- This topic has 4 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated December 15, 2022 at 7:35 pm by .

-

Topic

-

Hi everyone,

As emphasised in CasP research, understanding capitalists’ fear allows to better grasp capitalist crises and limits to capitalist power. In that context Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler propose the stimulating concept of systemic fear:

“Under normal circumstances, the performance of this ritual quantifies the way capitalists expect their power to unfold: the earnings they hope to redistribute, the risk they try to minimize and the normal rate of return that secures their rule as natural and their command as eternal. But during times of systemic fear, when the very future of their power is put into question, discounting cannot be properly performed, and the capitalization ritual, which otherwise embodies their confidence in obedience, breaks down” (Bichler & Nitzan, 2010, p. 38)

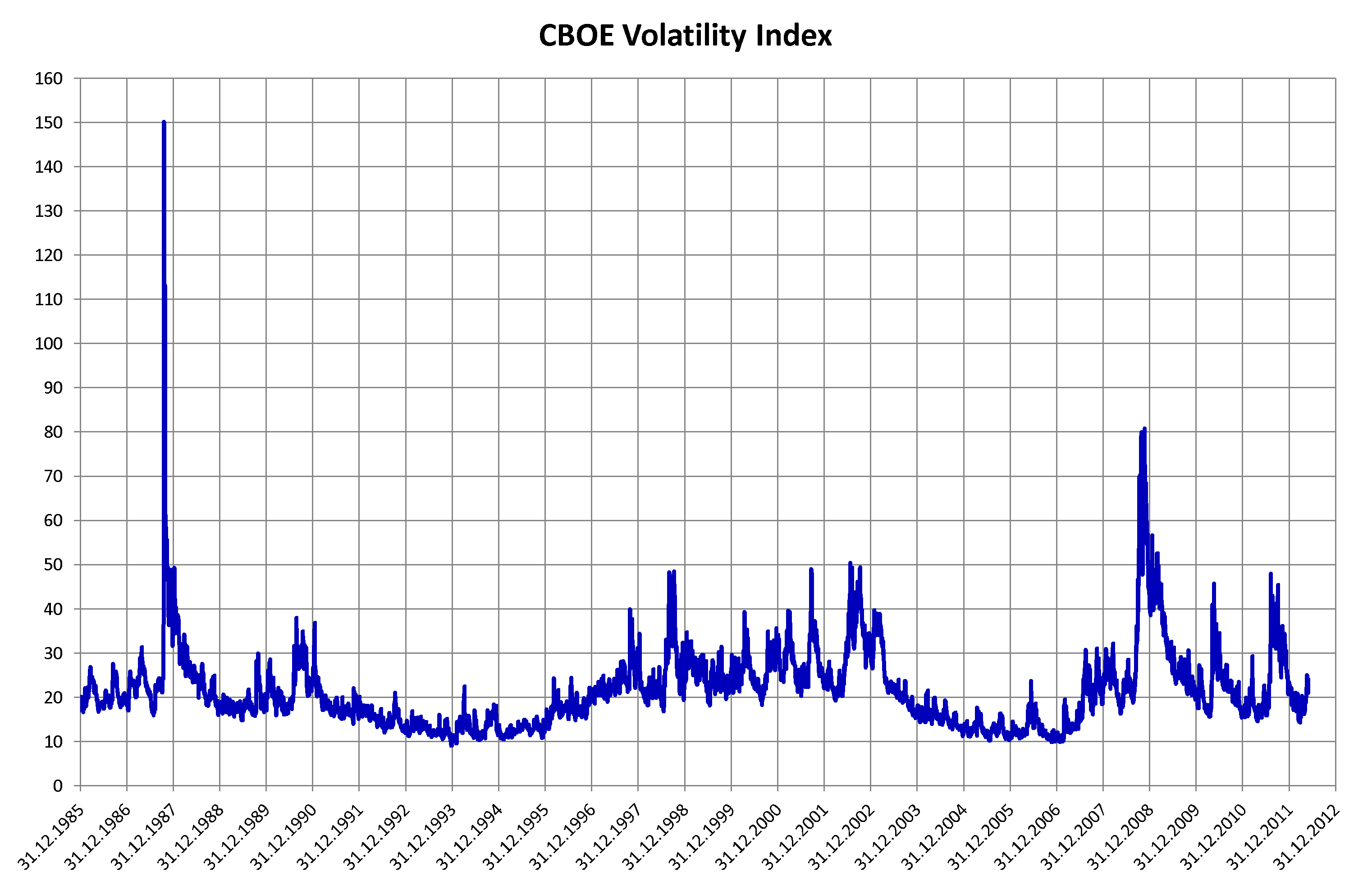

On the other hand, it seems common to assert in the financial world that price volatility is a manifestation of fear. For instance, it seems that VIX (a volatility index based on S&P 500 index options) is often called the fear index or fear gauge. Furthermore, many studies identify possible connections between volatility and political uncertainty, which could be a reason for fear.

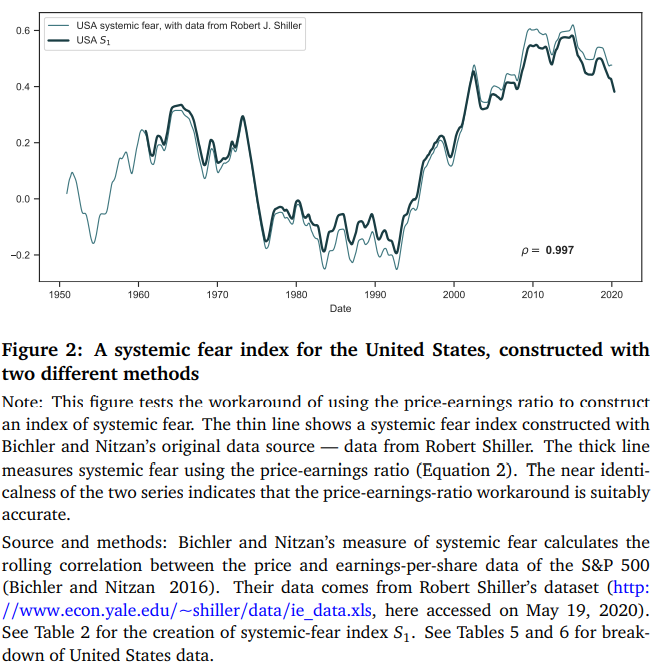

Below I copy paste the evolution of the systemic fear index in the US from McMahon (2021):

and VIX between 1985 and 2012 from Wikipedia:

A proper comparison would be useful, but we can already see from these two figures that they do not necessarily peak at the same time.

However, don’t they both reflect a lack of certainty about the future?

Then, my questions are: how do you think systemic fear and volatility may relate to each other? Are they two manifestations of a same sentiment or do they point out to different kinds of fear? Could volatility be a more sudden manifestation of fear, such as a panic due to rapid (and uncontrolled) changes in the nomos, when discounters can’t easily reach an agreement on prices? While systemic fear would reflect a more profound outlook? Finally, can we think both as revealing periods of indeterminacy (and possible social changes), i.e. when the future is more open than usual?

Best,

Julien

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.