Alberta’s Rockefeller Coups, Part 3: Who Would Do This To Themselves?

December 13, 2022

Regan Boychuk

Author’s note: At the end of the First Cold War, Canada tried to make the polluter pay. This resulted in the United States launching an unknown, but successful coup in Alberta over the course of 1991-92. And the results of that coup are the single biggest threat to a liveable future.

This three-part series will document the secret January 17th 1991 ‘no-lookback’ deal over oilfield cleanup, the December 5th 1992 selection of Ralph Klein as the leader of Alberta’s governing party, and the April 9th 2003 US recognition of Alberta’s oilsands as “bankable” reserves.

Who Would Do This To Themselves?

Two men have been supreme in creating the modern world: Rockefeller and Bismarck. One in economics, the other in politics, refuted the liberal dream of universal happiness through individual competition, substituting monopoly and the corporate state, or at least movements towards them.1

— Bertrand Russell 1934

Ernest Manning’s father left a wealthy British market town where an Anglo-Saxon king and a French Tudor queen are entombed to become a farm labourer in Manitoba. Ernest’s mother stayed behind to ‘continue working as a live-in lady’s maid at a stately home near Piccadilly Circus in London’ until George Manning established the family’s first homestead in eastern Saskatchewan.2

Only occasionally attending Methodist church as a child, Manning considered himself a nominal Christian at best. But a 14-year-old Ernest mail-ordered a $1,750 (in 2022$) 30-ft radio tower, apparently because he liked to read Popular Mechanics and the Sear’s catalogue. It took Ernie another few months to scratch together the customs duty on his big investment from Chicago, but ‘the fire-and-brimstone radio broadcasts from a forty-seven-year-old Calgary high-school principal and self-taught Bible scholar’ it beamed in are supposed to have changed Ernie’s life. Barely two years after taking delivery of his radio tower, a 17-year old Ernest bought a suit from the Sear’s catalogue again, took the train to Calgary to meet ‘Bible Bill’ Aberhart, and returned to Saskatchewan to listen to Aberhart crowd-source $1.1 million (in 2022$) over the spring and summer of 1927 to build a bible college in Calgary. Ernest Manning would be its first student that fall, taken in as the son-they-never-had by the Aberhart family the following year, would be the school’s first graduate, and soon after Aberhart’s “Echo” on the radio as the Great Depression set in.3

Manning would disown the Aberhart family just as he had the family he left behind in Saskatchewan, but not before guiding Aberhart to adopt the ill-fitting political philosophy of social credit (which Ernest Manning’s son Preston derides as a mixture of “pre-Keynesian economics, social resentment, and untutored hope”) and riding political discontent and scandalous accusations during the Great Depression into provincial government on August 22nd 1935. At 26, Ernest Manning was the youngest cabinet minister in the British Empire, and when Aberhart died in 1943, Manning succeeded him as premier until retiring after 33 years in legislature in 1968. Ernest Manning’s first order of business in 1935 and throughout was to entice outside capital to invest in Alberta oil, but his sly creation of Savings & Loan-style “state credit houses” would also prove to be of great consequence in 2003.4

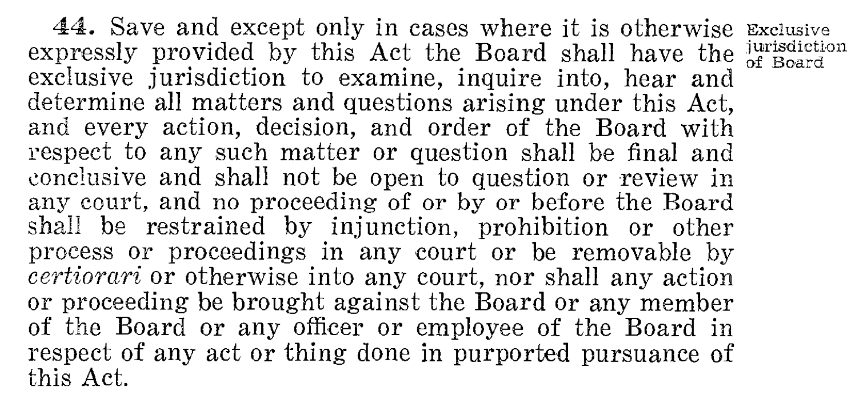

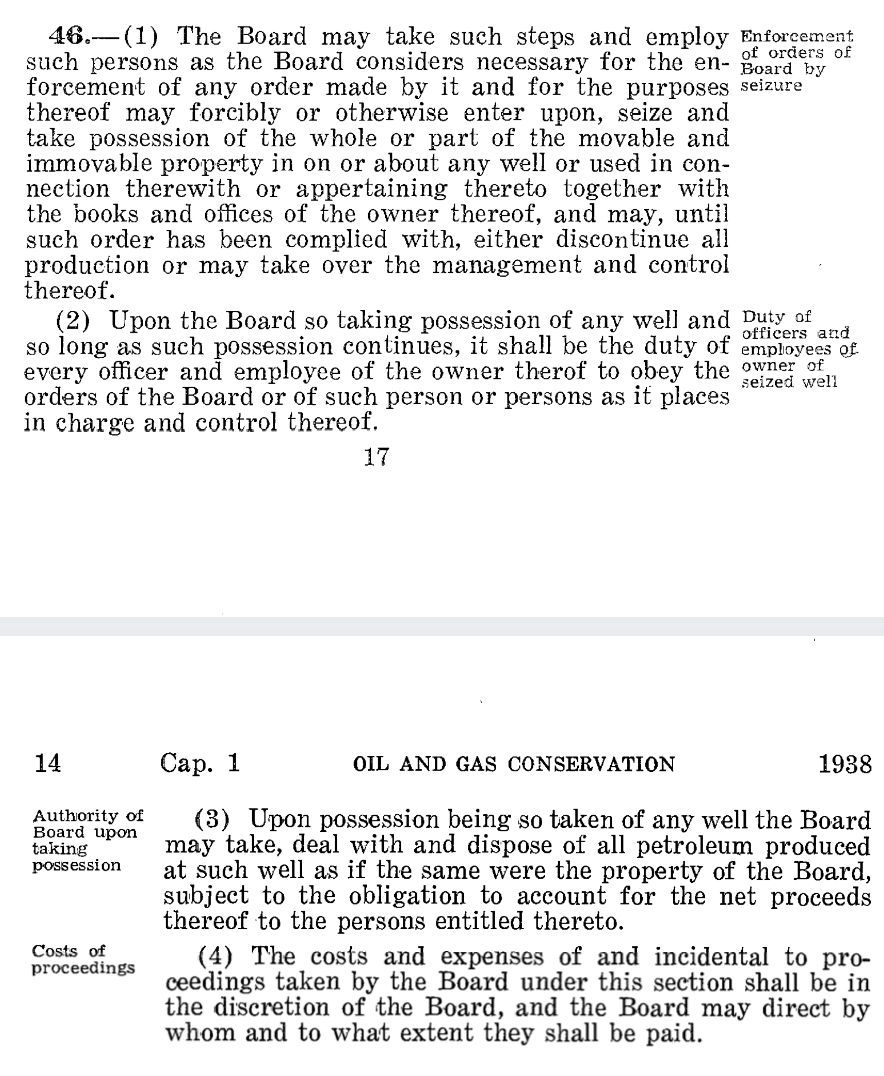

On November 22nd 1938, Manning established Alberta’s new oil and gas regulator as above the law and the province ceased to be a democracy. Oil wore an American crown here and Manning bowed to it. In 1936, Alberta had become ‘Canada’s first, and only, province to default on a principle debt payment.’ What’s more, ‘Alberta’s provincial government was committed to thwarting the claims of finance capital.’ Manning had tapped the US-born Nathan Tanner as energy minister, who cabled Washington, DC asking for recommendations from the US Department of the Interior. The head of Alberta’s first real regulator was American William Knode from the Texas Railroad Commission. After a special session of the legislature, the new Oil and Gas Resources Conservation Act was revised to give the regulator ‘remarkably wide-ranging authority’, ‘not obliged to hold hearings or to give reasons for its decisions.’5

Shortly afterwards, Manning, Aberhart, Tanner, and Knode spent an unexplained month in Britain. The pretense was raising money for investment in Alberta oil, but with Alberta still in default to international creditors and war clouds looming over Europe, there was no hope of raising British capital. Instead, in hindsight, the trip to London looks like the transfer of Alberta (and Palestine? Australia?) from the royal British empire to the Rockefellers’ private empire. A new British Colonial secretary was appointed briefly on November 22nd 1942, who asked the Canadian government whether it endorsed the idea of ‘Parent States’ after WWII. The Canadian government did endorse the idea – small wonder that Prime Minister Mackenzie King received a $1.3 million dollar gift from his best-friend-for-decades, John D. Rockefeller Jr., upon his retirement. Having exchanged secret messages for decades, the Rockefeller Foundation also gave $1.3 million to arrange Mackenzie Kings papers for publication.6

The first acts of Manning’s new regulator slashed Alberta oil production by more than 60% in the fall of 1938, prompting a Royal Commission and that special session of the legislature. The chief justice of Alberta’s Supreme Court, Alexander McGillivray, led the commission. Justice McGillivray’s sage advice fell on deaf ears and McGillivray died of a heart attack at the age of 56 the year his report was published by Imperial Oil in Calgary. The first American head of the Alberta regulator had returned to Washington after his trip to London, leaving the position empty for more than a year. American Robert Allen eventually replaced Knode, but also left abruptly in the summer of 1941, this time ‘to advise the US government on growing oil supply and distribution problems’. ‘At first, it was considered that Allen was on loan to the US government, but it soon became apparent that he would not be returning to Alberta [either].’7

In hindsight, the August 1941 Atlantic Conference between the US and UK (signed amid great secrecy off the coast of Newfoundland) also takes on new significance. Roosevelt’s soft support for eventual decolonization was being outmaneuvered by the Rockefeller faction of US politics, and inviting both the president’s sons to the secret Canadian flotilla is likely to have given others a chance to solidify the transfer of Alberta (and Palestine? Australia?) from UK to US monarchs. Just before the Rockefellers first foisted ‘conservation’ on the US state through the President’s Federal Oil Conservation Board in December 1924, the oil industry warned New York Times readers against any increase in drilling activities. Cities Service head Henry Doherty said, “If we do not get our house in order sooner or later some one else will attempt to do it with a stick of dynamite or an axe.” It was just before the Atlantic Charter secured the unique ‘special relationship’ between the US and the UK that Alberta’s first commercial bitumen production began. It was shortly after the Atlantic Charter that Abasand Oils was destroyed by fire. In case anyone thought that was an accident, it burned down again very shortly after Abasand had been rebuilt with federal money to help meet wartime demand. The second fire convinced Ottawa to retreat from 30 years of research, leaving bitumen development to Manning.8

By April 1943, Aberhart was too worn out to perform his duties as Alberta premier. Diagnosed with liver cirrhosis usually associated with alcohol abuse, no one ever implied Aberhart had a drinking problem. (At this same moment, across the Atlantic, a British colonial official remarked without elaborating about how the US notion of ‘independence’ was nominal at best. “The Americans are quite ready to make their dependencies politically ‘independent’ while economically bound hand and foot to them and see no inconsistency in this.”) A month later, Premier Aberhart’s liver failed, he slipped into a coma, and he died before Manning had arrived by train. It was only after Aberhart’s death that creditors would meet with the Alberta government. The plan to exit bankruptcy evolved in an unusual way: ‘Clearly this was a plan that had the involvement and backing of the Dominion Government, the Bank of Canada, and representatives of domestic and foreign bondholders and knowledge of its existence limited to only a few key players in the Alberta government.’9

And in case there were any doubts left about lightening striking Abasand twice or if Alberta’s chief justice had died of natural causes in 1940, the first real Albertan in charge of the oil and gas regulator died of a heart attack just four days after signing a very smart deal with Imperial Oil nemesis Shell, who’d discovered Alberta’s biggest gas field at Jumping Pound in 1944 and by 1945 was ready to develop the field cooperatively as a single unit – the supposed industry ideal. Like Rockefeller Sr’s early opposition to the pipe line, Dr. Edward Boomer’s October 1945 ‘heart attack’ suggests there is something more than efficiency driving the Rockefeller machine.10

With the chief justice knocked off, the premier dead, the war with bankers over, the feds scared off, an uppity local regulator put 6ft under, and WWII ending with rapidly growing demand for petroleum, Alberta was finally ready to be incorporated into the global supply system coordinated by ‘the Seven Sisters cartel’, as Enrico Mattei coined Big Oil. Alberta’s first big oil gusher, February 1947’s Leduc #1 was carefully planned, blowing-in to a crowd of hundreds. A ‘surplus’ WWII refinery in Alaska was purchased from the Pentagon for a song, dismantled, and trucked to Edmonton for the Leduc field, with a pipeline to Imperial Oil’s Ontario refineries also following before long. (Manning’s energy minister Tanner exited politics through the revolving door in 1952 ‘to make his fortune in oil and gas, notably as the first president of Trans-Canada Pipelines; [in 1979, he was] a senior Elder in the Mormon Church hierarchy in Salt Lake City, Utah …’)11

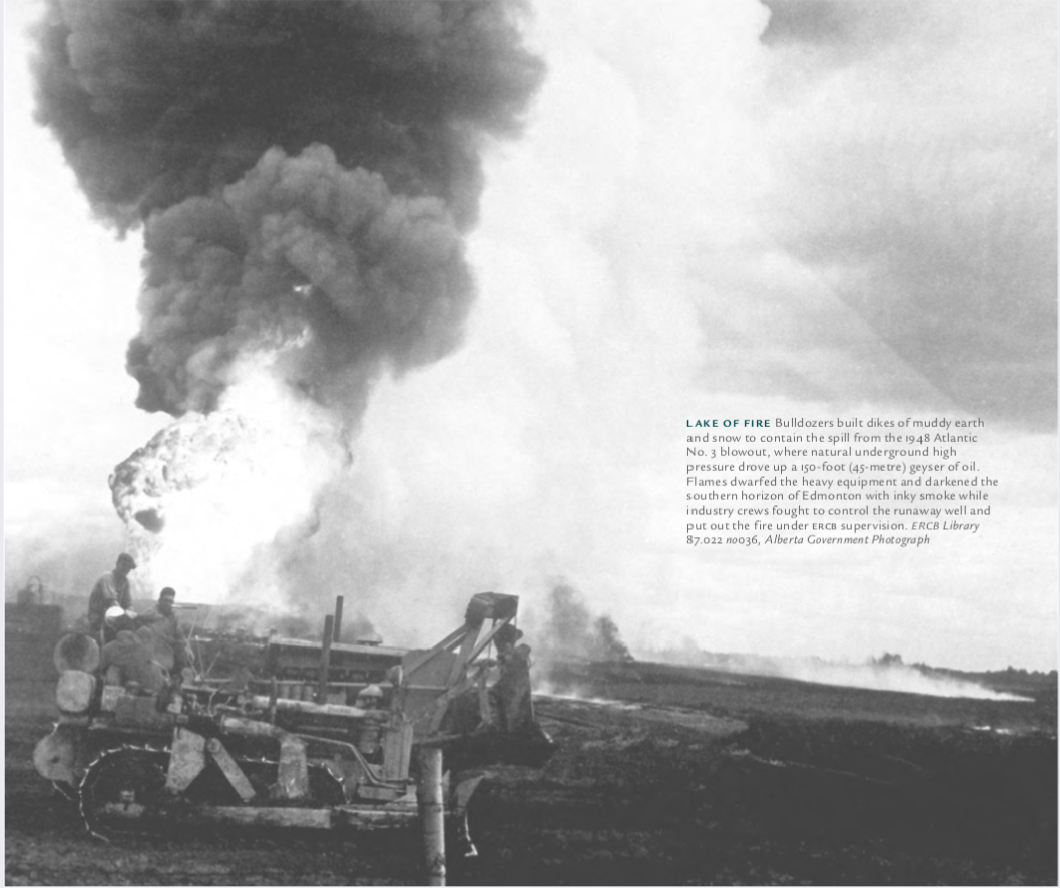

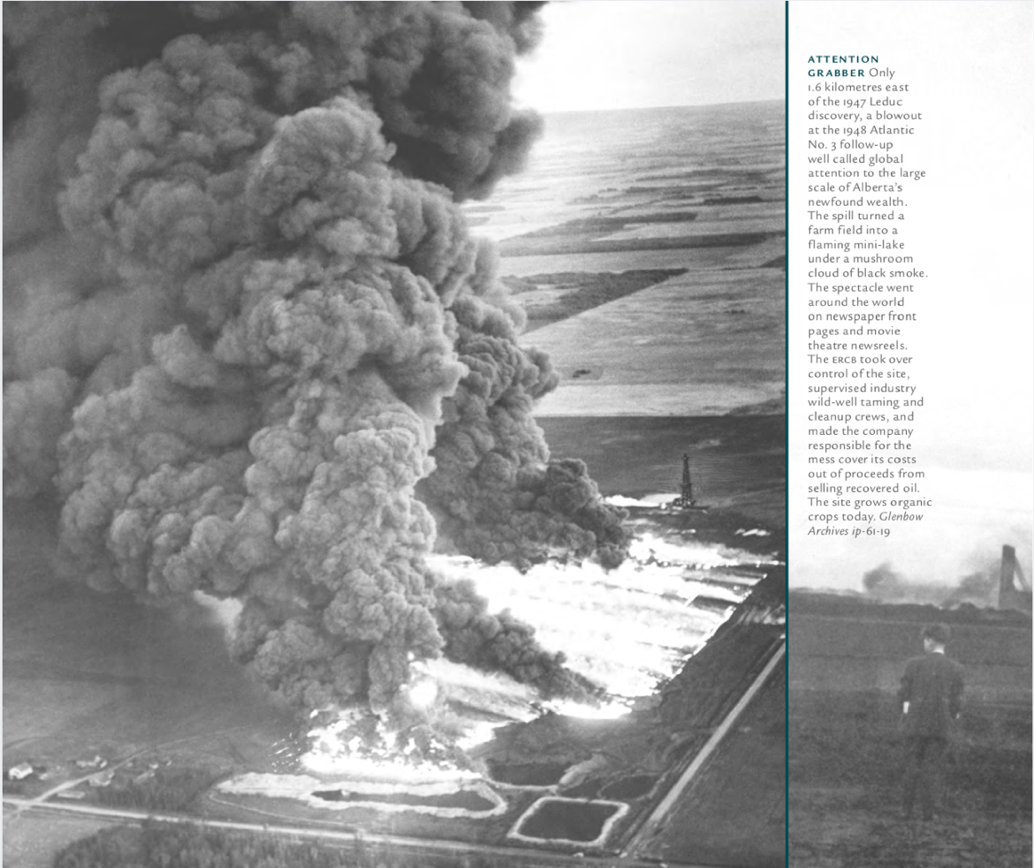

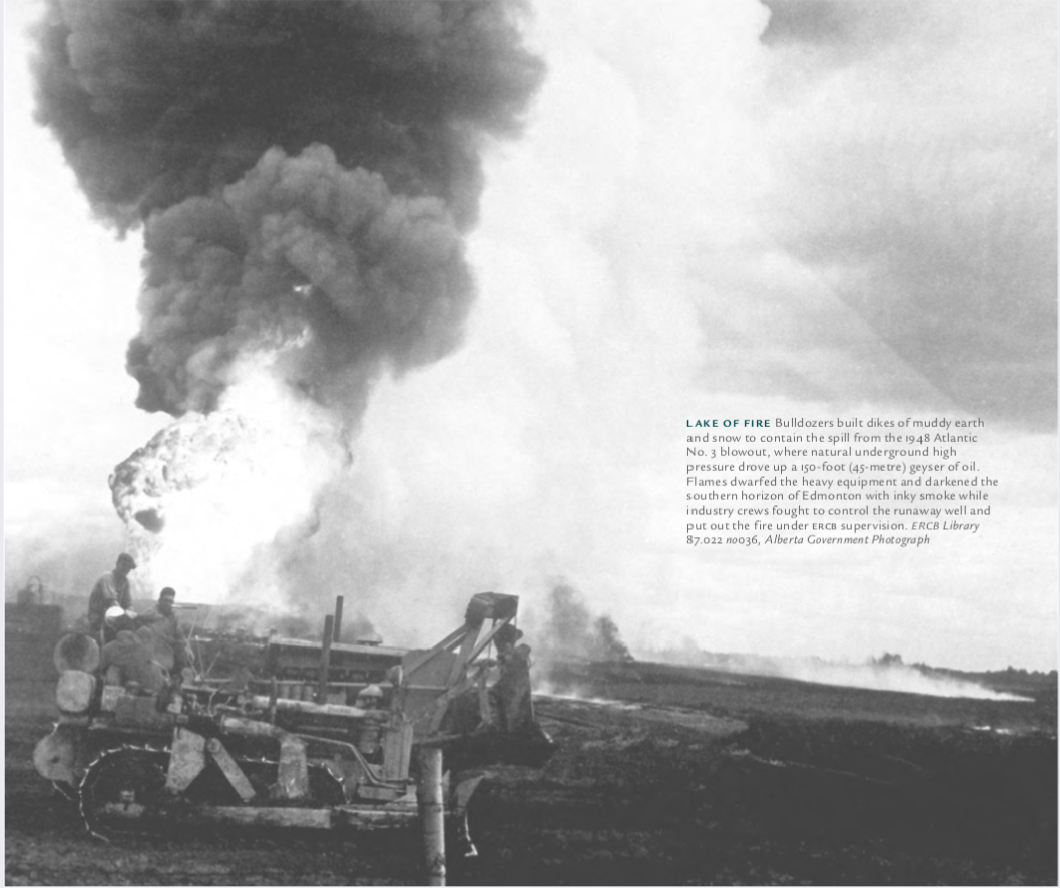

In early 1948, Manning was not yet in complete control or did not prevent the populist impulses of his Social Credit party implementing a royalty bonus program that saw Imperial getting outbid for parcels by independents willing to give the province 50% or more in extra royalties. Within days of the second sale under the new royalty bonus program, the Atlantic #3 well in Imperial’s field blew out for six months – through an entire provincial election campaign – until royalties were legislatively capped at 16.67% and the royalty bonus program was not just cancelled, but the second sale was redone under new cap. In case anyone on earth didn’t get the message, just as the first relief well began pumping water to finally snuff out the Atlantic #3 blowout, it caught fire, burning apocalyptically for almost a week. It remains Canada’s largest onshore oil spill, but is missing from the Alberta Energy Regulator’s spill database. The environmental terrorism of Atlantic #3 also settled the question of liability for such ‘accidents’: settled out of court, the driller (who’s name still graces Calgary’s professional football stadium) merely had to pay for the cleanup with revenue from oil recovered from the spill. The Atlantic #3 crisis also marked the moment when Manning asserted dictatorial control of the Social Credit party that had been led by Aberhart.12

Figure: A blowout at Atlantic #3 in 1948.

Figure: A blowout at Atlantic #3 in 1948.

The Manning’s Rockefeller dictatorship in Alberta culminated in the scheme unveiled as a fait accompli on the 1959 anniversary of Leduc #1 (and the British retreat from Palestine): a nuclear blast in Fort McMurray to double the world’s oil reserves in an instant. The insane scheme was approved at every level of the provincial, federal, and US governments. There were no hearings or environmental studies, the oversight committee was toothless by design. The Rockefellers were only denied the status of the world’s first trillionaires by Canadian Prime Minister Diefenbaker, who used the anti-nuclear movement as the excuse for protecting Alberta and everyone else. Under President Kennedy, the Rockefellers coup’d Diefenbaker in 1963 to pave the way for the Vietnam-assisting-war-criminal, Canadian prime minister Lester Pearson.13

When US imperial state planners spoke of oil reserves on a scale to “constitute a stupendous source of strategic power, and one of the greatest material prizes in world history”, they refer to Saudi Arabia, but they mean Alberta.14 The US in Saudi Arabia enjoyed nowhere near the control the Rockefellers had over Alberta reserves and profits + rents. There is a perfectly Alberta-shaped hole in the history of the planning for post-WWII. Because Alberta was already in the back pocket of the architects of that New World Order.

Pre-war imperial arrogance lived on in the new hegemon. When the Rockefellers launched the career of the ever-loyal future secretary of state Henry Kissinger in 1958, advisor to a half-dozen presidents and Kissinger’s guide at Harvard, prof. William Elliot called for more “good colonialism” selling “colonial peoples” on the idea their resources are a “trust for the world”: “tribal chieftains … claim[ing] absolute power over resources … is evidently absurd”. Energy regulation has been profoundly corrupted by capture since inception, but it reached its zenith in Alberta. From November 1938 until August 1971, the regulator was explicitly above the law. Alberta’s democratic interlude, 1971-1991, threatened all that. Naturally, Rockefeller academics and economists responded. University of Chicago economists George Stigler and Richard Posner invented the strawman of ‘public regulation theory’ out of whole cloth, publishing in a virtually-in-house journal a few months before the end of the gold standard.15

The Rockefellers’ grand scheme of financializing entire oilfields had been thwarted in 1959, but the August 1971 end of the international gold standard presented another opportunity. Lucky for everyone else, the election of Peter Lougheed as premier of Alberta two weeks later robbed the Rockefellers of control of a provincial savings & loan to begin mortgaging entire oil fields. The Rockefellers had to settle for using American S&Ls centered around more piecemeal US oil reserves in California and Texas, crimes that landed a thousand banking executives in prison (back when there was such a thing as regulation). As the documentary series The Con details, one of the S&L scammers stayed out of jail to found the sub-prime mortgage industry in the 1990s.16 There is a direct connection between the occupation of Iraq and the sub-prime mortgage predation that soon after ravaged America: It was all part of the Rockefellers’ ultimate scheme being realized in Alberta.

As late as 2003, Alberta’s proven bitumen reserves still stood at only 3 billion barrels. The day US Marines pulled down that statue in Baghdad, the US Energy Secretary informed Alberta it now had an extra 175 billion barrels of proven oil reserves in Fort McMurray. Six months later, the recommendations of a 1998 Alberta oil & gas taskforce became National Instrument 51-101: Standards of Disclosure for Oil and Gas Activities in September 2003. NI 51-101 is a hoax that allows reserves to be used as legal collateral by licensees, regardless of cleanup costs, ability to develop, or profitability. In less than a year, the FBI was reporting an epidemic of mortgage fraud by lenders. The Con also details the mortgage foreclosure fraud that cheated tens of millions of Americans, and at that same moment, the Rockefellers pulled the trigger on a little-known (to put it mildly) clause of the 1913 Federal Reserve Act that allowed them to take the final step to domestic monarchy: The illegal use of FRA 13(3) in 2009 took the Rockefellers from printing new money using other peoples’ oil as collateral to simply printing $29 trillion straight from the US Federal Reserve and handing it to Wall Street.17 These are the main sources of global financial instability/imbalance and the seemingly endless supply of bad loans for oil & gas & bitumen Ponzi’s in North America.

Two weeks before the infamous April 1914 Ludlow Massacre ushered in the ferocious first wave of reaction against burgeoning political democracy, John D. Rockefeller Jr. appeared before a congressional investigating committee defending his opposition to collective bargaining. Asked by the committee chairman if he would maintain his opposition “if it costs all your property and kills all your employees?” Rockefeller answered, “It is a great principle.” The same logic remains at the heart of the Rockefellers private empire through today. Canada’s longest-serving prime minister was Rockefeller Jr’s BFF, but was aghast at the scale of wealth being transferred into private hands. Mackenzie King wanted better for Canada, but his compromises with the Rockefellers betrayed those aspirations. What Mackenzie King confided in his diary as he toured the Colorado coal fields on behalf of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1915 has not yet come to pass, but still could at any moment:

The only defense there can be for private ownership in natural resources is the corruption incident to government ownership and the check which would be placed on development if the possibility of reaping large fortunes did not exist as an inducement for the investment of private savings. Were men honest and actuated by a sense of duty in their personal relations, private ownership in natural resources would not last for a day. It is because men know that human nature is as weak as it is that they feel obliged to penalize themselves by permitting a sort of natural selection in the matter of cupidity and daring to determine who are to be the controllers and possessors of great wealth as against its real owners, the people as a whole.18

But there is more than hope. As dark as the above truths are, there also happens to be nearly certain to be another chance for democracy in Alberta soon. The world’s greatest crime is set to cure itself next spring, if only Canadians are able to keep Alberta’s New Democratic Party leadership safe to pursue the province’s interests at the expense of the Rockefellers.

In the course of preparing for the greatest crime in history, the Rockefellers blessed Alberta with our own (almost) bank: ATB Financial. As Lenin advised not long after Ludlow:

Capitalism has created an accounting apparatus in the shape of the banks, syndicates, postal service, consumers’ societies, and office employees’ unions. Without big banks socialism would be impossible. The big banks are the ‘state apparatus’ which we need to bring about socialism, and which we take ready-made from capitalism; our task here is merely to lop off what capitalistically mutilates this excellent apparatus, to make it even bigger, even more democratic, even more comprehensive. Quantity will be transformed into quality. A single State Bank, the biggest of the big, with branches in every rural district, in every factory, will constitute as much as nine-tenths of the socialist apparatus. This will be country wide book-keeping, country-wide accounting of the production and distribution of goods, this will be, so to speak, something in the nature of the skeleton of socialist society. We can ‘lay hold of’ and ‘set in motion’ this ‘state apparatus’ (which is not fully a state apparatus under capitalism, but which will be so with us, under socialism) at one stroke, by a single decree, because the actual work of book-keeping, control, registering, accounting and counting is performed by employees, the majority of whom themselves lead a proletarian or semi-proletarian existence.19

Ernest Manning faked social credit (along with everything else) to get elected during the Great Depression, but there is a genuine and extremely pertinent thread of logic to public banking and debt jubilees in an age of financial and climate crisis. Ernest Manning’s political opponents brought the British founder of Social Credit to Alberta to assess the situation in 1937, where a Social Credit government was failing to live up to its name. His advice remains tantalizing in its potential. Our greatest obstacles remain our own imaginations:

I do not suggest that the financial interests in their turn have not the power to inflict damage upon Alberta but I do not believe that that power, if seriously challenged, is anything so great as it is popularly supposed to be. Nor do I think that the condition of affairs in Alberta would be very much worse, except possibly for a very short time, if such ill-advised action upon the part of the financial authorities were put to the test. The financial system is essentially a system of black magic and one of the best protections against black magic is not to believe in it.20

Notes

-

Russell 1934 p. 357

Russell 1934 Bertrand Russell Freedom and Organization, 1814-1914 [1934] New York: Routledge 2001↩︎

-

E Hyde 1946 p. 521 (US foreign policy on oil reserves); Encyclopaedia Britannica Bury St. Edmunds; Magna Carta 2014; Russell 1934 pp. 357-59 & Handlin 1955 (Rockefeller Sr’s character); Taylor 2019 pp.12-13, 51-52 (Imperial takeover by Rockefellers); Spaulding 1993 pp. 68-71 (early Rockefeller spending in Canada); Patnaik & Patnaik 2021 pp. 113-20, 126-27 (imperialism: ‘appropriating surplus without any quid pro quo’)

Hyde 1946 Charles Cheney Hyde “Protection by the United States of American-owned property in war-stricken areas” Columbia Law Review v46#4 (July 1946): 519-32

p. 521: “‘In the early twenties the United States Government strongly urged that American oil interests expand abroad and develop adequate reserves …With the strong diplomatic backing of their government, American operators embarked on exploratory efforts in many parts of the world.’ The interest of the United States in the matter was revealed by Mr. Kellogg, Secretary of State, in a communication to the Secretary of the Navy, June 29, 1928, when he said:

“The Department of State in connection with rendering assistance and support to American companies seeking or operating petroleum concessions abroad, is constantly seeking the recognition and practical application by foreign governments of the policy of the open door and equality of commercial opportunity. It is obvious that such a policy can be followed only as long as the United States accords to nationals of foreign countries treatment similar to that sought by this Government for its nationals abroad. …

“In view of the extent of our probable future dependence upon foreign reserves of petroleum, the importance of keeping the Government of the United States in a position consistently to support and assist American interests will, I am sure, be appreciated. Accordingly, I consider it important that no action be taken in the United States discriminating against foreign interests as such in the oil industry.””

Encyclopaedia Britannica “Bury St. Edmunds” in Encyclopaedia Britannica: A dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information [1768-71] 11th edn (New York: Cambridge University 1910): 868

p. 868: “BURY ST EDMUNDS, a market town … 87 m. N.E. by N. from London by the Great Eastern railway. Pop. (1901)16,255. It is pleasantly situated on a gentle eminence, in a fertile and richly cultivated district. The tower or church-gate, one of the finest specimens of early Norman architecture in England. … St Mary’s church … was erected in the earlier part of the 15th century, and contains the tomb of Mary Tudor, queen of Louis XII of France. … All these splendid structures, fronting one of the main streets in succession, form, even without the abbey church, a remarkable memorial of the wealth of the foundation. …

… Bury St Edmunds (Beodricesworth, St Edmund’s Bury) … was one of the royal towns of the Saxons. Sigebert, king of the East Angles, founded a monastery here about 633, which in 903 became the burial place of King Edmund, who was slain by the Danes about 870, and owed most of its early celebrity to the reputed miracles performed at the shrine of the martyr king. … There was formerly a large woollen trade.”

Magna Carta 2014 “History of the Magna Carta: 800 years of liberty: Bury St. Edmunds” Magna Carta Trust (2014)

“Bury St Edmunds has a pivotal role in the history of Magna Carta. One chronicler relates that in 1214 a group of Barons met in St. Edmunds Abbey Church and swore an oath to compel King John to accept The Charter of Liberties, a proclamation of Henry I. It was the direct precursor to Magna Carta a year later.”

Russell 1934 Bertrand Russell Freedom and Organization, 1814-1914 [1934] New York: Routledge 2001

pp. 357-59: “[John D. Rockefller Sr’s] father kept his occupation a secret: he was, in fact, an itinerant pill-doctor. …”Dr. William A. Rockefeller, the Celebrated Cancer Specialist” … was often in trouble with the police, and on one occasion the farm was sold for debt; owing to his escapades, the family had to make frequent moves. He was very proud of his shrewdness, and would boast of his skill in outwitting people. “He trained me in practical ways,” said his son John. “He was engaged in different enterprises and he used to tell me about these things and he taught me the principles and methods of business.” The father’s own description of his teaching the “principles” of business is simpler: “I cheat my boys every chance I get. I want to make ’em sharp. I trade with the boys and skin ’em every time I can. I want to make ’em sharp.”

… Poverty, frequent moves, his mother’s unhappiness, and the neighbours’ hostility must have made a deep impression upon him as a child. Although he could be bold in business, he always feared the crowd, and sought secrecy instinctively, even when it served no purpose. The timid man who wants power is a very definite type. Louis XI, Charles V, and Philip II are instances: pious, cunning, unscrupulous, industrious, and retiring. But power, for Rockefeller, could only be obtained through money.”

Handlin 1955 Oscar Handlin “Capitalism, power, and the historians: An essay review” New England Quarterly v28#1 (March 1955): 99-107

pp. 99-102: ” Capitalism and the Historians. By T. S. Ashton, Louis Hacker, F. A. Hayek, W. H. Hutt, and Bertrand de Jouvenal. Edited with an Introduction by F. A. Hayek. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1954. Pp. viii, 188. $3.00.)

Study in Power. John D. Rockefeller Industrialist and Philanthropist. By Allan Nevins. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1953. 2 vols. Pp. xviii, 441, xii, 501. $10.00.)

The volume of essays edited by Professor Hayek is a disgraceful performance. That occasional grains of truth are scattered through it does not diminish the essentially misleading character of the whole. The thesis of the book is clearly set forth by the editor. “A socialist interpretation of history … has governed political thinking for the last two or three generations.” Essential to that interpretation was “the legend of the deterioration of the position of the working classes in consequence of the rise of ‘capitalism.’” That legend was propagated by an academic conspiracy on the part of the socialists who controlled the teaching of history so that it required “exceptional independence of mind for a young scholar” to resist the pressure of anti-capitalist opinion.

This amazing charge has not a shred of substance to it. Whether the position of the working classes rose or fell as a consequence of the development of capitalism is a complex question, and one with which it is not necessary to deal here. More to the point is the evidence for the accusation that historians in their anti-capitalist zeal presented the issue unfairly.

… Enough for the logic of this vicious little book. But a word as to its significance. Given the climate of ideas of the early months of 1954 when this volume was published, no scholar could view with equanimity its irresponsible and false assertions that a whole generation of historians was anti-capitalist. Fortunately, these essays are likely to have little effect. Few capitalists fear they are thus threatened; and anyone who wishes seriously to examine the status and attitudes of the historical profession will learn those are al- together middle-class in complexion. That is why the essayists must be either embarrassingly silent as to who the anti-capitalist historians are or must resort to the outrageous distortions of Dean Hacker.”

pp. 102-6: “As always, Professor Nevins is meticulously careful in his use of sources, his efforts at accuracy are obvious, and his judgments are fair-minded and temperate. On points of detail he is thoroughly reliable; it is only on the large, important issues involving interpretation that he goes astray.

In these matters, the work is essentially apologetic. Professor Nevins does not distort his evidence, and on occasions he will even render a verdict against his hero. But the author nevertheless feels himself deeply involved in the defense of his subject, so deeply that he flinches at every aspersion on Rockefeller or his family (e.g., I, 4). …

Yet it is difficult to discover through these two long volumes a satisfactory definition of the nature of his achievement. He was not an innovator. Nor did he have the vision to anticipate long-term economic development. …

We would not know from Professor Nevins’ account, for instance, that the heart of the Standard Oil enterprise was its consistent and continuing illegality through the whole period of Rockefeller’s active connection with it. Through these decades, it profited always from preferential transportation rates which were sometimes though not always of critical importance in its growth (e.g., I, 249). Now, the conspiring to secure such exceptional treatment, whether in the form of rebates or otherwise, was not merely a matter of bad manners or of abstract ethics, as Professor Nevins incorrectly implies, it was a crime (I, 267). The law had made it so, even before it supplied the means for governmental review of rates. The railroads and other carriers involved were quasi-public bodies, chartered by the states and endowed with extraordinary powers, under certain limitations, among which was the rule that they extend equal non-discriminatory treatment to all those they served. The fact that the machinery of enforcement was weak and the provisions for redress imperfect did not make these rules any less binding as law.

Furthermore, the Standard Oil in its growth early took a path that involved illegal forms of consolidation. Aversion to monopoly was not simply an amiable quirk of the American temperament, as Professor Nevins casually describes it (e.g., i, 297; II, 155); it was aversion to a crime. For conspiracy to effect a monopoly in restraint of trade was illegal long before the Sherman Act. Statutes in the states derived from the common law were as old as the Republic. Yet Rockefeller’s tactics, repeatedly resorted to, consistently flouted the law in the furtherance of the interests of his own enterprise (i, 253 365, 366; II, 58, 335).

Thus the combination of transportation and refining activities was itself in the nature of a conspiracy, as the reaction to the development of the pipe line graphically illustrated. As a refiner, Standard Oil should have welcomed the appearance of a device which enabled it to lower costs. It did not, because the new means of transportation threatened to deprive it of advantages it enjoyed over the remaining independent refiners. It met the new situation by encouraging the railroads in a rate war to destroy the pipe lines (i, 237). When that failed, it attempted to eliminate the independents served by the pipe lines, and only as a last resort acquired a pipe-line system of its own which it later used against the independents (I, 298 ff, 345 ff).

The illegality of these combinations was plainly known to all those involved in them. … When the courts had the opportunity to pass upon the combination, they did not hesitate to find it criminal. Hence the eagerness of the Standard Oil to deprive the courts of that opportunity. Hence also the evasiveness of officials in testimony, their perjury, the destruction of records, the secrecy of proceedings, and the inability to reply to attack (e.g., I, 304, 305, 307, 386; I, 133 ff, 230 ff). All these tactics were not simply poor public relations as Professor Nevins considers them; they were rather the necessary response of men whose activities could not stand judicial scrutiny (i, 179, 210; II, 148).

The heart of the problem-how this truly religious and by his own lights honest man could for decades break the law of the land evades Professor Nevins. His full energies go rather to the elaboration of an intricate web of justifications for Rockefeller’s actions.

… For Professor Nevins … the ultimate justification for the Standard Oil tactics is that of efficiency. … The question is never confronted squarely. Yet there is occasional evidence, as in the resistance to such innovations as the pipe line, that efficiency was not the end or purpose of such combinations.”

Taylor 2019 Graham D. Taylor Imperial Standard: Imperial Oil, Exxon, and the Canadian oil industry from 1880 Calgary: University of Calgary 2019

pp.12-13, 51-52: “Ironically, Imperial had been established to be Canada’s defender against the sprawling tentacles of the Standard Oil”octopus” in the 1880s. … The Liberals in Canada systematically dismantled the protectionist measures that had shielded Imperial from the Americans. By the end of 1898 Imperial’s owners capitulated and the Standard Trust acquired control of a majority of the shares.

… [an agreement] of sweeping proportions … was quickly worked out … [in April 1898. It] … was a remarkably generous takeover (for [Imperial Oil] shareholders), which prevented many lawsuits from outsiders and criticism from the Canadian press. As usual, Standard had achieved its objective secretly.”

Spaulding 1993 William B. Spaulding “Why Rockefeller supported medical education in Canada: The William Lyon Mackenzie King connection” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History v10#1 (Spring 1993): 67-76

pp. 68-69: “Gates realized that Rockefeller [Sr.] was supporting Baptist causes with no master plan to guide the donations. To correct this, Gates introduced his”principles of scientific giving” which Rockefeller used as a guide to charitable support.

… One must agree with Howard S. Berliner, who pointed out, on the basis of the scant evidence available, that Rockefeller “had absolutely no idea what scientific medicine was nor did he care.””

p. 70: “In 1903, the New York State legislature authorized the incorporation of Rockefeller’s General Education Board, limiting its mandate to the distribution of funds to educational and research organizations within the United States. From the outset the Board was prevented by law from supporting endeavors in countries such as Canada.

… John D. Rockefeller, Jr. made a lifelong, full-time career of managing the disposition of the charitable funds donated by his father. After an apprenticeship with Frederick Gates, the son became convinced that Gates’s plan to support medicine was worthy of strong support. The two worked harmoniously together, the son being the faithful intermediary between the salesman Gates and the senior Rockefeller. John D., Jr., who served on the General Education Board from its first days, helped it become highly influential in supporting first general education, and then medical education and research. Deeply trusted by his revered father, whom he consulted about all major decisions, John D., Jr. soon became the major Rockefeller voice in determining how the family millions should be used to best effect. The elder Rockefeller, who had retired from active business in the 1890s, was in his sixties when his son took the helm.”

p. 71: “In 1913 Rockefeller used more of his fortune, $50 million worth of Standard Oil shares, to establish the Rockefeller Foundation. This important step expanded the scope of support beyond the limits of the activities of the General Education Board which were confined to the United States by statute. The new funds were used largely to support preventive medicine and medical education on a world-wide scale. The establishment of the Foundation allowed countries like Canada to become beneficiaries.”

Patnaik & Patnaik 2021 Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik Capital and Imperialism: Theory, history, and the present New York: Monthly Review 2021

pp. 113-20, 126-27: “Of all the different regimes that capitalism has built to overcome the problems it would face if it were indeed a closed and self-contained system, the ideal one from its point of view has been colonialism. …

… colonial possessions fulfilled several functions … they provided primary commodities for metropolitan capitalism; they provided these primary commodities gratis, as the counterpart of the economic surplus appropriated by the metropolitan economy …

The two main instruments used by the imperial powers in their colonies were capturing the colonial markets and appropriating a part of the surplus without any quid pro quo. Capturing colonial markets often required breaking down the natural economy …

Likewise, the appropriation of surplus took different forms, depending upon what had existed earlier. …

These two instruments were independent of each other but additive of their effects. They were independent in the sense that the extraction of surplus by the colonial rulers predated the quest for markets by the metropolis, which really began in the early nineteenth century and proceeded on its own trajectory. …

… The reason why the drain of surplus is not easily comprehended is that the balance of payments must always balance. … How then can we talk of “unrequited exports” from the colony? …

Conventional accounting obfuscates the drain for two distinct reasons. First, it is incapable of capturing the concept of an economic surplus. …

Second, conventional accounting is incapable of grasping that the purpose of colonialism is to extract this surplus; hence, to offset the surplus against the services rendered in the process of extracting it constitutes a supreme irony. It is like refusing to recognize the existence of an extortion racket on the grounds that the extortion money that is paid constitutes only the payment for the services of those who have come to collect the extortion money.

There is … a fundamental difference between a country’s experience after being colonized and all preceding experience. Not only is the surplus not spent on domestic goods as was the case earlier, thus giving rise to economic regression in the colonial economy, in the sense of a shrinking of the level of macroeconomic activity, but the colonial regime’s raison d’être lies in extracting the maximum amount of surplus. It does not simply take away some pre-set magnitude of surplus but adjusts its demands to whatever is available for it to take. …

The “drain of surplus,” in other words, did not just mean a replacement of the old set of surplus extractors by a new set, namely the old imperial regime by the new regime of metropolitan capitalism. … The colony did not witness a continuation of surplus appropriation as it had earlier. Rather, it became an appendage to another economy, which was never the case earlier. It is not surprising that modern mass poverty … arose for the first time in the third world economies only after they were colonized.

… There is a common misconception that the third world has always been afflicted by poverty, because of its low labor productivity that has continued to this day because it has not benefitted from the Industrial Revolution as the advanced capitalist world has done. … This conception is flawed in at least three important senses. … first … countries that did not develop capitalism could nonetheless have done so in emulation of the West, and ushered in an industrial revolution of their own as did Japan, the only major Asian country that escaped the tentacles of colonialism. What stood in the way of the backward economies developing their own “capitalism from above” through state initiatives, as in Japan, was colonialism itself …

Second, the impact of colonialism was actually to reduce the per capita incomes in the colonized countries and dependencies. … Hence the picture of all countries starting from a more or less similar situation and some forging ahead while others stayed where they were is wrong: those who forged ahead have the others a kick backwards.

Third, there is a fundamental difference between poverty that existed earlier and modern poverty that is associated with capitalism. Modern poverty is not just material deprivation; it involves … the loss of rights, even customary rights … and they creation of a reserve army of labor so that employment becomes uncertain on a daily basis—all these give a particular poignancy to poverty that did not exist earlier. This modern mass poverty is the legacy of the impact of metropolitan capitalism upon the third world.”

-

Brennan 2008 pp. 1-7 (Rosetown to Calgary), 11-15 (Ernest “The Echo” Manning)

Brennan 2008 Brian Brennan The Good Steward: The Ernest C. Manning story Calgary: Fifth House 2008

pp. 1-7: “His early life was shaped in Rosetown [post office founded 1907; village established 1909; town incorporated 1910], an isolated Saskatchewan hamlet where the wind never stopped blowing … Back in 1909, it was little more than a motley collection of clapboard shacks on a dirt main street flanked by two grain elevators. That’s when Manning’s father, George Henry Manning, a thirty-seven-year-old immigrant [at age 22] from the market town of Bury St. Edmunds in West Suffolk, England, filed sight unseen a homestead six kilometres southwest of the rural settlement.

Before arriving in Rosetown, George Manning had worked as a farm labourer in southern Manitoba and in southeastern Saskatchewan, where he established his first homestead [near Carnduff]. He told his future wife, twenty-four-year-old Elizabeth Mara (Bessie) Dixon of Kent that he would send for her when he settled. In the meantime, he encouraged her to continue working as a live-in lady’s maid at a stately home near Piccadilly Circus in London.

… Locals remembered Ernie as a happy-go-lucky youngster with a boyish sense of humour and a penchant for practical joking—in stark contrast to his later solemn image as a preacher and politician.

… Ernie’s favourite publications after Popular Mechanics were the mail-order catalogues from Simpson’s, Montgomery Ward, and Sears Roebuck that gave him ideas for other things he might spend his money on. In the fall of 1924, after a productive season of harvesting work, he sent a $103 [$1,747.57 in 2022$ at the age 14?] money order to Sears Roebuck in Chicago to buy a three-tube Philco radio receiver complete with dry-cell batteries, gooseneck loudspeaker, and nine-metre stranded-wire aerial. … the Rosetown postmaster was holding was holding the equipment pending payment of customs duty. Ernie finally took delivery of the equipment pending payment of customs duty on 24 December 1924, just as the postmaster was about to put it up for sale. …

The radio proved to be a fateful acquisition. If he was looking for direction in his life, Ernie found it in a religious broadcast featuring the fire-and-brimstone voice of William Aberhart, a forty-seven-year-old Calgary high-school principal and self-taught Bible scholar …

… To the seventeen-year-old Ernie Manning, Aberhart’s preaching was a revelation. Although he occasionally attended Methodist Church in Rosetown with his family, Manning considered himself little more than a nominal Christian at best. … “He brought about a complete transformation in my life,” said Manning. “My interests changed, my outlook on life changed. …” …

In February 1927, when there was little work to do around the farm, Ernie donned an ill-fitting suit purchased from the mail-order catalogue and rode the CPR train to Calgary to introduce himself to Aberhart. … Throughout the spring and summer of 1927, he listened to the radio on Sundays when Aberhart spoke of his plans to build a Bible college in downtown Calgary.

Aberhart raised a total of sixty-five thousand dollars for the construction of his college [$1.1 million in 2022$] … In the fall of 1927 he announced over CFCN that the school would open on 30 October. … When Ernest Manning heard the news, he felt called … He left the farm, moved to Calgary, and was the first of thirty-five students to enrol when the Bible Institute opened. …

… Ernest Manning used the proceeds from the harvesting he and his brothers did for their neighbours in Rosetown to pay for his first term’s room and board … After that he accepted an invitation to live with the Aberharts—William and his wife Jessie—in a ground-floor suite adjoining the garage of their newly built … hillside home … in Calgary’s Mission district. The Aberharts had two adult daughters older than Manning … but no sons. William … said in later years that he soon came to regard his young student as the sone he never had.”

pp. 11-15: “In his last year as a student, Manning also taught as a volunteer at the Institute. … In April 1930, at age twenty-one, Manning became the Institute’s first graduate. Three months later, Aberhart headed off to Halfmoon Bay, fifty kilometres north of Vancouver on British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast, for his annual summer holiday … He asked Manning to mind the house for him and fill in for him on the radio. From that point on, they were a team. …

Manning worked as Aberhart’s full-time assistant, running the Institute as secretary-manager and sharing the radio broadcasts … Aberhart started purchasing airtime on CFCN in 1930 …

On air Manning mimicked Aberhart’s delivery so effectively that he became known as “The Echo.” “I picked up many of his mannerisms,” Manning recalled. “…Yet, I think I’m quite truthful in saying that our personalities were fundamentally different. We were different types of people altogether. But in the public eye I reflected a great deal of what they were accustomed to from him.”

… In the summer of 1932, Aberhart underwent a political conversion that has become legendary in Alberta history. … During a trip to Edmonton … Aberhart found what he saw as the solution to Alberta’s economic problems in a book … by a British stage actor … Unemployment or War offered a summation of the radical monetary reform theories developed by England’s Major Clifford Douglas. …

… Social credit, he decided, was exactly what the people of Alberta needed to save themselves from the economic hardship caused by Eastern bankers and financiers.

… the philosophy of social credit, which Preston Manning has described as a mixture of “pre-Keynesian economics, social resentment, and untutored hope.””

-

Manning 2011 pp. 2-3 (youngest minister); Richards & Pratt 1979 pp. 78-80 (‘entice outside capital’); Brennan 2008 pp. 28-29 (Aberhart distaste for Bankers’ Money), 56-69 (state credit houses)

Manning 2011 Preston Manning and Peter McKenzie-Brown Interview transcript Petroleum History Society Oil Sands Oral History Project (21 October 2011): 20pp

footer: “Sponsors of The Oil Sands Oral History Project include the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation, Athabasca Oil Sands Corp., Canadian Natural Resources Limited, Canadian Oil Sands Limited, Connacher Oil and Gas Limited, Imperial Oil Limited, MEG Energy Corp., Nexen Inc., Suncor Energy and Syncrude Canada.”

pp. 2-3: “… there had to be some solution to the Depression, and so [Aberhart] picked up this social credit idea that was circulating at that time in England and started to talk about it on his radio program, half of it was now religious, the other half was, what’s the answer to the problems of the Depression. And of course, out of that came some study groups who ended up deciding to run candidates in the 1935 Provincial Election in Alberta, on this social credit idea … sort of a ‘Poor Man’s Keynesian Economics.’ … Aberhart was not in favour of these study groups going into politics. He saw himself as an educator but they ran candidates. Anyway, my father ran as one of these first candidates, he got himself elected …

… I think he was 26 or something like that. He ended up being the youngest cabinet minister in the British Empire at that time and of course, in the 1935 election, Albertans threw every last member of the government out of the house and put in these new people. My father said the only thing that you had to be able to assure the electorate in 1935 was that you’d never set foot in the legislature before, and that was enough to qualify you. So he ended up then in the government because Aberhart was called upon to run himself and become the Premier. And then when Aberhart died in 1943, my father succeeded him and was Premier right up until he retired in 1968.”

Richards & Pratt 1979 John Richards and Larry Pratt Prairie Capitalism: Power and influence in the new west Toronto: McClelland & Stewart 1979

pp. 78-80: “From the date of their landslide victory in 1935, Social Credit’s leadership made it clear that the radical thrust of their right populist movement was not directed at the oil industry. In the desperate economic circumstances of the great depression, with Alberta deeply in debt, Social Credit was eager to entice outside capital into the search for oil. Premier Aberhart telegraphed assurances to the financial press and the oil trade bulletins that the province intended to give every incentive to risk capital.

In 1936 Aberhart appointed Nathan Eldon Tanner to be Minister of … Mines and Minerals … More than any other Alberta politician, including Ernest Manning, Tanner was the real author of the province’s regulatory system for oil and gas. … Tanner put in place most of the complex administrative apparatus … before leaving politics in 1952 to make his fortune in oil and gas, notably as the first president of Trans-Canada Pipelines; today [1979] he is a senior Elder in the Mormon Church hierarchy in Salt Lake City, Utah …

A conservative small businessman as well as former Mormon bishop and high school principal at Cardston, Alberta … Tanner’s department imported officials from the Texas Railroad Commission and other U.S. agencies to supervise the creation of Alberta’s Oil and Gas Conservation Board and to devise schemes for reducing the wastage of oil and gas in the Turner Valley. … While much of the legislation was incrementally amended and revised, and some new mechanisms were introduced after 1947 in response to the pressures of expansion, it was, as we have seen, in the late 1930s that the basis of the regulatory structure was conceived and passed into law. Profoundly conservative in its emphasis upon property rights and strongly influenced by the regulatory tradition of the southwest United States, much of this structure persists today and is now deeply imbedded in the statutes of Alberta and in the corpus of Canadian oil and gas law.

To some Social Credit supporters Nathan Tanner’s campaign to attract development money to Alberta was nothing short of betrayal. Standard Oil was about as popular among prairie populists as the CPR or any other outside monopoly. … One of Aberhart’s admirers protested … “… If outside interests can come in and make big profits why can’t we operate them ourselves and keep the money here?””

Brennan 2008 Brian Brennan The Good Steward: The Ernest C. Manning story Calgary: Fifth House 2008

pp. 28-29: “Aberhart, with his distaste for what he called”bankers’ money,” was not about to accept any of Douglas’s suggestions that might involve dealing with Eastern financial institutions. Instead he travelled to Ottawa and asked Prime Minister R.B. Bennett, a fellow Calgarian who had publicly expressed his support for Social Credit (though privately he suggested that Albertans were “sacrificing their judgement to their emotions”), for a federal loan of $18 million. Bennett agreed to give just $2.5 million, which he said should be enough to prevent Alberta from declaring bankruptcy prior to the upcoming October federal election. In return, Aberhart assured Bennett that a federal Social Credit candidate would not oppose him in Calgary.

… Bennett kept his seat in the 1935 election but his party lost the election to Mackenzie King’s Liberals. They undertook to lend Alberta enough money to pay off a $3 million bond issue due to mature on 1 December. King warned there would be no more funds forthcoming after that until Aberhart agreed to put Alberta under the jurisdiction of the Canada Loans Council, which supervised provincial borrowing. This Aberhart refused to do …”

pp. 56-59: “On 4 March 1938, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down all the statues passed by the provincial legislature in the name of social credit, including the bank licensing act … Aberhart, who fully expected the Supreme Court reversal, announced that his government would appeal the decision to the British Privy Council, then Canada’s court of last resort. …

Ernest Manning, the loyal disciple who never criticized Aberhart’s policies, always defended the bank licensing act … as [a] reasonable piece[] of legislation. …

One piece of social-credit legislation not challenged in the courts or disallowed by the federal government was the 1936 Act providing for the establishment of what were first called “state credit houses”—provincial savings and loan institutions that would eventually become an established feature of Alberta’s financial life. These were the institutions through which the long-promised twenty-five-dollar dividends were to be paid whenever the government could eventually afford them. They started opening in 1938 … as branches of the provincial treasury department that had the power to issue “non-negotiable transfer vouchers” as a form of purchasing credit. Nowhere in the legislation was the word “bank.” In fact, one of the existing charter banks, the Imperial Bank of Canada, was appointed to act as the agent and financial backer for the Treasury Branches so that they would not violate the federal government’s jurisdiction over banking and currency.”

… when the first cabinet ministers and then the civil servants agreed to accept a quarter of their salaries in Treasury Branch vouchers, public resistance began to soften. …

… Because they posed no threat to the major chartered banks, which tolerated them as an anomaly—a weak Western cousin, as it were—the Treasury Branches never had to face a constitutional challenge until the 1960s. … both the Alberta Appeals Court and the Supreme Court of Canada implied but did not definitively rule that the Treasury Branches were unconstitutional. Thirty years later, in 1997, the original 1938 Treasury Branch legislation was repealed, and the Branches became a provincial Crown corporation operating under the name of ATB Financial. By 2003, ATB Financial—North America’s only state-owned retain financial institution—was proudly promoting itself as Canada’s eighth-largest commercial bank, with 276 branches and $13.2 billion in assets. Nobody seemed inclined by then to press the point in the courts that, according to the [1982] Canadian constitution, the Parliament of Canada still had exclusive control over “all matters relating to banking and incorporation of banks.”

-

O Ascah 1999 pp. 142-43 (brain trust w/ latest economic theories), 148 (default), 53, 129 (unsympathetic feds), 140-41 (Bank of Canada & chartered banks closer); Tribe 2021 pp. 5, 31, 34, 31n37, 304-05n, 195, 331, 334-35, 34, 312-13 (Rockefeller founding of economics) & De Vroey 1975(transition from classical to neoclassical economics); Breen 1993 pp. lviii-lxii (FOCB-NIRA), 104-7 (Aberhart’s patriotism), 106-9 (Manning taps Tanner), 110-11, 116 (AB production curtailed), 118-29 (Tanner telegraphs DC), 154, 143, 129, 134-41, 157-58, 145-47 (‘effectively shielded from legal challenge’); Oil and Gas Resources Conservation Act 1938 s.44 + s.46, pp. 13-14

Ascah 1999 Robert L. Ascah Politics and Debt: The Dominion, the banks and Alberta’s Social Credit Edmonton: University of Alberta 1999

pp. 142-43, 148, 53, 129, 140-41: “Canada’s dependence on international capital markets changed significantly after the Great War. From a situation of utmost dependence on London for capital, the Dominion Government was, in effect, reliant on Toronto and Montreal financial institutions and wealthy individuals. The Dominion’s foreign borrowing shifted away from London to New York as the Dominion tapped the US dollar market for relatively modest sums. (See Appendix B.) …

Canada’s evolution as a nation independent from the United Kingdom was not only a political one, it was also financial. As the Dominion organized to become financially self-sufficient, its financial interests were in a sense domesticated. Domestic investment dealers, such as A.E. Ames and Wood Gundy, assumed a bigger role. The whole controversy at the time of the Bank of Canada’s establishment—that this institution was part of conspiracy to put Canada under imperial domination—reinforced Canadians’ desire to work outside the control of London.

During the Depression, the financial apparatus of the Dominion was modernized. Ottawa was able to attract a brain trust of remarkable public servants, principally educated at graduate schools in the United Kingdom or the United States, and equipped with the latest economic and financial theories. This nucleus gave the Dominion a new energy and intelligence to address complex financial and economic problems. This team of public servants oversaw the establishment of a central bank, the isolation of the Alberta Social Credit administration, a very successful wartime debt management program, and a new set of financial institutions such as the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

… On April 1, 1936, Alberta was Canada’s first, and only, province to default on a principle debt payment. In this unusual case of a default, the interests of a government debtor and institutional creditors clashed. The Dominion government recognized the importance of meeting the expectations of finance capital but Alberta’s provincial government was committed to thwarting the claims of finance capital. …

… Following Alberta’s default, the Dominion was unsympathetic to assisting Alberta financially until it made restitution with holders of bonds in default. It was only after Aberhart’s death and Provincial Treasurer Solon Low’s departure for Ottawa that representatives from Wood Gundy and The First Boston Corporation met with Premier Ernest Manning, Deputy Provincial Treasurer Frank Percival and the Provincial Auditor Keith Huckvale, to work out a debt reorganization plan. On June 6, 1945, the Alberta Cabinet passed Order-in-Council 925/45 that outlined the government’s debt reorganization program.

… The Alberta aberration teaches us lessons about the nature of public debts and the importance of good debt management. First of all, the crisis of Alberta public finance demonstrates the dangers to the issuer of the optional-payment bond and more generally the special difficulties of foreign borrowing. …

The conditions for Alberta’s default included objective financial circumstances but also subjective factors such as feelings of alienation and victimization wrought by finance capital and conflicts with the Dominion over financial sovereignty. …

After analysing the initiatives taken by the Province and the reaction of the chartered banks to these measures, the protection of the Dominion’s credit standing could only be served by Alberta’s default. The great fear that Social Credit would spread like a prairie fire was implicit in many editorials and communiques by bankers, lawyers and Dominion officials. The Dominion concluded that Alberta, which had moved too far in interfering with federal prerogatives, should be cut adrift in order for the Dominion to maintain credibility with the international and domestic financial communities.

The default also served to build a close working relationship between the new Bank of Canada governor and the chartered banks. This close co-operation preserved the constitutional authority of the Dominion in the sphere of banking, credit, currency and interest.”

Tribe 2021 Keith Tribe Constructing Economic Science: The invention of a discipline 1850-1950 New York: Oxford University 2021

pp. 5, 31, 34, 31n37, 304-05n, 195, 331, 334-35, 34, 312-13: “The discipline of economics was long in the making, but the reason it eventually became a discipline was owed to international changes in schooling and university towards the end of the nineteenth century.

… by the turn of the century organized benefaction on the part of philanthropic foundations began to displace individual generosity. Chief among these were the General Education Board founded in 1902 with $1 million from Rockefeller.

… The emergence of the department as the basic element of university organization for teaching and research is therefore directly related to the development of specialization as the typical form for training new researchers and for the advancement of knowledge. By the 1890s this organization form had become established in the United States, most notably in the systematic foundation of whole departments in Rockefeller’s University of Chicago. … many of them established journals that were immediately recognized at an international level.

… there was a strong tendency by the 1930s for LSE [London School of Economics] economists to presume that reality ought to conform to theory. This attitude was exemplified by Lionel Robbin’s The Great Depression (1934), which argued that governments could do nothing to mitigate unemployment and that prosperity would return only if the market were permitted to work without hindrance. This was likewise the view of Friedrich Hayek, who was recruited to the LSE in 1931.

… When Cannan retired in 1926, Beveridge initially favoured appointing Ralph Howtrey to the vacancy; but the School had received a grant from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Fund that made it possible both to convert Cannan’s part-time post into a full-time one, and look further afield for a candidate. In the spring of 1926, Beveridge offered the post to Allyn Young of Harvard, who after prolonged negotiations accepted for a term of three years in January 1927.

… Robbins had gained a First in the BSc (Econ) in 1923, then after a period as a research assistant to Beveridge been appointed for the 1924-25 as a temporary lecturer at New College Oxford, standing in for Harold Salvesen, who went to the United States on a Rockefeller grant. He returned in the autumn of 1925 to LSE as an assistant lecturer with a relatively light teaching load, and was then promoted to a full lectureship in June 1926 in response to moves to recruit him to Cambridge.

… Allyn Young died in March 1929, and Beveridge, seeking to plug the gap in teaching that this created, first persuaded Robbins to take over economic theory classes running up to the June examinations, and then in May decided to invite Robbins to return to a ‘junior’ professorship at LSE.

… using Rockefeller money to signal the international standing of the School in the developing field of economics … Student demand for such an apparently wide-ranging programme did not yet exist … taken together, these factors are suggestive of hasty improvisation, more of a concern to make a point than to make a change.

… Hayek’s account of the School up to the mid-1940s makes very clear that after 1920 this altered into a fulltime model for both staff and students, with school-leavers coming to predominate among the student intake. … By the later 1940s economics was at last becoming a popular subject to study, and the LSE was perceived as central to such study.

… the strategic advantage enjoyed by the LSE within the organisation of British higher education [at the center of empire] meant that the postwar expansion of the social sciences would extend its reach yet further. And of course, the 1963 landmark study of the future of higher education in Britain would be headed by its professor of economics, Lionel Robbins.”

De Vroey 1975 Michel De Vroey “The transition from classical to neoclassical economics: A scientific revolution” Journal of Economic Issues v9#3 (September 1975): 415-39

Breen 1993 David H. Breen Alberta’s Petroleum Industry and the Conservation Board Edmonton: University of Alberta and the Energy Resources Conservation Board 1993

pp. lviii-lxii: “To check the pattern of discovery, followed by frantic development, flush production and great waste, then sharp decline, Texas passed a general waste prevention statute in 1919 that gave wide regulatory powers to the Railroad Commission and became the basis of subsequent statewide oil and gas regulation.

The next phase of regulatory development was greatly shaped by the ideas and advocacy of Henry L. Doherty … who “enjoyed his role as the intellectual of the petroleum industry” … Doherty is recognized as one of the fathers of modern conservation practice. … A director of the American Petroleum Institute (API), he decided to first take his reform ideas to his fellow directors … The API reception was less than enthusiastic … Unable to convince the directors of the Institute, Doherty called upon his friend Calvin Coolidge at the White House in the fall of 1924. Also urging the president to give special attention to the conservation to petroleum resources was Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work … Prompted by Doherty, Work and his own concern about national security needs, Coolidge created the Federal Oil Conservation Board (FOCB) in December 1924. This action by the president had the extremely important effect of identifying petroleum conservation as a matter of national concern, and it greatly stimulated discussion and research in petroleum problems.

The FOCB was composed of the secretaries of war, the navy, the interior and commerce. …

Between 1926 and 1933, the FOCB issued a series of reports to the president urging the promotion of uniform state conservation regulations consistent with the principles of reservoir mechanics. Unit operation was presented as the ideal. … In its final report in 1932, the Board presented a specific proposal for an interstate compact that would permit a state-federal agency to forecast demand and allocate production quotas to producing states. …

By the time of the FOCB’s final report, the situation facing the oil producers and the oil-producing states was desperate. … A dramatic new surge of production commenced just as the impact of the Great Depression and declining demand had begun to be felt. … In Texas, … Governor Sterling had been compelled in August 1931 to declare martial law and send the National Guard into the East Texas oilfield to protect life and property as producing oil wells were shut down. A similar situation saw troops sent into the Oklahoma City field.

In this desperate environment, prejudice against federal participation eased, and the prospect of a joint federal-state conservation board along the lines suggested by the FOCB appeared bright. With the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in November 1932, however, the FOCB became defunct, the compact idea was dropped, and the problems of the petroleum industry were approached in a different manner. … far-reaching and unprecedented system of import restriction, minimum prices, administration approval of new reservoir development plans, limitation of domestic production to total demand less imports … Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes was anxious to go even further, and to have the oil industry declared a public utility and regulated accordingly. …

By the end of 1933, many oilmen rated [Roosevelt’s] Oil Code a great success: production had been cut back, prices had firmed and begun to move upward, and the industry showed signs of stabilizing. …

… In June 1935, the Supreme Court declared the entire [National Industrial Recovery Act ] unconstitutional, which meant the end of the Oil Code. … it was also apparent that there was strong opposition to any direct federal regulatory role among a large segment of the industry, especially in Texas. Federal control of production and distribution of petroleum promised to be a Herculean task fraught with political hazards.

Roosevelt was not inclined therefore to challenge the initiative already taken by several of the large oil-producing states. Governor … James Allred of Texas … was unalterably opposed to the principle of conservation regulation for the purpose of price control. Allred would consider only the matter of preventing physical waste, and this he believed was solely the business of the State of Texas. Prepared to concede to federal regulation of some form of hot oil law and restriction of foreign oil imports, he would not countenance any further participation. Allred proposed therefore an interstate compact that would promote the standardization of state conservation laws.

… patterned essentially on the Texas proposal … Congress formally ratified the agreement, establishing the “Interstate Compact to Conserve Oil and Gas” on 27 August 1935.”

pp. 104-7: “… Aberhart looked upon the matter as a politician … who had solemnly pledged to end”poverty in the midst of plenty,” Aberhart was not prepared to chance any measure that could put development at risk. His inclination in this direction was strengthened by his bias in favour of the “little man.” The cry of the small producers, that quotas would benefit the big operators, especially Imperial Oil, at their expense, seems to have weighed heavily. Aberhart saw the big eastern banks holding Alberta in bondage, and it was not hard for him to see the Toronto-based Imperial Oil Company in the same light.

Differences between the premier and his minister of lands and mines remained irreconcilable. When he learned in late December that Ross was planning to shut certain Turner Valley gas wells, Aberhart asked for and received his resignation.

… previously at the Edmonton district Social Credit convention … Delegates had censured C.C. Ross, the former minister of lands and mines, and passed a resolution declaring that “outside capital was not required” and “should not be allowed to participate” in the development of Alberta’s resources.”

pp. 106-9: “Late one evening, just before Christmas, [Nathan] Tanner was awakened by a telephone call from the premier. Aberhart wanted to know if Tanner would accept an unidentified cabinet position … followed several days later by a wire asking Tanner to come to Edmonton”as expeditiously as possible” to assume the position of minister of lands and mines.

… Born in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1898, Tanner grew up in the staunchly Mormon community of Cardston, just 17 miles north of the Alberta-Montana border. …

… The new minister … had no previous connection with the petroleum industry or, for that matter, any other business enterprise. … he nonetheless began his term as minister of lands and mines with one advantage that Ross had never been able to claim. This was the complete confidence of both the premier and Ernest Manning, his most trusted disciple. Tanner was also inheriting a department that had the singular distinction of not being in utter destitution and totally dependent upon the near-bankrupt provincial treasury.

… throughout the winter and spring of 1937 … the evidence of the growing interest of eastern Canadian capital remained the focus of press, public and government attention … At a banquet organized by the Oil and Gas Association of Alberta to introduce Tanner to the industry, the minister assured his audience that it was “going to be one of the greatest development years in the history of the province,” that he did not “favour numerous investigations into the oil industry,” and that the policy of his department “would be to protect investors as far as possible.” … The assembled oil men were reassured, especially by Tanner’s implied message that he would be guided in his actions by the professional staff in his department rather than by some of the more extreme anti-business elements within the Social Credit caucus. Dr. Link, Imperial Oil’s chief geologist, was quick to second Tanner’s wise decision to discuss oil problems with such able members of his staff as “‘Charlie’ Dingman, Grant Spratt and Vernon Taylor,” and he pronounced the minister “OK.” Dr. R.J. Manion, a former federal minister of railways, and engineer-businessman Major-General G.B. Hughes, both of whom had travelled from Toronto so that they could use the meeting to announce a half-million dollar six-well drilling program, declared themselves favourably impressed with Tanner. They advised members of the oil industry “to co-operate, regardless of political opinions, with a man who was evidently sincere and determined to do his best.””

pp. 110-11: “As spring turned to summer [in 1937] … At Turner Valley, the wasteful flaring of natural gas continued unabated, and the press continued to chronicle the successful completion of additional oil wells. Increasingly, Turner Valley appeared as an oasis of prosperity in the otherwise bleak economic landscape.

Albertans and Turner Valley operators were jolted into reality in early September when Imperial Oil and the British American Oil Company announced simultaneously a sharp reduction in the price their refineries would pay for crude. … The price decrease underlined dramatically that the petroleum industry in Alberta had entered a new phase. Production had moved well beyond what the local market could absorb, and Alberta passed from the status of importer to exporter of oil.

… Although officials of Imperial Oil and British American, the major refiners of Turner Valley crude oil, proclaimed that prorationing was now in effect, independent oil companies countered with a statement saying that they had not agreed to prorationing at the meeting with Tanner. … They concluded: “The absurdity of proration being necessary with a daily production of ten thousand barrels should be apparent when it is realized that this amount is but a fraction of the daily Canadian requirements, the balance being imported and a considerable amount coming from Montana.””

p. 116: “It was the”New Year’s message” of J.H. McLeod, president of Royalite Oil Company, and the resultant howl from Turner Valley crude oil producers, that finally jolted the Social Credit government to act. On 4 January 1938, McLeod announced that the price announced that the price of Montana crude had collapsed, that there was now no recognized posted price, and that distress prices were in effect. “Consequently,” McLeod declared, “certain steps must be taken to assure Turner Valley of its market on the prairies.” … The next day, the Calgary Herald reported that … an all-out “crude war” threatened.

Ten days later, N.E. Tanner announced that conservation legislation would be introduced at the forthcoming session of the Alberta Legislature. … In his desire to consult closely with the operators, Tanner was following the practice established from the first by the Department of the Interior’s Petroleum and Natural Gas Division and later followed by the United Farmers of Alberta. Once adopted by Tanner, the emphasis on consultation with the industry on conservation matters also remained characteristic of Tanner’s Social Credit successors [under Manning].”

pp. 118-29: “On March 17 [1938], [Tanner] telegraphed J.W. Finch, director of the Bureau of Mines in the Department of the Interior in Washington, to … ask the director if he would recommend the names of competent petroleum engineers experienced in this area who might be prepared to come to Alberta. From the list of names submitted, Tanner selected the firm”Parker, Foran, Knode & Boatright,” a group of consulting engineers in Austin, Texas, who had been influential, Finch explained, in the formulation of conservation legislation in Texas. … Before establishing his own consulting firm, Parker had headed the Texas Railroad Commission for 26 years … Unavailable himself, Parker recommended his colleague, W.F. Knode. … [whose] father owned a torpedo company that “shot wells” to improve oil flow, and … got his first oilfield job at the age of eight. … he worked for various companies in … northern Oklahoma … Kansas, New Mexico and Venezuela. Employed by Shell Oil in west Texas in the Late 1920s, Knode was on hand to observe the formation of the Central Proration Committee by independent operators in that region. …

… If a new conservation authority was not to suffer the fate of the Turner Valley Gas Conservation Board [ended by Supreme Court in October 1933], it was necessary that the Canadian Parliament pass an appropriate amendment to the 1929 Natural Resources Transfer Agreement. … Thus, on the day that Tanner’s telegram went out to W.F. Knode in Corpus Christi, Texas, another telegram was on its way to Ottawa from Tanner’s deputy minister. This second telegram expressed the Aberhart government’s anxiety that the Transfer Agreement amendment of the Alberta Legislature was nearing its end. Prime Minister Mackenzie King, however, was little inclined to take any action for the convenience of the Alberta premier.

… The Oil and Gas Conservation Act assented to 8 April 1938 was necessarily restricted by a clause stating that the Act would only come into force on a day proclaimed by the lieutenant-governor-in-council after Parliament had ratified the agreement reached on March 5.

… Alberta legislators were not reticent about granting the Board sufficient power to effect its purpose. The Board was given the right to summon witnesses, to issue commissions, and to take evidence outside the province, and in its hearings it was to be governed by its own rules of conduct rather than being bound by the technical rules of legal evidence. A decision by the Board upon any question of fact or law within its jurisdiction was binding; no Board order, decision or proceeding could be appealed. Finally, no officer or employee of the Board was personally liable for actions carried out under the authority of the Act. The panoply of powers vested upon the commissioners, especially the denial of right of appeal, seems at first glance to stand in contradiction to the democratic impulses traditionally ascribed to agrarian reformers. …