An Evolutionary Theory of Resource Distribution (Part 2)

February 21, 2020

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

A 25% chance. That’s the likelihood that when I tell someone I’m searching for a job, they’ll say:

Remember, Blair … to land a job, it’s not what you know that matters. It’s who you know.

OK, maybe I’m exaggerating this chance. Still, it’s an open secret that when it comes to landing a job, it matters who you know. Many people, it seems, like to remind me of this fact.

A 0% chance. That’s the likelihood that when I tell someone I research income distribution, they’ll say:

Remember, Blair … when it comes to income, it’s not what you know that matters. It’s who you know.

Does this discrepancy strike you as weird? It should. It highlights a blind spot in how we think about the distribution of resources. We all know that our social network matters for landing a job. But once we’ve got the gig, we don’t think about how our relationships determine our income.

But what if we did think about the social nature of income? What would the resulting theory of resource distribution look like? I explore this question here using the evolutionary framework developed in Part 1 of this series.

To recap, my thesis is that humans have a dual nature. We are both selfish and selfless. This duality, I argue, stems from a tension between two levels of natural selection. At the group level, selfless behavior is advantageous. But at the individual level, selfish behavior is advantageous. This tension, I believe, is key to understanding how we distribute resources.

In An Evolutionary Theory of Resource Distribution Part 1, I explored this tension by looking at how groups compete with each other and suppress competition internally. In this post, I look at the same tension from the opposite angle. I discuss how individuals cooperate to build groups, and how this cooperation gets used by individuals for selfish gain.

We’ll journey first to the fantasy world of neoclassical economics to see what’s wrong with mainstream theory. Then we’ll journey to the real world and look at how humans use social relations to distribute resources.

The neoclassical bartender

When we study resource distribution, neoclassical economics is always the elephant in the room. It’s the lumbering theory that, despite many bullet wounds, refuses to die. I’ve previously called the neoclassical theory of distribution a thought virus and an ideology. Here, I’ll treat it as the punchline to a joke.

A janitor and a CEO walk into a neoclassical bar. Envious of the CEO’s exorbitant income, the janitor hits the CEO. A brawl ensues. What does the neoclassical bartender say to stop the fight?

“Stop fighting. You both get paid what you produce.“

OK, this punchline isn’t very funny. But it’s the line delivered by neoclassical economist John Bates Clark. At the end of the 19th century, social ferment was in the air. In response to this ferment, Clark developed a theory of income distribution that essentially said to society: “Stop fighting. Everyone gets paid what they produce”. Here’s how Clark put his bartender punchline:

It is the purpose of this work to show that the distribution of the income of society is controlled by a natural law, and that this law, if it worked without friction, would give to every agent of production the amount of wealth which that agent creates. (John Bates Clark in The Distribution of Wealth)

In one of the great ironies of history, Clark’s punchline managed to become a respectable scientific theory (at least among economists). The punchline goes by the name of ‘marginal productivity theory’. It proposes that in a competitive market, every person receives exactly what they produce.

When he delivered his punchline, Clark’s main interest was the income split between workers and capitalists. Clark wanted to show that capitalists got what their property produced, and hence deserved their income. Only later did neoclassical economists focus on income differences between workers. In the 1960s, theorists like Gary Becker and Jacob Mincer proposed that workers’ income was proportional to their ‘human capital’. This human capital was a stock of skills that made workers more productive.

Soon after it was proposed, however, human capital theory ran into trouble. Ironically, it was human capital pioneer Jacob Mincer who revealed the problem. In his initial work, Mincer defined human capital restrictively as an individual’s years of formal schooling. But Mincer soon found that formal schooling explained very little about individual income. Here’s Mincer admitting the problem:

Simple correlations between earnings and years of schooling are quite weak. Moreover, in multiple regressions when variables correlated with schooling are added, the regression coefficient of schooling is very small. (Jacob Mincer in Progress in Human Capital Analysis of the Distribution of Earnings.)

In response to this empirical failure, many economists doubled down. Instead of abandoning their theory, they broadened their definition of human capital so that it could explain everything and anything about income.

Take, for example, Gregory Mankiw’s bestselling economics textbook, Principles of Microeconomics. In it, Mankiw defines human capital as “the accumulation of investments in people”. With vague definitions like this, human capital theory became immune to evidence. Sadly, neoclassical economists didn’t see this as a problem.

Neoclassical Robinson Crusoe

When it comes to explaining resource distribution, neoclassical theory is missing something obvious. To see what’s missing, we’ll tell another joke.

A neoclassical version of Robinson Crusoe gets stranded on a desert island. How much does his standard of living decrease from before he was stranded?

None. Crusoe took his human capital with him!

Again, this punchline isn’t very funny. But it’s a true representation of human capital theory, which assumes that people carry their income-earning potential around with them. All that matters for workers’ income is their stock of human capital.

Maybe it’s just me, but human capital theory seems to be missing something big. Hmmm .. what is it? Oh, just the rest of society!

Neoclassical theory assumes, quite literally, that the rest of society is irrelevant for determining one’s income. In a competitive market, the theory says that we all get what we produce [1]. If some people produce more than others, it’s because they have more human capital, or own more physical capital. The social context, in other words, is irrelevant to one’s income. Put Robinson Crusoe in London or strand him on an island … it doesn’t matter. His skills stay the same, so his income stays the same.

The message of neoclassical economics is that we’re all self-sufficient Robinson Crusoes — islands unto ourselves. This sounds like an April Fool’s day joke, but it’s not. It’s what passes for science in the discipline of economics. Neoclassical economists have built a towering theoretical edifice on the idea that there’s no such thing as society.

Evolutionary microfoundations

To build a more realistic theory of resource distribution, we need a new ‘microfoundation’ for economics. This is the term economists use to describe their assumptions about human behavior. Most economists assume that humans are purely selfish. But this idea has outlived its usefulness.

A better approach, I believe, is to assume that humans are both selfish and selfless. And we should take a hint from biologists and ground this duality in an evolutionary framework. Yes, I’m arguing that the principles of evolutionary biology should form the microfoundation of economics.

I’ll base my approach on a theory called group selection (sometimes called multilevel selection). According to this theory, the duality of human nature stems from an evolutionary conflict between two ‘levels’ of natural selection. Selfishness stems from selection at the individual level. Altruism stems from selection at the group level.

E.O. Wilson and David Sloan Wilson summarize this tension between individuals and groups in a succinct motto:

Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary. (Source)

I propose that we use this principle as the ‘microfoundation’ of economics. Out with the old assumption that individuals are selfish utility maximizers. In with the evolutionary hypothesis that humans are both selfish and selfless — a duality shaped by the tension between individual versus group benefit.

Relations: the building block of groups

The building block of our evolutionary theory should be the human relation. By forming networks of relations, humans are able to form groups. These relations then determine how resources are distributed within groups.

To develop our ideas, we’ll look at a group of two people. We’ll call them Alice (A) and Bob (B).

Figure 1: A group of two people, Alice and Bob

Now we ask ourselves — what kind of relation do Alice and Bob have?

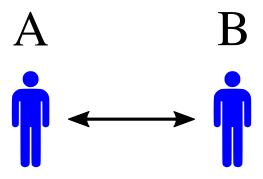

One possibility is that they have a purely altruistic relation. This means that Alice and Bob respect each other’s will. They don’t do anything as a group unless they can both agree on it. We’ll represent this purely altruistic relation using a double-headed arrow. The two heads indicate that influence is symmetrical. Alice influences Bob as much as Bob influences Alice.

Figure 2: A Purely Altruistic Relation

In the real-world, the closest we get to a purely altruistic relation is probably the bond between two people who are ‘in love’. While we should celebrate love, we should also realize that most human relations are not purely altruistic. Instead, pure altruism is an ideal. It’s one end of the spectrum of human relations.

So what’s the opposite end of the spectrum?

It’s tempting to say that the opposite of the purely altruistic relation would be the purely selfish relation. But the problem with this response is that a purely selfish relation is actually no relation at all. If two people pursue only their own selfish ends, we can hardly call this a relationship. It’s just an aggregate of selfish individuals.

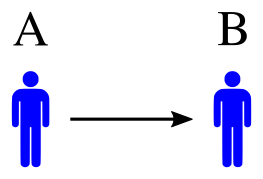

No, the opposite of a purely altruistic relation isn’t a purely selfish relation. It’s a pure power relation. In such a relation, one person acts selfishly while the other person acts altruistically. But in power relations, ‘altruism’ takes a special form. We call it submission. The altruistic person submits to the will of the dominant person.

We’ll represent a pure power relation using a single-headed arrow. The direction of the arrow indicates the direction of influence — the flow of power. In the relation below, Alice has power over Bob.

Figure 3: A Pure Power Relation

In a pure power relation, power is absolute. If Alice says “jump off a cliff”, Bob jumps off a cliff. Like pure altruism, pure power is an ideal. In the real world, the closest thing to a pure power relation is probably the bond between a master and slave. A slave must obey their master, even to their own detriment.

Pure altruism and pure power, then, are idealized relations that define the spectrum of human bonds. We’ll use this spectrum to think about how groups distribute resources.

Dividing the pie

To explore how groups distribute resources, we’ll return to Alice and Bob. Imagine that Alice and Bob are a group that together exploits resources. One day, the two of them find an apple pie. How do they divide it up?

The answer depends on Alice and Bob’s relation.

Let’s first imagine that Alice and Bob treat each other as equals. They have a purely altruistic relation. In this case, the two of them will likely divide the pie equally. Why? Because every decision depends on consensus. If Alice wants to take more resources than Bob, she must convince Bob to give up his share. That’s a hard sell if Bob thinks himself equal to Alice.

The only convincing reason for Alice to take more resources than Bob is if she needs more. Suppose Alice is an endurance athlete and Bob is a couch potato. In this case, Alice needs more food, and Bob is likely to let her have it. So in purely altruistic relations, resource distribution will follow the communist ethos: to each according to their need.

Now let’s imagine that Alice and Bob have a pure power relation. Alice has absolute power over Bob. Now how do they divide the pie?

It’s tempting to say that Alice and Bob would follow what I’ve called the red-claw ethos: to each according to their ability to take (see Part 1 for details). But there’s a problem here. The red-claw ethos is about individual competition — a war of all against all. It’s how resources are distributed in purely selfish relations. But this mutual competition is not how power relations work. Instead, in power relations only one person acts selfishly. The other person acts altruistically by submitting to the will of their dominant partner.

In our example, Bob submits to Alice’s will. This submission is key to understanding how resources get distributed. When Bob submits to Alice, he gives her complete control over the resource pie. Alice could be a despot and hoard everything. Or she could be a benevolent dictator and give Bob his fair share. The choice is hers.

In pure power relations, then, resource distribution is determined by the whim of the dominant individual. Still, there is a regularity to how those with power distribute resources. Even the most selfless individuals inevitably use their influence for personal gain. Power, as they say, corrupts.

Here’s how it happens. Suppose that Alice has absolute power over Bob. Suppose also that Alice is a fervent Marxist, and believes in the communist ethos. So she initially shares resources equally with Bob. So far so good.

But as time goes by, Alice’s power goes to her head. She starts to feel that she’s not like Bob. Because of her power, Alice starts to believe that she’s special. She has innate abilities that Bob doesn’t have — abilities that Bob could never have. And because she has these abilities, Alice thinks to herself, “I deserve more resources than Bob”. And so she takes more resources — a little at first but more over time. Slowly Alice turns from a benevolent dictator to a gluttonous despot. It’s a story as old as time.

The power ethos

The moral of our Alice and Bob story is that people inevitably use their power to enrich themselves. In power relations, then, resource distribution has its own ethos. We’ll call it the power ethos:

Power ethos: To each according to their social influence.

When I’ve discussed the power ethos with mainstream economists, they’ve reacted with bewilderment. The problem, I’ve realized, is that economists reject the idea of a social cause. Instead, they insist that resource distribution must be tied to characteristics of individuals or their property. Philosophers have a name for this thinking. They call it methodological individualism. Geoffrey Brennan and Gordon Tullock summarize how the philosophy works in economics:

n modern economics … the ultimate unit of analysis is always the individual; more aggregative analysis must be regarded as only provisionally legitimate. (Source)

Economists are bewildered by the power ethos because power is not a property of the individual. Instead, power is a social relation between people. And trying to understand social relations, it seems, produces error messages in the brains of economists. So to them, the power ethos is incoherent.

But while incoherent to mainstream economists, the power ethos makes perfect sense in our evolutionary theory. In fact, the essence of our theory is that there is a conflict between social (group) goals and individual goals. Let’s look at the power ethos through this evolutionary lens.

Power is a social relation shared by both groups and individuals. At the group level, power is a mode of organization — a way to coordinate human activity. At the individual level, power is a tool for selfish gain — something to be accumulated for personal enrichment.

This duality of power creates a tension between levels of natural selection. Concentrating power may be good for the group but not good for (some) individuals within the group. Likewise, when individuals use their power to enrich themselves, this is good for (some) individuals within the group, but not good for the group as a whole.

Power is a double-edged sword that cuts to the core of our dual nature as humans.

How does centralized power benefit groups?

So why might centralized power benefit groups? Peter Turchin thinks it’s because centralized power allows groups to get bigger. When power has a nested structure (a hierarchical chain of command), it limits the need for social interaction. In a hierarchy, you need to interact only with your direct superior and direct subordinates. This structure, Turchin argues, allows humans to sidestep biological limits in our ability to organize. Centralized power allows group size to grow without increasing the need for social interaction.

If Turchin is correct, it still begs a question. Why are bigger groups better? Turchin’s answer is that big groups have a military advantage over small groups. “Providence”, the saying goes, “is always on the side of the big battalions”. Turchin argues that over the last 10,000 years, large hierarchical groups tended to defeat small egalitarian groups. With each defeat, concentrated power spread as an organizing principle.

Turchin’s argument is compelling, and I agree with most of it. But I think it’s missing one big ingredient — energy. The availability of energy, I believe, is a key constraint on the growth of large groups, and thus a constraint on the concentration of power. I’ll explore this idea in a future post.

Centralized power as convergent evolution?

Humans’ use of centralized power as a coordination tool is not unique in nature. In fact, it may be an example of convergent evolution. Think of the evolution of multicellular animals. As they’ve gotten bigger, animals have all evolved centralized control as an organizing principle inside their bodies.

The human body, for instance, isn’t an aggregate of autonomous cells. Instead, it’s a network of cooperating cells that are controlled by the central nervous system. The cells of the brain, in effect, have power over other cells. When brain cells say “jump”, muscle cells say “how high”.

There is, however, a fundamental difference between cells in the body and individual humans in groups. Body cells don’t use their power for selfish gain. We never catch brain cells using their control of the nervous system to take resources from muscle cells. (If we do, it signals that something has gone very wrong in the body). We don’t see this because body cells are altruistic. So even though the body is centrally controlled, the communist ethos prevails. Each cell gets exactly the resources it needs.

In contrast to the cells in our body, individual humans are not purely altruistic. We may be social animals, but we still have a strong selfish streak. (On the ladder of sociality, humans rank far below the cells in our own bodies). So when human groups centralize power, individuals predictably use their power for personal gain. Instead of the communist ethos, then, we get the power ethos. Each person gets what their social influence allows them to take.

This is why power is a double-edged sword.

The double-edged sword

Concentrated power is no panacea for groups. If it were, we’d all be living in totalitarian regimes. Yes, power is a tool for coordination. But it’s also a tool for despotism. And this despotism can easily undermine the coordinating benefits of power.

Here’s an example. Imagine two large armies meet to do battle. Both armies are the same size and have the same weapons. And both armies are organized using concentrated power. On the surface, these armies appear equally matched. But below the surface, there’s a gaping difference. One army is commanded by a gluttonous despot who keeps his subordinates in rags. We’ll call this the ‘slave army’. The other army is commanded by a benevolent dictator who shares resources equally with his soldiers. We’ll call this the ‘professional army’.

Which army wins the battle?

I’d wager on the professional army. The problem for the slave army is that the leader’s despotism undermines his chain of command. Think about it. Would you put your life on the line for a commander who kept you in rags? I wouldn’t. But I might put my life on the line for a commander who shared resources with me.

The professional army probably has better morale than the slave army, and thus a stronger chain of command. The professional army fights as a unit, keeping the group advantage of centralized power. In contrast, the slave army has a tenuous chain of command. At the first sign of misfortune, the slaves will abandon their despotic leader to whom their allegiance is thin. As the battle rages, the slave army collapses and gets slaughtered.

This is a hypothetical example. But there is real-world evidence that inequality undermines groups’ ability to compete. The evidence comes, not surprisingly, from sports — the modern surrogate for violent conflict. In his book Ultrasociety, Peter Turchin notes that sports teams with more equal pay tend to win more games. Here’s Turchin describing work by Frederick Wiseman and Sangit Chatterjee:

Frederick Wiseman and Sangit Chatterjee sorted the Major League Baseball teams into four payroll classes, ranging from those with the biggest disparities to those with the smallest. Between 1992 and 2001, teams in the most equal class won an average of eight more games per season than those in the most unequal class. The corrosive effect of inequality on cooperation is not limited to baseball. The same effect was observed when researchers analyzed the performance records of soccer teams in Italy and Japan. (Peter Turchin in Ultrasociety)

If inequality undermines sports teams’ performance, we expect it to do the same among warring groups. The lesson is that when groups concentrate power, they must walk a fine line. They must reap the coordinative benefits of power while avoiding the perils of despotism.

Pathways to power

While power is a double-edged sword for groups, it’s a panacea for the individuals who accumulate it (until their group collapses because of their despotism). Amassing power is a proven way to increase reproductive success [2]. So it’s no wonder that humans (some of us, anyway) have an urge to seek power. If a behavior leads to reproductive success, organisms will develop an urge to do it.

But what exactly do we mean when we say that an individual ‘accumulates power’? Ultimately, my goal here is to develop a quantitative theory of resource distribution. To do this, we need to measure the accumulation of power.

With this measurement in mind, I’m going to discuss three ‘pathways to power’ [3]. These are ways that individuals can increase their social influence within a group.

Pathway to Power 1: Make your subordinates more submissive

One way to increase your power is to make your existing subordinates more submissive. By doing so, you make your power more absolute.

An obvious way to do this is to coerce your subordinates. If I hold a gun to your head, you’ll immediately become more submissive. As totalitarian regimes have discovered, coercion is a good way to make people more obedient.

But while potent, coercion is an expensive way to increase your power. The more you coerce someone, the more they’ll dream of killing you. This is the fear of every despot — that their subordinates will turn on them. So while coercion can exact obedience, it requires constant vigilance. Ignore your coerced subordinates for a moment and you may find a dagger in your back.

A less expensive way to make your subordinates more submissive is to turn to the power of ideas. Convince your subordinates that you have the legitimate right to command them and you immediately increase your power.

What kind of ideas work? Convincing your subordinates that you speak for God seems to do the trick. Convincing your subordinates that you are a God is even better. Regardless of the content of your ideology, what matters is its virulence. To work, your ideology must infect the minds of your subordinates. It must convince them that your power is legitimate.

Whether you use coercion or ideology (or both), making your subordinates more submissive can increase your power. That being said, this approach is not an effective way to accumulate power. Why? Because having absolute power over a few subordinates hardly makes you Napoleon. To achieve great power, you need to become the master of many. You need to accumulate subordinates.

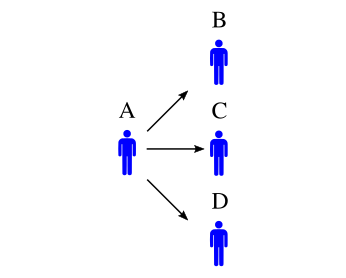

Pathway to Power 2: Accumulate direct subordinates

With Napoleon as your inspiration, you set out to accumulate subordinates. How do you do it? One way is to accumulate direct subordinates.

A direct subordinate is someone who is directly under your control. They listen to you and no one else. Figure 4 shows an example of this pathway to power. Here, our budding despot Alice has accumulated 3 subordinates — Bob (B), Charlotte (C) and David (D). In idealized form Bob, Charlotte and David obey Alice and ignore each other.

Figure 4: Accumulating direct subordinates

While simple, there are obvious limits to this pathway to power. Even the most charismatic person will find it hard to maintain direct power relations with hundreds of people. Yet to be powerful like Napoleon, you need hundreds of thousands of subordinates.

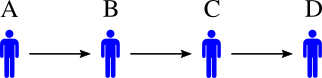

Pathway to Power 3: Accumulate indirect subordinates

If you’re not satisfied with the number of subordinates you can control directly, the next step is to encourage your subordinates to find their own subordinates. By doing so, you accumulate indirect subordinates. Figure 5 shows an example. Here Alice controls Bob, who controls Charlotte, who controls David.

Figure 5: Accumulating indirect subordinates

We assume here that power is ‘transitive’. So if Bob controls Charlotte and Alice controls Bob, then Alice also controls Charlotte. When power is transitive, it forms a chain of command. By virtue of this chain of command, Alice has 3 subordinates (1 direct and 2 indirect).

The advantage of accumulating indirect subordinates is that you don’t need to manage relations with many people. In our example, Alice directly commands only one person — Bob. To wield power, she gives orders to Bob, who then passes these orders down the chain of command. This is far easier than giving orders to hundreds of people.

The disadvantage of having indirect subordinates, however, is that power isn’t perfectly transitive. Power gets diluted as it’s passed down the chain of command. So when Alice says “jump”, there’s no guarantee that David will get the message. The intermediaries in the chain of command (Bob and Charlotte) have their own agendas which may be different from Alice’s. So having indirect subordinates still requires work. You have to maintain the chain of command so that power flows smoothly.

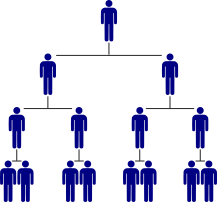

The road to hierarchy

If you’re a budding Napoleon, you’ve likely realized that the best way to accumulate power is to use all three pathways: make your subordinates extremely submissive, accumulate direct subordinates, and encourage your subordinates to accumulate subordinates.

When you pursue all three pathways to power, what do you get? In a word, hierarchy.

A hierarchy is a network in which every relation is a power relation. To maintain the hierarchy, you must make sure your subordinates are submissive (pathway 1). Next, you encourage all of your subordinates to command multiple subordinates of their own. This combines pathways 2 and 3, and leads to the quintessential feature of a hierarchy — the branching chain of command.

Figure 6: The branching chain of command in a hierarchy

It’s by commanding a growing hierarchy that you can accumulate power that rivals Napoleon’s. Think about the structure of hierarchy. As each new layer of hierarchy is added, the number of subordinates you command grows exponentially.

Suppose you start out as a bit player who controls 4 subordinates. But as a budding Napoleon, you soon attract more people to your cause. You convince each of your subordinates to get 4 subordinates of their own. Now you have 20 subordinates (4 direct + 16 indirect). Repeat this process again and you have 84 subordinates (4 + 16 + 64). Repeat again and you have 340 subordinates (4 + 16 + 64 + 256). It doesn’t take long (about 10 levels of hierarchy) before you have millions of subordinates.

Now you have power that rivals Napoleon’s. And our evolutionary theory predicts that you’ll use it to your advantage. You’ll use your immense power to take an exceptional share of the resource pie.

It’s not what you know that matters …

I began this post by noting that when I discuss my research with friends, they don’t comment that one’s income is about ‘who you know’. This, I argued, is a sign that most people don’t think about the social nature of income. Most of us prefer to believe that our income is about our skill, not our place in society.

But with a bit of evolutionary reasoning, it becomes clear that our relations must be what drives the distribution of income inside groups. Moreover, when groups organize using power relations, we have a clear prediction for how income should be distributed. I’ve called this prediction the power ethos: to each according to their social influence.

Hierarchies, I’ve argued, are the quintessential tool for concentrating power. In them, the power ethos should dominate. In other words, in a hierarchy it’s not what you know that shapes your income. It’s who you control.

Now, I realize that I haven’t given you a shred of evidence that the power ethos is true — that income in hierarchies correlates with social influence. There is evidence, I assure you. But to see it, you’ll have to wait for the next instalment of this series. Stay tuned.

Notes

[1] ‘Getting what you produce’. You’ve probably noticed that in the real world, very few people (subsistence farmers aside) literally consume what they produce. Musicians don’t exclusively consume their music. And bakers don’t exclusively consume their bread. In the real world, we exchange many different commodities with one another. Not so in neoclassical theory. Clark’s theory of marginal productivity only works in a world with one commodity. Think of it as the widget world. Everybody makes widgets. And everybody consumes widgets. In this world, everyone literally consumes what they produce, because they all produce the same thing.

[2] The anthropologist Laura Betzig has spent much of her career studying how hierarchical power leads to reproductive success. Check out her book Despotism and Differential Reproduction: A Darwinian View of History.

[3] I’m borrowing the term ‘pathways to power’ from Brian Hayden, who used it as the title of a paper about the origin of inequality. Douglas Price and Gary Feinman later used the phrase as the title of their book on the same topic.