Quantifying the meritocratic delusion

February 7, 2022

Originally published at pluralistic.net

Cory Doctorow

Our societal narratives are invisible by dint of their ubiquity, but they are far more important in stabilizing the status quo that all the cops and jails and domestic surveillance agencies put together.

Take inequality: when a few have much, and the many have little, the primary means of preventing the many from seizing the wealth of the few isn’t burglar alarms – it’s legitimacy.

If you can convince people that wealth is both earned and deserved, you can save a lot on armed guards, vaults and CCTV cameras.

The aristocracy once used the church to effect this legitimacy: as the English crown’s motto goes, “Dieu et mon droit” (“God and my right”).

The aristocratic legitimacy story makes it a literal sin to question inequality.

As the aristocracy gave way to merchant princes, society needed a new stabilizing story: the tale of the market, whose invisible hand allocates capital to the most deserving.

It’s a highly circular form of reasoning, of course: “I am deserving because I am rich; I am rich because I am deserving.”

Naturally, this self-serving logic attracted ridicule.

Notably, the sociologist Michael Young wrote a satirical, dystopian novel mocking this idea called “The Rise of the Meritocracy.”

His coinage, “Meritocracy,” was meant to deflate the delusion that wealth was merit and merit was wealth.

Instead, the term was adopted by the very people it was meant to lampoon: soon, capitalism boosters and defenders of inequality began to proclaim themselves to be “meritocrats” and defended the institutions that had enriched them as “meritocratic.” Yeah, it’s weird.

At its core, “meritocracy” is eugenics: the belief that some people are just intrinsically better than others (that’s why you often hear plutocrats boasting of their “good blood” – think of Trump here).

Sometimes it’s dressed up with coded language like “self-control” or “grit,” but ultimately, it’s about some in-born spark that both demands that the meritocrat lead the rest of us, and that they be rewarded for it. You can tell you deserves to rule because they are ruling.

As with all eugenics stories, meritocracy is trivially disprovable pseudoscientific nonsense.

Stipulate for the sake of argument that there are “meritocratic” traits that some of us are born with.

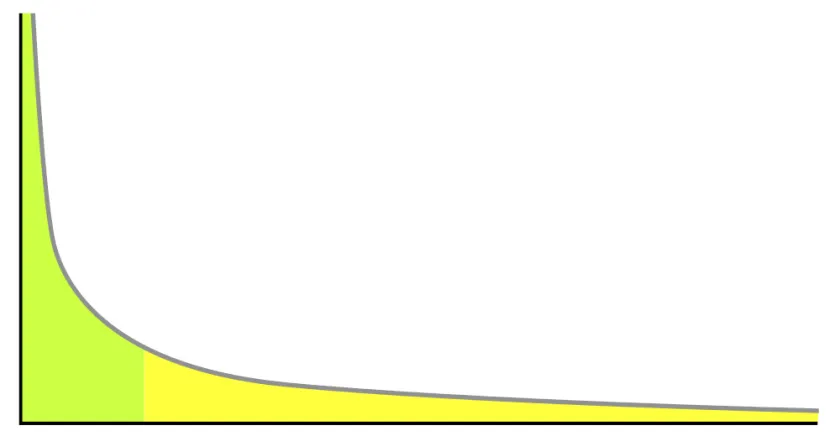

One thing we know about hereditable traits is that they follow a normal distribution – a bell curve. If merit is a heritable trait, then it should follow that same distribution.

But recall that “merit” is the excuse given for inequality: the market is a system for uncovering and rewarding merit, matching quanta of merit with dollars in a precise ratio (Bill Gates’s $114b and Jeff Bezos’s $196b tells us that Gates possesses 58% of Bezos’s merit).

And unfortunately for meritocracy’s coherence, the actual wealth distribution follows a power-law curve, not a bell-curve. The zottarich are an order of magnitude richer than the gigarich, who are an order of magnitude richer than the ultrarich and so on.

Plutocracy is asymptotic to infinity.

And while eugenics fails to account for this distribution there’s another hypothesis that turns out to be a good fit: the rich are lucky.

Enter “Talent vs Luck: the role of randomness in success and failure,” a paper from a group of U Catatania researchers that proposes a model for explaining deepening inequality.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.07068

A breakdown in MIT Technology Review explains it well. The model assumes that N people have various talents “around some average level, with some standard deviation.”

“The computer model charts each individual through a working life of 40 years. During this time, the individuals experience lucky events that they can exploit to increase their wealth if they are talented enough.

“However, they also experience unlucky events that reduce their wealth. These events occur at random.”

After 40 simulated years, the agents in the simulation have a wealth distribution that looks a hell of a lot like ours.

They run the simulation repeatedly, and get the same distribution every time. In other words, markets allocate capital primarily by luck, not merit.

However, I’d like to see another version of this experiment that adds in immorality: a willingness to cheat and steal. Given the state of the plutocracy, I hypothesize an even stronger correlation.