Leaving California

August 12, 2025

Originally published at notes on cinema

James McMahon

To most of us, the beating heart of Hollywood film and TV is where we imagine it is supposed to be, in the historical studio lots of Hollywood, California. This must be where movie magic is made. To those working in film and TV production today, there is certainly not one dream factory, and even if there was, it would not be in Hollywood, in Greater Los Angeles, or even in California. Nowadays, it is likely that a Hollywood film or TV show is shot in other states, or in the cities of other countries, such as Vancouver and Toronto.

A recent blog post on FRED asked, “Is California losing its dominance in the film industry?” The post used employment data to show how motion picture and sound recording industry in California is declining as a share of national employment in the same industry. Figure 1 uses the same data as the blog post to visualize the components of this declining trend. Panel A shows the two components used to analyze California’s declining share. We notice right away that the employment being measured is not just motion picture employment, but employment in the sound recording industries as well. Ideally, an analysis of film industry employment would use data that is not aggregated with other industries. However, the obstacle is the availability of time series data where, at a lower level of the North American Industry Classification System, motion pictures and sound recording are split into subsector industry groups:

- Motion Picture and Video Industries (NAICS 5121)

- Sound Recording Industries (NAICS 5122)

Fortunately, Figure 2 shows how the employment of Motion Picture and Video Industries accounts for over 90% of the employment in Motion Picture and Sound Recording Industries (NAICS 512). This means that there is a high likelihood that a change in the employment of the motion picture and sound recording industries is an effect of an employment change in the film and television industries.

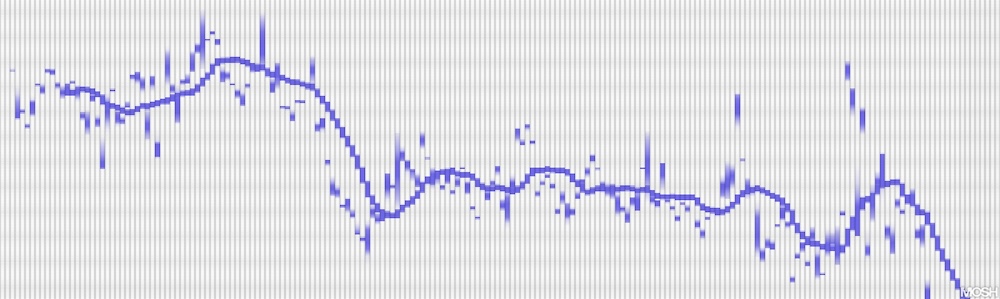

Panel B of Figure 1 shows 24-month percent changes to motion picture and sound recording employment in California and the United States. Panel C is our version of figure in the FRED blog post. Panel C demonstrates how the Californian share of motion picture and sound recording employment in the United States has been declining since the 1990s.

Source: FRED for All Employees, Motion Picture and Sound Recording Industries (CES5051200001) and All Employees: Information: Motion Picture and Sound Recording Industries in California (SMU06000005051200001SA).

Source: FRED for All Employees, Motion Picture and Video Industries (IPUJN5121W200000000) and All Employees: Information: Motion Picture and Sound Recording Industries (IPUJN512W200000000).

What can explain California’s decline from around 45% of all motion picture and sound recording employment to around 30%? To many people working in show business, there is a simple explanation: it is too expensive to shoot film and television in California (and, to some extent, New York). Why else would film and television production be migrating elsewhere?

This post will not disagree with clear evidence that several key occupations in film and television production are typically more expensive in California than in other states. For example, Figure 3 plots hourly wages for the occupation category Camera Operators, Television, Video, and Film (SOC code: 27-4031). In addition to national wage data, the figure plots the hourly wage at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentiles for the Los Angeles area, the state of California, and several states for comparison. The figure shows how camera operators are likely to be cheaper in places outside of Los Angeles and even the whole state of California.

Source: Bureau of Labour Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, May 2024

But beyond wage and salary differentials, California is something else: its labour is more unionized than other states. Many film and television projects cannot circumvent union labour, even if shooting is done outside of the United States. Yet, leaving California might be a way Hollywood’s major studios to force greater obedience out of its workforce — especially those who dream of their unions having more power in Hollywood.

Figure 4 shows a positive correlation (+0.47) between the rate of union membership in the motion picture industry and a 24-month moving average of California’s share of national employment in motion picture and sound industries (see Figure 1.C).

Source: Union membership data comes from Hirsch, Barry T., David A. Macpherson, and William E. Even (2025). Union Membership, Coverage, and Earnings from the CPS, found on unionstats,com.

This correlation is not strong enough to suggest that union rates of membership almost always go down when film and television production leaves California (more on this in a future post). However, the correlation is strong enough to make three guesses about the significance of the relationship:

- There might be more opportunities to hire non-union crews outside of California. Non-union crews can be “flipped” to a union crew in certain circumstances, but a non-union production might be attractive in places where labour can take less risks turning down freelance work.

- Freelancers are most in need of a union, but the low pay of freelance work might be, ironically, the financial barrier to affording union dues. An actor can become eligible for the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) after three days as a background actor or one day in a speaking role. However, not every person who is eligible for SAG would be in a position to afford the union initiation fee, annual dues, and work dues.

- Somehow the SAG union membership does not grow when film and television producers use the Taft–Hartley Act to hire non-union actors instead of union actors. Every time a non-union actor is used in a speaking or background role that should go to a SAG actor, the producer must produce a Taft-Hartley Report to justify why the non-union actor was used. The rule is that the SAG must be joined if the same non-union actor is “Taft-Hartleyed” three times. Maybe this threshold is being reached less frequently.

It seems unlikely that Hollywood major studios could forget about California labour entirely. Los Angeles is still America’s largest source of actors, screenwriters, makeup artists, set designers, stunt performers, and other jobs for film and television production. However, it is also possible that the Hollywood film business wants to use California’s film industry, with all of its skill and technical knowledge, but without showing desperation. The pendulum of power swings to the side of film and television unions if major studios are unable act on its threats to leave California or slow down film and television production.

Unfortunately, it does appear that Hollywood’s major studios can act on threats of leave California. In Figure 1C we see two “waterfalls”, which are the sharper drops in California’s share of motion picture and sound recording employment. The first waterfall is around the year 2000, and the second began in 2023 and appears to have continued to the most recent observation in 2025. The orange series in Figure 5 uses the Bureau of Labour Statistics detailed monthly listing of work stoppages in the United States since 1993. Workforce days idle is the product of the number of workers striking, multiplied by the number of days on strike. For example, a small workforce of 100 workers going on strike for 100 days is the same magnitude of 10,000 workers going on strike for 1 day. We are plotting the square root of the workforce days idle to help visualize smaller strikes.

The three largest strikes in the dataset that list California as a site are:

| States | Union | Union acronym | Work stoppage beginning date | Work stoppage ending date | Number of workers |

| AR, MA, IL, OH, TX, CO, NV, NM, UT, MI, FL, GA, HI, MN, MO, TN, NC, PA, OR, CA, WA, DC, MD | American Federation of Television and Radio Artists and Screen Actors Guild | AFTRA, SAG | 2000-05-01 | 2000-10-30 | 135000 |

| CA | United Food and Commercial Workers | UFCW | 2003-10-12 | 2004-02-29 | 67300 |

| CA, NY | Screen Actors Guild – American Federation of Television and Radio Artists | SAG-AFTRA | 2023-07-14 | 2023-11-08 | 160000 |

Two of California’s largest strikes since 1993 involved SAG-AFTRA and also occur close to or during these waterfall events in Figure 5.

Source: Bureau of Labour Statistics for Work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers, 1993-Present.