Home › Forum › Political Economy › Privatising Sovereignty – David Ciepely

- This topic has 11 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated February 2, 2022 at 5:22 pm by Scot Griffin.

-

CreatorTopic

-

January 29, 2022 at 4:46 pm #247671

I came across David’s article ‘Privatising Sovereignty’ which was shared to the casp blog by Cory Doctorow and wanted to check my understanding of it with other readers.

David’s thesis is that shareholders are not in fact owners of the company because stockholders:

1. “cannot pull assets out of the corporation”

Yet, if a public company decides via a shareholder vote to liquidate the assets of the company, the proceeds of the sales are allocated based on the percentage ownership determined by relative shareholdings (net debt). When a shareholder decides they want to decrease or divest from their ownership of a company, they sell are selling ‘their portion of the company’s assets’ to another willing buyer in the stock market.

2. “cannot use the assets, exclude others from them, lend them out, borrow on them, sell them, and they have no legal claim to the proceeds from the sale of assets or to company profits.”

They can do so by enabling the CEO to do so and have a claim to the proceeds from sales of assets and other profits via dividends. You might argue (as David does: “this residual profit is then allocated at the discretion of management”) that a company is not obligated to pay out dividends to its shareholders yet this is usually only acceptable to shareholders if they agree to forego their share of the profits in favour of making an investment that would provide them with greater profits in the long-term. Otherwise, shareholders will usually not tolerate companies holding on to any significant reserves of cash that aren’t paid out as dividends. While stockholders have no legal rights to demand dividends, they have means available to them to ensure that they receive them.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

January 29, 2022 at 7:07 pm #247679

David is correct. Here is a link to his essay.

The American Legal Realist movement of the early 20th century recognized that what most of us think of as “property” is actually a bundle of rights (e.g., the right to enjoy, the right to exclude, the right to alienate, the right to control, etc.) Interestingly, not all things that are legally considered property convey every one of the bundle of rights.

For example, the law considers patents to be property, but a patent only gives its owner the right to exclude others from making, using or selling the patented invention. The owner has no right to make the invention himself, if somebody else owns a patent patent covering a sub-system or component of the patented invention.

A share of common stock gives its owner no property rights in the underlying corporation whatsoever. It provides certain contractual rights (a different bundle of rights than provided by property), including the right to receive pro rata distributions of dividends, the right to pro rata distribution of residual value upon dissolution, and the right to vote in the annual shareholder meeting (and any special meetings that might be called), but that’s pretty much it.

Yes, a large enough block of shareholders can exert a great deal of influence on a management team, but that typically results in a negotiation between that block of shareholders and the management team, and activist shareholders are relatively rare (and tracked under SEC rules; the management team knows well ahead of time if they have activist shareholders).

Most companies no longer pay dividends. This has been the case since 1960s, after Miller and Modigliani successfully argued that the overall value of the company is not affected by the payment of dividends (see, Dividend Policy, Growth and the Valuation of Shares, 1961). Indeed, paying a dividend typically reduces the share price by the amount of the dividend (at least temporarily). Four of the ten U.S. largest companies (by market cap), including Amazon, Google (Alphabet), Facebook (Meta Platforms) and Tesla have never paid a dividend, and they are all sitting on piles of cash.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: Added link to referenced article

-

January 29, 2022 at 9:28 pm #247686

Most companies no longer pay dividends.

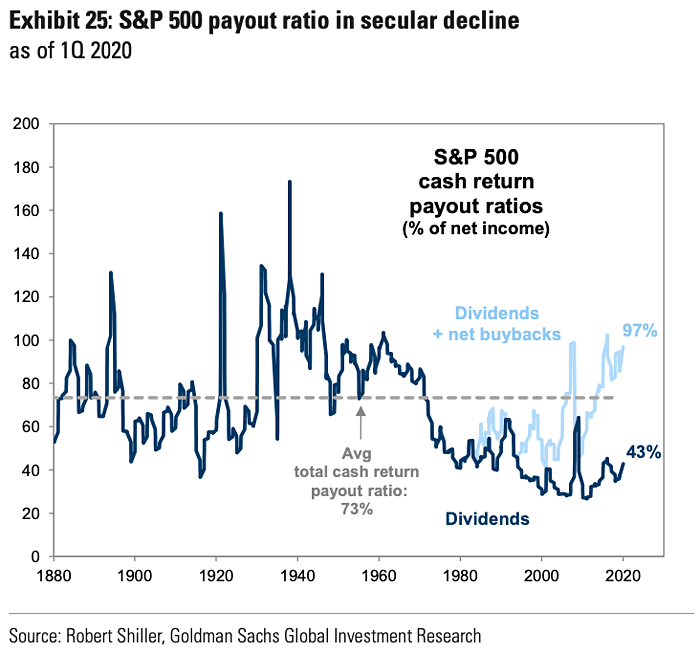

The data below are only marginally germane to the broader argument, but they are interesting nonetheless.

This chart is from Blair Fix: https://capitalaspower.com/2015/07/some-important-limitations-of-income-inequality-data/

Here is the U.S. dividend payout ratio. It has risen significantly since the 1980s, and at times it even exceeds 1!

-

January 29, 2022 at 8:25 pm #247682

Debate on the separation of ownership from control started in the 1930s with Berle and Means’ book on The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and it continues for two obvious reasons.

First, corporations are legally bounded, which means that even sole owners cannot do whatever they like with them. Second, the principal/agent structure of corporations inserts a layer of separation that further limits the flexibility of their formal owners, particularly if they don’t have a majority stake.

But this debate often misses the point, namely, that the overarching subject here is not the owners/executives/policymakers, but Capital itself.

In the final analysis, capitalism is not governed by individual capitalists, even though it often seems that way. It is not the Rockefellers, Carnegies, Morgans, Soroses, Zuckerbers and Musks of the world that run the show. And it is not even the corporations that they own that stir capitalism. Instead, it is the inner logic of capital that subjugates them all.

So why does CasP put so much emphasis on corporations — particularly the large ones — and on the dominant capitalists and executives that own and manage them?

The answer is that, according to CasP, the inner logic of capitalism is about differential power, and the imperative of differential power drives and creates taller and taller hierarchical structures headed by state-supported large corporations, their top executives and key owners.

By analyzing the various processes of sabotage that leading corporations/government officials/owners/executives engage in and the resistance they face on the one hand, and by contrasting these processes with their differential income, risk and assets on the other, we can draw meanigful conclusions on the changing nature of capital as power.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

January 29, 2022 at 9:17 pm #247685

Debate on the separation of ownership from control started in the 1930s with Berle and Means’ book on The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and it continues for two obvious reasons. First, corporations are legally bounded, which means that even sole owners cannot do whatever they like with them. Second, the principal/agent structure of corporations inserts a layer of separation that further limits the flexibility of their formal owners, particularly if they don’t have a majority stake. But this debate often misses the point, namely, that the overarching subject here is not the owners/executives/policymakers, but Capital itself.

Debate on the separation of ownership from control started in the 1930s with Berle and Means’ book on The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and it continues for two obvious reasons. First, corporations are legally bounded, which means that even sole owners cannot do whatever they like with them. Second, the principal/agent structure of corporations inserts a layer of separation that further limits the flexibility of their formal owners, particularly if they don’t have a majority stake. But this debate often misses the point, namely, that the overarching subject here is not the owners/executives/policymakers, but Capital itself.Still, asking the question of what do you really own when you own a financial asset is of extreme interest, even beyond the question of ownership and control of a corporation. Understanding the legal underpinnings of capital ought to help better understand the logic of capitalism itself.

In the final analysis, capitalism is not governed by individual capitalists, even though it often seems that way. It is not the Rockefellers, Carnegies, Morgans, Soroses, Zuckerbers and Musks of the world that run the show. And it is not even the corporations that they own that stir capitalism. Instead, it is the inner logic of capital that subjugates them all.

The gravitational pull of the logic of capitalism seems to grow stronger the closer you get to dominant capital. I don’t know if that is a phenomenon anyone has explored with CasP. Clearly, everyone is subject to the Market and, therefore, subjugated by the inner logic capital to some extent. But there are plenty of low-grade capitalists (individuals and firms) for whom differential accumulation (as compared to other capitalists) is neither a goal nor a concern, for example.

But once you find yourself in the orbit of dominant capital, which every publicly-traded company necessarily is, hoo-boy. Private equity firms and certain private conglomerates like Khoch Industries are the inner logic of capitalism personified.

the imperative of differential power drives and creates taller and taller hierarchical structures headed by state-supported large corporations, their top executives and key owners.

Is this always the case? One of the reasons I believe Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have such large market caps is because they’ve managed to capitalize the future earnings of those outside of their corporate hierarchies. Amazon, for example, makes a good amount of money through tribute paid by firms that will never reach the scale required to go public who want to expand their reach using the Amazon platform. The platforms of each of these companies allow them to “enclose” other corporations without purchasing them or giving them a seat at the dominant capital table. They are fractally replicating the market itself.

-

January 29, 2022 at 9:59 pm #247687

But there are plenty of low-grade capitalists (individuals and firms) for whom differential accumulation (as compared to other capitalists) is neither a goal nor a concern, for example.

I’m not sure. I think all capitalists are gripped by benchmarks — the main difference is that most small capitalists are obsessed with meeting the average, whereas larger ones try to and sometimes can beat it.

Is this always the case? One of the reasons I believe Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have such large market caps is because they’ve managed to capitalize the future earnings of those outside of their corporate hierarchies.

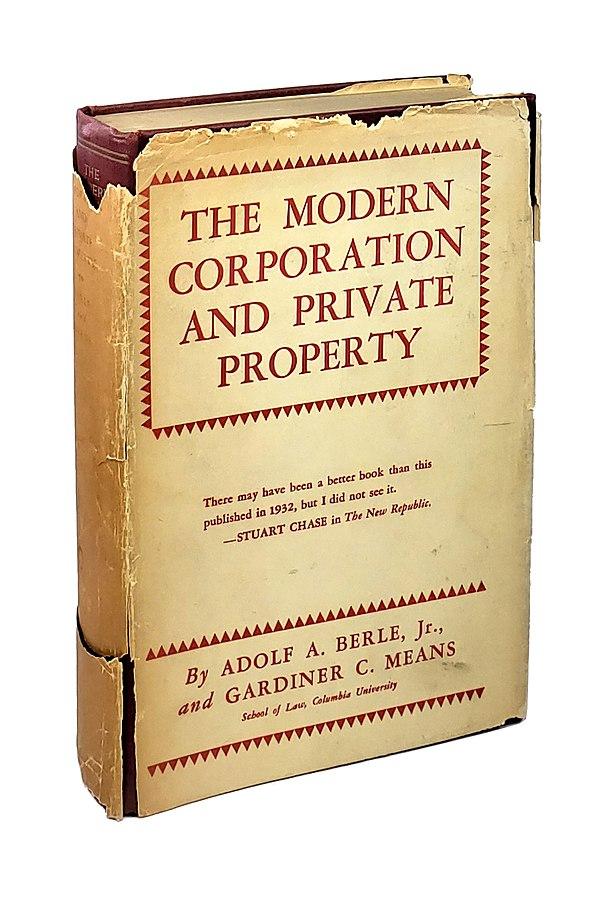

The inner hierarchies of the corporations themselves are only one aspect of hierarchical power, and not necessarily the most important one. In Section 3.3 of ‘Growing through Sabotage’ (2020), we classified corporations as micro hierarchies, nested in meso-hierarchies and further in meta-hierarchies. If we consider the full spectrum of social hierarchy, we might find that today’s capitalism is the most hierarchical society ever.

-

-

January 29, 2022 at 10:44 pm #247688

The inner hierarchies of the corporations themselves are only one aspect of hierarchical power, and not necessarily the most important one. In Section 3.3 of ‘Growing through Sabotage’ (2020), we classified corporations as micro hierarchies, nested in meso-hierarchies and further in meta-hierarchies. If we consider the full spectrum of social hierarchy, we might find that today’s capitalism is the most hierarchical society ever.

This is a good way of thinking about things, actually. Thanks.

-

January 29, 2022 at 10:59 pm #247689

Here is the U.S. dividend payout ratio. It has risen significantly since the 1980s, and at times it even exceeds 1!

The ratio exceeds one because many corporations aren’t profitable. Ironically, the only companies I know who pay dividends even when they lose money are the big oil companies like Exxon Mobil.

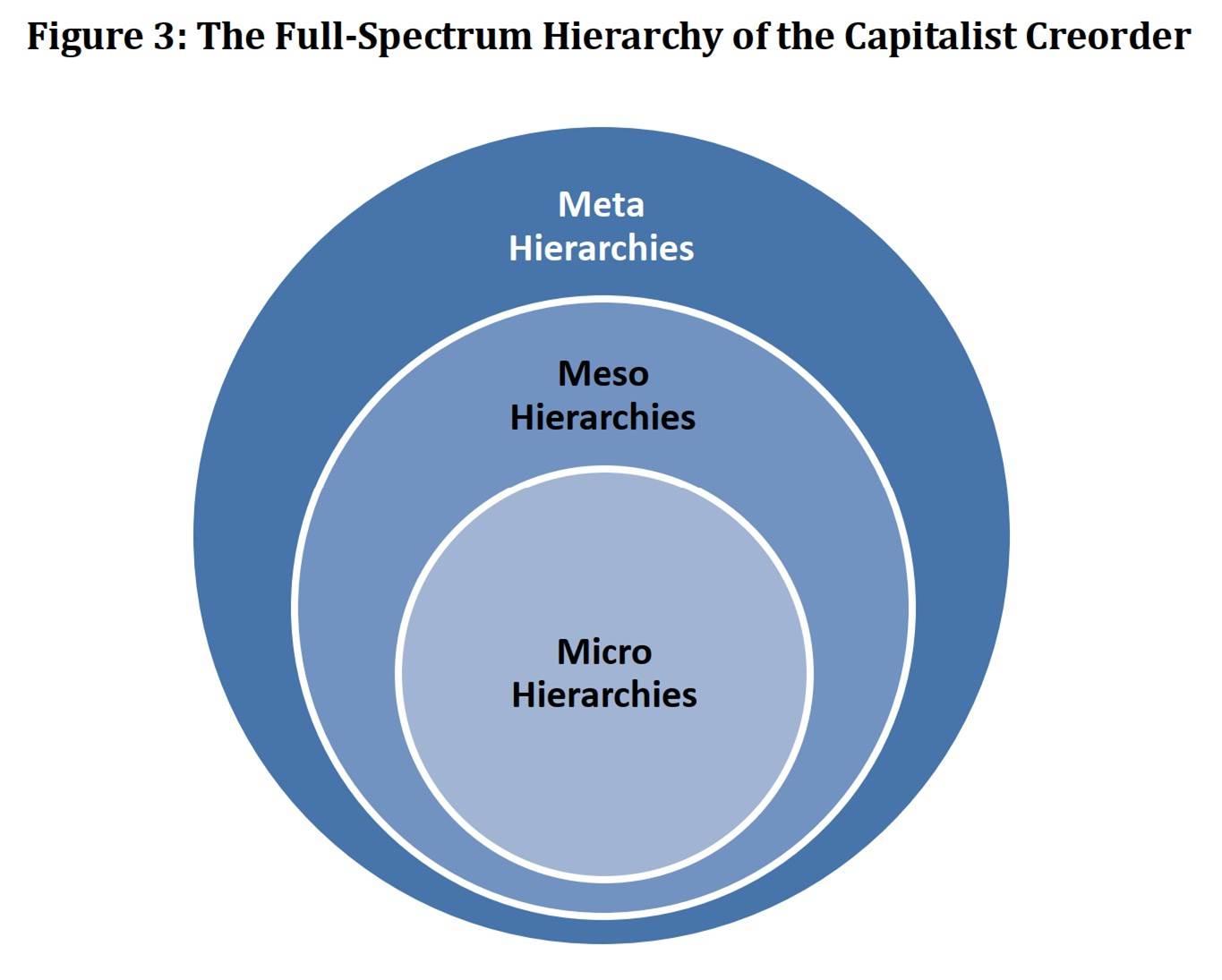

A paper of interest is Fama, Eugene F. and French, Kenneth R., Disappearing Dividends: Changing Firm Characteristics or Lower Propensity to Pay? (June 2000). Available at SSRN or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.203092

Here’s the “money” chart from the paper:

Miller and Modigliani’s work, along with CAPM and the Rational Market Hypothesis, form the bedrock of Modern Finance that currently drives the inner logic of capitalism. Their two key papers were published in June 1958 and October 1961 (the dividend paper).

Justin Fox’s The Myth of the Rational Market is a very readable account of the rise of Modern Finance.

-

January 30, 2022 at 9:59 am #247691

The ratio exceeds one because many corporations aren’t profitable.

Since the 1980s, the share of net profit in national income has trended upward, and a growing share of these profits has gone to dividends. Currently, dominant capital pays over 40% of its net profit in dividends (and another half in buybacks). It is true that a smaller number of firms pay dividends, but those who do seem to compensate for the shortfall.

-

-

February 2, 2022 at 1:41 pm #247700

Seems like the data is fuzzy with regard to the prevalance of dividend payments. If we assumed that corporations do redistribute their profits as dividends, would that be enough to cast doubt on Ciepely’s thesis? What other rights/beneifts do shareholders not receive which prevent them from being considered owners?

The American Legal Realist movement of the early 20th century recognized that what most of us think of as “property” is actually a bundle of rights (e.g., the right to enjoy, the right to exclude, the right to alienate, the right to control, etc.)

More specifically, I’m wondering how you would envision shareholders enjoying the full bundle of rights you listed above. Board approval is (theoretically) required before stocks can be issued and if board members represent shareholders, then this gives shareholders a de facto right to exclude others from ownership. Shareholders can sell their shares and therefore have the right to alienate and by using votes, have the right to control the company’s assets.

It seems to me that the bottom line is that between them, shareholders and managers enjoy the full bundle of rights to a company and i’d argue that shareholders still enjoy the lion’s share of those rights even though many may choose to not exercise their rights due to disinterest or trust in the managers appointed

edit: sorry, haven’t quite gotten the hang of the quote mechanism

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by rk374.

-

February 2, 2022 at 5:05 pm #247706

Seems like the data is fuzzy with regard to the prevalance of dividend payments. If we assumed that corporations do redistribute their profits as dividends, would that be enough to cast doubt on Ciepely’s thesis?

No. If corporations distributed all of their un-invested profits as dividends, that would simulate actual ownership, but issuing dividends is a discretionary act of the board of directors and management.

What other rights/benefits do shareholders not receive which prevent them from being considered owners?

Shareholders can sell their shares and therefore have the right to alienate and by using votes, have the right to control the company’s assets. It seems to me that the bottom line is that between them, shareholders and managers enjoy the full bundle of rights to a company and i’d argue that shareholders still enjoy the lion’s share of those rights even though many may choose to not exercise their rights due to disinterest or trust in the managers appointed

Shareholders lack the control necessary to be considered owners of the corporation itself. Simply put, they do not control, nor do they have the right to control, the corporation, its managers or its assets, by vote or otherwise. That’s the job of the board of directors.

Shareholders are allowed to vote at the annual shareholder meeting, but the board generally determines what items/issues are up for a vote. Shareholders can place their own proposals to be added to the proxy and put up for shareholder vote, if they do so within the time and manner specified by law. Of course, the board controls the printing and presentation of the proxy and is free to oppose any shareholder proposals. (By the way, shareholder proposals are rare, but see the latest Apple proxy statement.)

The most aggressive shareholder proposals involve trying to replace current board members with their own candidates. This is called a proxy fight. Typically, though, corporations have staggered boards or have other mechanisms in place to ensure that only a minority of board seats are open any given year, e.g., a 9-member board will only have 3 seats open each year. So, even if you as a shareholder get your members elected to the board, they’re still in the minority. Boards typically act unanimously (you never see a dissenting vote in board minutes) and won’t put anything up for a vote that has not been informally agreed. Thus, minority board members have a kind of veto power that potentially allows them gum up the works, but it is in their interest to go along on most things. For their hot-button issues, they need to convince the other board members to vote with them.

Large shareholders do have a voice and many of them seek and receive access to top management, often on a quarterly basis after an earnings call. Shareholders in growth companies don’t want or expect dividends because they want the money to be invested in creating earnings growth. If growth slows and a company is sitting on a lot of cash, I am sure large shareholders will ask about dividends (I’ve heard them ask for share buybacks, for example).

Board approval is (theoretically) required before stocks can be issued and if board members represent shareholders, then this gives shareholders a de facto right to exclude others from ownership.

Publicly traded companies rarely issue new stock after their initial public offering, except as part of employee compensation as stock options and restricted shares. Thus, virtually all of the shares traded on a stock exchange every day are already existing shares.

The only way the board of a publicly traded company could prevent shares from being traded on a stock exchange is by voluntarily delisting the company, which is rarely done (and typically only if the board believes the company is undervalued). The whole point of taking a company public is to allow current shareholders to sell their shares to new shareholders. By delisting the company, you get rid of all liquidity for the stock, effectively reducing its value substantially (because there is no longer an objective market value for the shares).

-

February 2, 2022 at 5:22 pm #247707

One thing to keep in mind is that CasP seeks to understand and explain the behavior of dominant capital, not the behavior of individual capitalists/investors. There are similarities, e.g., the drive for differential accumulation, but they are not the same.

-

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.