Productivity Does Not Explain Wages

June 14, 2020

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

Does productivity explain income? I asked this question in a previous post. My answer was a bombastic no. In this post, I’ll dig deeper into the reasons that productivity doesn’t explain income. I’ll focus on wages.

The evidence

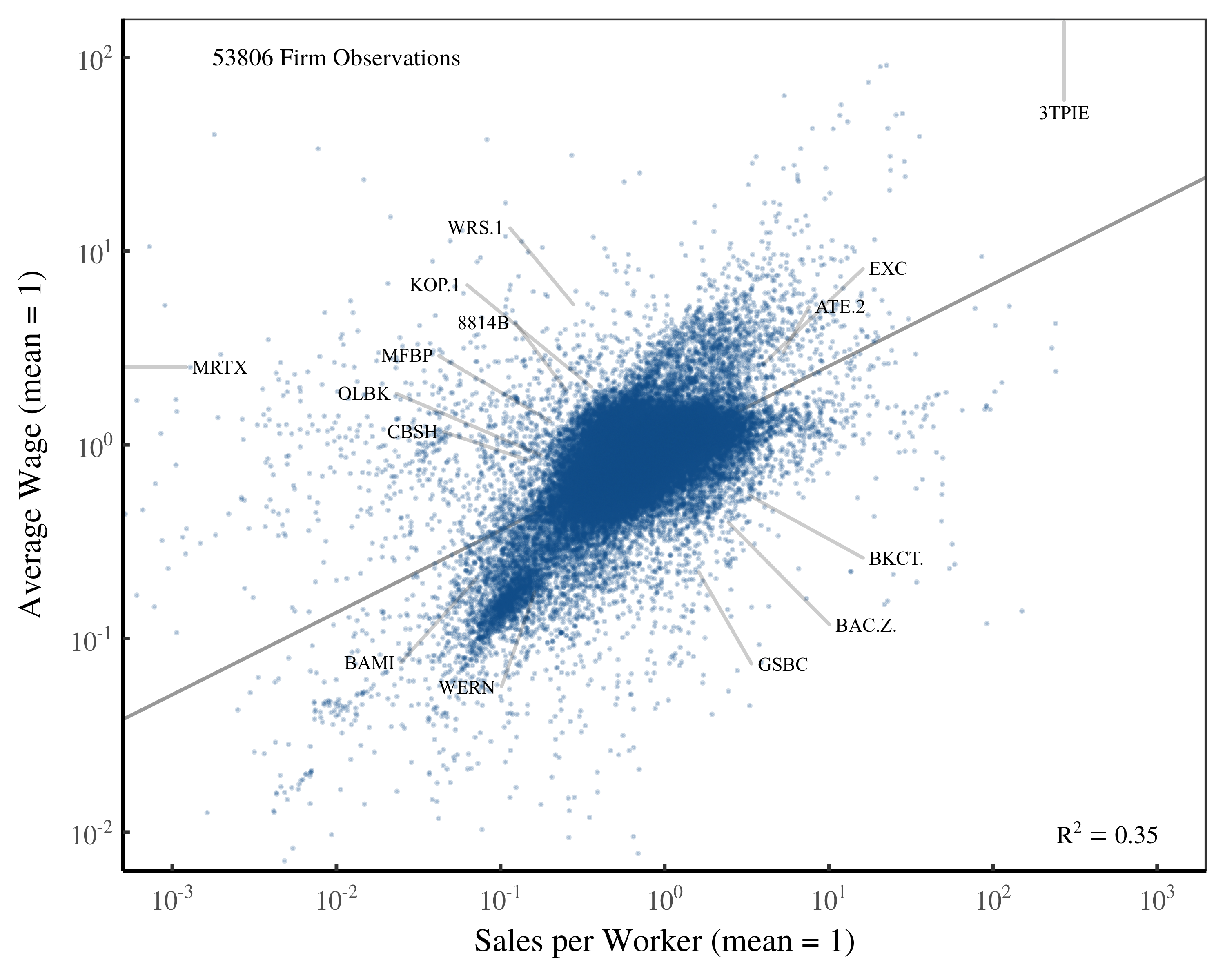

Let’s start with the evidence trumpeted as proof that productivity explains wages. Looking across firms, we find that sales per worker correlates with average wages. Figure 1 shows this correlation for about 50,000 US firms over the years 1950 to 2015.

Figure 1: The correlation between a firm’s average wages and its sales per worker. Data comes from Compustat. To adjust for inflation, I’ve divided wages and sales per worker by their respective averages (in the firm sample) in each year. I’ve shown stock tickers for select firms.

Figure 1: The correlation between a firm’s average wages and its sales per worker. Data comes from Compustat. To adjust for inflation, I’ve divided wages and sales per worker by their respective averages (in the firm sample) in each year. I’ve shown stock tickers for select firms.

Mainstream economists take this correlation as evidence that productivity explains wages. Sales, they say, measure firms’ output. So sales per worker indicates firms’ labor productivity. Thus the evidence in Figure 1 indicates that productivity explains (much of) workers’ income. Case closed.

The problem

Yes, sales per worker correlates with average wages. No one disputes this fact. What I dispute is that this correlation says anything about productivity. The problem is simple. Sales per worker doesn’t measure productivity.

To understand the problem, let’s do some basic accounting. A firm’s sales equal the unit price of the firm’s product times the quantity of this product:

Sales = Unit Price × Unit Quantity

Dividing both sides by the number of workers gives:

Sales per Worker = Unit Price × Unit Quantity per Worker

Let’s unpack this equation. The ‘unit quantity per worker’ measures labor productivity. It tells us the firm’s output per worker. For instance, a farm might grow 10 tons of potatoes per worker. If another farm grows 15 tons of potatoes per worker, it unambiguously produces more potatoes per worker (assuming the potatoes are the same).

The problem with using sales to measure productivity is that prices get in the way. Imagine that two farms, Old McDonald’s and Spuds-R-Us, both produce 10 tons of potatoes per worker. Next, imagine that Old McDonald’s sells their potatoes for [/latex]100 per ton. Spuds-R-Us, however, sells their potatoes for [/latex]200 per ton. The result is that Spuds-R-Us has double the sales per worker as Old McDonald’s. When we equate sales with productivity, it appears that workers at Spuds-R-Us are twice as productive as workers at Old McDonald’s. But they’re not. We’ve been fooled by prices.

The solution to this problem seems simple. Rather than use sales to measure output, we should measure a firm’s output directly. Count up what the firm produces, and that’s its output. Problem solved.

So why don’t economists measure output directly? Because the restrictions needed to do so are severe. In fact, they’re so severe that they’re almost never met in the real world. Let’s go through these restrictions.

Restriction 1: Firms must produce identical commodities

To objectively compare productivity, you have to find firms that produce the same commodity. You could, for instance, compare the productivity of two farms that produce (the same) potatoes. But if the farms produce different things, you’re out of luck.

Here’s why. When firms produce different commodities, we need a common dimension to compare their outputs. The problem is that the choice of dimension affects our measure of output.

To see the problem, let’s return to our two farms, Old McDonald’s and Spuds-R-Us. Suppose that Spuds-R-Us produces 10 tons of potatoes per worker. Tired of growing potatoes, Old McDonald’s instead grows 5 tons of corn per worker. Which workers are more productive?

The answer depends on our dimension of analysis.

Suppose we compare potatoes and corn using mass. We find that Spuds-R-Us workers (who produce 10 tons per worker) are more productive than Old McDonald’s workers (who produce 5 tons per worker).

Now suppose we compare potatoes and corn using energy. Furthermore, imagine that corn has twice the caloric density of potatoes. Now we find that workers at Spuds-R-Us (who produce half the mass of food at twice the caloric density) have the same labor productivity as Old McDonald’s workers.

The lesson? Unless two firms produce the same commodity, productivity comparisons are subjective. They depend on the choice of dimension.

Restriction 2: Firm output must be countable

When you read economic textbooks, it’s clear that the discipline of economics is stuck in the 19th century. Firms, the textbooks say, produce stuff.

But what about all those other firms that don’t produce stuff? What is their output? What, for instance, is the output of Goldman Sacks? What is the output of a high school? What is the output of a hospital? What is the output of a legal firm?

Yes, these institutions do things. But it defies reason to give these activities a ‘unit quantity’. In other words, it defies reason to quantify the output of these institutions.

Restriction 3: Firms must produce a single commodity

Complicating things further, we can objectively measure output only when firms produce a single commodity. If a firm produces two (or more) commodities, its output is affected by how we add the commodities together.

To see the problem, let’s return to Old McDonald’s and Spuds-R-Us. Suppose that both farms have diversified their production. Spuds-R-Us produces 5 tons of potatoes and 1 ton of corn per worker. Old McDonald’s produces 1 ton of potatoes and 5 tons of corn. Which workers are more productive?

The answer depends on our dimension of analysis. In terms of mass, both farms produce 6 tons of food per worker. So labor productivity appears the same. But suppose we measure the output of energy. Again, we’ll assume that corn has double the caloric density of potatoes. Suppose corn contains 2 GJ (gigajoule) per ton, while potatoes contain 1 GJ per ton. Now we find that Old McDonald’s workers are about 60% more productive than workers at Spuds-R-Us. Here’s the calculation:

Spuds-R-Us:

5 tons potato × 1 GJ / ton + 1 ton corn × 2 GJ / ton = 7 GJ

Old McDonald’s:

1 ton potato × 1 GJ / ton + 5 ton corn × 2 GJ / ton = 11 GJ

This ‘aggregation problem’ is why the neoclassical theory of income distribution assumes a single-commodity world — a world in which everyone produces and consumes the same thing. In this one-commodity world, we can measure productivity unambiguously. In the real world (with many commodities) productivity depends on our choice of dimension.

The severity of the problem

Let’s take stock. If we want to measure productivity objectively, the restrictions are severe:

- Firms must produce the same commodity

- This commodity must be countable

- Firms must produce only one commodity

These conditions are so stringent that they’re rarely met in the real world. This is a bit of a problem for neoclassical theory. It proposes that everyone’s income is explained by their productivity. But only in the rarest of circumstances can we measure productivity objectively.

It’s hard not to laugh at this predicament. It’s like Newton proclaiming that gravitational force is proportional to mass. But in the next sentence he realizes that mass can be measured only in the rarest of circumstances.

The neoclassical sleight of hand

Neoclassical economists don’t think of themselves as Newtons who can’t measure mass. Instead, economics textbooks don’t even mention the problems with measuring productivity. In these textbooks, all seems well in neoclassical land.

But all is not well. Neoclassical economists perpetuate their fantasy by relying on a sleight of hand. Here’s what they do.

First, economists argue that the purpose of all economic activity is to give consumers utility. Buy a potato and you get utility. Buy a cigarette and you get utility. Utility, economists say, is the universal dimension of output. By measuring utility, we can compare the output of any and all firms (no matter what they produce).

After proclaiming that utility is the universal dimension of output, economists pull their trick. Utility, they say, is revealed through prices. So a painting worth [/latex]1000 gives the buyer 1000 times the utility as a [/latex]1 potato.

With this thinking in hand, economists see that a firm’s sales measure its output of utility:

Sales = Unit Price × Unit Quantity

Sales = Unit Utility × Unit Quantity = Gross Utility

So sales become a universal measure of utility, and utility is the universal measure of output. Now, when we compare sales per worker to wages (as in Figure 1), economists proclaim that we’re comparing productivity to wages.

Except we’re not.

The problem is that this whole operation is circular. The idea that prices reveal utility is a hypothesis. And as every good scientist knows, you can’t use your hypothesis to test your hypothesis. But that’s what neoclassical economists do. They assume that one aspect of their theory is true (the link between prices and utility) to test another aspect of their theory (the link between productivity and income). This is a big no no.

Why do economists use this circular reasoning? Probably because they don’t know they’re doing it. Economists take as received wisdom the idea that prices reveal utility. But this is just a hypothesis. In fact, it’s a bad hypothesis. Why? Because we can never measure utility independently of prices.

Why are sales related to wages?

Whenever I go through the logic above, mainstream economists will retort: “But look at the correlation between wages and sales! How can this not show that productivity explains wages?” Their reasoning seems to be that, absent an alternative explanation, this correlation must support their hypothesis.

In No, Productivity Does Not Explain Income, I gave an alternative explanation. The correlation between wages and sales per worker, I argued, follows from accounting principles.

Sales isn’t a measure of output. It’s an income stream. Once earned, this income gets split by the firm into different categories. Some of it goes to workers. Some of it goes to other firms (as non-labor costs). And some of it goes to the firm’s owners as profit.

Figure 2: Dividing a firm’s income stream. Accounting principles dictate that a firm’s sales get divided into profits and wages.

By definition, the terms on the left must sum to the terms on the right. So it’s not surprising that we find a correlation between wages and sales. They’re related by an accounting identity.

In comments on No, Productivity Does Not Explain Income (and on other sites), some economists pounced on this argument, saying it was fatally flawed. And in hindsight, I admit that I wasn’t clear enough about my reasoning. I was thinking about the real world. But the economists who critiqued my reasoning were thinking in terms of pure mathematics.

To frame the debate, let’s think about something more concrete than income. Let’s think about volume. In rough terms, the volume of an object is the product of its length, width and height:

V = L × W × H

Now, let’s pick a dimension — say length. Will the length of an object correlate with its volume? In general terms, no. I can make an object with any volume using any length. I just have to adjust the other dimensions appropriately. By doing so, I can make a cube have the same volume as a box that is long and thin.

So in pure mathematical terms, the accounting definition of volume doesn’t lead to a correlation between length and volume.

But when we look at real-world objects — like animals — we will find a correlation. If we took all the species on earth and plotted their length against their volume, we’d expect a tight correlation. A bacteria has a small length and a small volume. A blue whale has a big length and a big volume. Fill in the gaps between and we should get a nice tight line.

The reason for this correlation is that animals cannot take any shape. You’ll never find an animal that is a mile long and a few micrometers wide. Such a beast doesn’t exist. Yes, the shapes of animals vary. But in the grand scheme, this varation is small. As a first approximation, animals are roughly cubes. Or, if you’re a physicist, they’re spheres.

With this shape restriction, it follows from the definition of volume that animal length should correlate with animal volume. We’d be astonished if it didn’t.

So too with the correlation between sales per worker and wages. True, this correlation doesn’t follow purely from accounting principles. It follows jointly from accounting principles, and the fact that firms can’t take any form. We don’t find firms that pay their workers nothing. That’s slavery and its illegal. Similarly, we don’t find (many) firms that pay their workers the entirety of sales. That leaves no room for profit.

So in the real world, there are restrictions on how firms can divide their income stream. Here’s what these restrictions look like. In Figure 3, I’ve plotted the distribution of firms’ payroll as a portion of sales. This is the portion of sales that goes to workers. Across all firms, it’s a pretty tight distribution, clustered around 25%.

Figure 3: The distribution of firm payrolls as a fraction of sales. Data is for US firms in the Compustat database over the years 1950–2015.

Yes, it’s theoretically possible for a firm to give any portion of its sales to workers. But this isn’t what happens in reality. In the real world, most firms give between 10% and 50% of their sales to workers. Just like with the shape of animals, there are real-world restrictions on the ‘shape’ that firms can take.

Given these restrictions, it’s not surprising that we find a correlation between sales per worker and wages. When a firm’s income stream grows, so does the amount going to workers.

None of this has anything to do with productivity. It’s all about income. Sales are the firm’s income. And wages are the portion of this income given to workers.

Prices … the elephant in the room

Let’s conclude this foray into neoclassical thinking. The reason that sales don’t measure firm output is because they mix unit prices with unit quantities. Yes, sales per worker correlates with wages. But the elephant in the room is prices. Greater sales may be due to greater output. But it can also be due to greater unit prices.

In many cases, price differences are everything.

Imagine that a lawyer and a janitor both work 40 hours a week as self-employed contractors. The lawyer charges [/latex]1000 per hour, while the janitor charges [/latex]20. At the end of the week, the lawyer has 50 times the sales as the janitor. This difference comes down solely to price. The lawyer charges 50 times more for their hourly services than the janitor.

The question is why?

Neoclassical economists proclaim they have the answer. The lawyer, they say, produces 50 times the utility as the janitor. Ask economists how they know this, and they’ll answer with a straight face: “Prices revealed it.”

It’s time to recognize this sleight of hand for what it is: a farce. The reality is that we know virtually nothing about what causes prices. And we will continue to know nothing as long as researchers believe the neoclassical farce.

Further reading

The Aggregation Problem: Implications for Ecological and Biophysical Economics. BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality. 4(1), 1-15. SocArxiv Preprint.