The Paradox of Individualism and Hierarchy

June 26, 2021

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

In the early 1970s, Geert Hofstede discovered something interesting. While analyzing a work-attitude survey that had been given to thousands of IBM employees around the world, Hofstede found that responses clustered by country. In some countries, for instance, employees tended to prefer an autocratic style of leadership. But in other countries, employees preferred a democratic approach. These differences, Hofstede proposed, were caused by culture.

Today, Hofstede’s work has blossomed into the field of ‘cross-cultural analysis’. It’s a vibrant discipline that looks at how attitudes and beliefs vary between societies. The tools of the trade are simple surveys and questionnaires. But the goal of cross-cultural analysis is ambitious. It aims, as Hofstede puts it, to understand the ‘software of the mind’.

✹ ✹ ✹

Geert Hofstede didn’t invent the idea that culture varies between societies. (That idea is probably as old as culture itself.) But he did pioneer the quantification of culture. Before Hofstede, there was much grand theory, but little measurement. Theories of culture date at least to the Greeks, who were perhaps the first to give culture a name. (They called it the nomos.)1 The modern theorization of culture, however, probably began with sociologist Max Weber.

Like many social scientists, Weber wanted to understand the origin of capitalism. Why, he asked, did capitalism arise in Western Europe? His answer was that Westerners had adopted a peculiar attitude towards work — what Weber called the protestant work ethic. Rather than see work as a chore, protestants (especially Calvinists) saw industriousness as a virtue. This culture shift, Weber argued, was key to understanding the emergence of capitalism. Without the idea that work was a virtue, people would meet their basic needs and then relax. But when work became a goal in itself, the wheels of capitalist accumulation were set in motion.

While Weber’s specific hypothesis may not be correct, it’s now clear that he was onto something. The transition to capitalism came with a host of changes in people’s worldview. Evolutionary psychologist Joseph Henrich calls it becoming WEIRD. This is his acronym for ‘Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic’. It’s a clever double entendre because people in WEIRD countries are legitimately weird. From visual perception to attitudes about cooperation, WEIRD people have psychologies that differ from the rest of the world. (For an exposition, see Henrich’s seminal paper The weirdest people in the world?)

That brings us to economics. Like Weber, economists explain the origin of capitalism in terms of a cultural shift. But rather than focus on work ethic, economists focus on exchange. It’s the belief in unfettered market exchange, they claim, that leads to economic development.

Interestingly, the quantification of culture seems to support this view. People in developed countries tend to be more individualistic than those in less developed countries. WEIRD people also tend to be more skeptical of autocracy and more receptive to norm-shirking behavior (behavior that economists would call ‘innovation’). This evidence seems to support the narrative (cherished by economists) that economic development is a product of the free market.

A paradox

Although WEIRD psychology fits well with the free-market narrative, it’s not clear that this narrative is actually true. In fact, there’s good evidence that economic development involves not the spread of the market, but rather, its death.

Industrialization is associated with the growth of large institutions — big firms and big governments. (See Energy and Institution Size for a review of the evidence.) Look within these big institutions and you won’t find a free market. Instead, you’ll find a chain of command that concentrates power at the top. In an important sense, then, economic development involves not the spread of the free market, but the growth of hierarchy. (For details, see Economic Development and the Death of the Free Market.)

If industrialization involves the growth of hierarchy, we’re left with a paradox. Developed countries are both more hierarchical and more individualistic than their less-developed counterparts. How can this be true?

I explore here an interesting possibility. What if individualism does the opposite of what we think? Rather than promote autonomy, might individualism actually stoke the accumulation of power? This idea sounds odd at first. But I hope to convince you that it’s plausible.

Narrative 1: Developing through the free market

We’ll begin our journey into culture by looking at the evidence for cultural change. I’ll first look at this evidence in a way that supports the free-market narrative. Afterwords, I’ll turn this narrative on its head.

To get into the free-market mindset, we’ll drink the neoclassical Kool-Aid. According to neoclassical economics, the best way to promote economic development is to liberate self-interest. Let people act for their own gain, say economists, and economic development will take care of itself. This concept of the ‘invisible hand’ defies the ethic (ingrained in many of us from birth) that selfishness is a vice. In economic theory, selfishness is a virtue.

Despite its counter-intuitiveness, the idea of the invisible hand seems to be supported by cross-cultural analysis. As societies industrialize, the following cultural shifts tend to occur:

-

People become more individualistic.

-

People become more skeptical of authoritarian power.

-

Norms weaken and people become more tolerant of deviant behavior.

In general, then, economic development comes with greater autonomy of the individual — at least as perceived by cultural ideals.

Individualism

Let’s look at the evidence for culture shift. We’ll begin with a measure of culture pioneered by Geert Hofstede. Based on his analysis of IBM employees, Hofstede proposed a cultural spectrum between ‘individualism’ and ‘collectivism’. Hofstede describes this spectrum in Table 1.

Source: Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context

Source: Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context

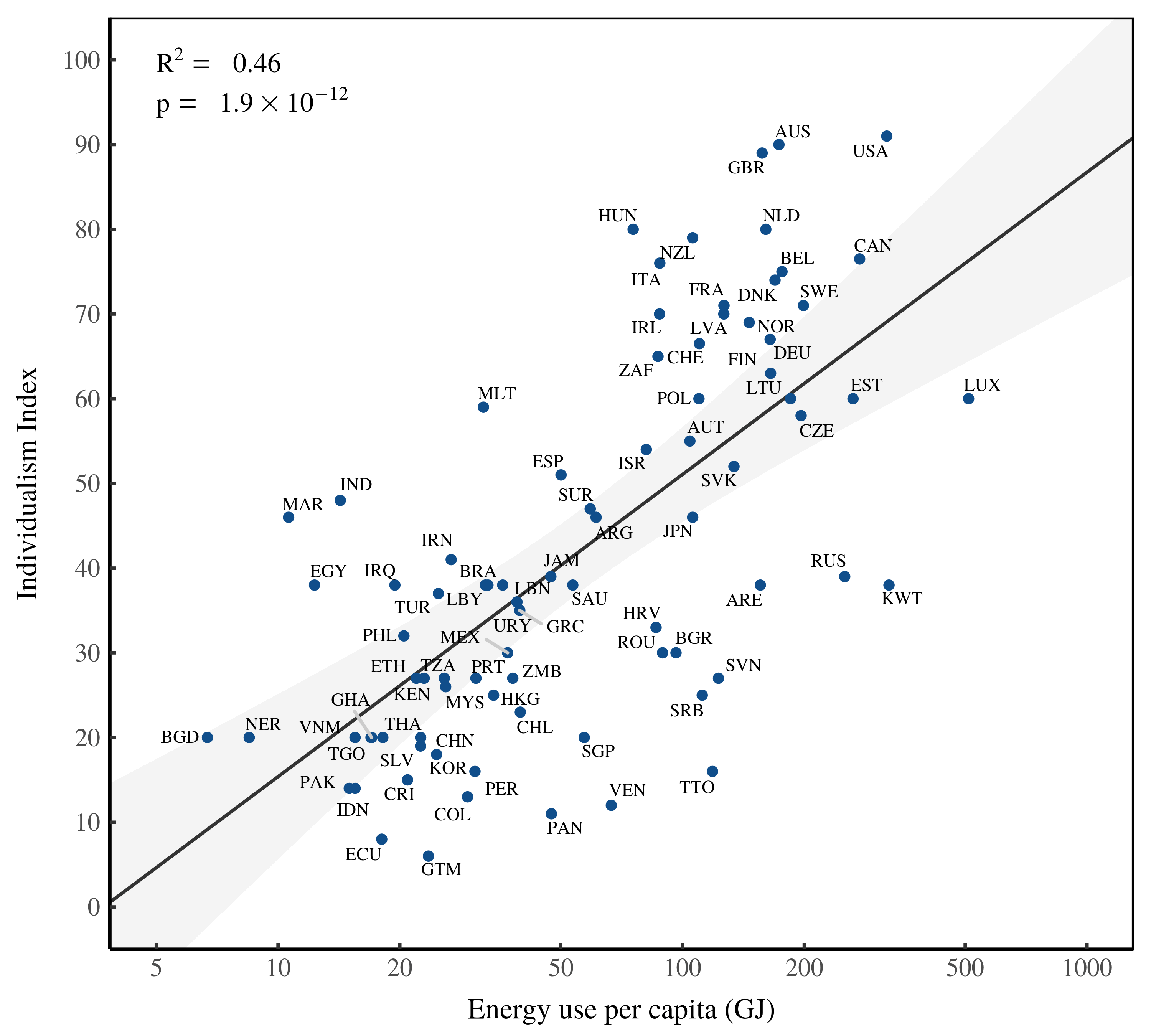

To measure the individualism-collectivism spectrum, Hofstede created the ‘individualism index’. The larger this index, the more individualistic the culture. In Figure 1, I’ve plotted Hofstede’s individualism index (in different countries) against energy use per capita. Individualism, it seems, tends to increase with industrial development. So the evidence suggests that if you let individuals pursue their self interest, economic growth will take care of itself.

While the results in Figure 1 seem straightforward, there’s an important caveat. It’s not clear that Hofstede’s individualism index actually measures what he claims. Hofstede created the index by weighting responses to a dozen or so questions, assigning some responses to the ‘individualist pole’ and others to the ‘collectivist pole’. Unfortunately, it’s not obvious that the questions on the ‘collectivist pole’ are actually related to collectivist ideology. But despite these problems, Hofstede’s results have been replicated using more credible metrics.2 So it seems safe to conclude that people become more individualistic with economic development. Point for the free-market narrative.

Power distance

Let’s move on to another cultural metric pioneered by Geert Hofstede — one that he calls the ‘power distance index’. This index measures the degree to which people believe in autocratic rule. When people are skeptical of autocratic rule, the ‘power distance’ is small. But when people believe that autocracy is ‘natural’ (and that obedience is a virtue), the ‘power distance’ is large. Hofstede describes the two poles in Table 2.

Source: Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context

Source: Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context

In Figure 2, I plot Hofstede’s power distance index against energy use per capita. As energy use increases, power distance tends to decrease. This indicates that as societies industrialize, people become more skeptical of autocratic rule.

As with the trend towards individualism, this growing skepticism of power fits with the free-market narrative. Economists like Milton Friedman love to emphasize the ‘free’ part of the free market. (Never one for subtly, Friedman drove the point home in a book called Capitalism and Freedom). The cultural evidence seems to be on Friedman’s side. As societies industrialize, they become more skeptical of autocratic power, and hence, more ‘freedom loving’. Point for the free-market narrative.

Cultural Tightness

Since Hofstede’s pioneering work in the 1970s, scientists have created many different measures of culture. Perhaps the most famous is psychologist Michele Gelfand’s distinction between ‘tight’ and ‘loose’ cultures. ‘Tight’ cultures, she proposes, have strong norms and a low tolerance of deviant behavior. ‘Loose’ cultures have weak norms and a high tolerance of deviant behavior.

Table 3 shows the questions Gelfand uses to gauge cultural tightness. Answering ‘yes’ to questions 1, 2, 3 or 5 and ‘no’ to question 4 indicate tighter culture. From these questions, Gelfand constructs a ‘tightness index’.

Source: Rule Makers, Rule Breakers

Source: Rule Makers, Rule Breakers

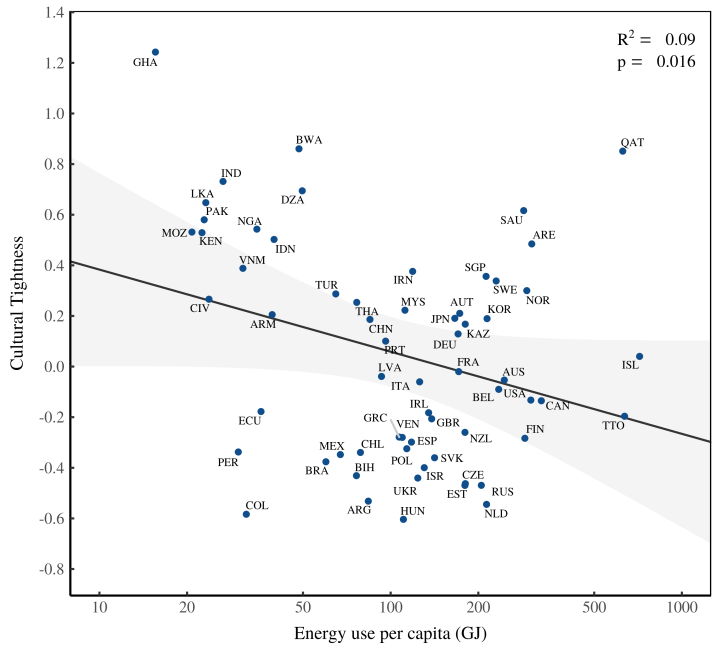

In Figure 3, I plot Gelfand’s index of cultural tightness against energy use per capita. As energy use increases, cultures tend to become ‘looser’, meaning they become less conformist and more tolerant of deviance. (Note, though, that the trend is weak.)

Our measurement of culture again seems to support the free-market narrative. Economists claim that competitive markets drive innovation. But this works only if people are receptive to new ideas. Apparently such openness tends to increase with industrialization. Point for the free-market narrative.

✹ ✹ ✹

Let’s summarize this foray into cultural measurement. Industrialization comes with a host of cultural changes — a fact that is unsurprising. It’s not our DNA that separates industrial humans from our ancient ancestors. It’s our ideas.

That being said, the direction of the cultural shift is somewhat surprising — especially to critics of mainstream economics (like me). The evidence points to a cultural shift towards individualism — exactly what economists say is required for free markets to work. But when viewed through an evolutionary lens, this cultural shift is odd. The problem is that in evolutionary terms, the interests of individuals rarely (if ever) align with the interest of the group. Your best option, as a selfish individual, isn’t to contribute to society. Your best option is to free ride. This means that the success of social species (like humans) depends crucially not on elevating self interest, but on suppressing it. (See Unto Others for an exposition.)

Contrary to what evolutionary theory claims we should do, humans seem to have industrialized not by suppressing self interest, but by stoking it. Does this mean evolutionary theory is wrong? Unlikely. The crucial point is that we’ve so far measured human ideas. But evolution cares only for actions. Now here’s the curious thing. When we measure human actions, we get a very different story than the one told by our ideas.

The disconnect between ideas and actions

Ideas are not the same as actions — a fact that the founders of the United States made clear. In crafting the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson heralded the unalienable rights of individuals:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Curiously, Jefferson wrote these words (which have become synonymous with human rights) while owning hundreds of slaves. Obviously Jefferson’s ideas were disconnected from his actions. This example illustrates a basic fact of life. Although we’d like to think that our actions align with our ideas, they need not.

This disconnect is important, especially if we want to ground the study of culture in evolutionary theory. In evolutionary terms, all that matters is what our ideas do (to our behavior). What we think they do is irrelevant. For this reason, evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson argues that belief systems are often ‘massively fictional’. Their claims about the world are different than their effect on behavior:

Groups governed by belief systems that internalize social control can be much more successful than groups that must rely on external forms of social control. For all of these (and probably other) reasons, we can expect many belief systems to be massively fictional in their portrayal of the world.

(David Sloan Wilson in Darwin’s Cathedral)

Having measured how ideas change with industrialization, let’s do the same with behavior. As you’ll see, doing so turns the free-market narrative on its head.

Narrative 2: Developing through hierarchy

Human behavior obviously has many dimensions. But here I’ll focus on just one: the tendency to organize using hierarchy. This tendency needn’t have a direction. But if it did, the cultural evidence suggests it should be downward. That’s because industrialization brings a shift towards individualism. With this shift, we’d expect societies to also become less hierarchical. But that’s not what happens. Instead, hierarchy actually increases.

There are many ways of looking at the growth of hierarchy, but perhaps the simplest is to count managers. That’s because the job of a manager is to control the activity of other people. It’s a job that, without hierarchy, couldn’t exist. So counting the relative number of managers gives a window into the extent of hierarchy.

When we count the number of managers (a measurement of human behavior), we get a very different story than the one told by the measurement of culture. With industrialization comes a trend towards more hierarchy (not less). Figure 4 tells the tale. As energy use per capita grows, so does the relative number of managers. True, this is indirect evidence for the growth of hierarchy. But with a little math, we can show that the trend in Figure 4 is exactly what we’d expect if hierarchy increases with energy use. (See Economic Development and the Death of the Free Market for details.)

In light of this growth of managers, our measurements of culture now seem paradoxical. At the very time that societies became more individualistic, hierarchy actually increased.

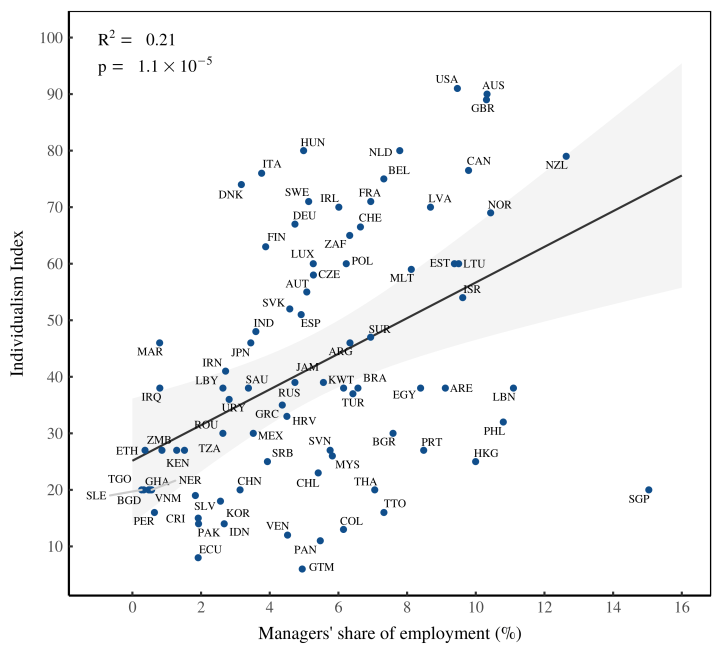

To drive this point home, let’s directly compare ideas and actions. We’ll plot our cultural metrics (ideas) against the managers’ share of employment (action). Figures 5 to 7 show the comparison, with fascinating results. Our cultural metrics correlate with the growth of managers — but in the wrong direction. As the relative number of managers grows:

- individualism increases (Figure 5)

- power distance decreases (Figure 6)

- culture becomes looser (Figure 7)

It seems that there is a mismatch between our ideas and our actions. When we measure ideas, we see a trend towards more individualism, more skepticism of power, and greater tolerance for deviance. Yet when we measure behavior, we see a trend towards more hierarchy. In other words, people claim to believe more in autonomy while at the same time living as subordinates within ever larger hierarchies.

This is the paradox of individualism and hierarchy.

Resolving the paradox

As a scientist, I live for a good paradox. Why? Because paradoxes signal an inconsistency in our knowledge that we must resolve. When we find a paradox, one of two things must be true:

- The evidence (that leads to the paradox) is wrong

- Our ideas are wrong

So which is the case here? Since empirical research is always uncertain, it’s possible that the evidence (above) is wrong. But let’s assume that the evidence is sound. This means that both individualism and hierarchy grow together. How can we resolve this paradox?

We’ll start by defining the concepts at work, beginning with autonomy. To be autonomous is to control your own actions. By extension, to lack autonomy is to lack control over your actions. Now let’s think about how humans lose autonomy. “Man is born free,” Rousseau famously noted, yet “everywhere he is found in chains”. The chains are (mostly) metaphorical. We lose our freedom by surrendering control of our actions to other people. In other words, by becoming subordinates.

The act of subordination is an intrinsic part of hierarchy. A hierarchy is a nested set of power relations between superiors and subordinates. Because of this element of subordination, it seems paradoxical that people could claim to believe more in individual autonomy while simultaneously working in ever larger hierarchies.

Diving a little deeper, though, and we realize that there needn’t be a paradox. The key is that our perception of the world is likely driven not by the larger social context, but by our interaction with specific people. In a hierarchy, our perception of autonomy is probably driven by interaction with direct superiors. Now here’s the crucial part. This interaction is largely independent of the size of the hierarchy in which we work. If you have a tyrannical boss, you’re going to feel subjugated … regardless of whether you work in a huge company like Walmart or a tiny mom-and-pop shop. So your perception of autonomy comes not from the size of the hierarchy in which you belong, but from the strength of the power relations within it.

This distinction is key. Our evidence for hierarchy (the growth of managers) measures the size of hierarchies. It says nothing about the strength of power relations within each hierarchy. Now, it seems intuitive that power relations might strengthen as hierarchies grow larger. But this need not be the case. In fact, it’s plausible that larger hierarchies actually have weaker power relations. If this is true, it means that people work in ever larger hierarchies while perceiving that they have more autonomy.

Sam Walton vs. Al Capone

To resolve the paradox of individualism and hierarchy, I’ll distinguish between two dimensions of power:

- the number of people you influence

- the strength of this influence (per person)

The transition to capitalism, I argue, is associated with a vast increase in the size of hierarchies. This means that the number of people influenced by elites has greatly increased. At the same time, the strength of influence per person has probably declined, meaning subordinates perceive that they are more autonomous.

To frame this distinction, consider the difference between Sam Walton and Al Capone. As one of the most notorious gangsters in history, Al Capone had near absolute control over his subordinates. (Disobeying Capone meant risking death.) So in Capone’s gang, power relations were strong and (perceived) autonomy was likely limited. Now contrast Al Capone with Sam Walton, the founder of the largest corporation that has ever existed (Walmart). Compared to Capone, Walton’s control over subordinates was quite loose. And yet despite this looseness (perhaps because of it), Sam Walton controlled far more subordinates than Capone ever did. Capone demanded exacting obedience from (at most) a few thousand gang members. Sam Walton, in contrast, demanded loose obedience from millions of Walmart employees.

I compare the capitalist Sam Walton to gangster Al Capone because mafia organizations like Capone’s are essentially relics of the past. They’re organized around family ties, with control over the hierarchy largely a function of lineage. This system of lineage-based organization is probably the default mode of human hierarchy. It’s common in simple chiefdoms. And it’s found in all feudal societies.

As a rule, lineage-based hierarchies constrict autonomy. By design, inherited status makes it difficult both to move between hierarchies and to advance within them. Take feudal serfs as an example. If a serf didn’t like his lot in life, he couldn’t just find another master. (Serfs were tied to their lord for life.) And it was impossible for serfs to become lords. So vertical mobility wasn’t an option.

The transition to capitalism did away with this suffocating system. In capitalist societies, power became vendible. This change likely meant that capitalist hierarchies became looser than their feudal counterparts. The stifling order of birthright gave way to a more dynamic order based on ownership. And so autonomy increased. (For a discussion of this transition, see Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler’s Capital as Power.)

From feudal clan to business firm

The transition to capitalism saw the demise of the feudal clan (based on the extended family) and the rise of the nuclear family. It’s a story of the break-up of collectivism and the rise of individualism. (Or so it seems.)

Looking at the spread of individualistic psychology, economic historian Jonathan Schulz and colleagues recently found that it was strongly linked to cousin marriage. The lower the rate of cousin marriage, the more individualistic people’s psychology. The reason for this connection, Schulz argues, is that cousin marriage was a potent way of unifying the extended family. So when people stopped marrying their cousins, the feudal clan dissolved into the modern nuclear family.

So why did people stop marrying their cousins? Schulz thinks it was because of the (Western) Catholic church. In the Middle Ages, Catholic priests became obsessed with incest, and eventually banned cousin marriage. The effect, Schulz proposes, was to kill the feudal clan and give rise to an individualistic worldview. It’s a tale of the death of collectivism and the rise of individualism. But this is only part of the story.

The other side of the story is that at the same time that the family unit shrank (and people became more individualistic), the family also ceased to be the unit of economic organization. The feudal clan was replaced by the business firm. And business firms grew larger than any feudal clan ever was. (Think Sam Walton versus Al Capone.) So people’s ideas became individualistic at the same time that their behavior became more collectivist.

The double-edged sword

Hierarchy and individualism grow together. That’s what the evidence tells us. I’ve so far tried to explain how this paradox can be resolved. I’ll conclude by going a step further. Might individualism be a prerequisite for large hierarchies?

Here’s why this may be true. Hierarchy is an organizational tool that comes with both benefits and costs. The benefit is that hierarchy is a potent way of organizing large groups. By concentrating power, hierarchical groups can act cohesively in ways that egalitarian groups cannot. (For details, see Peter Turchin’s book Ultrasociety.) This cohesiveness is a huge advantage in group competition. But it comes with a cost — namely despotism. When groups use hierarchy to organize, rulers inevitably use their power to enrich themselves. This despotism, in turn, undermines the benefits of hierarchy to the rest of the group. So to reap hierarchy’s benefits, groups must concentrate power without succumbing to despotism.

Perhaps individualism grows with hierarchy because this worldview is a tool for limiting despotism. This is speculative, but plausible. The idea is that if you believe in autonomy, you’ll tend to oppose despotism. In so doing, you’ll increase the benefits of hierarchy. The result, paradoxically, is that rather than destroy hierarchy, individualism actually feeds its growth.

If true, this story turns economic theory on its head. It means that enshrining the rights of individuals doesn’t lead to atomistic free markets. It leads to collectivist hierarchies. One has to marvel at the irony. By preaching the miracle of the market, neoclassical economists may have helped forge their own collectivist nightmare.

Sources and methods

Individualism and power distance

Data for the ‘individualism’ and ‘power distance’ indexes come from Geert Hofstede’s book Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. In addition to measures for specific countries, Hofstede reports measures for the following regions: (1) Arab countries; (2) East Africa; and (3) West Africa. Based on Hofstede’s notes, I disaggregate these regions as follows:

-

Arab countries = Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates

-

East Africa = Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia

-

West Africa = Ghana, Niger, Sierra Leone, Togo

I assign each country Hofstede’s metric for the region.

Cultural tightness

Data for cultural ‘tightness’ comes from Gelfand and colleague’s recent preprint The Importance of Cultural Tightness and Government Efficiency For Understanding COVID-19 Growth and Death Rates. You can download the data at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/pc4ef/

Energy

Data for energy use per capita comes from the World Bank, series EG.USE.PCAP.KG.OE. To these values I add an estimate for energy consumed through food (2000 kcal per day).

Managers

Data for managers’ share of employment comes from ILOSTAT, Table TEM_OCU, series EMPoc1P.

Matching data

Neither Hofstede’s nor Gelfand’s data come with measurement dates. Here’s how I match their measurements with energy and management data.

According to Hofstede, most of his data was gathered in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I match his reported metrics with energy data from 1970 (or the available year that is closest to 1970. Managers data begins in 1990. To match it with Hofstede’s metrics, I average the manager data over the whole period of available data.

Gelfand’s data was first reported in a 2010 paper. I assume that this was the date of data gathering. I match Gelfand’s data with energy use data in 2010 (or the available year closest to 2010). I match Gelfand’s data with the average of managers data over the period 1990-2010.

Notes

-

In their book Capital as Power, Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler put the Greek concept of the nomos at the center of their theory of capitalism. You cannot understand capitalism, they argue, without understanding the capitalist nomos. Nitzan and Bichler trace their thinking to Cornelius Castoriadis, who in turn, traces his thinking to Aristotle.↩

-

Hofstede created his individualism index using a factor analysis of IBM survey questions. On the individualist pole were people who ranked ‘free time’, ‘job freedom’, and ‘job challenge’ highly. On the collectivist pole were people who ranked ‘job training’, ‘physical conditions’, and ‘use of skills’ highly.

It’s not clear that this collectivist pole is the opposite of the individualistic pole. Rather than emphasize a lack of freedom or dependence on others, the collectivist pole seems to emphasize job conditions. There may be a hierarchy of needs at work here. When struggling to meet your material needs, you’re likely more concerned with job conditions than with personal freedom. But as your standard of living improves, you become concerned with a ‘higher’ set of needs.

Many people have raised this objection to Hofstede’s individualism index. Still, follow up research that uses more convincing questions to gauge ‘collectivism’ correlate strongly with Hofstede’s original work (see Gelfand et al., Minkov et al and Schulz et al.)↩

Further reading

Fix, B. (2017). Energy and institution size. PLOS ONE, 12(2), e0171823. https://doi.org/doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0171823

Fix, B. (2019a). An evolutionary theory of resource distribution. Real-World Economics Review, (90), 65–97. http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue90/Fix90.pdf

Fix, B. (2019b). Energy, hierarchy and the origin of inequality. PLOS ONE, 14(4), e0215692. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215692

Gelfand, M. J., Bhawuk, D. P., Nishii, L. H., & Bechtold, D. J. (2004). Individualism and collectivism. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies, 437–512.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61–83.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 2307–0919.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Minkov, M., Dutt, P., Schachner, M., Morales, O., Sanchez, C., Jandosova, J., … Mudd, B. (2017). A revision of Hofstede’s individualism-collectivism dimension. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management.

Nitzan, J., & Bichler, S. (2009). Capital as power: A study of order and creorder. New York: Routledge.

Schulz, J. F., Bahrami-Rad, D., Beauchamp, J. P., & Henrich, J. (2019). The church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation. Science, 366(6466).

Sober, E., & Wilson, D. S. (1999). Unto others: The evolution and psychology of unselfish behavior. Harvard University Press.

Turchin, P. (2016). Ultrasociety: How 10,000 years of war made humans the greatest cooperators on earth. Chaplin, Connecticut: Beresta Books.

Wilson, D. S. (2010). Darwin’s cathedral: Evolution, religion, and the nature of society. University of Chicago Press.