Do we believe that the average Chinese adult is “wealthier” than the average European?

October 24, 2022

Originally published at Fresh Economic Thinking

Cameron Murray

Do you believe this headline? I don’t.

The many problems with measuring a country’s wealth are on full display in this Credit Suisse report.

But let’s start a little closer to home.

When I married my wife I promised to look after her financial and material needs. That promise has a market value. I could have issued a “marriage bond” and sold it into the market in order to capture that capital value.

Marriages have in reality worked this way for a long time. Dowries are still common in many places. That’s a reflection of the market value of the promise. Just like any other asset.

The Capital as Power (CasP) approach to economics calls the way we come up with values of future promises the capitalisation ritual. Our rituals, or conventions, mean that the value of some promises gets capitalised and traded, and other promises don’t.

JW Mason makes the case that this helps resolve the puzzle of low German wealth that is consistently found in wealth surveys like the Credit Suisse report.

For example, imagine two otherwise similar countries, one of which makes provision for retirement income through a pay-as-you-go public pension system, and the other of which uses some form of funded pension. The two countries may have identical levels of output and income, and retirees may receive exactly the same payments in both. But because the assets held by the pension funds show up on balance sheets while the right to future public pension payments does not, the first country will have less wealth than the second one. Again, this does not imply any difference in production, or income, or who ultimately bears the cost of supporting retirees; it is simply a question of how much of those future payments are capitalized into assets.

The Credit Suisse report explicitly says (p19) that

Private pension fund assets are included, but not entitlements to state pensions.

They also note why countries with similar income levels can have widely varying wealth estimates.

Part of the explanation is that more generous social benefits, including pensions and health care, make personal saving less pressing than elsewhere.

But we could estimate the market value of future public pensions by issuing a financial instrument called a “pension bond” that entitles the recipient to the public pension of a country. A market price can be found by selling a few of these bonds on global markets. We can then multiply that price by the number of people in the country and get a capitalised value.

Alternatively, we can capitalise the current flows of payments in the pension system. Take my country of Australia. Our public pension system pays $55 billion per year in income to retirees. At a 4% capitalisation rate, we get a market value of those promises of about $1.4 trillion, or $140,000 per household. The value would be much higher if we factored in some future growth.

I suspect that capitalising the value of public pensions would make the Europeans seem very wealthy all of a sudden. Trillions of dollars of wealth would appear from nowhere. But instead, we ritually ignore this, and in doing so, devalue uncapitalised promises in our political debates.

Another problem in wealth measurement concerns housing asset values. A regulatory regime that keeps rents low will also reduce house prices. This will show up as lower measured wealth in terms of the capital value of things that are ritually capitalised, in this case, residential property.

A fall in housing asset values due to a decline in rents really does reduce the wealth of property owners. But it also increases the value of future surpluses for renter households. Because the increased value to renters of a promise to keep rents low is not capitalised, it is ignored.

But we know that keeping rents low has a value to renters that can be capitalised. The case of Herbert Sukenik being paid $17 million to leave his rent-controlled apartment in New York so that it could be redeveloped shows this clearly. To get him to move out, a price was negotiated that reflected the market value of his ongoing discounted rent.

This is a case where our rituals required that the market value of low rent be capitalised in order to pay upfront the full future value and make a trade of promises. Now imagine how big the capitalised value of low rents would be in a country like Germany where more than half of households rent and strong regulations keep rents low.

The flip side to these two wealth measurement issues happens in Australia. We have $3 trillion in assets in privately held superannuation pension funds and a fairly deregulated private rental market and a tiny public housing sector. Alongside this, housing assets are being capitalised at declining cap rates, boosting market values by trillions in the past few years.

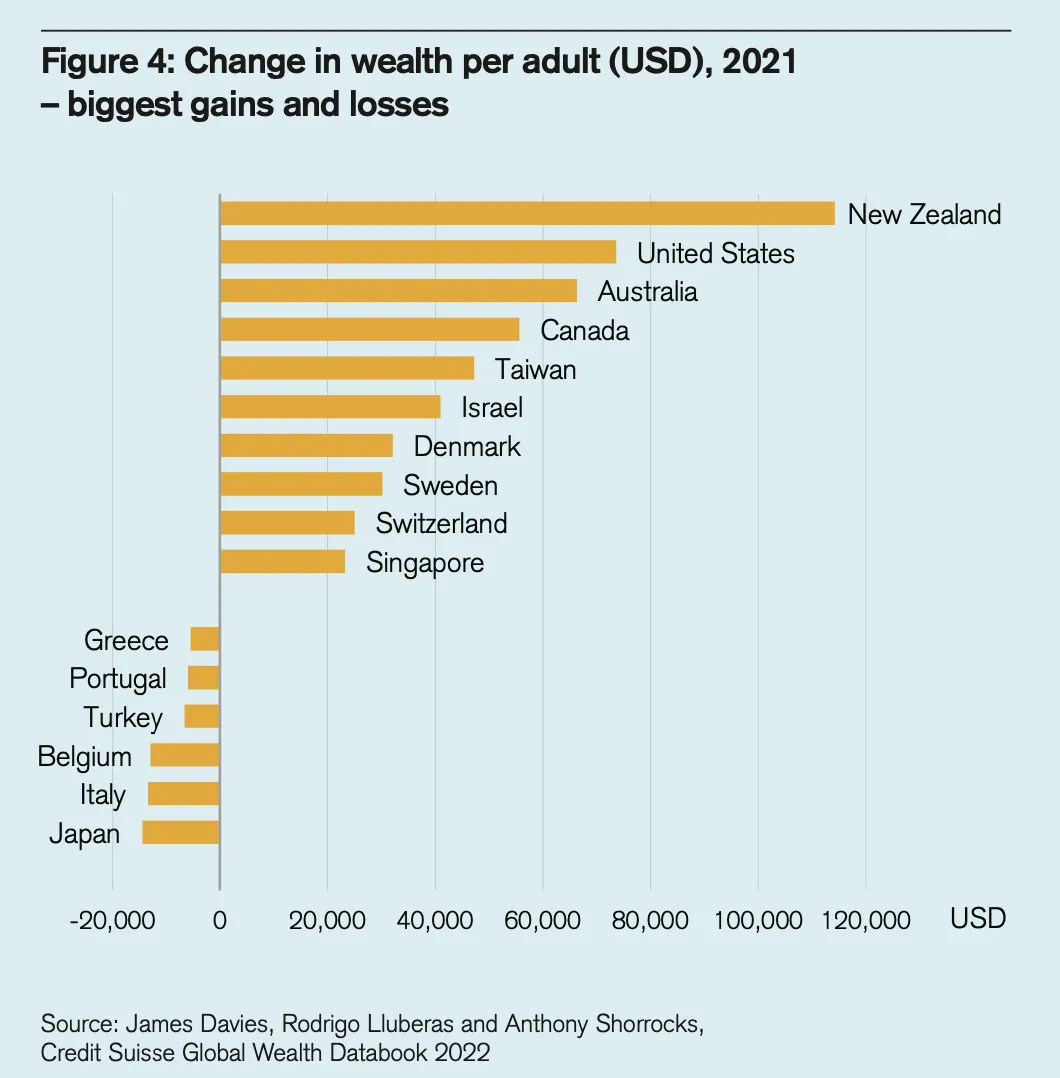

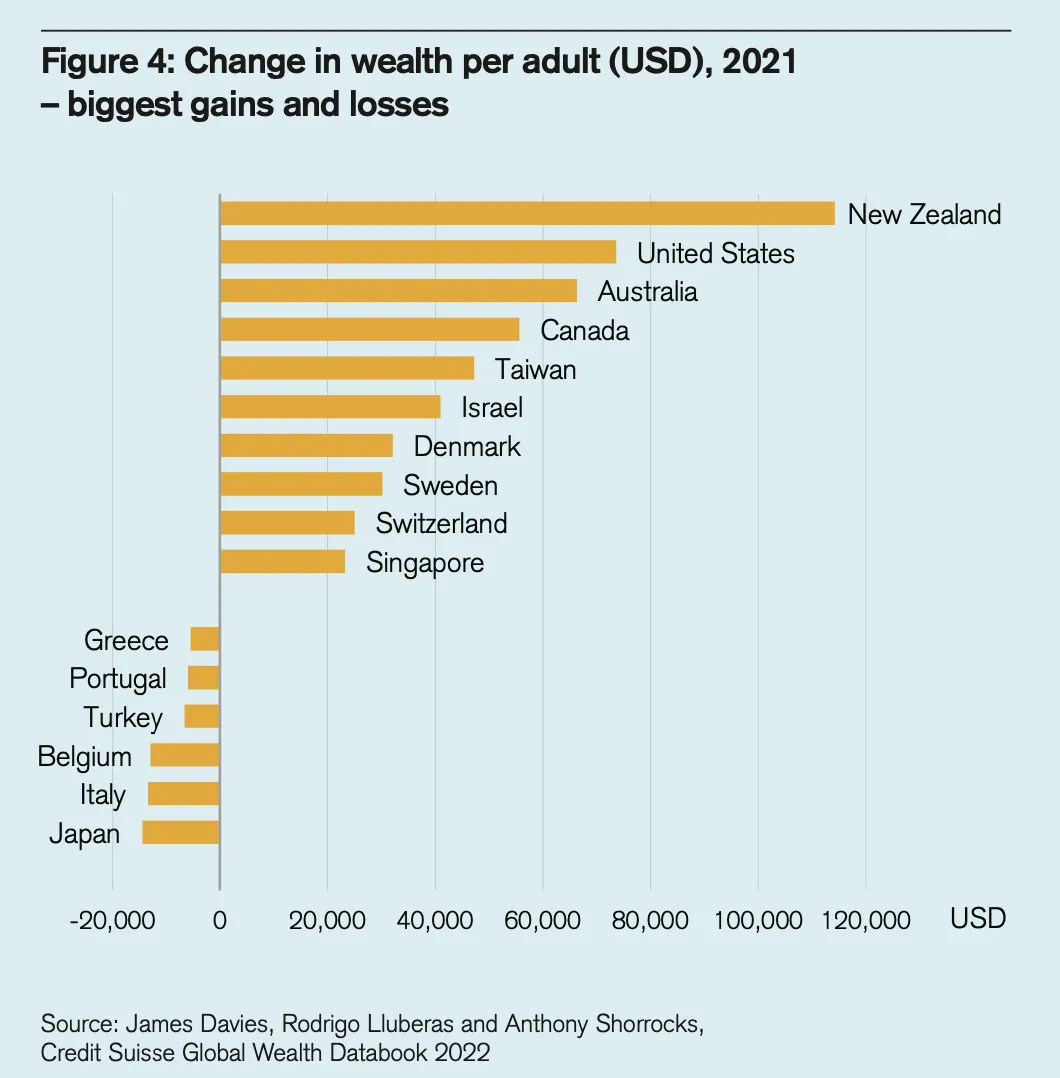

The Credit Suisse report notes that the 25% price gains for New Zealand housing, and the 31% gains in Australia, was a major determinant of the recent growth in their measured wealth.

But does that make us wealthier? I’m not so sure about that. And I’m also not so sure about the value to our economic and political debates of measuring wealth by the value of only the things that we ritually capitalise.

I talked about this in a recent FET podcast episode. Enjoy.