- This topic has 8 replies, 7 voices, and was last updated November 6, 2022 at 5:57 pm by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

CreatorTopic

-

November 1, 2022 at 3:26 pm #248510

by Shimshon Bichler & Jonathan Nitzan

Marxists love to hate the theory of capital as power, or CasP for short. And they have two good reasons. First, CasP criticizes the logical and empirical validity of the labour theory of value on which Marxism rests. And second, it offers the young at heart a radical, non-Marxist alternative with which to research, understand and contest capitalism. With these reasons in mind, it is only understandable that most Marxists prefer to keep Pandora’s box closed, and few challenge CasP directly.

Sometimes, though, the wall of silence breaks, typically by a lone Marxist who lashes at the ‘idealist’ renegades of forward-looking capitalized power and reiterates the good old ‘material reality’ of backward-looking labour time. Since these occasional critics are often confident in their dogma and rarely bother to understand the CasP research they criticize (let alone the broader body of CasP literature), their critiques scarcely merit a response. But occasionally, they accuse us of empirical wrongdoing – and these charges do call for a reply.

Such accusations are levelled in a recent paper by Nicolas D. Villarreal (2022), titled ‘Capital, Capitalization, and Capitalists: A Critique of Capital as Power Theory’. In his article, Villarreal claims that our empirical analysis of the relation between business power and industrial sabotage in the United States is unpersuasive, to put it politely (Nitzan and Bichler 2009: 236-239). He argues that we cherry-pick specific data definitions and smoothing windows to ‘achieve the desired results’; that these ‘results are driven by statistical aberrations’; and that his own choice of variables pretty much invalidates our conclusions.

Unfortunately, Mr. Villarreal’s empirical counter-analysis leaves much to be desired. His ‘reproduction/refutation’ of our work is not only poorly documented, but also uses incorrect variables, including ones that differ from those labelled in his own figures (gross instead of net income, domestic instead of national variables, national categories mixed with domestic ones, etc.). So instead of trying to reverse-engineer his results, here is our own easy-to-follow, step-by-step reply to his complaints. Hopefully, this reply will make future critics a bit more careful with their dismissive arguments. [continue reading]

***

The two papers, complete with figures and data:

Villarreal, Nicolas D. 2022. Capital, Capitalization, and Capitalists. A Critique of Capital as Power Theory. Pre-History of an Encounter, October 25. https://nicolasdvillarreal.substack.com/p/capital-capitalization-and-capitalists

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2022. The Business of Strategic Sabotage. Working Papers on Capital as Power (2022/02, October): 1-11. https://bnarchives.yorku.ca/750/

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

November 2, 2022 at 6:14 pm #248522

An initial thought on this debate. Bichler and Nitzan are characterised by Nicolas D Villarreal as:

“Declaring that both neoclassical and Marxian political economy have been done in by their subscription to the idea that there is a real economy which regulates the nominal/financial economy, and that this real economy can be quantified, with utils and demand curves in the case of neoclassical econ, and socially necessary labor time in the case of Marxian econ. The CasP theorists suggest that these measures of the real economy are in fact unquantifiable, and that, in fact, there is no underlying real economy, that it is finance and finance alone which structures our social reality.” – Villarreal.

This is a misunderstanding and mischaracterisation by Villarreal of what B&N are saying. They are NOT saying there is no underlying real economy. They are NOT saying that the real physical processes and results of the real physical economy do not occur. They are saying the financial economy is not an accurate reflection or mirror of the real economy. They are saying that the real economy cannot be quantified and accurately reflected, in finance capital operations, by utils or SNALTs or their proxy measure, the numeraire, as money capital.

B&N are not saying it is finance and finance alone which structure our social reality. They refer to the real human acts of cooperation and production in industrious work. This is plain. What they do say is that finance (finance capital) is not a measuring set but an instruction set. More precisely it does not measure value, it deems value and issues instructions (capital investment) on that basis. It does not measure or reflect what is really happening. It takes a false aggregated measure in a fictitious unit, deems it to be a real measure and issues instructions for production or no production on that basis alone and does so (under capitalism) to maximize profit. It attempts this by keeping strategic sabotage of production in the “Goldilocks Zone” (for profits on capital, not for the good of the majority of the people).

-

November 3, 2022 at 11:03 am #248525

On page 2 of this article, you write that “Business per se – namely, purchases, sales and manipulation for the sake of redistribution and differential accumulation – is external to industry proper and therefore has nothing to contribute to it. Its only connection to industry is negative, via ‘sabotage’.”

Industry has indeed to be sabotaged when society heads too far to the right side of Figure 1. But wouldn’t business have to propel industry when we move too far left?

This last hypothesis is also commonsensical: what are advertisements, fashion, sales representatives, etc. for if not to forge new needs and stimulate consumption, hence industry?

In that sense, business would not only be a negative force but a productive one as well.

@Jonathan, could you clarify this point?

-

November 3, 2022 at 10:12 pm #248526

(1) Let’s tell a simple parable. In this parable there are two separate groups of 100 people each, called ‘industry’ and ‘business’.

(2) Industry is characterized by two features: (1) its members deliberate/cooperate/act autonomously and democratically to determine both their goals and the most effective ways and means of achieving those goals; and (2) their goals concern not only their output, but also — if not more so — the very processes of producing this output and developing themselves and the institutions that participate in this production.

(3) The purpose of the business group is to control industry and use this control to extract income from it. The effect of business on industry can be positive, nil or negative. However, if the impact is positive, and if industry endorses and applies it, then business is no longer separate from industry, but part and parcel of it. And since business becomes part of industry and no longer controls it, it cannot extract any income from it. By contrast, if the effect of business on industry is nil or negative, industry — assuming it is autonomous – is likely to reject it. In this case, the only way for business to have the last say, is by enforcing this impact – i.e., by ‘sabotaging’ industry.

(4) If we accept this parable as a way of thinking about actual capitalism, it follows that the industry-business distinction holds only when business sabotages industry. And this condition means that the only thing that business can do is calibrate the nature and intensity of industrial activity by setting sabotage somewhere between none (full industrial capacity shown the rightmost point on Figure 1) and total (zero industrial capacity shown by the leftmost point in Figure 1). According to our parable, though, this calibration contributes nothing to industry; it merely allows it greater or lesser freedom to act in the best the interest of humanity.

(5) And now to your question, Corentin:

[W]hat are advertisements, fashion, sales representatives, etc. for if not to forge new needs and stimulate consumption, hence industry?

Our answer: advertisement, fashion, sales representatives, etc. contribute not to industry, but to the business control of industry. An autonomous society decides for itself, democratically, what to do and how. It has no need for business stimulation, advertisement and the creation of ‘new needs’. If we are ever to see such society emerging, it will likely move away from the sabotage that business relentlessly imposes and glorifies (private transportation, urban sprawl, fast food, conspicuous consumption, brainwashing, poisonous production, etc.), as well as scale back the enormous waste of sustaining and fortifying the power hierarchies that business uses to control us all.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

November 4, 2022 at 8:32 pm #248532

By Tia & Max

Increased consumption and the inception of ‘new needs’ does not equate with wellbeing. And it does not imply that business is productive. But Corentin raises an issue which we know to bother some of us who try to think in the above terms.

In actuality, industry is not a separate, autonomous and deliberate institution. It has no democratic organizational structure of its own, but one that is intertwined with business management. Industry’s autonomy might well be a potentiality (with strong grasp in reality, since without this potentiality being manifested at least partially, social production could not exist), but under capitalism its ‘terrain’, so to speak, is already everywhere dismorphed and dislodged. Its cooperative DNA is already ‘infected’ by business control, which does not exert itself from the outside but channels industry from the inside.

Industry is not only intertwined with business at present, the two also emerged together. industry as the rationalization of cooperative processes of creation and production appeared alongside the fundamental institutions of capital, and so we do not even have a concrete historical example of industry operating without the effects of business upon it.

Assuming this is a valid description, a question arises concerning appropriate proxies for sabotage. If the proxy is unemployment, does it follow that when employment rises industry is necessarily less sabotaged? Even if the added employment is directed at the production and consumption of junk? Surely, full employment does not mean in this case a fully autonomous and wellbeing-oriented industry.

We can think of unemployment as a wide measure of sabotage, but only if we consider it as one dimension of the latter: as sabotaging the given industrial terrain, which is already shaped by needs, production Techniques and goals co-determined by business power. And if this is the case, we might have a complication because we are talking about different levels of analysis. The ‘upper’ level of sabotage might indicate a falling share of capital income as unemployment diminishes, but this does not necessarily mean industry operates in a more autonomous, democratic and deliberate mode. It can mean something else entirely: workers manage to wrestle a higher share of income while producing and consuming more junk, destroying the environment and poisoning the entire population (expressions of ‘deeper’ societal sabotage).

This line of reasoning alludes to the possibility that different metrics of sabotage, referring to different levels of analysis, might move in opposite directions. More importantly, it is not clear why a single viewpoint, that of capital and the distribution of income, should be able to give us a clear-cut ‘bottom-line’ when estimating the ‘degree’ of industry’s autonomy (which is not the same as estimating power relations between different social groups).

P.S.

Castoriadis offers an alternative way with which to understand the dynamic nature of innovation under capitalism, which might be of relevance. He writes: “…what we see is neither technology creating capitalism, nor capitalism creating out of nothing an entire technology to meet its wishes; what we see is the emergence of a capitalist world, of which this technology is an ‘everywhere dense subset'” (Technique, Crossroads in the Labyrinth, 1986: 252). This “technology” is characterized by an abundance and diversity of innovation: “for every ‘need’, for every productive process, it develops not one object or technique, but a vast range of objects and techniques”. Thus, the selection between these creative potentials of production, the promotion of some techniques and the simultaneous repression of others, lies at the heart of the dynamics of power and resistance under capitalism.This means that one dimension in which the analysis of business-industry relations should be carried out is at the level of industrial transitions – how these play out, who do they benefit, and what wider changes do they harbor.

-

November 5, 2022 at 11:06 am #248533

Here is a fun account from a software business consultant of the non-linearity of the relationship between sabotage and profit. He calls the point at which businesses sabotage their product/service so much that people stop using it “the trust thermocline.” Veblen would call it charging more than the traffic will bear. It seems there is a market for CasP analysis in the business world!

full thread: https://twitter.com/garius/status/1588115310124539904

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by CM.

Attachments:

You must be logged in to view attached files. -

November 6, 2022 at 11:32 am #248542

I read Villarreal’s critique of CasP as soon as I saw it. Before I raise issues with his model, I should say that I hope people use this forum for critiques of CasP. Certainly people can use their own blogs or Twitter feed, but the lack of critiques on this forum is not an editorial decision. We either get ignored or we hear that someone is trying to punch us from a distance. As long as one is not shitposting, sceptics of CasP are welcome here.

Villarreal presents his model to corroborate his critique of BN’s model of strategic sabotage:

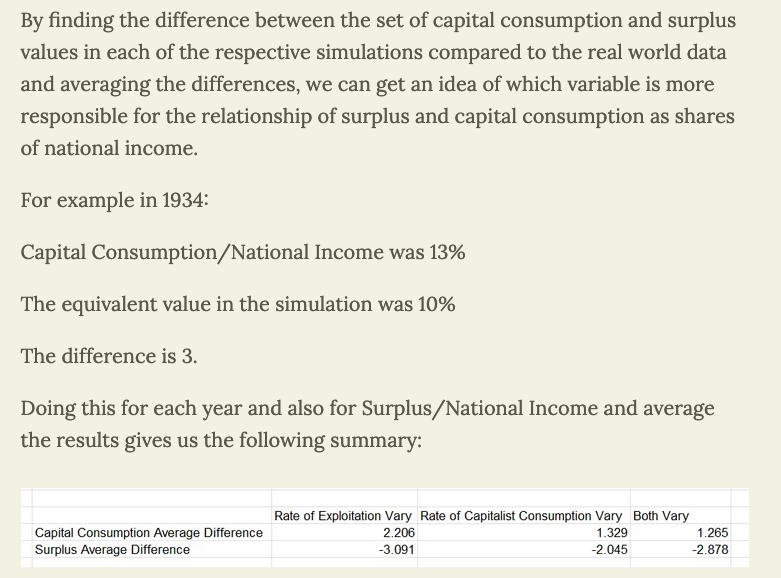

“As you can see, changes in the rate of capitalist consumption (or the rate of capitalist investment) produce outputs in the simulation 30-50% closer to reality than changes in the rate of exploitation. This indicates that capitalist consumption and investment is primarily responsible for driving the relationship between surplus and capital consumption (aka depreciation). It isn’t a pure struggle for power as financial accumulation which is determining profits, especially not through the labor market and strategic sabotage. Instead, it is the decisions regarding physical, real investment which determine profits, and it is this impact over the material world which actual class struggle is concerned with.”After downloading his model output and looking at his R code I want to raise three issues with Villarreal’s model of capital consumption and surplus.

1. I can’t understand how one uses model error, which he gets backwards, as it should be estimate minus actual, not the other way around, to establish the significance of a variable in producing an effect. Predictions are more accurate when error is low, but I am perplexed because you can have low model error on variables that are insignificant to an outcome. All it means is that your model correctly estimated the variable well — we still don’t know how important it is.

2. I looked at Villarreal’s comments on Twitter and he seems to have the drive to scrutinize CasP like a forensic accountant on payday. When he posts about his own model he is much more casual in the assessment of its results. Within the post that critiques CasP, his model will sometimes get an eyeball test. But there are curious qualities that one should put under the microscope.

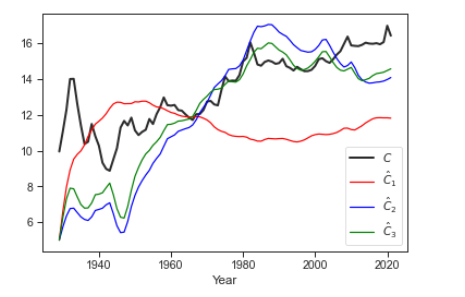

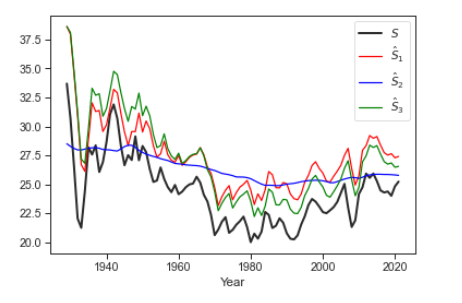

Here are two plots of the actual data from the national accounts and the three versions of his model (labelled 1,2,3 for convenience, but they are in the same order as his Excel sheet).

Notice that it is much wilder at modelling capital consumption than it is at modelling surplus. The two stronger models of capital consumption (2,3) fail around the inflection point of this figure, which he states are two regimes of accumulation. The model that gets post-1980s “right” gets everything else wrong.

What about the seemingly perfect correlations between some of the surplus models and the surplus data? Well …

3. Villarreal is not simply explaining the relationships between columns in national accounts; he is claiming that the various concepts of Marxist economics (organic composition of capital, rate of exploitation) are “behind” ratios and variables we can download on a site like FRED.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume the past and present magnitudes of productive value are measurable as socially necessary abstract labour time, just as long as you have a good method to “see” them (because national accounts are in nominal dollars and cents).

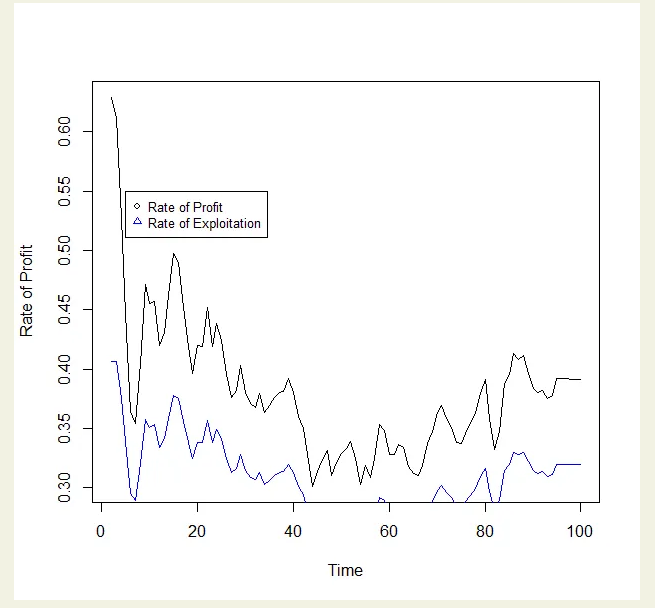

Villarreal’s model first looked odd to me when I saw a figure that he probably thinks is a good sign:

To me, this is an odd figure because, to the naked eye, it looks like an estimated rate of exploitation, which will not unite Marxists because many Marxists in fact have abandoned any hard quantitative version of the LToV, is simple to measure; it’s appearing to be just a constant share of the rate of profit, which we can calculate.

Villarreal will likely respond with a correction: he is deriving the rate of exploitation from the data on the rate of profit, not simply multiplying the latter by some constant (0.65, 1.1, etc.).

But when looking at his code, I am having a hard time untangling a puzzle: what is happening with all the V values? If you follow the R code, it appears that V is derived from external csv file that imports the rate of exploitation. There might be nothing inconsistent with the definitional relationships in Villarreal’s model, but we don’t get a picture of how the model predicts V, well or poorly.

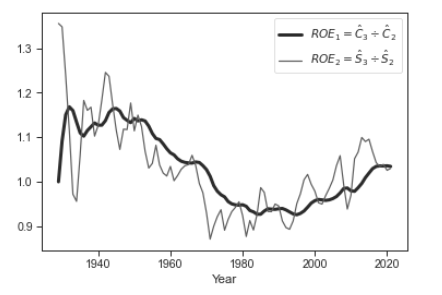

We can estimate the rate of exploitation with a ratio of two versions of the model: Model 3, where everything varies, and Model 2, where rate of exploitation is fixed.

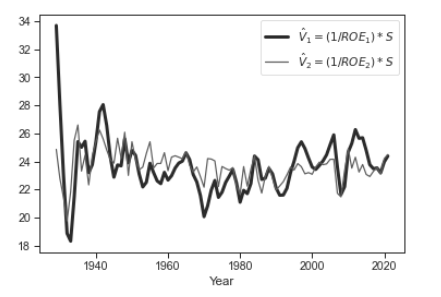

We can the derive an estimate of V with an inversion of the ROE multiplied by S, which would leave V.

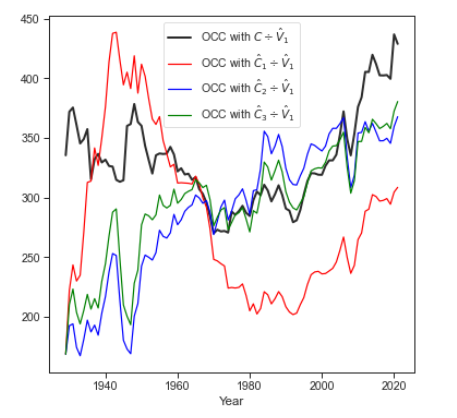

I’m taking all these steps because it is not entirely clear what needs to be fixed or assumed to have the correlation between C and S have a clear Marxist explanation. Here for instance, are measures of the organic composition of capital, assuming the only issue is method (which is not the only issue). Just can Villarreal’s model has issues with predicting the bends and curves of C, the organic composition of capital (C/V) is just as wild.

Overall, I am having a hard time being convinced of the bigger claim, which is not simply that there is a relationship between C and S. For one, the C-S bend in the 1980s produces divisions in what model can explain what. Moreover, the same issues cascade with Marxist ratios like the organic composition of capital.

Coming from a Marxist political economy department, this exercise is reminding me of all the twists and turns that are necessary to show that Marx was right … all along. I have spent a few hours looking at Villarreal’s blog post and code, and my last recommendation is this: comment your code and help your readers see each step at each twist and each turn.

Here is the cleaned csv that I used. Villarreal’s excel sheet has different numbering formats per sheet (percentage / number), so I cleaned that and put it all on one.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by jmc.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by jmc.

Attachments:

You must be logged in to view attached files. -

November 6, 2022 at 2:37 pm #248547

Thanks, James, for digging into the details of Villarreal’s model. I can’t comment on this model specifically, as I haven’t put in the time to understand it. (Thanks for doing that, by the way.)

However, I will comment on models in general. First, when someone publishes a model, you have to expect that the results will be ‘good’, meaning it reproduces what they designed it to reproduce. If the model didn’t do that, the person in question wouldn’t publish their results. So start with the assumption that all published models will have fairly small error.

Now, if you believe Milton Friedman, you should believe these model precisely because the error is small. Never mind the assumptions, he said, they don’t matter. Only ‘predictions’ matter.

Good scientists know this is bullshit. Everything is in the assumptions. So when you see that a model gives ‘good’ results, you have to tear apart its assumptions. If those are bad, then the model is bad.

Also, you need to distinguish between ‘tuning’ and ‘testing’. Models have parameters that we can tune to fit data. That’s fine. But it’s not a test of the model. To test the model, you take these tuned parameters and apply them to another dataset.

Anyway, I agree with your conclusion. Building and explaining models so that other people can understand and use them takes an excruciating amount of work. Which is why I’m not commenting on the details of Villarreal’s model … I’m busy doing modeling of my own!

-

November 6, 2022 at 5:57 pm #248548

What does the harnessing of matter and energy tell us about the history of humanity?

1. Consider the following chart, taken for our paper ‘Growing Through Sabotage’, and assume that the numbers it shows are correct. Do these numbers tell us anything about the social formations of families, tribes, chieftainships and states? About slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism and fascism? About where society is likely to be on the spectrum between direct democracy and tyranny? Energy and matter create an ‘envelope of the possible’: the more energy and matter being converted, the more energy and matter are available for use. But the quantities that end up being used and the purpose for which they are used remain open-ended.

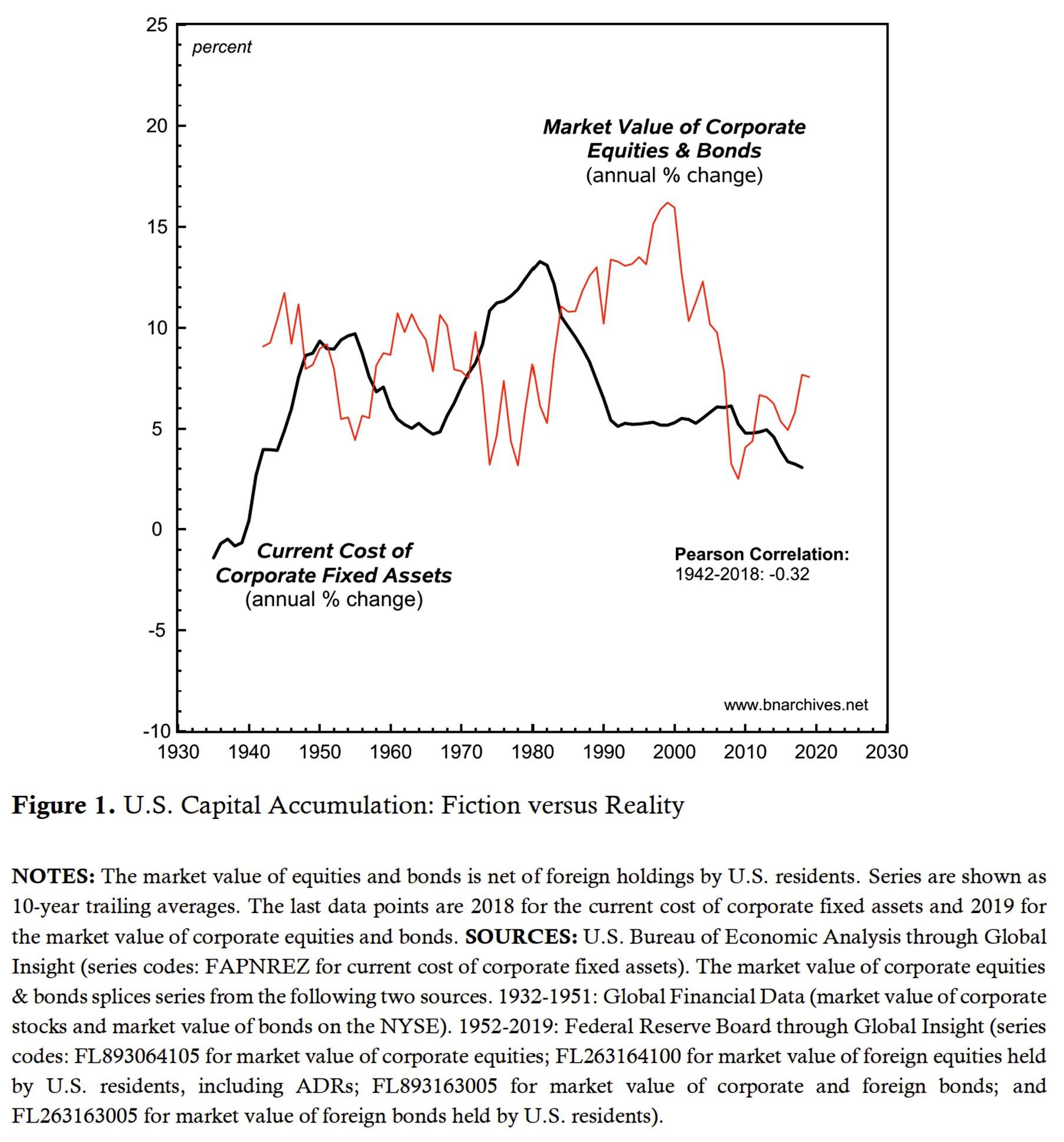

2. In capitalism, the important quantities are not material/energetic, but pecuniary, and pecuniary magnitudes are the product of both quantities and price. This fact means that, with different prices, the same material/energetic quantity can give rise to different pecuniary magnitudes (see the enclosed chart from Blair Fix’s paper, ‘The Truth About Inflation’, showing the range of price changes associated with a given rate of inflation). And since relative prices are a matter of power, so are the pecuniary magnitudes they give rise to.

3. On its own, the fact that capitalism creates more backward-looking ‘capital goods’ counted in terms of energy/matter/labour time tells us little about the forward-looking accumulation of ‘capital’ which discounts risk adjusted expected future earnings (not to speak about their differential magnitudes). The chart below, taken from our rejected interview, ‘The Capital as Power Approach’, shows that, in the United States, the growth of these two magnitudes are inversely correlated. In other words, the two ‘accumulations’ — the one dear to economists and the other that matters to capitalists — are opposite in their direction, and labelling the former ‘real’ and the latter ‘fictitious’ does nothing to make this problem go away.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 4 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.