bank holds too many negative entries, according to banking rules, it can borrow from other banks or from the government. In this case positive and negative entries swap between these entities. Loans and deposits continue to move in tandem. There’s nothing profound or mysterious in these numéraire operations simpliciter (as mere formal quantities, not real quantities) but they have profound effects as rituals of capital creordering the socioeconomy (as per CasP theory). What might be interesting, in the accounting sense, are the “frictional” or “lag” effects shown by the discrepancies. Even this is a weak “might”, IMHO. But please, shoot me down with facts and logic if I am wrong.

Of course, this is not the main original question (money creation as redistribution) which was and is a good question. Again, I think the answer is simple. If rich people and corporations can get get loans at cheaper rates than poor people and small businesses (and they can) then money creation in that milieu or regime does result in redistribution from poor to rich. It looks patently obvious to me, as a crusty old curmudgeon getting more and more exasperated with the idiocies and childish mystifications of planet-destroying capitalism. But again, shoot me down with facts and logic if I am wrong.

-

November 15, 2022 at 4:39 pm #248602

I really don’t think any complex analysis is needed. MMT and CasP have demystified the operations for us.

1. Loans and deposits move in tandem because an accounting identity is in operation under double-entry bookkeeping and national accounting. (MMT)

2. Rich people and corporations get loans at cheaper rates than poor people and small businesses. Money creation in this form must result in redistribution from poor and middle to rich (on a sliding differential scale). (MMT and CasP)

3. Money creation is a power operation in the sense CasP uses the term “power”. (CasP)

4. Money creation is rigged and gamed by the people with power in the system. (CasP)

5. The previous deflation and the zero interest rates were rigged and administered. The current inflation is rigged and administered. (Follows from CasP IMHO.)

6. Why does the rigging of the system change? When the power players determine they have “mined out” a process for all it’s worth (low or zero interest rates) then they will switch the system to the opposite regime (inflation) for further differential gains. Zero percent interest rates permitted big players, those who play in billions, to borrow billions at zero percent interest. That is free money, provided bonds (government bonds perhaps?) can be obtained somewhere with risk-free positive interest rates. However, this process, which delivers differential profits, will sooner or later drive inflation. First it drives asset inflation. Later is may well drive consumer goods and services inflation if and when any of the sloshing money gets to workers at any level, including skilled workers and professionals.

Then, a relatively rapid switch to inflation becomes the new way that big players can reap the differential profits. The asset inflation was useful early as it busted small players (relatively) as they could not purchase assets much at all and their relative wealth declined as those who acquired assets got further large gains. Once the assets are “all acquired” by the big players (e.g. landlords now own most of the housing stock) then the asset inflation game is played out. It is now time for the consumer goods and services inflation game to take all the money workers are now not putting into assets beyond their reach. Interest rates are jacked up and inflationary price rises are administered by monopolies and oligopolies.

Note that central banks are run by boards of appointed business people. Central banks are not run by governments (as they once were in some cases). Equally, central banks are not run by workers. To reiterate, they are run by business stooges. The idea that they would run interest rate policy to do anything for workers or the poor is preposterous. Governments are run by big business too. Donations capture regulation and policy so government fiscal policy also has the fingerprints of big business all over it.

The whole system is rigged by and for the rich. QED. It’s an open and shut case. As I say, there is no mystery now MMT (revived Chartalism) and more importantly CasP have demystified things.

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.