From Global Oil Politics to Desire via Gas Prices

April 12, 2016

DT Cochrane

The Globe & Mail is reporting that the average fuel efficiency of new vehicles sold in 2014 dropped for the first time since 2011. The coverage suggests this is a response to falling prices at the gas pump.

First, without access to the relevant data for a longer time period, it is difficult to know if the postulated causal link is appropriate. However, taking the coverage at face value, the connection makes sense. As the price of gas goes down, consumers can afford to consume more. Therefore, they can choose to purchase a vehicle that consumes more. This process seemingly affirms the popular understanding of prices and demand. Prices go down, so demand goes up. That understanding bears some resemblance to the mainstream economic theory of supply and demand. However, many of the patently ridiculous assumptions required by the theory, if they were known by the public, would be widely mocked (as they are by university undergrads subject to a micro-economics course). One of those absurd assumptions is perfect information. Within the theory, consumers not only know the price of gas right now, they know the future price of gas for all time.

Another fundamental assumption of neoclassical theory is that desire is exogeneous, meaning it is outside the processes under analysis. An individual comes to the market with their desires intact. Then, they express those desires as a hedonistic utility maximizer responding to prices. Yet, if we dig into the conjecture of the article – demand for less fuel efficient vehicles increased with falling gas prices – we find desires shaped by prices that could hardly be considered emblematic of the neoclassical ideal market.

The existence of the car salesperson ought to be evidence enough that the assumption of perfect information is ridiculous. With access to more information than ever, thanks to the Internet, consumers nonetheless continue to rely on car dealerships staffed by salespeople who are expected to help guide a vehicle purchase. While the buyer undoubtedly has an idea of what they are looking for, they nonetheless consider multiple options, learning about the vehicles in the process. Some of their desires were, and will be, shaped by automobile marketing. Although we may all consider ourselves immune to advertising’s persuasions, its continued existence as a multi-billion dollar undertaking suggests we are wrong. Certain desires will not fall into place until the buyer learns of certain features and considers the differences among various automobiles. Fuel efficiency will be one of those features and it will be considered alongside many others, including appearance, safety, comfort, status and more.

The price of gas enters into this complex of considerations and that price emerges from an enmeshed array of forces, including multiple levels of government, both domestic and foreign as well as numerous corporations, not least the members of Big Oil that undertake their own marketing efforts to influence consumer spending. Attempting to represent all of this via a neoclassical ‘production function’ in order to depict a ‘supply curve’ independent of the ‘demand curve’ would be a maddening and futile exercise. Rather, the emergent price becomes an informant to the buyer’s dynamic desires. Far from an exogeneous factor, desire is a potent endogenous force, which is why so much money and effort is spent trying to understand it. Although capitalists know consumers will spend in general, their interests are less spending-in-general and more differential spending. Toyota wants consumers to spend not just on anything and not even just on any automobile. Toyota wants consumers to spend on its automobiles. That’s why it undertakes market research. That’s why it undertakes advertising campaigns.

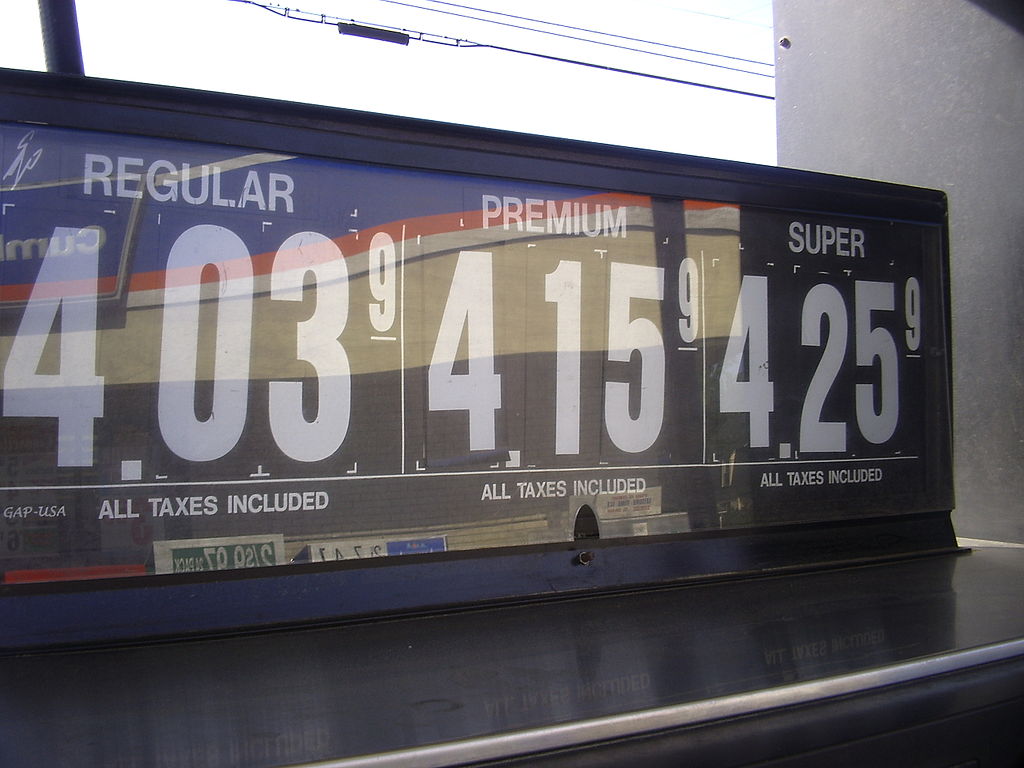

The price of gas, so prominently displayed on a station’s sign, is an incredibly simplified crystallization – a single number – expressing the entire world as it bears on: the extraction, transportation, refinement and storage of oil; the regulations of governments concerning those activities; the lobbying efforts of the corporations to transform those regulations; and the marketing efforts to transform consumers’ desires. Further, that simple expression has its own transformative effect on consumer desires.

Desires, prices and the world are interdependently determined. Although patterns emerge, they do not conform to the now century old abstractions of neoclassical theory, not least because the assumptions that make those abstractions possible – including the independence of desire from price and the world – are as wrong as could be.