- This topic has 2 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated January 2, 2021 at 11:49 am by .

-

Topic

-

Corporate Power and the Future of U.S. Capitalism [1]

by Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, Research Note, December 2020

http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/664/

Corporate power in the United States has risen to unprecedented levels, but the rate at which this power has grown is decelerating. Both facts have important implications for the future of U.S. capitalism.

According to the theory of capital as power (or CasP for short), the quest for capitalized power – and for more and more of it – is the key driving force of modern capitalism. Capitalists, CasP argues, particularly dominant ones, judge their power differentially. They measure it by the size of their earnings and assets – but they do so not absolutely, but relative to others. Driven by power, their goal is not simply to amass more money, but to do so faster than the average. Their ‘bottom line’ is not maximum accumulation, but differential accumulation.

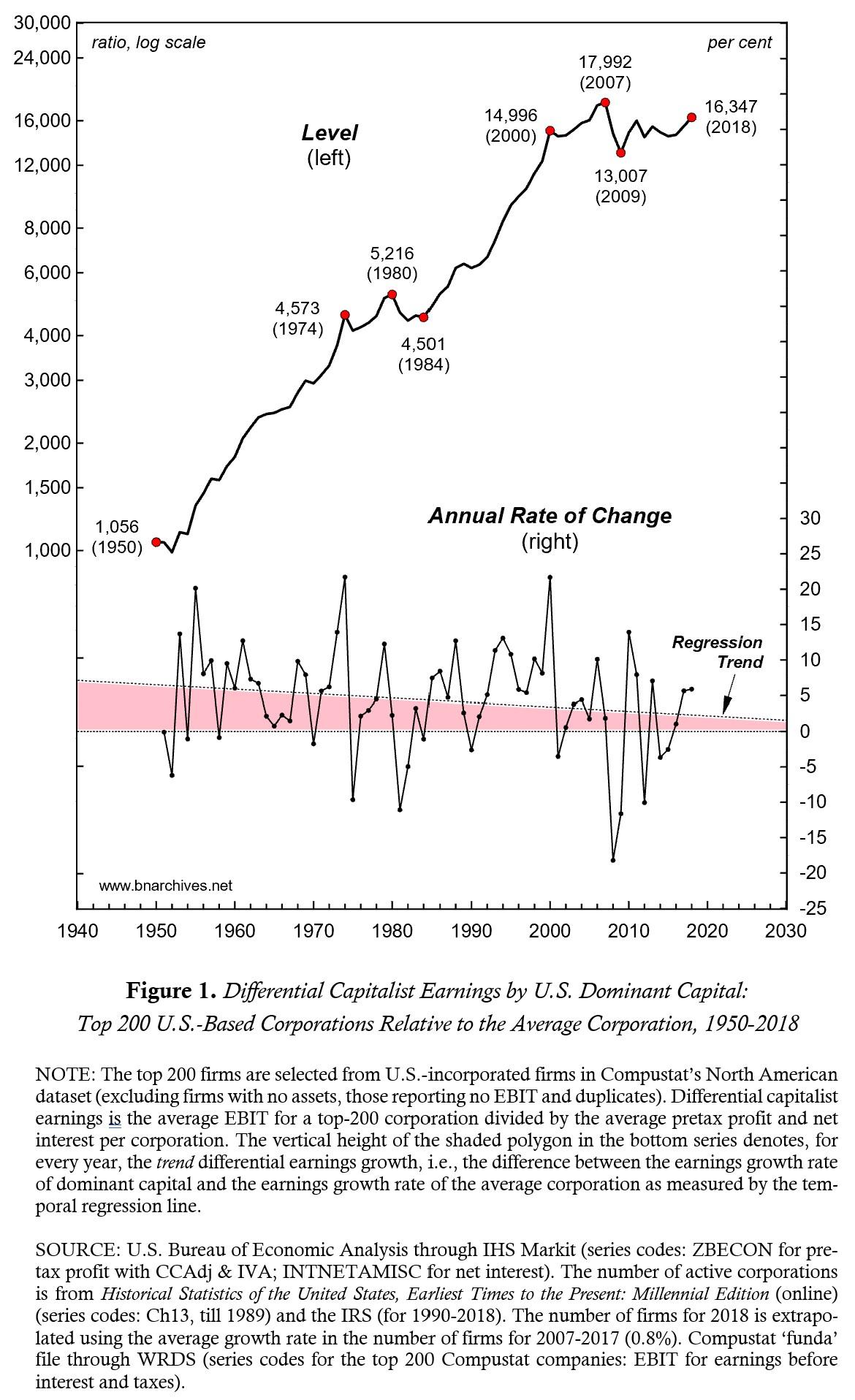

Figure 1 examines this process in the United States. For the sake of presentation, we define ‘dominant capital’ here as the top 200 U.S.-incorporated firms in the North American Compustat dataset, ranked annually by market value. To measure their relative-income-read-differential-power, we compare, for each year, the average earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) received by a top 200 firm to the same earnings recorded by the average U.S. corporation.

The top series, plotted against the left log scale, shows that this differential has grown exponentially. In the early 1950s, the EBIT of a typical dominant capital firm was roughly 1,000 times larger than that of the average U.S. corporation. But having risen at a compounded average annual rate of 4.1 per cent, by 2007 this ratio reached an all‑time high of nearly 18,000.

The uptrend hasn’t been even, though. It stalled twice – first during the period between 1974 and 1984, and then again in the twenty years since 2000. And these lulls weren’t flukes.

The bottom series, plotted against the right scale, shows the annual rate of change of this differential. The temporal regression trend and the shaded polygon underneath it depict a persistent slowdown: in the early 1950s, the differential rose at an average annual rate of over 6 per cent; by the late 2010s, it increased by slightly more than 2 per cent.

This deceleration is not surprising. Dominant capital grows primarily through mergers and acquisitions, and as it does its rate of expansion becomes more and more difficult to sustain. It is one thing for dominant capital firms to double their relative size when they are only 1,000 times bigger than the average. It is quite another to do the same when they are 18,000 larger.

And here lies the problem. Dominant capitalists and corporations cannot stop trying to increase their power. The need to beat the average and grow faster than others is ‘in their nature’. And that has consequences, because rising differential earnings require greater threats, sabotage and violence against the rest of society. If this relentless pressure is not counteracted by effective democratic resistance, U.S. subjects are likely hear much more about the benefits of ‘economies of scale’, the imperatives of ‘global competition’ and the dictates of ‘national security’ – processes that, they will be told, require them to accept ever larger corporations and a much more authoritarian society.

Endnotes

[1] Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan teach political economy at colleges and universities in Israel and Canada, respectively. All their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Work on this paper was partly supported by SSHRC. We thank Daniel Moure for his proofreading.

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.