Deconstructing Econospeak

November 25, 2021

Originally published at Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

It’s been 20 years, but I still remember the feeling. It was a mix of curiosity and unease. I was curious because I was learning something new. But I was uneasy because something didn’t sit right. The place was Edmonton, Alberta, circa the year 2000. The situation? My first encounter with economics: Econ 101.

Interestingly, I can’t remember much of the course content. Instead, what I remember is the feeling. As I grappled with the language spoken by the economics textbook (what I’m calling econospeak), I felt that something was missing. But I couldn’t put my finger on what … and I was too busy to think much about it. So I ignored the feeling, memorized the course content, and moved on.

Today I’m a PhD-trained political economist and I know why I had a bad feeling in Economics 101. It’s because the course wasn’t teaching me about the real world. It was indoctrinating me in an ideology.

I’ve spent much of the last decade trying to understand this ideology. A key part of its appeal, I believe is the language that it uses. Of course, many people recognize that the language of econospeak is part of its ideological potency. And many people have analyzed this language. But what nobody has done (as far as I can tell) is to quantitatively deconstruct econospeak. That’s what I’m going to do here.

I’ve created a word-counting bot that compares the language found in economics textbooks to the English language at large. I’m going to use this bot to analyze econospeak. The results (which I’m only beginning to unwrap) are fascinating. Let’s dive in.

A word-counting bot

Before we get to the specifics of my word-counting bot, I’ll give it some context.

When someone asks you to ‘think critically’ about a text, they want you to compare what the author has said (or not said) to what other people have said. Here’s an example. When I read an economics textbook and see the words ‘rational utility maximizer’, I think of Thorstein Veblen’s phrase ‘homogenous globules of desire’ — a satire of the utility maximizing human. I also think of the novels I’ve read, and how the characters are filled with emotions — emotions that are absent from economics textbooks. In short, I compare the words in the economics textbook to everything else I’ve read.

This example illustrates why critical reading is difficult. To read critically, you have to read widely. The problem, though, is that there’s too much to read — far more than any human could digest. And that’s got me thinking. Is there a way to automate the act of critical reading?

Enter my word-counting bot. No, my bot is not an AI literary critic. It’s far simpler. My bot counts words. The idea is that the words you use (or don’t use) tell us about what you’re thinking. To ‘read critically’, we compare your vocabulary to the vocabulary of other people. We see how frequently you use certain words relative to everyone else. If, for instance, you have sex on your mind, you’ll likely use the word ‘sex’ more than other people. And conversely, you might use the word ‘love’ less than everyone else.

When we (as humans) read a text, we get an intuitive sense for what’s there and what’s not. But my word-counting bot can take this a step further. It can quantify word frequency … and it can do it on a massive scale.

Now let’s get to the specifics. My word-counting bot takes a sample of writing and quantifies the frequency of each word found in the text. It then compares this frequency to what’s found in the English language at large. The bot returns the ratio of the two frequencies — what I’m calling relative word frequency:

The bot can take any sample of text as an input. Here, I feed it undergraduate economics textbooks. From Library Genesis, I’ve downloaded 43 economics textbooks that are standard fare in economics pedagogy. (Details here.) I’ve fed these books to my bot, and it spits out the frequency of each word in the text.

To measure ‘word frequency in English’ I’ve used data from the Google books database. According to Google, this database is the world’s largest repository of full-text books. Conveniently, Google has created the Ngrams database, which reports word frequency in its books corpus. I use word frequency in the Ngram database (which I’m calling the ‘Google English corpus’) to represent ‘word frequency in English’. I will revert, at times, to calling this Google sample ‘average English’. That doesn’t mean it’s what the ‘average person’ speaks. It’s the average of a huge sample of English text.

To summarize, my word-counting bot eats economics textbooks and spits out relative word frequency, defined as:

In my sample of economics textbooks, there are about 34,000 unique words. My bot calculates relative frequency for all of them. But before we look at the whole output, let’s get a feel for the data. Table 1 shows the frequencies of four words found in the textbook sample.

Table 1: Examples of relative word frequency

| Word | Frequency in economics textbooks* | Frequency in Google English* | Relative frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| price | 13900 | 296 | 46.9 |

| science | 105 | 377 | 0.277 |

| murder | 3.65 | 81.8 | 0.0446 |

| ditchdigger | 0.13 | 0.015 | 8.71 |

| * Frequency = occurrence per million words | |||

The first thing to notice is that word frequency varies wildly. Economics textbooks use the word ‘price’ about 100,000 times more than they use the word ‘ditchdigger’. Now, for these specific words that frequency difference isn’t surprising. But the wild variation in word frequency is actually a feature of language in general. Some words (like ‘and’) get used a lot. Other words (like ‘mesonemertini’) are so rare that you’ve never heard of them.

This huge variation in word use is why looking at the absolute frequency of words in economics textbooks isn’t very useful. What matters is not absolute frequency, but relative frequency — word use relative to the average. And this relative frequency, it turns out, is not necessarily related to absolute frequency.

Table 1 illustrates this fact. Economists use the word ‘price’ a lot. And as you’d expect, they use it more than average — about 40 times more. Conversely, economists almost never use the word ‘ditchdigger’. You’d have to read about 10 million words of econospeak to see ‘ditchdigger’ once. And yet economists use the word ‘ditchdigger’ 9 times more than average. So even though ‘price’ and ‘ditchdigger’ have wildly different absolute frequencies, both are overused by economists.

Let’s continue. Economics textbooks use the word ‘science’ far more than the word ‘ditchdigger’. Yet it turns out that they’re using ‘science’ less than average. (Given economics’ pseudoscience state, I can’t help but laugh at this result.) And what about ‘murder’? Economics textbooks use it about 30 times more than ‘ditchdigger’. But this constitutes underuse. Economists use the word ‘murder’ 20 times less than average.

What’s important here is that a word’s absolute frequency (in economics textbooks) doesn’t predict its relative frequency. We’ll return to this fact later.

Now that you understand what my word-counting bot does, let’s dive into the data.

The ‘shape’ of econospeak

When we analyze language, most people are interested in the specific words that are used. (I will get to specific words, don’t worry.) The problem, though, is that my bot returns data for about 34,000 words. That’s far too many words to discuss individually. But what we can do is look at the ‘shape’ of these words. I’m calling this the ‘shape’ of econospeak.

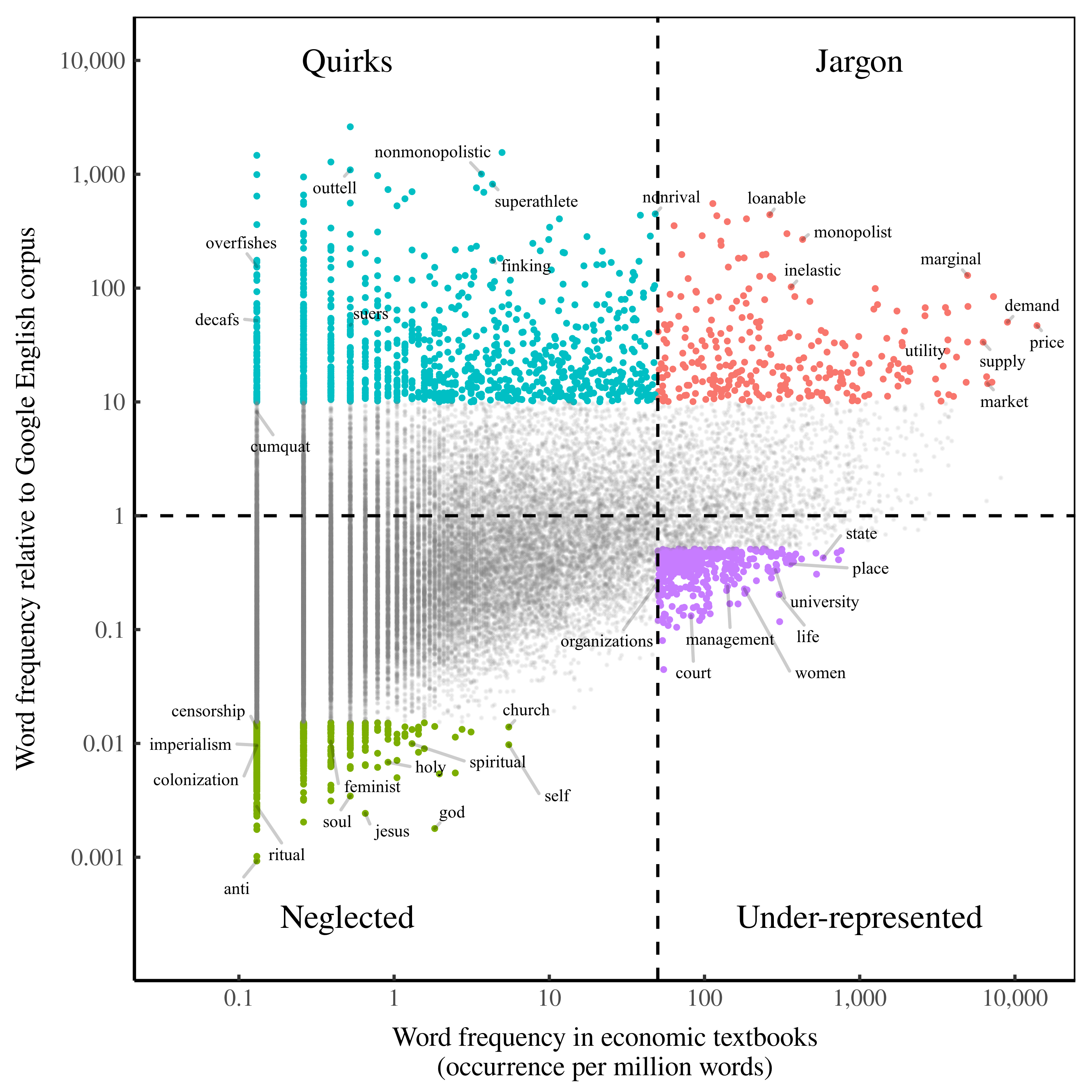

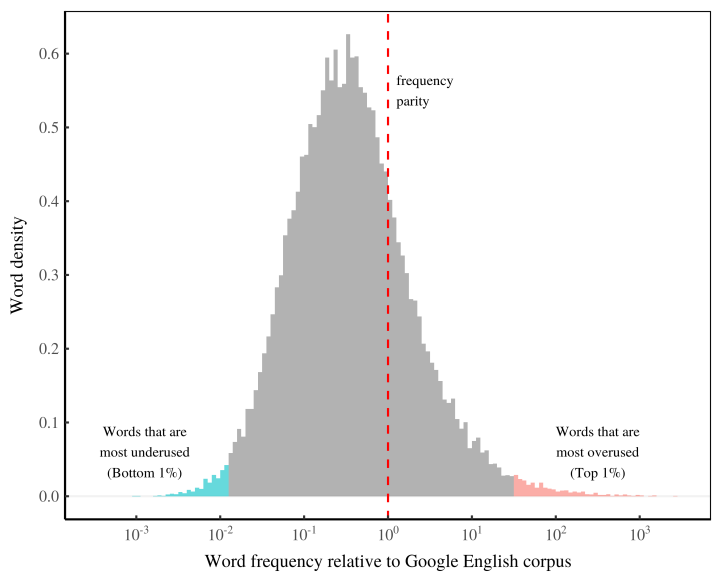

I’ve plotted this shape in Figure 1. Here I show the distribution of relative word frequency in economics textbooks. The horizontal axis shows the ratio of textbook frequency to Google frequency. (Note that I’ve used a log scale, so each tick mark indicates a factor of 10). The vertical axis shows ‘word density’ — the portion of words with the given relative frequency.

Let’s dissect this ‘shape’ of econospeak. We’ll start with the vertical red line that I call ‘frequency parity’. This line indicates that a word occurs at the same frequency in economics textbooks as it does in the Google corpus. (Its relative frequency is 1.) If the vocabulary in economics textbooks was identical to the vocabulary in the Google corpus, the distribution in Figure 1 would clump around the red line. But it doesn’t. That tells us that econospeak is different than average English. Hardly surprising.

Let’s talk about how econospeak is different. Notice that the peak of the econospeak distribution is to the left of frequency parity. That’s interesting. It suggests that economics textbooks use a large portion of English words less than average. I honestly didn’t expect this result, and am still trying to interpret it.

Here are two possibilities. First, the underuse of common English words could be a defining feature of econospeak. Alternatively, this underuse could be a feature of any branch of specialized writing. Either way, though, the result is important. It suggests that a key feature of econospeak is its underuse of a large chunk of the English language.

Let’s move on to the extremes of econospeak — the words that are most overused and most underused (relative to average English). These words live in the tails of the relative frequency distribution (shown in color in Figure 1). Notice that these tails are true extremes. In econospeak, some words are used 1000 times more than average. And other words are used 1000 times less than average.

I know you want to see these words. But before we get there, we need to do some statistics. Whenever we do empirical work, we need to make sure that our results aren’t caused by chance. We don’t want to get fooled by randomness. (Hat tip to Nassim Nicholas Taleb for this phrase). With randomness in mind, consider a thought experiment. Suppose that my econospeak data is actually a random sample of words taken from the Google English corpus. If this were true, what would the distribution of relative word frequency look like?

In statistics, this thought experiment is called the ‘null hypothesis’. To test the null hypothesis, we randomly draw words from the Google corpus and compare the result to our econospeak data. Figure 2 shows this comparison. Here, I’ve taken a random sample of 7.7 million words (the size of my econospeak sample) from the Google English corpus. For each randomly drawn word, I’ve calculated its frequency relative to the entire Google corpus. The red curve shows the resulting distribution of relative word frequency.

Let’s dissect this result. The null hypothesis has a huge peak around frequency parity. That means that most words in our random sample occur at the same frequency as in the Google corpus. That’s unsurprising. (We are, after all, sampling from the Google corpus.) What is surprising, though, is that our random sample produces about the same number of overused words as found in econospeak. To see this fact, look at the right tails of the distributions in Figure 2. The right tail of the null hypothesis is similar to the right tail of the econospeak distribution. Does this similarity mean that economists are randomly overusing words? Yes and no. As you’ll see shortly, there’s more to the story.

What’s most important, in Figure 2, is not word overuse, but word underuse. Looking at the two distributions, we see that the left tail of the econospeak distribution far outreaches the left tail of the random sample. This tells us that econospeak’s underuse of many English words cannot be due to chance.

This result is fascinating, and I’ll return to it throughout the post. It suggests that econospeak is defined not by what it says, but by what it doesn’t say.

The most overused and underused words in econospeak

Now that we’ve looked at the ‘shape’ of econospeak, let’s get more concrete. Let’s look at the words that economics textbooks most overuse and most underuse. The results will surprise you.

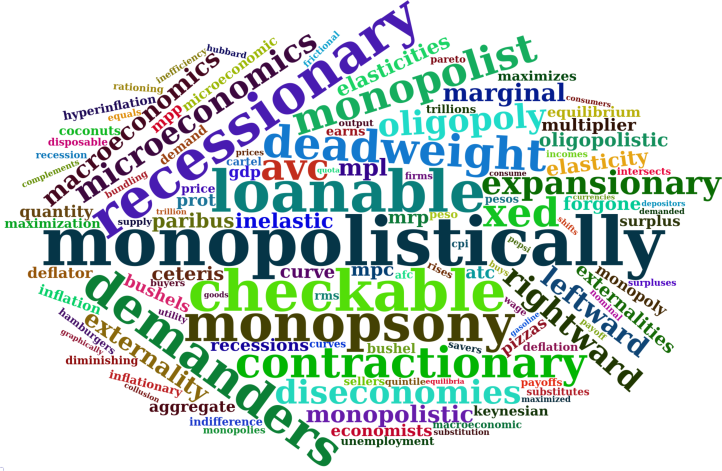

We’ll start with the words that economics textbooks most overuse relative to average English. Figure 3 shows these words in a cloud. The larger the font, the more the word is overused.

If you’ve ever read an economics textbook, the words in Figure 3 are not what you’d expect. You’d think that the most overused words would be economics jargon — terms like ‘supply’, ‘demand’ and ‘market’. And yet this jargon is nowhere to be found. Instead, Figure 3 shows a collection of bizarre words. (‘Grasshopperish’ … seriously?) What’s going on here?

I’ll be honest. I didn’t anticipate that the most overused words in econospeak would be oddballs. But I understand (now) how it happens. Our intuition is that we overuse words by writing them many times. But this is only one path to overuse. The other path is to pick an extremely rare word and use it a few times. It’s this other path to overuse that explains why Figure 3 is filled with oddballs.

Take the word ‘outtell’. In the Google corpus, it appears once every 10 billion words. That’s so rare that you’d likely not see it in a lifetime of reading. The word ‘outtell’ is also rare in econospeak. It occurs just 4 times in my sample of textbooks. But that’s enough to constitute massive overuse. The same is true for many of the words in Figure 3. They’re rare words that got used a few times by economists.

Not all the words in Figure 3, however, are oddballs. Some of them are recognizable jargon (for instance, ‘loanable’, ‘monopolist’ and ‘oligopoly’). How do we distinguish this jargon from the quirks? We’ll get there shortly.

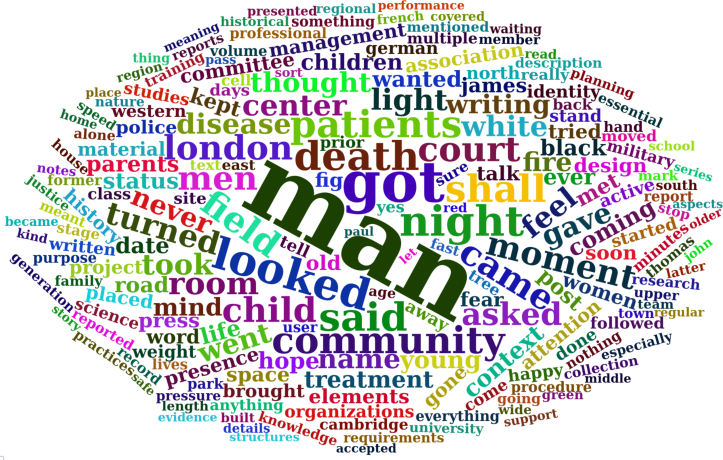

First, though, let’s look at the most underused words in econospeak. Figure 4 shows these words. Here, a larger font indicates that the word is more underused.

I could write an essay about the words in Figure 4. But I have other results to show you, so I’ll reflect on just a few of the words.

First, it seems that econospeak underuses many religious words (for instance, ‘jewish’, ‘jesus’, ‘god’, ‘gospel’, ‘islam’, ‘ritual’, etc.). This underuse is in some ways banal. We can think of English writing as having two sides — a secular side and a religious side. Secular writing will tend to underuse religious words. And religious writing will tend to underuse secular words. So what we’re seeing, in Figure 4, is that econospeak is secular. That’s no surprise.

Economics textbooks, however, are a very particular type of secular writing. They’re promoting a secular ideology. And that makes economists’ underuse of religious words more interesting. Framed this way, we can think of Figure 4 as showing two contrasting ideologies. The secular ideology of economics largely excludes the language used by religious ideologies. Fascinating.

Let’s move on to another important result. The most underused word in econospeak is … drum roll please … ‘anti’!

I didn’t expect this result. (Did you?) But I’ve had a few weeks to think about it, and I’ve realized that it’s quite revealing. Here’s why. The word ‘anti’ offers a succinct way of saying you’re opposed to something. As in:

Bob is anti slavery.

The near total absence of this word in economics textbooks speaks volumes about economics ideology. If you talk in econospeak, it’s difficult to voice opposition. That’s because economists frame opinions in terms of ‘preferences’. As in:

Bob has a preference for Cheerios.

Such banal opinions litter economic textbooks. What about more serious opinions? If you talk like an economist, it’s easy to voice support for something. For instance:

Bob has a preference for slavery.

But how do you use the language of ‘preferences’ to voice opposition? You must resort to a torturous double negative:

Bob has a preference for not having slavery.

Such indirect language, you’ll notice, defangs Bob’s opposition. Compare the turgid sentence above to the simple alternative:

Bob is anti slavery.

Now Bob’s opposition is clear. And that’s why it’s so revealing that econospeak almost never uses the word ‘anti’. Economic textbooks are selling an ideology that legitimizes the status quo. And the best way to do that is to mute any talk of opposition. Purge ‘anti’ from your vocabulary.

Quadrants of econospeak

Now that we’ve looked at the most overused and underused words in econospeak, let’s look again at the big picture. The most overused words tended to be oddballs (Figure 3). How do we separate these quirks from more common economic jargon?

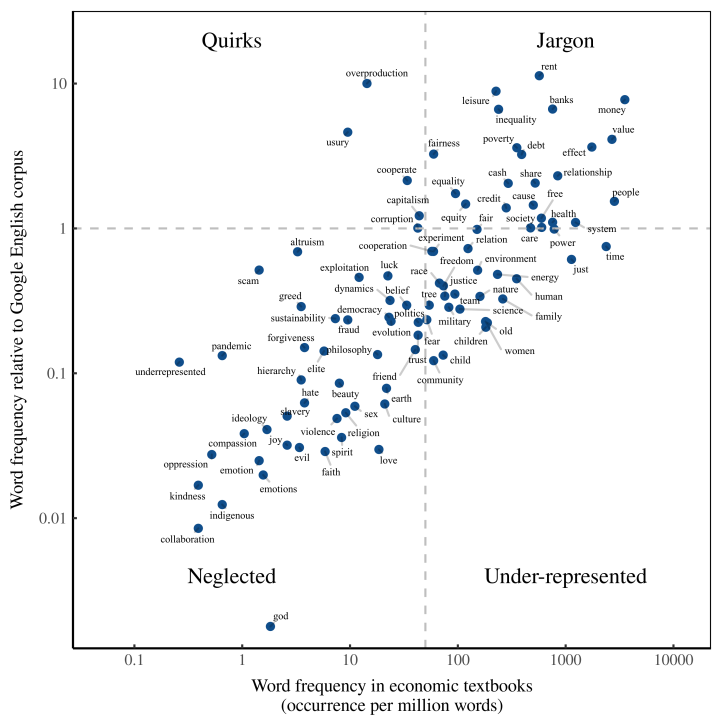

Figure 5 shows one way to do so. Here I’ve divided econospeak into four quadrants. Before we talk about each quadrant, let’s discuss the whole chart. In Figure 5, each point is a word. The horizontal axis shows the word’s frequency in economics textbooks. The vertical axis shows the word’s frequency relative to the Google corpus.

Now to the quadrants. What’s important about the quadrants is that they identify different types of overuse and underuse. ‘Quirks’ and ‘jargon’ are both overused relative to the Google corpus. But they take different paths. ‘Jargon’ is used frequently in economic textbooks. But ‘quirks’ appear rarely. (I’ve used 50 occurrences per million words as the dividing line between quirks and jargon.)

Let’s start with ‘jargon’. You can see, in Figure 5, that the ‘jargon’ quadrant contains familiar words like ‘price’, ‘market’ and ‘demand’. These are among the most common words in econospeak. And they’re overused relative to the Google corpus. That’s not surprising.

Now to the ‘quirks’ quadrant. This is where the oddballs live. Sure, there are some jargony words here (like nonmonopolistic). But the further left we go, the odder the words become (i.e. ‘cumquat’). These quirks are rare in economics textbooks, and yet still overused relative to the Google corpus.

Now to the different types of underuse. The ‘under-represented’ quadrant contains words that are used frequently in economics textbooks, but are still under-represented relative to the Google corpus. Here you’ll find many words related to social groups and human institutions. (More on this later.)

Last, we have the ‘neglected’ quadrant. These are words that economists use rarely. But unlike ‘quirks’ (which are rare outside of economics), ‘neglected’ words are common in average English. So in the ‘neglected’ quadrant, we find words that are massively underused. This quadrant is a goldmine for economics critics. If something is missing from economic theory, its vocabulary is probably in the ‘neglected’ quadrant.

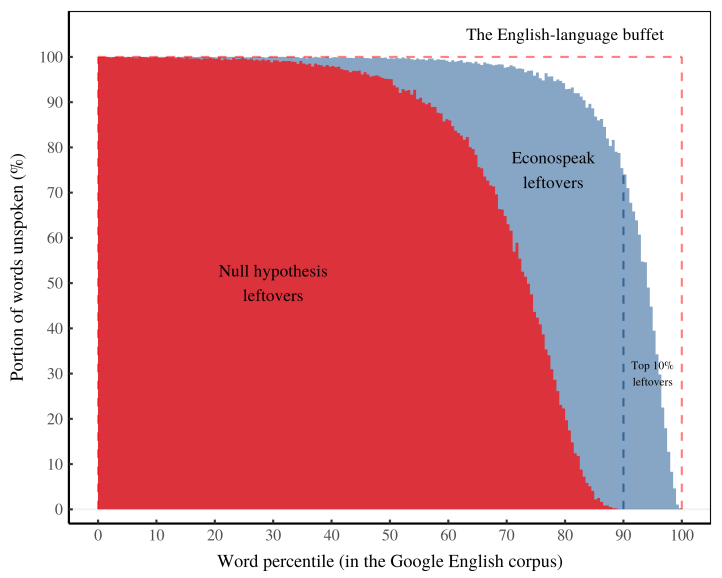

I know you want to see more of the words in each quadrant. (Skip ahead if you’d like.) But first we need to do more statistics. Let’s again compare econospeak to the ‘null hypothesis’. The null hypothesis, to remind you, is what happens when we randomly draw words from the Google corpus. Figure 6 shows how econospeak stacks up against this random sample. Again, each point is a word. Blue points are econospeak. Red points are the null hypothesis.

Here’s what the null hypothesis tells us. Many econospeak ‘quirks’, it seems, can be chalked up to chance. We know this because in the ‘quirks’ quadrant, many of the red dots (the null hypothesis) overlap blue dots (econospeak). This means we shouldn’t make too much of economists’ overuse of words like ‘cumquat’ and ‘decafs’. It’s probably just a matter of chance.

What’s important, though, is that all the other forms of overuse/underuse cannot be caused by chance. The null hypothesis does not create jargon. Nor does it create under-represented words, or extremely neglected ones. So in statistical terms, econospeak is significantly different than average English. Of course, if you’ve ever read an economics textbook, you already knew that. But here’s a quantification of your intuition.

Econospeak Jargon

Let’s get concrete again and talk about actual econospeak words. Figure 7 shows the top econospeak jargon. These are the words in the ‘jargon’ quadrant that are the most overused relative to average English. There aren’t many surprises here — just typical econospeak jargon.

Let’s use some of this jargon to make a paragraph of econospeak:

The loanable funds staved off deadweight losses, brought on by firms acting monopolistically. Demanders, however, were not aware of the diseconomies of scale that caused recessionary trends away from equilibrium. But microeconomists knew that, ceteris paribus, prices were not respecting mpl or mpc. So they ate bushels of inelastic pizza.

(jargon in bold)

OK, you’re unlikely to find such turgid writing in an undergraduate economics textbook. But this sentence is a fitting parody of the neoclassical economics literature. To the outsider, it’s incomprehensible gibberish. Actually, neoclassical economics is gibberish. The point of the jargon is to stop you from figuring that out.

Econospeak Quirks

Now to the top econospeak ‘quirks’, shown in Figure 8. These are words that economists use rarely, but still overuse relative to average English. Here, a larger font means that the word is more overused.

Unlike ‘jargon’, ‘quirks’ don’t jump out when you read economics literature. In fact, many of them are unique to a single textbook — they’re a quirk of a particular author. Lots of quirks result from non-hyphenation of usually hyphenated words. Some quirks may be typos. And a few of them, I’ll admit, could be an artifact of my word-counting bot. To analyze the textbooks, the bot converts PDF files to text files. The conversion isn’t perfect, and can introduce random errors. These show up in the ‘quirks’ quadrant.

Of the four quadrants of econospeak, ‘quirks’ are the least important, so I won’t analyze them much. Still, let’s try out a quirky paragraph:

Despite their grasshopperish legs, the superathletes tended to be homebodies. Their frontierlike, nondepreciating overdiscounting led to an underofficial refrainer.

(quirks in bold)

This paragraph has the flavor of econospeak. But the quirks are mostly just oddballs. I won’t pay much attention to them here.

Under-represented in econospeak

Now we’re getting to the meat of the analysis. What’s most interesting about econospeak is not what it includes, but what it excludes. Economics textbooks underuse a large portion of the English language. Let’s have a look at this underuse.

We’ll start with the ‘under-represented’ quadrant. These are words that are used frequently in economics textbooks, but still less than in average English. Figure 9 shows the most under-represented words. Here, a larger font indicates more underuse.

Let’s write a sentence with some of these words. Unlike before, though, this sentence won’t be a parody of what economists say. It will capture what they don’t say. Here’s try number one:

Before his death, the man went to court. His child asked about the fire … but he looked away. Hope had no purpose.

(under-represented words in bold)

This is a sentence you’d expect in a novel. It’s personal. It deals with a life or death situation. And it has emotion. These are things that econospeak tends to exclude.

Here’s try number two:

The woman’s status in the committee was a matter of history. The commission on professional organizations had decided that evidence-based administration was essential.

(under-represented words in bold)

This sentence picks out bureaucratic language. The fact that such talk is under-represented in economics is telling. Economists pays attention to competition between groups, but not to the bureaucratic dynamics within groups.

Neglected by econospeak

Let’s now look at words that are neglected by econospeak. These are words that economists almost never use — and this rarity constitutes massive underuse relative to average English. Figure 10 shows the most neglected words. The larger the font, the more the word is neglected.

I’ll try my hand at a paragraph with these words:

The Jewish man was anti Islam. He believed he was God’s servant. His submission to the scriptures was based on his counselor’s teachings. God was his commander and savior. This was his eternal ritual.

(neglected words in bold)

What we get, when we use these neglected words, is religous speak. If we treat mainstream economics as a science, then this result isn’t very surprising. It would be astonishing to find a science textbook that read like the Bible. But mainstream economics is not a science. It is an ideology. And so the fact that this ideology neglects religion is important. It highlights that there are two competing ideologies here.

There are many other neglected words (in Figure 10) worth discussing. But I have more results to show you, so onward.

Not speaking about power

The purpose of an ideology is, in large part, to legitimize the powers that be. In this regard, the ideology of economics is a bit odd.

Most ideologies legitimize power explicitly. They effectively say ‘this person is powerful, and you should obey their command’. Take, as an example, feudal ideology (i.e. religion). Feudal rulers boasted openly about their power, proclaiming that it stemmed from God. It’s no surprise, then, that religion is laced with terms like ‘commandments’ and ‘submission’. The devotion to justifying power is overt.

With economics, though, things are different. Economists don’t overtly praise the powerful. Instead they hardly talk about power at all. That leads some people to conclude that economics isn’t an ideology. But that’s a mistake. Economics is an ideology, but it wraps its justification for power under a pretense — namely ‘freedom’. In capitalism, corporate rulers don’t have the ‘power’ to command. They have the ‘freedom’ to command.

I’ve written about this subterfuge in The Free Market as a Double Lie. I showed how free-market speak became more popular at the same time that corporate power became more concentrated. If you take free-market speak literally, this trend makes no sense. But if free-market speak is subterfuge for justifying power, then the pieces fit together.

Here I want to look at the flip side of the equation — not speaking about power. What defines econospeak is that power is conspicuously absent. It’s a linguistic turn that George Orwell noticed almost a century ago. Politicians of the time, Orwell observed, had started to speak in torturous euphemisms. When militaries committed massacres, politicians call it pacification. Today, we’re so used to this euphemistic language that we hardly notice it. What we would notice is if a politician spoke plainly. Imagine a politician proclaiming:

Let the slaughter begin! The sons of this king will die because of their ancestors’ sins. None of them will ever rule the earth or cover it with cities.

This morbid passage, if you’re wondering, is from the Old Testament. It’s the ‘Good News’ translation of Isaiah 14:20. Surrounded by the euphemisms of modernity, we forget that people ever spoke so plainly. They did so, presumably, because the justification for power was overt. God was on their side.

Today, God is (mostly) off table. And that means power is justified through subterfuge. Instead of praising power, you leave it unsaid. As the dominant secular ideology, economics reflects this subterfuge. In economics, talk about power is conspicuously absent.

If you’re a good critical reader, you can notice this absence. But here I’ll go a step further and quantify it. I’ve gone through the thesaurus and picked words that relate to wielding and submitting to power. Figure 11 shows their frequency in econospeak.

The results, in Figure 11, are fascinating. The majority of words about power fall in the neglected quadrant. This speaks volumes about economics ideology. Economists don’t talk openly about power. That would ruin the subterfuge.

In simpler times, rulers boasted of their power. British imperialists, for instance, celebrated openly as they conquered the world. (For them, ‘imperialism’ was a good word.) But today, rulers talk in econospeak euphemisms. It’s not imperialism … it’s ‘free trade’!

Missing from econospeak

So far we’ve discussed words that are overused in econospeak, and words that are underused. Now let’s talk about words that are absent.

My sample of econospeak contains about 7.7 million words. In such a large sample, it’s no small feat for a word to be missing entirely. Unless the word is utterly obscure, its absence is important.

So what words are missing from econospeak? Many, obviously. But to frame the question, ask yourself — what is the most popular English word that economists don’t utter?

I’ve asked people on Twitter to take a guess. (See the responses here, here and here.) I’ve plotted these guesses in Figure 12. Notice that this is plot of words that are present in econospeak. That’s because almost no one managed to guess an actual missing word. Instead, the Twitterati were good at guessing neglected and under-represented words.

As with many of the plots in this post, I could write an essay about the words in Figure 12. But I have more results to show you. So let’s move on.

Let’s talk about the words that are actually missing from economics textbooks. I know you want to see the words themselves. (Skip ahead if you want.) But I first want to look at the structure of these missing words.

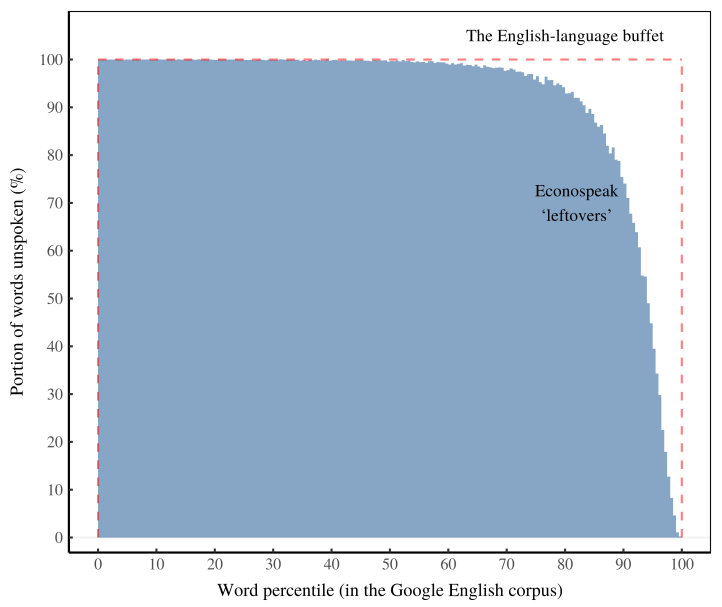

To understand this structure, it helps to have an analogy. Let’s think of the English language as a fully stocked buffet. The different foods represent words. Eating a food represents speaking a word. What we’re interested in here are the leftovers. These are the words that remain unspoken after economists finish talking.

Figure 13 shows one way of visualizing these ‘uneaten’ words. We start with the ‘English-language buffet’ (the red box). These are all the words in the English language (or in this case, a list of about 430,000 words from the Google English corpus). Before you’ve spoken anything, the language buffet is a square. The horizontal axis shows a word’s popularity, as indicated by its percentile in the Google corpus. The vertical axis is the portion of these words that you haven’t used.

Before you talk, the unused portion is 100% everywhere (you haven’t said anything). As you ‘speak’, you eat away at the buffet. If you speak in obscure prose, you eat away at the left side of the buffet. If you use only common words, you eat away at the right side.

What we’re interested in here are economists’ leftovers. When they speak (by writing textbooks), what words do they leave behind? Figure 13 shows the structure of these econospeak leftovers.

According to Figure 13, economics textbooks leave behind most of the English language — almost everything in the bottom 80% of words. The question is — what does this mean?

To interpret the econospeak leftovers, we’ll turn again to the ‘null hypothesis’. Recall that this is what happens when we randomly draw 7.7 million words from the Google corpus. Here, we’ll look at what the null hypothesis leaves behind. Figure 14 shows how the null hypothesis leftovers compare to what economists leave unspoken.

Like econospeak, the null hypothesis leaves behind most of the English language. (The bottom 70% of words remain largely unused.) So the fact that economists don’t use obscure words is unremarkable. It’s a basic feature of language. What makes words obscure, after all, is that few people use them.

There is, however, an important difference between econospeak and the null hypothesis. Econospeak leaves behind many popular words found in the top 10%. In contrast, the null-hypothesis leaves behind virtually none of these top words. So the fact that economists leave many popular words unspoken is statistically significant. (That said, it’s not clear if this is a distinguishing feature of econospeak, or if it’s found in all types of specialized writing. Figuring that out will take more digging.)

Let’s have a look at econospeak’s top 10% leftovers. Figure 15 zooms in on this part of the distribution. The histogram shows the shape of some 16,000 words that economics textbooks omit. That’s far too many words to discuss. But to give you a sense for what words are there, I’ve labelled some examples (of my choosing). These words appear at their corresponding percentile in the Google corpus. (Their vertical position doesn’t mean anything — it’s purely aesthetic.)

From the examples in Figure 15, I think you’ll agree that there are many important words that economists don’t utter. And what the statistics tell us is that this non-utterance is a choice. It cannot be chalked up to chance.

What’s interesting — and worth looking at more rigorously — is the absence of words about conflict. I’ve shown some of these words in Figure 15. (I’m sure there are many others.) It seems that economists don’t speak about ‘racism’, ‘defiance’, ‘patriarchy’, ‘treachery’, ‘sexism’, or ‘dispossession’. The absence of these conflict words is fascinating. Far from being random, I believe it’s a core part of economics ideology. Economics legitimizes power relations by pretending they don’t exist.

The top missing words

Now to the results that many of you have been waiting for. Let’s look at the most popular English words that are missing from economics. Figure 16 shows these words. The larger the font, the more popular the word.

The most popular word that’s absent from economics is … ‘Christ’. That’s an interesting result. But it says more about culture outside of economics than it does about econospeak. Economics is a secular ideology, so it’s no surprise that the last name of a Christian prophet goes unmentioned. What’s interesting is that outside of economics, the word ‘Christ’ is hugely popular. Again, this is a sign of religion’s lasting influence. In capitalist societies, religion may not be the dominant ideology, but its influence remains significant. (It’s informative that no one in my Twitter circle guessed the word ‘Christ’. It suggests that I live in a bubble of atheists.)

There’s much to be said about the other words in Figure 16. But I’ll conclude with just one observation — a fitting irony. We can use words that are absent from econospeak to describe economics ideology:

Economists are the high priests of capitalist society who worship at the altar of the free market. But their doctrines are not based on evidence. Instead, economics is a type of secular theology based on scripture.

(absent words in bold)

Ideology as the unsaid

I started this word-counting project after skimming Gregory Mankiw’s textbook Principles of Economics. I noticed that he used the word ‘distort’ a lot. Peppered throughout his book were whoppers like this:

Almost all taxes distort incentives, cause people to alter their behavior, and lead to a less efficient allocation of the economy’s resources.

(Mankiw in Principles of Economics)

Mankiw’s love for the word ‘distort’ got me thinking — how much does he use this word compared to the average? And so my word-counting bot was born. My initial focus was on the words that were overused. This overuse, I thought, would quantify economics ideology. (FYI: Mankiw does say ‘distort’ a lot. He uses it about 50 times more frequently than average.)

As I started to crunch the numbers, though, I realized that what is most interesting about econospeak isn’t what is overused. What’s interesting are the words that are underused or left unsaid. It’s this (relative) absence, I now believe, that’s key to understanding the ideology of economics.

It reminds me of George Lakoff’s book Don’t Think of an Elephant! If you want somebody to not think about something, the last thing you should do is tell them so. (You’re thinking of an elephant, aren’t you?) Herein lies the genius of economics ideology. Its purpose is to legitimize the status quo. It does so by getting you to think about a free-market fairy tale. While that’s got your attention, you don’t notice that power (and its many injustices) aren’t discussed.

To deconstruct economics ideology, in turn, entails talking about these absences. That’s difficult. What’s in a text is obvious. What’s not there is harder to see. Hence my unease when I took Economics 101. My gut was telling me that something was missing. But exactly what eluded me. Now I know. … because I ran the numbers. The data shouts loud and clear that a large part of the English language is absent from economics textbooks. It’s ideology through the unsaid.

Download the econospeak data and code

I know that many of you want to explore my econospeak data. To quench your thirst, I’ve included lists of the top 500 overused, underused, and missing words. See them here. I’ve also provided links (below) to my whole econospeak dataset. Lastly, I’m going to make an interactive chart that let’s you explore the structure of econospeak. Stay tuned for that.

Sources and methods

Economics textbooks

Table 2 shows my sample of economics textbooks. Although not exhaustive, this sample contains most of the standard textbooks used in undergraduate economics courses. When creating the sample, my restriction was that the textbooks should be published within roughly the same decade (here, 2004–2014) and that the books are available on Library Genesis. When possible, I tried to get the ‘micro’, ‘macro’ and ‘general’ versions of each book.

The resulting sample of econospeak contains about 7.7 million words, with a vocabulary of roughly 34,000 words.

Table 2: The sample of economics textbooks

| Author | Title | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Arnold | Economics | 2008 |

| Arnold | Macroeconomics | 2008 |

| Arnold | Microeconomics | 2011 |

| Blanchard & Johnson | Macroeconomics | 2012 |

| Case, Fair & Oster | Principles of Microeconomics | 2008 |

| Case, Fair & Oster | Principles of Macroeconomics | 2011 |

| Case, Fair & Oster | Principles of Economics | 2012 |

| Cowen & Tabarrok | Modern Principles of Economics | 2011 |

| Frank & Bernanke | Principles of Economics | 2008 |

| Frank & Bernanke | Principles of Macroeconomics | 2008 |

| Frank & Bernanke | Principles of Microeconomics | 2008 |

| Hubbard & O’Brien | Economics | 2009 |

| Hubbard & O’Brien | Macroeconomics | 2011 |

| Hubbard & O’Brien | Microeconomics | 2013 |

| Krugman & Wells | Macroeconomics | 2005 |

| Krugman & Wells | Economics | 2009 |

| Krugman & Wells | Microeconomics | 2012 |

| LeRoy Miller | Economics Today: The Macro View | 2011 |

| LeRoy Miller | Economics Today: The Micro View | 2011 |

| LeRoy Miller | Economics Today | 2011 |

| Mankiw | Principles of Economics | 2008 |

| Mankiw | Principles of Macroeconomics | 2011 |

| Mankiw | Principles of Microeconomics | 2011 |

| McConnell, Brue & Flynn | Macroeconomics | 2006 |

| McConnell, Brue & Flynn | Economics | 2008 |

| McConnell, Brue & Flynn | Microeconomics | 2011 |

| Nicholson & Snyder | Microeconomic Theory | 2004 |

| Nicholson & Snyder | Microeconomic Theory | 2007 |

| Nicholson & Snyder | Microeconomic Theory | 2011 |

| Parkin | Microeconomics | 2011 |

| Parkin | Macroeconomics | 2011 |

| Parkin, Powell & Matthews | Economics | 2005 |

| Perloff | Microeconomics | 2011 |

| Perloff | Microeconomics | 2014 |

| Pindyck & Rubinfeld | Microeconomics | 2012 |

| Pindyck & Rubinfeld | Microeconomics | 2014 |

| Rittenberg & Tregarthen | Principles of Economics | 2009 |

| Rittenberg & Tregarthen | Principles of Microeconomics | 2009 |

| Rittenberg & Tregarthen | Principles of Macroeconomics | 2009 |

| Samuelson & Nordhaus | Economics | 2009 |

| Varian | Intermediate Microeconomics | 2005 |

| Varian | Intermediate Microeconomics | 2010 |

| Varian | Intermediate Microeconomics | 2014 |

Notes: I downloaded the textbooks as PDFs and extracted the text using the Linux function pdftotext. This conversion can sometimes induce errors (often due to non-standard fonts). It’s possible that some of the quirks in econospeak are caused by faults in the PDF-to-text conversion.

Google English corpus

I’ve used Google’s 2020 1-gram corpus, which measures the text frequency of one-word phrases in the Google Books database. You can download the data here. (Warning: the 1-gram dataset is about 46 GB).

If you’re interested in working with Ngram data, I’ve written a post about my data-wrangling experience. I’ve also written some custom R code for importing Ngram 2020 data. It’s available at Github.

I use Ngram data over the years covered by the textbooks (2004-2014). For each word, I calculated its mean frequency over these years, weighted by the portion of the textbook sample published in each year.

Dictionary

I restrict both the econospeak sample and Google English sample to words that are in a predetermined ‘dictionary’. My dictionary consists of the following:

- The Grady Augmented word list from the R lexicon package

- The Project Gutenberg word list from Moby Word II

- An English word list from Leah Alpert

From this word list I remove/change the following:

- remove words with fewer than 3 letters

- remove common first names (using R

lexiconfunctionfreq_first_names) - remove common last names (using R

lexiconfunctionfreq_last_names) - remove prepositions (using R

lexiconfunctionpos_preposition) - remove English numerals from 1 to 100 (i.e. one, two, three …)

- remove ‘stop words’ (using R

tmcommandstopwords) - change British spellings to American (as in labour → labor)

- convert all words to lower case

- remove acronyms (words containing ‘.’)

- remove contractions (words containing apostrophes)

- remove hyphenated words

- remove words containing numbers 0-9

The resulting ‘dictionary’ contains about 500,000 words.

Econospeak word lists

Browse the top 500 overused, underused and missing words:

Top 500 overused words

| Word | Frequency relative to Google corpus |

|---|---|

| nondissipated | 2612.5 |

| latinian | 1553.0 |

| instrengthen | 1466.1 |

| refrainer | 1281.9 |

| outtell | 1093.2 |

| nonmonopolistic | 1003.8 |

| unleads | 993.1 |

| reisted | 973.0 |

| underofficial | 947.1 |

| superathlete | 819.3 |

| inpayments | 760.0 |

| pretariff | 734.2 |

| outpayment | 703.2 |

| willingnesses | 694.3 |

| inworked | 656.9 |

| reveto | 642.9 |

| debitable | 609.0 |

| idahoes | 573.1 |

| condimented | 558.4 |

| monopolistically | 552.9 |

| grasshopperish | 545.0 |

| nondepreciating | 528.0 |

| nonrival | 448.4 |

| loanable | 441.2 |

| monopsonist | 436.7 |

| checkable | 431.9 |

| recessionary | 406.0 |

| srac | 405.7 |

| overdiscounting | 384.1 |

| monopsony | 383.4 |

| msbus | 361.3 |

| demanders | 353.2 |

| upsloping | 342.5 |

| dissaved | 337.0 |

| underproduces | 311.1 |

| theftproof | 303.4 |

| deadweight | 300.7 |

| kinetophonograph | 297.0 |

| yuckers | 290.9 |

| contractionary | 288.4 |

| macroeconomists | 286.4 |

| oligopolist | 283.4 |

| monopolist | 267.6 |

| mobilia | 267.1 |

| xed | 258.9 |

| groland | 257.4 |

| macroeconomist | 247.2 |

| avc | 237.5 |

| monopsonies | 233.4 |

| undersupplies | 232.4 |

| superstrain | 225.8 |

| slumpflation | 223.7 |

| noncollusive | 222.9 |

| nonrecession | 222.1 |

| nonsatiation | 216.8 |

| superathletes | 216.1 |

| oversale | 214.6 |

| hyperinflations | 212.6 |

| mrts | 210.8 |

| overallocation | 206.0 |

| dissaving | 203.9 |

| overprovide | 202.8 |

| oligopoly | 198.3 |

| diseconomies | 197.1 |

| expansionary | 195.8 |

| equiproportional | 191.7 |

| rightward | 184.3 |

| frictionally | 183.0 |

| microeconomics | 182.9 |

| nonprohibitive | 179.5 |

| repaves | 178.2 |

| restep | 175.7 |

| pfennings | 175.1 |

| finking | 175.1 |

| longrun | 171.9 |

| nonstrategically | 170.4 |

| regovernment | 169.0 |

| snowboards | 168.0 |

| ditchdigging | 164.2 |

| homothetic | 161.2 |

| inpayment | 161.0 |

| nonlabor | 160.5 |

| gardol | 157.7 |

| nonunionized | 156.9 |

| overfishes | 154.5 |

| leftward | 153.0 |

| debudded | 152.8 |

| ploughwright | 152.4 |

| underproduce | 152.1 |

| traylike | 144.5 |

| monopsonistic | 144.4 |

| duopolist | 140.8 |

| nairu | 137.4 |

| dissaves | 135.4 |

| monetarists | 134.9 |

| shlu | 131.3 |

| bananaland | 130.9 |

| marginal | 129.2 |

| overprovision | 129.0 |

| misestimating | 128.4 |

| oligopolies | 128.4 |

| noncredibility | 127.6 |

| macroeconomics | 126.9 |

| externality | 126.9 |

| inappropriable | 126.2 |

| nonmoney | 125.7 |

| epts | 125.4 |

| oversales | 122.0 |

| monopolistic | 121.5 |

| lossa | 121.3 |

| mpl | 121.2 |

| intercharge | 119.2 |

| mrsr | 118.5 |

| disinflation | 117.8 |

| hapte | 117.3 |

| berck | 117.3 |

| overproviding | 116.7 |

| repairperson | 114.4 |

| dissave | 109.7 |

| nonexportable | 109.5 |

| rebuying | 109.4 |

| underproduction | 108.3 |

| caff | 108.1 |

| isoelastic | 107.9 |

| tangencies | 106.2 |

| tangency | 105.2 |

| inelastic | 102.4 |

| nonlibrarian | 101.9 |

| homebodies | 100.5 |

| underproduced | 100.0 |

| elasticity | 99.1 |

| duopoly | 99.1 |

| overinformed | 98.9 |

| elasticities | 98.7 |

| nonpremium | 98.0 |

| paribus | 93.9 |

| unionizes | 93.0 |

| ceteris | 92.0 |

| prepriced | 91.5 |

| monopolists | 90.9 |

| noneconomists | 90.7 |

| switchgears | 90.6 |

| misallocated | 90.6 |

| monetarist | 90.6 |

| coalmaster | 90.1 |

| oligopolistic | 88.2 |

| quasilinear | 87.7 |

| oligopsonies | 87.4 |

| overinsure | 86.9 |

| cartelize | 86.3 |

| mpc | 85.7 |

| gerik | 84.9 |

| forgone | 84.3 |

| externalities | 84.2 |

| curve | 84.2 |

| mrp | 83.5 |

| noninflationary | 83.2 |

| stagflation | 83.0 |

| noneconomist | 82.6 |

| hoisters | 79.9 |

| depreciates | 79.7 |

| disinflations | 79.5 |

| takeaways | 79.5 |

| atc | 79.1 |

| demander | 78.7 |

| potterville | 77.5 |

| prot | 77.1 |

| recessions | 76.8 |

| diversifiable | 76.5 |

| multiplier | 76.4 |

| bushels | 73.5 |

| ungreat | 73.2 |

| underbids | 72.2 |

| dominiums | 72.1 |

| exhaustible | 71.8 |

| economists | 71.6 |

| dissavings | 71.6 |

| productivities | 71.4 |

| gien | 71.4 |

| netbooks | 71.3 |

| flyswatters | 71.3 |

| snowblowers | 71.1 |

| imperfectively | 70.9 |

| intis | 70.4 |

| telebanking | 69.8 |

| misallocations | 69.7 |

| quantity | 69.0 |

| seignorage | 68.5 |

| untillable | 68.4 |

| actuarily | 68.3 |

| kamika | 68.0 |

| superduper | 67.6 |

| gdp | 67.5 |

| nonprofitability | 67.4 |

| aggregate | 67.3 |

| underconsumed | 67.0 |

| windsurfs | 66.9 |

| antimerger | 66.8 |

| pizzas | 66.6 |

| overprovided | 66.2 |

| noncompeting | 66.0 |

| marketa | 65.6 |

| monopoly | 65.3 |

| inefficiently | 65.3 |

| mpp | 65.1 |

| deflator | 64.9 |

| monetarism | 64.7 |

| overproduces | 64.4 |

| nonexclusion | 64.1 |

| redeposits | 64.0 |

| tollbridge | 64.0 |

| dxt | 63.8 |

| tfc | 63.7 |

| undermeasured | 63.6 |

| logrolling | 63.3 |

| costlessly | 62.9 |

| surplus | 62.9 |

| nondiscount | 62.8 |

| disinflate | 62.6 |

| dcor | 62.0 |

| noncompulsive | 61.9 |

| rtsl | 61.7 |

| equilibrium | 60.8 |

| peasouper | 60.8 |

| oer | 60.3 |

| gristly | 58.9 |

| featherbedding | 58.5 |

| overplanting | 57.6 |

| nonreversibility | 57.5 |

| scalpers | 57.4 |

| prefreeze | 57.3 |

| inflation | 57.1 |

| microeconomic | 56.6 |

| keynesian | 56.3 |

| cornland | 56.3 |

| outfish | 55.6 |

| maximizes | 55.1 |

| autarky | 54.7 |

| precontrol | 54.6 |

| misallocates | 54.3 |

| collude | 54.2 |

| monopsonists | 53.9 |

| relends | 53.7 |

| retexturing | 53.6 |

| cartelizing | 53.1 |

| nautica | 53.0 |

| nonstandardization | 52.7 |

| nonsatisfaction | 52.6 |

| burritos | 52.6 |

| noncredible | 52.6 |

| superexpensive | 52.5 |

| shirking | 52.5 |

| stayover | 52.4 |

| bushel | 52.4 |

| minishing | 52.3 |

| noncooperative | 52.3 |

| marginalism | 52.1 |

| unrecoverably | 52.1 |

| decafs | 51.8 |

| nondiscriminating | 51.6 |

| earns | 51.1 |

| aggeration | 50.9 |

| xms | 50.6 |

| gonzlez | 50.6 |

| dowment | 50.5 |

| superfunction | 50.4 |

| demand | 50.2 |

| maximization | 50.1 |

| genos | 50.0 |

| grinches | 49.7 |

| calzones | 49.3 |

| bads | 49.1 |

| stairlike | 48.7 |

| duopolies | 48.1 |

| coconuts | 48.0 |

| precommit | 47.8 |

| hyperinflation | 47.8 |

| keynesians | 47.5 |

| averter | 47.3 |

| suers | 47.2 |

| price | 46.9 |

| remint | 46.6 |

| underpower | 46.6 |

| overinvest | 45.9 |

| overdifferentiation | 45.8 |

| costless | 45.7 |

| undertaxed | 45.6 |

| submarket | 45.5 |

| wahoo | 45.5 |

| misallocation | 45.3 |

| rms | 45.3 |

| collusive | 45.2 |

| repractice | 45.1 |

| kumquats | 45.0 |

| msb | 44.5 |

| cutto | 44.5 |

| inflationary | 44.2 |

| disinflationary | 44.1 |

| preannounce | 44.0 |

| korunas | 43.9 |

| peso | 43.7 |

| oligopsony | 43.6 |

| overcompensates | 43.5 |

| nonoptimal | 43.5 |

| djt | 43.4 |

| trillions | 43.1 |

| cappuccinos | 43.0 |

| dnx | 43.0 |

| cartelized | 43.0 |

| antipollution | 42.8 |

| deflation | 42.6 |

| sellers | 42.5 |

| thrifts | 42.4 |

| megadeal | 42.0 |

| unemployment | 41.9 |

| supersaver | 41.7 |

| antitheft | 41.5 |

| afc | 41.4 |

| excludability | 41.1 |

| cartel | 41.0 |

| inelasticity | 40.7 |

| indifference | 40.6 |

| carpetmaking | 40.4 |

| diminishing | 40.3 |

| postponable | 40.2 |

| backflows | 40.1 |

| preemergency | 39.9 |

| pesos | 39.9 |

| ricardian | 39.9 |

| nongraduates | 39.9 |

| excludable | 39.9 |

| chunnel | 39.8 |

| multiproduct | 39.7 |

| rebating | 39.7 |

| autoworker | 39.5 |

| postcontract | 39.4 |

| misestimated | 39.2 |

| mcpo | 39.1 |

| perfectively | 39.0 |

| payoffs | 38.9 |

| carlena | 38.9 |

| misestimate | 38.8 |

| haircutters | 38.7 |

| noncontrollable | 38.6 |

| overexpand | 38.3 |

| speat | 38.0 |

| cartelization | 37.9 |

| belion | 37.7 |

| redistributes | 37.7 |

| bailbond | 37.6 |

| rises | 37.6 |

| macroeconomic | 37.5 |

| overutilize | 37.4 |

| toyotas | 37.2 |

| overutilized | 37.0 |

| disposable | 37.0 |

| overvalued | 37.0 |

| hamburgers | 36.9 |

| bolivias | 36.8 |

| cpi | 36.5 |

| substitutes | 36.4 |

| curves | 36.2 |

| mpb | 36.1 |

| guilders | 36.1 |

| onethe | 36.1 |

| luters | 35.9 |

| subsidizes | 35.9 |

| dvc | 35.8 |

| reengineers | 35.7 |

| multiplant | 35.7 |

| overbook | 35.7 |

| vlor | 35.4 |

| poolers | 35.4 |

| macks | 35.4 |

| savers | 35.3 |

| preloan | 35.2 |

| pareto | 35.2 |

| righties | 35.2 |

| deadstock | 35.1 |

| firms | 35.1 |

| nonindexed | 35.0 |

| cokie | 34.9 |

| substitutability | 34.7 |

| kinked | 34.7 |

| summar | 34.6 |

| intersects | 34.5 |

| complier | 34.5 |

| rebegin | 34.5 |

| clich | 34.4 |

| proprietorships | 34.4 |

| rationing | 34.3 |

| monopolies | 34.3 |

| recession | 34.2 |

| lattes | 34.1 |

| depreciate | 34.0 |

| output | 33.6 |

| overconsumed | 33.5 |

| supply | 33.5 |

| wage | 33.4 |

| unforecasted | 33.3 |

| safekeeper | 33.3 |

| bundling | 33.0 |

| buyers | 33.0 |

| ringgits | 33.0 |

| inframarginal | 33.0 |

| disinvesting | 32.9 |

| quintile | 32.9 |

| basketballs | 32.7 |

| equals | 32.7 |

| billfolds | 32.6 |

| posttax | 32.6 |

| seigniorage | 32.5 |

| sml | 32.5 |

| qmc | 32.5 |

| pricefixing | 32.3 |

| inflations | 32.2 |

| antigrowth | 32.1 |

| underproducing | 31.9 |

| contraltos | 31.9 |

| countersue | 31.8 |

| starvers | 31.7 |

| overbidding | 31.6 |

| autoworkers | 31.4 |

| incomes | 31.2 |

| utility | 31.2 |

| decontrolling | 31.2 |

| frictional | 31.2 |

| mux | 31.1 |

| nominal | 31.0 |

| surpluses | 31.0 |

| uninsurable | 31.0 |

| ppc | 31.0 |

| snowboard | 30.8 |

| unexploited | 30.8 |

| overgraze | 30.8 |

| chevrolets | 30.8 |

| decontrolled | 30.6 |

| echikson | 30.6 |

| hyperrational | 30.4 |

| overutilizing | 30.4 |

| smoothies | 30.4 |

| yens | 30.3 |

| inefficiency | 30.2 |

| entres | 30.1 |

| diseconomy | 30.0 |

| randomizes | 29.9 |

| trustbusters | 29.9 |

| payoff | 29.9 |

| commercializes | 29.8 |

| bepress | 29.8 |

| nonlocals | 29.7 |

| buys | 29.7 |

| roundaboutness | 29.7 |

| nonneutrality | 29.6 |

| elysburg | 29.4 |

| contestable | 29.3 |

| supercompetitive | 29.2 |

| litterbugs | 29.1 |

| avocados | 29.0 |

| shiftability | 29.0 |

| damager | 28.9 |

| retime | 28.7 |

| overissuance | 28.7 |

| disutility | 28.5 |

| cleanings | 28.4 |

| propecia | 28.4 |

| hubbard | 28.4 |

| nonmarket | 28.3 |

| salsas | 28.1 |

| depletable | 28.1 |

| prices | 28.0 |

| maximized | 28.0 |

| haircuts | 28.0 |

| entrep | 28.0 |

| kiloliter | 27.9 |

| arbitrager | 27.8 |

| spendable | 27.7 |

| quintiles | 27.6 |

| edgeworth | 27.5 |

| substitution | 27.4 |

| outproduce | 27.3 |

| lobstermen | 27.3 |

| truckful | 27.2 |

| pengos | 27.2 |

| overprice | 27.1 |

| earfuls | 27.0 |

| complements | 27.0 |

| unrented | 26.9 |

| trilemma | 26.9 |

| prilosec | 26.9 |

| economizes | 26.9 |

| pepsi | 26.8 |

| substitutable | 26.6 |

| intramarginal | 26.6 |

| atter | 26.5 |

| colluding | 26.5 |

| nonstriking | 26.3 |

| birthrates | 26.2 |

| taxicabs | 26.2 |

| reselling | 26.2 |

Top 500 underused words

| Word | Frequency relative to Google corpus |

|---|---|

| anti | 0.0009 |

| jewish | 0.0010 |

| proteins | 0.0018 |

| god | 0.0018 |

| tumor | 0.0019 |

| neck | 0.0020 |

| damn | 0.0023 |

| gospel | 0.0024 |

| jesus | 0.0024 |

| islam | 0.0024 |

| paused | 0.0026 |

| bent | 0.0026 |

| renal | 0.0026 |

| ladies | 0.0027 |

| acids | 0.0028 |

| ritual | 0.0028 |

| servant | 0.0028 |

| poems | 0.0030 |

| moses | 0.0030 |

| wounded | 0.0030 |

| lips | 0.0031 |

| pursuant | 0.0032 |

| finger | 0.0033 |

| neural | 0.0033 |

| darkness | 0.0033 |

| hebrew | 0.0033 |

| chem | 0.0033 |

| ass | 0.0034 |

| enzyme | 0.0034 |

| soul | 0.0034 |

| atomic | 0.0035 |

| hello | 0.0036 |

| multi | 0.0037 |

| doi | 0.0038 |

| dare | 0.0038 |

| narrative | 0.0039 |

| sins | 0.0039 |

| activated | 0.0040 |

| stakeholders | 0.0040 |

| divine | 0.0040 |

| psychiatric | 0.0040 |

| sexuality | 0.0041 |

| physiological | 0.0042 |

| hormone | 0.0042 |

| warmth | 0.0042 |

| pathways | 0.0042 |

| prayer | 0.0043 |

| grin | 0.0043 |

| rape | 0.0043 |

| gods | 0.0044 |

| genre | 0.0044 |

| abdominal | 0.0044 |

| brave | 0.0044 |

| markers | 0.0046 |

| template | 0.0046 |

| cerebral | 0.0047 |

| pastor | 0.0047 |

| hypertension | 0.0047 |

| gay | 0.0047 |

| negro | 0.0048 |

| bishop | 0.0049 |

| archeological | 0.0049 |

| teaspoon | 0.0050 |

| clinical | 0.0050 |

| palace | 0.0050 |

| dysfunction | 0.0050 |

| echo | 0.0051 |

| supper | 0.0051 |

| elbow | 0.0052 |

| bibliography | 0.0052 |

| amplitude | 0.0052 |

| deployment | 0.0052 |

| organism | 0.0053 |

| gratitude | 0.0053 |

| hallway | 0.0054 |

| shining | 0.0054 |

| lord | 0.0054 |

| lit | 0.0054 |

| poets | 0.0054 |

| antibodies | 0.0055 |

| non | 0.0055 |

| murdered | 0.0055 |

| aloud | 0.0056 |

| ideals | 0.0056 |

| cheek | 0.0057 |

| eternal | 0.0057 |

| sofa | 0.0058 |

| thickness | 0.0059 |

| smiles | 0.0059 |

| waiver | 0.0059 |

| afterwards | 0.0060 |

| catholic | 0.0060 |

| tumors | 0.0061 |

| chest | 0.0062 |

| boiling | 0.0062 |

| mediation | 0.0062 |

| swear | 0.0062 |

| counselor | 0.0062 |

| grabbed | 0.0062 |

| gaze | 0.0063 |

| heavens | 0.0063 |

| salvation | 0.0063 |

| bleeding | 0.0063 |

| teachings | 0.0063 |

| naval | 0.0064 |

| manners | 0.0064 |

| christians | 0.0064 |

| yeah | 0.0064 |

| spirituality | 0.0065 |

| muscle | 0.0065 |

| stairs | 0.0065 |

| prose | 0.0065 |

| tissues | 0.0065 |

| kissing | 0.0066 |

| greeks | 0.0066 |

| whilst | 0.0066 |

| insertion | 0.0067 |

| hon | 0.0067 |

| serum | 0.0067 |

| sophie | 0.0067 |

| pillow | 0.0067 |

| commander | 0.0067 |

| delete | 0.0067 |

| forehead | 0.0068 |

| luke | 0.0068 |

| holy | 0.0068 |

| monk | 0.0068 |

| cheeks | 0.0069 |

| fairy | 0.0069 |

| glory | 0.0069 |

| goodbye | 0.0069 |

| scriptures | 0.0069 |

| gown | 0.0070 |

| gland | 0.0070 |

| sanctuary | 0.0070 |

| forgive | 0.0070 |

| detector | 0.0070 |

| prophet | 0.0070 |

| cave | 0.0071 |

| christianity | 0.0071 |

| amino | 0.0071 |

| winding | 0.0071 |

| breath | 0.0071 |

| textual | 0.0071 |

| mortal | 0.0071 |

| slept | 0.0072 |

| spine | 0.0072 |

| savior | 0.0073 |

| sensor | 0.0073 |

| sip | 0.0073 |

| biomass | 0.0073 |

| rebel | 0.0074 |

| bandwidth | 0.0074 |

| nausea | 0.0075 |

| appearances | 0.0075 |

| intellect | 0.0076 |

| biopsy | 0.0077 |

| herbs | 0.0077 |

| sensation | 0.0077 |

| superintendent | 0.0077 |

| font | 0.0077 |

| mentor | 0.0077 |

| acta | 0.0077 |

| sect | 0.0077 |

| mama | 0.0078 |

| dedication | 0.0078 |

| trauma | 0.0078 |

| muslim | 0.0078 |

| snapped | 0.0078 |

| patches | 0.0079 |

| lad | 0.0079 |

| lust | 0.0079 |

| appl | 0.0079 |

| semantics | 0.0079 |

| visualization | 0.0079 |

| marsh | 0.0080 |

| ribbon | 0.0080 |

| empowerment | 0.0080 |

| grammar | 0.0080 |

| soc | 0.0080 |

| int | 0.0080 |

| confidentiality | 0.0081 |

| fiction | 0.0081 |

| calibration | 0.0081 |

| asleep | 0.0081 |

| flung | 0.0081 |

| eur | 0.0082 |

| bible | 0.0082 |

| encoding | 0.0082 |

| antenna | 0.0082 |

| beloved | 0.0083 |

| twisted | 0.0083 |

| neurological | 0.0083 |

| upstairs | 0.0083 |

| smile | 0.0084 |

| madam | 0.0084 |

| dreaming | 0.0084 |

| sleeve | 0.0084 |

| intravenous | 0.0084 |

| heel | 0.0084 |

| knocked | 0.0085 |

| parted | 0.0085 |

| collaboration | 0.0085 |

| glowing | 0.0085 |

| verse | 0.0086 |

| memoirs | 0.0086 |

| polymer | 0.0086 |

| faint | 0.0086 |

| olivia | 0.0086 |

| submission | 0.0087 |

| der | 0.0087 |

| frowned | 0.0087 |

| annex | 0.0087 |

| habitats | 0.0087 |

| absorption | 0.0087 |

| disgust | 0.0088 |

| jaw | 0.0088 |

| preacher | 0.0088 |

| latino | 0.0088 |

| softly | 0.0088 |

| sensations | 0.0088 |

| pale | 0.0089 |

| apologize | 0.0089 |

| tense | 0.0089 |

| torture | 0.0089 |

| mourning | 0.0089 |

| deposition | 0.0089 |

| sexual | 0.0090 |

| impairment | 0.0091 |

| morrow | 0.0091 |

| beam | 0.0091 |

| pleading | 0.0091 |

| staring | 0.0092 |

| topical | 0.0092 |

| porch | 0.0092 |

| nerve | 0.0092 |

| sodium | 0.0092 |

| offenses | 0.0093 |

| kiss | 0.0093 |

| aye | 0.0093 |

| protocols | 0.0094 |

| cute | 0.0094 |

| eng | 0.0094 |

| horn | 0.0095 |

| farewell | 0.0095 |

| shone | 0.0095 |

| colonization | 0.0095 |

| pray | 0.0095 |

| inquiries | 0.0095 |

| glasgow | 0.0095 |

| remembers | 0.0095 |

| theatrical | 0.0095 |

| pity | 0.0095 |

| elder | 0.0096 |

| smiling | 0.0096 |

| activate | 0.0096 |

| screamed | 0.0097 |

| imperialism | 0.0097 |

| texture | 0.0097 |

| utmost | 0.0097 |

| irritation | 0.0097 |

| self | 0.0097 |

| battlefield | 0.0098 |

| jerusalem | 0.0099 |

| disbelief | 0.0099 |

| spiritual | 0.0100 |

| pulses | 0.0101 |

| humility | 0.0101 |

| colonel | 0.0101 |

| dna | 0.0101 |

| legitimacy | 0.0101 |

| policeman | 0.0101 |

| hum | 0.0102 |

| curtis | 0.0102 |

| believer | 0.0102 |

| tidal | 0.0102 |

| hesitated | 0.0103 |

| bristol | 0.0103 |

| viral | 0.0103 |

| aroused | 0.0103 |

| fungi | 0.0103 |

| laughing | 0.0103 |

| marching | 0.0104 |

| vessel | 0.0104 |

| feminist | 0.0104 |

| emergent | 0.0105 |

| thoracic | 0.0105 |

| pulse | 0.0106 |

| islamic | 0.0106 |

| rue | 0.0106 |

| sang | 0.0106 |

| signatures | 0.0106 |

| laughs | 0.0106 |

| implicated | 0.0106 |

| mask | 0.0106 |

| prophetic | 0.0106 |

| bodily | 0.0107 |

| epilepsy | 0.0107 |

| vols | 0.0107 |

| dances | 0.0108 |

| cowboy | 0.0108 |

| neuron | 0.0108 |

| ovarian | 0.0108 |

| endurance | 0.0108 |

| nos | 0.0108 |

| interpreter | 0.0108 |

| tel | 0.0109 |

| architecture | 0.0109 |

| unconscious | 0.0109 |

| consciousness | 0.0109 |

| synthesized | 0.0110 |

| rituals | 0.0110 |

| drowned | 0.0110 |

| glorious | 0.0111 |

| hereditary | 0.0111 |

| buddhist | 0.0111 |

| fraser | 0.0111 |

| cos | 0.0111 |

| sorrow | 0.0111 |

| modal | 0.0111 |

| shaft | 0.0111 |

| shrugged | 0.0111 |

| exile | 0.0111 |

| churches | 0.0112 |

| mythology | 0.0112 |

| clad | 0.0112 |

| porous | 0.0112 |

| intermittent | 0.0113 |

| tugged | 0.0113 |

| peeled | 0.0113 |

| inquired | 0.0113 |

| memorandum | 0.0113 |

| mouth | 0.0114 |

| comp | 0.0114 |

| teasing | 0.0114 |

| treasures | 0.0114 |

| downstairs | 0.0114 |

| della | 0.0114 |

| upright | 0.0114 |

| brook | 0.0114 |

| gonna | 0.0115 |

| commandments | 0.0115 |

| diagnosis | 0.0116 |

| homosexuality | 0.0116 |

| heroes | 0.0116 |

| jessie | 0.0116 |

| seminars | 0.0116 |

| exquisite | 0.0116 |

| brigade | 0.0117 |

| mortar | 0.0117 |

| startled | 0.0118 |

| hague | 0.0118 |

| kidding | 0.0118 |

| mutation | 0.0118 |

| sword | 0.0119 |

| youthful | 0.0119 |

| roared | 0.0120 |

| thyroid | 0.0120 |

| longed | 0.0120 |

| univ | 0.0120 |

| tongue | 0.0120 |

| travis | 0.0120 |

| cooler | 0.0120 |

| decoration | 0.0120 |

| legs | 0.0120 |

| shoulders | 0.0121 |

| muddy | 0.0121 |

| chin | 0.0121 |

| juvenile | 0.0121 |

| welcoming | 0.0121 |

| missionary | 0.0121 |

| singh | 0.0122 |

| cinnamon | 0.0122 |

| tone | 0.0122 |

| brow | 0.0122 |

| oath | 0.0122 |

| sequencing | 0.0122 |

| eyed | 0.0123 |

| accent | 0.0123 |

| bedside | 0.0123 |

| rifles | 0.0123 |

| sediment | 0.0123 |

| arterial | 0.0123 |

| relieved | 0.0124 |

| affirmation | 0.0124 |

| breasts | 0.0124 |

| indigenous | 0.0124 |

| charming | 0.0124 |

| coll | 0.0125 |

| tang | 0.0125 |

| surrendered | 0.0125 |

| canyon | 0.0125 |

| workflow | 0.0125 |

| leaped | 0.0125 |

| collaborative | 0.0125 |

| stationed | 0.0125 |

| charleston | 0.0125 |

| liaison | 0.0125 |

| grande | 0.0126 |

| prophets | 0.0126 |

| tick | 0.0126 |

| temperament | 0.0126 |

| girl | 0.0126 |

| pupils | 0.0126 |

| biochemistry | 0.0127 |

| beard | 0.0127 |

| counsel | 0.0127 |

| gill | 0.0127 |

| stat | 0.0127 |

| obstruction | 0.0128 |

| contempt | 0.0128 |

| amusing | 0.0128 |

| stout | 0.0128 |

| connor | 0.0129 |

| parkinson | 0.0129 |

| toes | 0.0129 |

| baptist | 0.0129 |

| companions | 0.0129 |

| angel | 0.0129 |

| muslims | 0.0130 |

| climax | 0.0130 |

| poem | 0.0130 |

| thou | 0.0130 |

| evelyn | 0.0130 |

| mater | 0.0131 |

| yelled | 0.0131 |

| neurology | 0.0131 |

| subdivision | 0.0131 |

| cicero | 0.0131 |

| skinny | 0.0131 |

| baltic | 0.0131 |

| intently | 0.0131 |

| romans | 0.0132 |

| cognitive | 0.0132 |

| reconstructed | 0.0132 |

| cranial | 0.0132 |

| knees | 0.0132 |

| paralysis | 0.0132 |

| dear | 0.0132 |

| dialog | 0.0132 |

| eyebrows | 0.0133 |

| skin | 0.0133 |

| trainer | 0.0133 |

| tcp | 0.0133 |

| psychiatry | 0.0134 |

| liberation | 0.0134 |

| gently | 0.0134 |

| expelled | 0.0134 |

| testament | 0.0134 |

| thee | 0.0134 |

| respectful | 0.0134 |

| rehabilitation | 0.0134 |

| categorical | 0.0135 |

| chased | 0.0135 |

| detention | 0.0135 |

| limp | 0.0135 |

| architectural | 0.0135 |

| symbolism | 0.0135 |

| backup | 0.0135 |

| savannah | 0.0136 |

| conquer | 0.0136 |

| recollection | 0.0136 |

| infiltration | 0.0136 |

| chronicles | 0.0136 |

| workload | 0.0137 |

| oppressive | 0.0137 |

| screw | 0.0137 |

| affinity | 0.0137 |

| che | 0.0137 |

| organisms | 0.0137 |

| censorship | 0.0137 |

| isaiah | 0.0137 |

| bless | 0.0138 |

| statutory | 0.0138 |

| learner | 0.0138 |

| celtic | 0.0138 |

| irene | 0.0138 |

| sounded | 0.0138 |

| legion | 0.0138 |

| incidents | 0.0138 |

| disciples | 0.0138 |

| termination | 0.0138 |

| jewel | 0.0138 |

| majesty | 0.0139 |

| orient | 0.0139 |

| tears | 0.0139 |

| posture | 0.0139 |

| church | 0.0139 |

| rusty | 0.0140 |

| handler | 0.0140 |

| molecular | 0.0140 |

| exhibitions | 0.0140 |

| monument | 0.0140 |

| alison | 0.0141 |

| genesis | 0.0141 |

| dialogs | 0.0141 |

| compassionate | 0.0141 |

| darcy | 0.0141 |

| dad | 0.0141 |

| delegation | 0.0141 |

Top 500 missing words

| Word | Percentile |

|---|---|

| christ | 0.998 |

| smiled | 0.997 |

| nodded | 0.997 |

| laughed | 0.996 |

| jews | 0.995 |

| stared | 0.995 |

| throat | 0.994 |

| glanced | 0.994 |

| whispered | 0.994 |

| leaned | 0.993 |

| membrane | 0.993 |

| electron | 0.993 |

| worship | 0.992 |

| theology | 0.992 |

| lateral | 0.992 |

| receptor | 0.992 |

| kissed | 0.992 |

| activation | 0.992 |

| sighed | 0.991 |

| pulmonary | 0.991 |

| shit | 0.991 |

| para | 0.991 |

| shaking | 0.991 |

| laughter | 0.991 |

| lieutenant | 0.990 |

| lesions | 0.990 |

| verb | 0.990 |

| anterior | 0.990 |

| ieee | 0.990 |

| glucose | 0.989 |

| theological | 0.989 |

| retrieved | 0.989 |

| folder | 0.989 |

| scripture | 0.989 |

| cfr | 0.989 |

| sensory | 0.989 |

| proc | 0.989 |

| mediated | 0.989 |

| vascular | 0.989 |

| supra | 0.989 |

| alien | 0.989 |

| fuck | 0.989 |

| receptors | 0.989 |

| spinal | 0.988 |

| geog | 0.988 |

| waist | 0.988 |

| priests | 0.988 |

| learners | 0.988 |

| pathway | 0.988 |

| covenant | 0.988 |

| grinned | 0.988 |

| clin | 0.988 |

| fragments | 0.988 |

| subpart | 0.988 |

| rhythm | 0.988 |

| que | 0.988 |

| phys | 0.988 |

| metabolism | 0.988 |

| fracture | 0.988 |

| fatigue | 0.988 |

| cir | 0.988 |

| substrate | 0.988 |

| waved | 0.988 |

| inflammatory | 0.987 |

| narratives | 0.987 |

| fucking | 0.987 |

| ref | 0.987 |

| prayers | 0.987 |

| binary | 0.987 |

| adolescents | 0.987 |

| metabolic | 0.987 |

| urine | 0.987 |

| flame | 0.987 |

| chapel | 0.987 |

| belly | 0.987 |

| nucleus | 0.987 |

| shear | 0.987 |

| noun | 0.987 |

| specimens | 0.987 |

| custody | 0.987 |

| corpus | 0.986 |

| wounds | 0.986 |

| freud | 0.986 |

| biol | 0.986 |

| rna | 0.986 |

| gradient | 0.986 |

| hurried | 0.986 |

| stare | 0.986 |

| muttered | 0.986 |

| specimen | 0.986 |

| swallowed | 0.986 |

| enzymes | 0.986 |

| kant | 0.986 |

| hips | 0.986 |

| seq | 0.986 |

| meditation | 0.986 |

| silently | 0.986 |

| anglo | 0.986 |

| butler | 0.986 |

| anthropology | 0.986 |

| fetal | 0.986 |

| parliamentary | 0.986 |

| murmured | 0.986 |

| regiment | 0.986 |

| infantry | 0.986 |

| tribunal | 0.986 |

| inhibition | 0.986 |

| toxicity | 0.986 |

| saints | 0.986 |

| arabic | 0.986 |

| inflammation | 0.986 |

| skull | 0.986 |

| oxidation | 0.985 |

| scattering | 0.985 |

| rubbed | 0.985 |

| racism | 0.985 |

| maggie | 0.985 |

| meta | 0.985 |

| notification | 0.985 |

| satan | 0.985 |

| carcinoma | 0.985 |

| enlightenment | 0.985 |

| chambers | 0.985 |

| altar | 0.985 |

| lily | 0.985 |

| vitro | 0.985 |

| ventricular | 0.985 |

| vapor | 0.985 |

| parish | 0.985 |

| genome | 0.985 |

| spectral | 0.985 |

| feminine | 0.985 |

| spectra | 0.985 |

| prayed | 0.985 |

| modernity | 0.985 |

| sql | 0.985 |

| trustee | 0.985 |

| relational | 0.985 |

| cemetery | 0.985 |

| pathology | 0.985 |

| verses | 0.985 |

| mistress | 0.984 |

| verbs | 0.984 |

| artifacts | 0.984 |

| lodge | 0.984 |

| reactive | 0.984 |

| motions | 0.984 |

| cock | 0.984 |

| antibody | 0.984 |

| resurrection | 0.984 |

| luther | 0.984 |

| congregation | 0.984 |

| hindu | 0.984 |

| mol | 0.984 |

| distal | 0.984 |

| instructional | 0.984 |

| cathedral | 0.984 |

| nod | 0.984 |

| bladder | 0.984 |

| neo | 0.984 |

| lesion | 0.984 |

| goddess | 0.984 |

| cervical | 0.984 |

| reg | 0.983 |

| burial | 0.983 |

| inhibitors | 0.983 |

| ventilation | 0.983 |

| praying | 0.983 |

| morphology | 0.983 |

| obedience | 0.983 |

| syntax | 0.983 |

| discourses | 0.983 |

| cavalry | 0.983 |

| membranes | 0.983 |

| vivo | 0.983 |

| physiology | 0.983 |

| tablespoons | 0.983 |

| palestine | 0.983 |

| wavelength | 0.983 |

| temper | 0.983 |

| disciplinary | 0.983 |

| petitioner | 0.983 |

| archeology | 0.983 |

| psalm | 0.983 |

| tomb | 0.983 |

| battalion | 0.983 |

| trembling | 0.983 |

| tucked | 0.983 |

| urinary | 0.983 |

| chemotherapy | 0.983 |

| surg | 0.983 |

| deformation | 0.983 |

| nationalist | 0.983 |

| lattice | 0.983 |

| stirring | 0.983 |

| chromosome | 0.983 |

| sadness | 0.983 |

| hormones | 0.983 |

| potassium | 0.983 |

| augustine | 0.983 |

| fractures | 0.983 |

| invasive | 0.983 |

| anesthesia | 0.983 |

| gazed | 0.983 |

| ottoman | 0.983 |

| aboriginal | 0.983 |

| hug | 0.982 |

| bitch | 0.982 |

| narrator | 0.982 |

| medial | 0.982 |

| stained | 0.982 |

| flashed | 0.982 |

| malignant | 0.982 |

| jew | 0.982 |

| gasped | 0.982 |

| vibration | 0.982 |

| righteousness | 0.982 |

| chloride | 0.982 |

| intimacy | 0.982 |

| coating | 0.982 |

| buddha | 0.982 |

| antigen | 0.982 |

| angular | 0.982 |

| masculine | 0.982 |

| venous | 0.982 |

| righteous | 0.982 |

| demon | 0.982 |

| ashamed | 0.982 |

| lipid | 0.982 |

| airway | 0.982 |

| coarse | 0.982 |

| breathed | 0.982 |

| electrode | 0.982 |

| allah | 0.982 |

| huh | 0.982 |

| proximal | 0.982 |

| bowel | 0.982 |

| laden | 0.982 |

| judaism | 0.982 |

| fury | 0.982 |

| forensic | 0.982 |

| ankle | 0.982 |

| basal | 0.982 |

| soluble | 0.982 |

| palms | 0.982 |

| reinforcement | 0.982 |

| temples | 0.982 |

| blinked | 0.982 |

| hepatic | 0.982 |

| verlag | 0.982 |

| utter | 0.982 |

| innocence | 0.981 |

| seizures | 0.981 |

| congenital | 0.981 |

| schizophrenia | 0.981 |

| axial | 0.981 |

| demons | 0.981 |

| chuckled | 0.981 |

| precipitation | 0.981 |

| courtyard | 0.981 |

| dementia | 0.981 |

| appellate | 0.981 |

| bastard | 0.981 |

| thighs | 0.981 |

| lesbian | 0.981 |

| admiration | 0.981 |

| nasal | 0.981 |

| autism | 0.981 |

| buddhism | 0.981 |

| graves | 0.981 |

| shoved | 0.981 |

| intra | 0.981 |

| transverse | 0.981 |

| jealous | 0.981 |

| ontology | 0.981 |

| genus | 0.981 |

| slender | 0.981 |

| parenting | 0.981 |

| sermon | 0.981 |

| longing | 0.981 |

| affective | 0.981 |

| myocardial | 0.981 |

| auditory | 0.981 |

| coated | 0.981 |

| catheter | 0.981 |

| assay | 0.981 |

| spheres | 0.981 |

| authentication | 0.980 |

| vomiting | 0.980 |

| thigh | 0.980 |

| dorsal | 0.980 |

| subparagraph | 0.980 |

| commenced | 0.980 |

| skeletal | 0.980 |

| mammals | 0.980 |

| anemia | 0.980 |

| peptide | 0.980 |

| robe | 0.980 |

| baptism | 0.980 |

| holocaust | 0.980 |

| logan | 0.980 |

| danced | 0.980 |

| haired | 0.980 |

| hemorrhage | 0.980 |

| kinase | 0.980 |

| refugee | 0.980 |

| empathy | 0.980 |

| gastric | 0.980 |

| aortic | 0.980 |

| bishops | 0.980 |

| cohort | 0.980 |

| peered | 0.980 |

| adolescence | 0.980 |

| acknowledgments | 0.980 |

| supernatural | 0.980 |

| inhibitor | 0.980 |

| sperm | 0.980 |

| aquatic | 0.980 |

| judah | 0.980 |

| hegel | 0.980 |

| clinically | 0.980 |

| melbourne | 0.980 |

| bolt | 0.980 |

| socrates | 0.979 |

| fortress | 0.979 |

| squadron | 0.979 |

| cannon | 0.979 |

| modulation | 0.979 |

| situ | 0.979 |

| abu | 0.979 |

| lymph | 0.979 |

| aqueous | 0.979 |

| cortical | 0.979 |

| knot | 0.979 |

| appellant | 0.979 |

| foucault | 0.979 |

| communion | 0.979 |

| heidelberg | 0.979 |

| nietzsche | 0.979 |

| abdomen | 0.979 |

| reformation | 0.979 |

| landscapes | 0.979 |

| awe | 0.979 |

| tactical | 0.979 |

| summoned | 0.979 |

| commanders | 0.979 |

| arabs | 0.979 |

| intercourse | 0.979 |