Home › Forum › Political Economy › Is Exchange Value Really Just Capitalized Use Value?

- This topic has 26 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated November 10, 2022 at 7:48 pm by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

CreatorTopic

-

October 6, 2022 at 10:44 pm #248394

If capitalism has only one pricing mechanism, then is exchange value actually distinct from use value?

According to CasP theory, capitalization is the process of discounting expected future value (in the case of capital assets, profits) to present value (e.g., share price or bond price) adjusted for risk. If capitalization is the only pricing mechanism in capitalism, this would imply that what Marx calls exchange value is, in fact, just discounted use value, i.e., exchange value is capitalized use value.

Of course, wages and wage labor predate the emergence of capitalism by thousands of years, which implies that capitalization predates capitalism by thousands of years.

If exchange value is just capitalized use value:

- Is there such a thing as a “surplus” (because wages represent the net present value of the future value of their services, adjusted for risk)?

- If there is no such thing as a surplus but there is nevertheless exploitation of labor, what is the source, cause, nexus, or locus of that exploitation?

- Without money, is there a basis for valuing anything, i.e., is the only viable value theory (and I use “viable” loosely) the “money theory of value”?

- Finally, what are the implications for CasP theory?

NOTE: I have recently argued that capitalism has two pricing mechanisms, one for commodities and one for capital assets. This argument should not be controversial in view of the Jesus Suaste Cherizola’s 2021 CasP Prize winning essay, which explores differences between commodities and capital assets through a CasP lens. While I think modeling capitalism as having two pricing mechanism is legitimate, I think accepting that there is only one pricing mechanism may be lead to a better understanding of capital and capitalism.

Thoughts? Thanks.

- This topic was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Scot Griffin.

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

October 7, 2022 at 5:41 pm #248398

If capitalization is the only pricing mechanism in capitalism, this would imply that what Marx calls exchange value is, in fact, just discounted use value, i.e., exchange value is capitalized use value.

Why do you say that discounting capitalizes use value (rather than power)?

Of course, wages and wage labor predate the emergence of capitalism by thousands of years, which implies that capitalization predates capitalism by thousands of years.

Capitalization was first used, embryonically, sometimes in the 14th century; was first formalized, if only tentatively, in the middle of the 19th century; and came into common use and full dominance in the second half of the 20th century. You can argue that capitalists were always forward-looking, and that the prices of their assets represented, or at least reflected, however unknowingly, future expectations. But I find it hard to think of the daily wage in Sumer as capitalizing something.

-

October 7, 2022 at 7:38 pm #248399

If capitalization is the only pricing mechanism in capitalism, this would imply that what Marx calls exchange value is, in fact, just discounted use value, i.e., exchange value is capitalized use value.

Why do you say that discounting capitalizes use value (rather than power)?

Capitalization is the discounting to present value of risk-adjusted expected future income. Here, by “use value” I mean an employer’s expected future income arising from the work contributed by an employee, and by “exchange value” I mean the wages paid by the employer to the employee for that expected future income. If that is a reasonable way to look at things, any difference between the employer’s future income and the employee’s wages arises from the act of discounting the employer’s expected future income to present value; i.e., wages can be considered the capitalization of the employee’s contribution to the employer’s expected future income.

Is that reasonable, or am I missing something?

Of course, wages and wage labor predate the emergence of capitalism by thousands of years, which implies that capitalization predates capitalism by thousands of years.

Capitalization was first used, embryonically, sometimes in the 14th century; was first formalized, if only tentatively, in the middle of the 19th century; and came into common use and full dominance in the second half of the 20th century. You can argue that capitalists were always forward-looking, and that the prices of their assets represented, or at least reflected, however unknowingly, future expectations. But I find it hard to think of the daily wage in Sumer as capitalizing something.

If an employee’s wages can properly be viewed as expressing the discounted present value of an employer’s risk-adjusted future income arising from the employee’s contribution, then the daily wage in Sumer can be said to have capitalized the employer’s expected future income.

Arguably, Marx’s surplus does not exist, if employees’ wages represent the employers’ discounted future income arising from the employee’s contribution. This is because wages, at least theoretically, represent the fair value of that contribution according to the logic of capitalization.

This does not mean that capital does not symbolize power (energy, actually, as capital and energy are stocks, while power is a flow), nor does it mean that workers are not exploited, but I think it does imply there is a source of social power anterior to capital, i.e., something caused non-capitalists to accept the logic of capitalism and its pricing mechanism of capitalization.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: Added final two paragraphs

-

October 8, 2022 at 9:10 pm #248404

1. I don’t understand the idea that capital discounts use value. The processes of power may or may not involve the creation of use value, but, in my view, capitalization is entirely independent of it.

2. In Sumer, wealth wasn’t thought of as Capital in the modern sense, let alone as discounted future earnings. Wealth was obtained by force, confiscation and royal/religious decree. There was no notion of “normal earnings” and “risk”. The future was deemed unknowable, subject to the whims of the gods. I don’t see the point of generalizing the modern ritual of orderly capitalization to pre-capitalist societies, let alone ancient ones.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

October 9, 2022 at 10:34 pm #248408

Scot Griffin,

I would counsel throwing classical economics’ value theory and Marx’s value theory out the window. Just throw it all out the window and start thinking from scratch again. This equates to throwing Utils and SNALTs out the window. I simply refer people to Bichler and Nitzan’s theory on this, plus relevant papers by Blair Fix, Ulf Martin and Jesus Suaste Cherizola. One really has to go back and read them again if one still feels baffled. (And I do still feel baffled at times so I do refer back.) The numeraire is not an objective measure of any real value. Market prices are not real measures of value. It’s better to say prices are instantiated by capital as power and thus demonstrate the power to price and not anything beyond that. Honestly, mentally jettisoning classical economics baggage is akin to throwing out the theory of the four humors so that one can understand physiology and disease in the modern scientific way via the study of biochemistry, cellular biology, physiology, pathogens and genetics. In other words, one has to throw out a false ontology (false theory of basic existents relevant to the discipline) for a correct (in the homomorphic modelling sense) ontology of the basic relevant existents.

There is some (maybe a lot, I don’t know) of modern orthodox economics which does theory which does not measure things in the numeraire or in Utils or SNALTS. I refer here to the Rank-Dependent Model of Generalized Expected Utility Value. I have nothing but a thumb-nail sketch understanding of this theory so I can say very little about it. Suffice it to say here, this theory is about measuring “expected value” on an ordinal scale not on a cardinal scale. A cardinal measurement scale is a measurement scale whose levels of measurement are numeric, like all the prices in a market. An ordinal scale merely ranks preferences, via “expected utility value”. When expected utility value is actually expressed by a purchase, trade or acquisition it is called “a revealed preference”.

All I will say here is that there are parts of orthodox economics where such economists could sensibly correspond and conceivably share or debate ideas with CasP theorists. This is just as modern Marxists (notably the Monthly Review style Marxists who are the most sensible of the modern Marxists in my view) could “do comparative economics” with and share ideas with the CasP theoreticians. But in each case they (orthodox and Marxist) won’t do this. Why not? Honestly, I would nominate certain dogmas (each of those schools has dogmas they simply will not give up), a know-it-all attitude (their school knows everything fundamental already and cannot possibly learn anything new from anyone outside their own academy) and careerism. Careerism, getting published in respected journals etcetera, dominates their thinking. A lot of minds out there are closed or semi-closed, living in their own hermetically sealed intellectual kingdoms. It’s all about power; capital as power, money as power, prestige as power, comeliness as power etc. etc. It’s all about power. Those who care about truth and seek it for its own sake and for the common good are passing rare. And not pure either: nobody’s perfect. 🙂

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Rowan Pryor.

-

October 10, 2022 at 10:17 pm #248416

1. I don’t understand the idea that capital discounts use value. The processes of power may or may not involve the creation of use value, but, in my view, capitalization is entirely independent of it.

To a certain extent, I am arguing that there is no such thing as exchange value, use value, or surplus. If we consider wages to be priced the same way capital assets are priced, i.e., wages represent the capitalization of value added by labor, then there is only one value, and that is equal to wages paid.

2. In Sumer, wealth wasn’t thought of as Capital in the modern sense, let alone as discounted future earnings. Wealth was obtained by force, confiscation and royal/religious decree. There was no notion of “normal earnings” and “risk”. The future was deemed unknowable, subject to the whims of the gods. I don’t see the point of generalizing the modern ritual of orderly capitalization to pre-capitalist societies, let alone ancient ones.

Sumerians understood the concepts of both compounding interest and discounting (e.g., via tax farm contracts), which are the inverse of one another. The fact that we have no evidence that Sumerians were as sophisticated about risk-adjusted discounting as the moderns does not mean they did not understand the basic outlines of it well enough for us to consider Sumerian wages as the “capitalization” of labor just as wages are today (if you accept that frame).

Again, I’ve argued in other comments in the forum that wages are priced like commodities and not capital assets, that capitalism, in fact, has two very different approaches to pricing things, but there is a good argument that “capitalization” is the pricing mechanism for everything in capitalism, that the perceived “mark-up” of commodities is just the accumulation of the risk-adjusted discounting of future value that the capitalist captures as profits through exchange of the end product, which eliminates the risk. What we call profits are just unwinding the discounting of the input costs to the seller’s benefit. Capitalists compress the future into the prices they pay for inputs, and they decompress that future when it becomes the present at the time of sale. Monetary exchanges are a time machine.

While capital could not exist without modern money, which allows wealth to accumulate as capital without affecting the circulation of money, there is a lot of evidence that most, if not all, of the basic concepts of capitalism, including risk-adjusted discounting and limited liability corporations, have been known for thousands of years. The conflict between hoarding and circulating hard money just prevented capitalism from coming into existence. Rome and Athens were too smart to allow private bankers to compete with the state money/credit system and ensured finance was part of the “state of hard money.” The only reason we have capitalism is because the Catholic church created a situation in which private finance created its own international money/credit system that came to dominate the intentionally anemic monetary (only) systems of individual sovereigns.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Scot Griffin.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: corrected a typo

-

October 10, 2022 at 10:42 pm #248417

Scot Griffin, I would counsel throwing classical economics’ value theory and Marx’s value theory out the window. Just throw it all out the window and start thinking from scratch again. This equates to throwing Utils and SNALTs out the window.

Thanks, Rowan.

Actually, I think what I’ve done here is to throw everything out the window, including CasP’s asserted history of modes of power (including the history of capitalism itself). Again, if there is only one pricing mechanism in capitalism, i.e., prices as the risk adjusted discounting of future value to present value, then there is no such thing as exchange value, use value, or surplus, and one needs to look elsewhere to site exploitation of the ruled (I look to money itself, regardless of how instituted).

I presented my thoughts as questions not because I was baffled or confused, but because I was trying to provoke responses that go beyond rejecting the very idea that the basic concepts that animate capitalism have been with us for thousands of years, at least since ancient Athens and Rome, if not earlier (e.g., Sumer). What makes capitalism “capitalism” is modern money, i.e., credit money, and the reason why modern money came about is the Catholic church prevented the integration of finance with the monetary system of “feudal” Europe, something that had been a hallmark of both Athens and Rome (aka “the state of hard money”). Finance was always part of the state of money-based societies until the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the Catholic church’s effort to establish itself as its own sovereign power by preventing the formation of state financial institutions. Private bankers had their own ideas.

Feudalism was an aberration, not an evolution of prior modes of power, and CasP’s story of prior modes of power is heavily burdened by Marx and those who came before him urging a new theodicy to explain extreme inequality in view of a new mode of power that claimed to stand for equality. While the private credit/money system of Europe did first come into existence around the 14th century, capitalism could not and did not exist until that kind of financial system merged with the “state” England with the founding of the Bank of England in 1692, creating what we understand today as modern money. The fact that some of what happened in the preceding 200-300 years looks a lot like capitalism only emphasizes that many of the concepts of capitalism predate it by a long while.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: edited for readability

-

October 11, 2022 at 5:10 pm #248425

Scot,

I must learn to restrict future imputations of confusion solely to myself. I manage to be confused by six of my previous day’s declarative statements before breakfast. That’s my mea culpa. I still struggle with the multiple extant ways of looking at economics. Also, my knowledge of history is only barely passable from about 1700 on. It’s weak to non-existent from times before that, especially my economic history. I’d better let the CasP theorists speak for themselves in this arena.

In attempting to unravel what I think of economics and political economy, I am still stuck at a much more fundamental level: at the level of what I call “empirical ontology” or the “ontology of real systems and formal systems”. It seems to me we have to clearly delineate between real systems where Fundamental Laws of nature operate and human ideational systems where Rules operate, specifically where axiomatic rules and algorithms operate in what we can term coded and programmed fashions which then recruit humans to obedient and coordinated actions. The litanies, rules, observances and performative operations which CasP theorists talk about, come under this heading of coded and programmed operations (encoded and executed by humans).

I came across a very interesting passage recently in a paper on virology. (I am not a virologist but I read papers in it from time to time.) It referred to self-assembly and coded assembly. The natural world exhibits features of both self-assembly and coded assembly at the level of life. Let us assume here that life begins at viruses. At the non-life and/or inorganic level, the natural world exhibits only self-assembly (where it is not exhibiting the plain old general cosmic process to ever greater entropy). A good example of self-assembly is the formation of a crystal under natural conditions. The paper I refer to states:

“In the same way that a roll of magnets will spontaneously assemble together, capsid proteins also exhibit self-assembly. The first to show this were H. Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams in 1955. They separated the RNA genome from the protein subunits of tobacco mosaic virus, and when they put them back together in a test tube, infectious virions formed automatically. This indicated that no additional information is necessary to assemble a virus: the physical components will assemble spontaneously, primarily held together by electrostatic and hydrophobic forces.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7150055/

People on this forum may well assume at this point I am down an esoteric rabbit hole unrelated to political economy. I don’t entirely think so but it’s a long discussion and I’ve never succeeded in making my case. Suffice it to say, the task in political economy is in my view to stop looking for natural laws in political economy (aside from the natural laws involving the exothermic, endothermic and self-assembly reactions which we utilise in the real economy for inorganic production and the biological laws of (RNA and DNA) coded assembly we utilise in organic production like food and fibre production). At all levels above this, political economy is about complex human behaviours and encoded laws (i.e. legal laws, regulations, conventions, rituals etc.). This is my view which is obviously partially derived from CasP insights.

Blair Fix, as illustrated in his article “Essentialism and Traditionalism in Academic Research”, is close to the mode of what I am endeavouring to look at or perhaps it’s better to say I am moving toward and influenced by the mode of scientific and philosophical analysis he demonstrates in such articles.

Getting back to talk about “value”, I think we have to be careful not to make the “mistake of metonymy”. The word “value” is vague and we use it at multiple levels with multiple meanings. Nietzsche came up with a very pithy aphorism implying the error of philosophising and reasoning with metonymies. I am still trying to find the quote again. In talking about “value” with various adjectives appended to it like “use value”, “exchange value”, “surplus value” etc. I think many can immediately make the mistake of considering these various values to be theoretically equatable and aggregateable in a common measure of value, the numeraire. I take this critique from CasP. We do performatively and algorithmically equate these values in quantities of the numeraire but this is a sort of transubstantiation trick. And again, Blair Fix has referred to the transubstantiation trick of finance ritual and market ritual where we all agree, or are forced to agree at the sword of penury and of social and career excommunication, that the transubstantiation is real.

As a footnote, people can refer to the book “On Kings” by David Graeber and Marshall Sahlins for the most florid example I think I have ever seen of doing philosophy by metonyomy. It’s ostensibly an anthropological text but I happen to think its elaborations and conclusions are pure philosophy by metonyomy. As an aside, I would be interested if anyone in the CasP group has read this monograph or any sections of it. I’d be interested in their opinions on it.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Rowan Pryor.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Rowan Pryor.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Rowan Pryor. Reason: Fixed typos

-

October 11, 2022 at 7:26 pm #248429

One of my graduate students in ‘Seven Lectures on Capital’, a course I taught at the Economics Department in Tel Aviv University many years ago, told me that “paleolithic individuals” (his term), just like present-day utility hunters at the shopping mall, made choices by subjecting their indifference maps to budget constraints. I kid you not.

Or, a recent simulation of the evolutionary origin of hierarchy argues that biological networks, from the level of organic molecules and up, become hierarchical only in the presence of what the authors call ‘connection costs’. When there are no connection costs, claim the authors, these networks tend to develop flat structures (Mengistu et al. 2016). In other words, molecules, single-cell organisms and herds of mammals are just like the capitalists who own McDonald’s: they all self-organize to minimize their transaction costs in their quest for maximum gain.

With this in mind, should we trace the origins of capitalization back to Sumer? In my view, the answer is no:

- One of the distinguishing features of the capitalist mode of power is that power appears as a universal quantitative relationship between entities (relative prices). This feature first emerged in the early the European Bourgs and was later formalized by Johannes Kepler to describe the forces of the cosmos. In Sumer, powers (in plural) were stand-alone qualities. The idea that power was a universal quantitative relationship between entities was inconceivable.

- The “larger use of credit”, as Veblen called it, also a key feature of the capitalist mode of power, presupposes the growing universality of the price system. This condition did not exist in Sumer.

- Forward-looking capitalization is a derivative of the larger use of credit, again, inconceivable in Sumer

- Differential capitalization emerges from the wider use of capitalization, unimaginable in Sumer.

Of course, if you can show that these observations are false, or that tracing capitalization back to Sumer is indeed useful and revealing, I’ll withdraw these contestations.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

October 11, 2022 at 8:36 pm #248431

With this in mind, should we trace the origins of capitalization back to Sumer? In my view, the answer is no:

- One of the distinguishing features of the capitalist mode of power is that power appears as a universal quantitative relationship between entities (relative prices). This feature first emerged in the early the European Bourgs and was later formalized by Johannes Kepler to describe the forces of the cosmos. In Sumer, powers (in plural) were stand-alone qualities. The idea that power was a universal quantitative relationship between entities was inconceivable.

- The “larger use of credit”, as Veblen called it, also a key feature of the capitalist mode of power, presupposes the growing universality of the price system. This condition did not exist in Sumer.

- Forward-looking capitalization is a derivative of the larger use of credit, again, inconceivable in Sumer

- Differential capitalization emerges from the wider use of capitalization, unimaginable in Sumer.

Of course, if you can show that these observations are false, or that tracing capitalization back to Sumer is indeed useful and revealing, I’ll withdraw these contestations.

If evolutionary scientists can look to other primates for the origins of the human species, we can look to Sumer for the origins of capitalization (discounting future value to present values), and it is even more obvious why we can do so. Can we look to Sumer for origins of the capitalist mode of power in every detail? No. Sumer was missing a lot of essential ingredients for that. But can we look to Sumer for the origins of capitalization? Sure.

-

October 11, 2022 at 9:48 pm #248432

I came across a very interesting passage recently in a paper on virology. (I am not a virologist but I read papers in it from time to time.) It referred to self-assembly and coded assembly. The natural world exhibits features of both self-assembly and coded assembly at the level of life. Let us assume here that life begins at viruses. At the non-life and/or inorganic level, the natural world exhibits only self-assembly (where it is not exhibiting the plain old general cosmic process to ever greater entropy). A good example of self-assembly is the formation of a crystal under natural conditions. The paper I refer to states: “In the same way that a roll of magnets will spontaneously assemble together, capsid proteins also exhibit self-assembly. The first to show this were H. Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams in 1955. They separated the RNA genome from the protein subunits of tobacco mosaic virus, and when they put them back together in a test tube, infectious virions formed automatically. This indicated that no additional information is necessary to assemble a virus: the physical components will assemble spontaneously, primarily held together by electrostatic and hydrophobic forces.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7150055/ People on this forum may well assume at this point I am down an esoteric rabbit hole unrelated to political economy. I don’t entirely think so but it’s a long discussion and I’ve never succeeded in making my case. Suffice it to say, the task in political economy is in my view to stop looking for natural laws in political economy (aside from the natural laws involving the exothermic, endothermic and self-assembly reactions which we utilise in the real economy for inorganic production and the biological laws of (RNA and DNA) coded assembly we utilise in organic production like food and fibre production). At all levels above this, political economy is about complex human behaviours and encoded laws (i.e. legal laws, regulations, conventions, rituals etc.). This is my view which is obviously partially derived from CasP insights.

Rowan,

I made an off-hand reference to it earlier, but I am considering the possibility that hierarchies in human societies are self-assembling through the transmission of debt-based obligations, which include but are not limited to strictly monetary debts. Debt-based obligations are themselves a form of code that establish the senior party (e.g., the creditor or manager), the junior party (e.g., the debtor or subordinate), and the subject/object of their differential power (e.g., a loan of money at interest or a job). Capitalism is constructed of many level os debt-obligations, but so were prior modes of power.

One of the reasons I am looking well past the earliest date CasP assigns to the start of the capitalism (which I view as a few centuries too early) is to understand whether and how debt obligations worked differently in other modes of power. Again, I view western European feudalism as an aberration because it shunned finance as a state institution, whereas earlier modes of power were built around institutions that provided what were equivalent to (or at least analogous to) “financial” functions even in the absence of what we tend to view as money (e.g., coins and modern money).

-

October 11, 2022 at 11:32 pm #248433

1The future was deemed unknowable, subject to the whims of the gods.

At best, we have evidence of what elite Sumerians said in writing, but we don’t know what they actually thought or believed.

Today, neoclassical economic dogma essentially claims that the market is an all-seeing, all-knowing god that decides who wins and who loses. economically. Our future is unknowable because it is subject to the whims of the market.

But we know better because we can see how capitalists own and control the market, a fact that may not be so obvious far into the future, long after the age of capitalism has ended. Indeed, if humanity survives for another two thousand years, it is likely to view the theodicy of our capitalist era much as you view the theodicies of ancient civilizations such as Sumer.

-

October 12, 2022 at 6:04 am #248436

It seems to me that, with a sufficiently large sample, writing is a good indication for thinking.

Modern financial textbooks and highly-paid forecasters tell the future by combining expected earnings, assessments of risk and notions of normality. And the fact that capitalists bet on these written forecasts with their money suggests they do believe in what they pay for. Of course, these expensive forecasts, pronounced with stern faces and associated probabilities and aggregated into fancy publications such as consensus forecasts, are almost always wrong. But the reason they are wrong, claim the forecasters, is not that the future is unknowable, but that human beings refuse to obey the rational scriptures and end up walking randomly. But not to worry. There is now a new, innovative profession, formalized by straight-face behavioural financiers, that is busy predicting the external irrationality of us mortals in order to make the future whole again (think Ulf Martin’s autocatalytic sprawl).

Of course, we can never know for sure, but it seems to me that the ontology of the Sumerians, whose gods created humans to be their slaves, whose Anu was supreme authority and Enlil turbulence at will, whose ironclad rate of interest was religiously sanctified, and whose military conflicts were won and lost by competing gods, was very different.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

October 12, 2022 at 6:10 am #248438

Scot,

I’ve raised ideas which may or may not be useful in this discussion or even in CasP as a whole. But we have to be clear on definitions. In molecular biology, a clear distinction is made, as I understand it, between self-assembly and coded assembly. In self-assembly “no additional information” and thus no code is necessary to assemble a molecule, a conglomerate or an agglomerate of molecules [1]: “the physical components will assemble spontaneously, primarily (drawn and) held together by electrostatic and hydrophobic forces”. Assembly, from the operations of and on RNA and DNA, is termed coded assembly. Extra information, extra code as templates, is required and used for this more complex coded assembly. So what your refer to is coded assembly not self-assembly as defined here. I think it’s helpful to keep definitions consistent across the hard sciences and social sciences.

It follows from this that self-assembly is quite distinct from self-replication as coded assembly. Where “autocatalysis” fits into this schema I am not entirely sure but I may be able to attempt an educated guess. I mention “autocatalysis” precisely because some CasP theory does. See “The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery” by Ulf Martin. This paper also has sections on the development of money and banking IIRC but I am sure you have already read it. I refer to “autocatalysis” (and I refer to “power” too) because Ulf Martin follows a method of not just using physical science analogues for social science but of offering definitions which make the concept fully valid and operational in both contexts.

His definition of “power” illustrates this:

“Indeed, what is power? In the following, we try to develop a concept of power as the ability of persons to create particular formations against resistance.” This is a definition of power, referencing persons in this case, which one can see will be conformable to definitions of a person’s physical power or of his/her social power, capital power or even intellectual power, as examples.

Next, what is Martin’s definition of “autocatalytic”? He expressly offers:

“A single chemical reaction is said to be autocatalytic if one of the reaction products is also a catalyst for the same or a coupled reaction.’ (Wikipedia 2018). If we carry this definition over to the social symbolic machinery, we can say that credit creation is an autocatalytic process, a process that feeds itself.”

An even better definition may be (and I am no expert in chemistry):

“A single chemical reaction is said to be autocatalytic if one of the reaction products is also a catalyst or a reactant for the same or a coupled reaction.”

Martin goes on to write:

If we carry this definition over to the social symbolic machinery (of finance and capital) , we can say that credit creation is an autocatalytic process, a process that feeds itself.”

I am very keen on demonstrating that real system / formal system ontology can be unified and that the links so delineated are more than just analogies. Rather, I am trying to posit and demonstrate (if I ever can) that in a priority monist system as a fully interrelated complex system of systems (which I hold the universe or cosmos to be) that such links (between real and formal systems) are tightly homomorphic, not just analogous, and governed by the same basic principles in relation to matter, energy and especially information. A tall order I know. I will try to distil something and post on it, maybe for debate, to see if I can generate interest here.

But on topic, we must eventually talk about, I assert, self-replicating coded assembly incorporating autocatalysis (following Ulf Martin’s lead) at the formal systems level. Real systems and formal systems share matter, energy and information. Information is instantiated in media as patterns. Formal systems, at least successful and efficient formal systems, will demonstrate, I propose, a relatively high information content to matter / energy ratio. This will be a necessary but not sufficient condition for a successful, self-promulgating or self-replicating formal coded assembly system incorporating autocatalysis. In relation to “dupable” humans, information may also be misinformation and disinformation. It is only in relation to operations on real systems at fundamental physical law levels that misinformation and disinformation result in rapid, proximal failures, accidents and catastrophes. In relation to operations on and in formal systems, misinformation and disinformation, especially if expanding exponentially, appear at first indefinitely sustainable but lead in the end to delayed but exacerbated failures, accidents and catastrophes of vast scope.

Note 1: A conglomerate is a collection of related items. An agglomerate is a collection of unrelated items. The naming of a collection or grouping as a conglomerate or an agglomerate could actually depend on the observer’s category decisions as categories define or describe relations.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Rowan Pryor.

-

October 12, 2022 at 1:48 pm #248440

Of course, we can never know for sure, but it seems to me that the ontology of the Sumerians, whose gods created humans to be their slaves, whose Anu was supreme authority and Enlil turbulence at will, whose ironclad rate of interest was religiously sanctified, and whose military conflicts were won and lost by competing gods, was very different.

So what you are saying is that Sumer had a “risk free” rate of return (i.e., the financial benchmark of an ironclad rate of interest that was religiously sanctified) for loans collateralized by land and the person of the debtor (and the persons of his kin, most likely).

Kidding aside, I really don’t know why you have fixated on Sumer (you brought it up, not me) to dismiss the possibility that capitalization (discounting) predates capitalism by potentially thousands of years. I was thinking specifically of Ancient Athens and the Roman Republic when I suggested the possibility, but hey, Sumer.

-

October 12, 2022 at 3:57 pm #248441

Let’s leave Sumer aside.

Did capitalization — not interest or other future payments, which, on their own do not imply capitalization — start in Ancient Athens and the Roman Republic? Is this where the 13-14th Century European burgers picked the idea from?

That would be an interesting study to read.

-

October 12, 2022 at 6:13 pm #248442

I am not sure if I am adding anything to this discussion. However, I think we should be clear on definitions. The first steps in any academic argument must be to agree on (a) a priori assumptions and (b) definitions of terms. Leaving aside a priori assumptions for the moment (for we can’t even expose and examine a priori assumptions without agreed terms) [1], what are our definitions of capitalism, capital and capitalization?

1. Capitalism

Is the Wikipedia definition for Capitalism serviceable here? “Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private property, property rights recognition, voluntary exchange, and wage labor. In a market economy, decision-making and investments are determined by owners of wealth, property, or ability to manoeuvre capital or production ability in capital and financial markets—whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.”

When we look at the Wikipedia definition in Wikipedia, we note that a whole list of terms in this definition have color-highlighted. underlined links. These further definitions are essential ingredients to understanding the “capitalism” definition. I’ve sometimes been faced by arguments that capitalism is non-existent, as a system, because it is not pure and not ubiquitous. The biggest plum pulled out of this magic pudding is the mixed economy argument. This argument is much like saying policing does not exist because it is not pure and not ubiquitous.

It is now commonly asserted that capitalism is a global system. I concur. This is despite the fact that it is not pure and not ubiquitous. Purity and ubiquity are not possible for any finite system in the cosmos or in the world. Any system is always embedded in something that is “all systems together” (the monistic totality) and we can always note combinations, conglomerates, agglomerates. The best analogy (and it is not just an analogy but a monistic homomorphic congruence) is a net. Capitalism extends its net, of connections, and (dynamically) nets the world. It hasn’t netted the whole world. Small stuff gets through. Big stuff breaks through, tears the net. But ever the net is expanded, repaired, meshed out autocatalytically, to use Ulf Martin’s applied term. Ultimately, large fundamental forces can (and will) “explode” the net or rapidly unravel the net but that is another topic. Looking back in time (which is more the issue here), we can nominate capitalism’s starting point, with an agreed comprehensive definition of capitalism.

2. Capital

Next we get to the definition of “capital”. Here, “CasP (Capital as Power) already has a problem with classical economics encompassing capitalist economics and Marxist economics.

Note 1 – And our agreed terms can already contain unexamined a priori assumptions. How do we deal with that? I would argue that we can only do that iteratively, after provisionally agreeing on terms, by then examining the set of currently agreed terms, currently agreed principles and currently agreed methods. Thence we find anomalies (internal inconsistencies) and lacunae and then resolve them if possible. We keep trying to iron out and mend our investigative system out until we agree we can find no more wrinkles and no more holes, for the present at least. Then we apply it to the real world for the necessary empirical testing.

-

October 12, 2022 at 10:12 pm #248443

I am not sure if I am adding anything to this discussion. However, I think we should be clear on definitions. The first steps in any academic argument must be to agree on (a) a priori assumptions and (b) definitions of terms. Leaving aside a priori assumptions for the moment (for we can’t even expose and examine a priori assumptions without agreed terms) [1], what are our definitions of capitalism, capital and capitalization? 1. Capitalism Is the Wikipedia definition for Capitalism serviceable here? “Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private property, property rights recognition, voluntary exchange, and wage labor. In a market economy, decision-making and investments are determined by owners of wealth, property, or ability to manoeuvre capital or production ability in capital and financial markets—whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.” When we look at the Wikipedia definition in Wikipedia, we note that a whole list of terms in this definition have color-highlighted. underlined links. These further definitions are essential ingredients to understanding the “capitalism” definition. I’ve sometimes been faced by arguments that capitalism is non-existent, as a system, because it is not pure and not ubiquitous. The biggest plum pulled out of this magic pudding is the mixed economy argument. This argument is much like saying policing does not exist because it is not pure and not ubiquitous. It is now commonly asserted that capitalism is a global system. I concur. This is despite the fact that it is not pure and not ubiquitous. Purity and ubiquity are not possible for any finite system in the cosmos or in the world. Any system is always embedded in something that is “all systems together” (the monistic totality) and we can always note combinations, conglomerates, agglomerates. The best analogy (and it is not just an analogy but a monistic homomorphic congruence) is a net. Capitalism extends its net, of connections, and (dynamically) nets the world. It hasn’t netted the whole world. Small stuff gets through. Big stuff breaks through, tears the net. But ever the net is expanded, repaired, meshed out autocatalytically, to use Ulf Martin’s applied term. Ultimately, large fundamental forces can (and will) “explode” the net or rapidly unravel the net but that is another topic. Looking back in time (which is more the issue here), we can nominate capitalism’s starting point, with an agreed comprehensive definition of capitalism. 2. Capital Next we get to the definition of “capital”. Here, “CasP (Capital as Power) already has a problem with classical economics encompassing capitalist economics and Marxist economics. Note 1 – And our agreed terms can already contain unexamined a priori assumptions. How do we deal with that? I would argue that we can only do that iteratively, after provisionally agreeing on terms, by then examining the set of currently agreed terms, currently agreed principles and currently agreed methods. Thence we find anomalies (internal inconsistencies) and lacunae and then resolve them if possible. We keep trying to iron out and mend our investigative system out until we agree we can find no more wrinkles and no more holes, for the present at least. Then we apply it to the real world for the necessary empirical testing.

Thanks, Rowan.

The point of contention here is not the definition of capital, capitalism, or even capitalization, it is the origins and terminus a quo of capitalization (its earliest start date). Jonathan and I agree that capitalization was established “as the heart of the capitalist nomos” some time in the second half of the 20th century (Bichler and Nitzan say by the 1950s, but I place it in the 1960s after the publication of Miller’s and Modigliani’s “Dividend Policy, Growth, and the Valuation of Shares ” in 1961). See p. 158 of Capital as Power (2009).

Bichler and Nitzan find the origins and terminus a quo of capitalization in fourteenth century Italy:

Simple computations in this spirit were used as early as the fourteenth century. Italian merchants allowed customers to pre-pay their bills at a ‘discount’, applying the rate of interest to the time left until payment was due. Initially, the practice was relatively limited.

Capital as Power (2009) at p. 155 (citing Faulhaber’s and Baumol’s “Economists as Innovators: Practical Products of Theoretical Research” at pages 583-584

By “bill,” Bichler and Nitzan are referring to a bill of exchange, not what we think of as a bill today, which is just an invoice from the seller to the buyer. A bill of exchange is a financial instrument (contract) that simulates a short term loan at interest by having a price equal to the principal plus all interest due at the end of the term. By “merchant,” Jonathan is referring to the holder of the bill of exchange, which by the end of the term may or not be the merchant who sold the merchandise in exchange for the bill of exchange (which was presented by the buyer’s agent to the merchant, not by the merchant to the buyer).

If the merchant had actually made a loan at interest, early payment of the loan would automatically exclude any interest that had not accrued because it was not due, i.e., “discounting” is automatic for the early payment of a loan, but not for a bill of exchange. Merchants who had accepted the buyer’s bill (i.e., his unsecured promise to pay) and agreed to discount a bill were merely honoring the underlying intent of the contract by foregoing interest that would not have been due but for the form of the loan.

For whatever reason, Bichler and Nitzan privilege this form of discounting as being in the “spirit” of his capitalization formula, presented at pages 153-155 of Capital as Power (2009), while seemingly ignoring others. But you don’t actually need their (or any) version of the capitalization (discounting) formula to provide this type of discount, all you have to do is calculate the interest due at the time of early payment, subtract it and the principal amount from the par value of the bill, and that is your discount. Ta daaa.

In some ways, I am both more and less demanding of what the earliest example of capitalization could be. I don’t think it should be limited to simulating the early payment of an unsecured loan, as Bichler’s and Nitzan’s example is, because that does not capture anything that looks like buying and selling shares on a stock exchange, upon which CasP theorists focus with rare exception. The key is at risk future income, regardless of how that future income is expressed (e.g., whether as profits or interest).

The earliest and closest analog to contracts to purchase future income (as opposed to just making an loan or simulation of one) of which I am currently aware is tax farm contracts in which a private party purchased the right to collect tithes/taxes from defined territories of the state (i.e., the farm), typically for a set term of years (e.g., 5 years). Hammurabi employed tax farmers. So did the Ptolemies of Egypt and the aristocrats of the Roman Republic.

In Rome, tax farm contracts were put up for auction (you know, sold on a market), and applicants bid on the contracts. The winning bid got the contract, and the Roman Republic received money equal to the winning bid as full payment for any taxes the bidder might recover. Tax farmers kept all taxes/tithes they recovered, and it turns out that tax farm contracts were extremely profitable, so one would think there was some form of discounting (capitalization) going on. Interestingly, the buyers of tax farm contracts were often the Roman equivalent of a corporation with shareholders. But, hey, Sumer. Nothing to see here.

I am currently reading James Tan’s 2017 book about Roman tax farming (among other things), entitled Power and Public Finance at Rome, 264-49 BCE. The book focuses on how Roman aristocrats of the Republic era relied on tax farming to keep the state weak while enriching themselves and keeping their aristocratic rivals at bay. The decentralized aspects of Rome’s mode of power (the Roman republic served its aristocrats, not the other way around) disappeared when Julius Caesar seized power and effectively became the state.

As interesting as I find all this, it is tangential to my original post in which I queried whether wages are priced in a manner that capitalizes labor’s contribution to the at-risk income. I feel confident that is the case today because the typical response to seeing 15% of profits evaporate in the present and the future is to layoff 15% of the wages (they don’t really think in terms of other human beings).

If you want, I would be happy to share copies of the journal papers I cite above. Just let me know.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Scot Griffin. Reason: added formatting to quote

-

October 13, 2022 at 7:07 pm #248446

Thank you Scot.

I read Chapter 2 in Tan’s book, ‘The Use and Abuse of Tax Farming’, and found it really interesting. What I didn’t find, though, is any evidence that tax farmers discounted future earnings — in Rome and elsewhere.

In your post, you write that

Tax farmers kept all taxes/tithes they recovered, and it turns out that tax farm contracts were extremely profitable, so one would think there was some form of discounting (capitalization) going on.

Well, from Ch. 2 in Tan’s book it seems that historians of tax farming know relatively little, if anything, about the profitability of tax farmers. One guesstimate puts the rate of profit of Roman publicani in a certain region between 8-215%, while another speculates it was 30% (pp. 57-8). But no one really knows.

Similarly, judging by this chapter, nobody knows what calculations contract bidding was based on. The chapter does not mention discounting/capitalization of future earnings, let alone offers any evidence that such discounting/capitalization took place.

Reading between Tan’s lines, my impression (again, nobody really knows) is that contract bidding was largely a matter of arms wrestling. When the tax farmers overcame their mutual disdain and acted in unison, prices were low and they could make a bundle; when they bickered, prices were high and they earned little or even lost (and sometimes demanded retroactive rebates, no less). There was no need for any risk coefficients and raising the normal rate of return to the power of five. It was simply a matter of strongmen groping for what the ‘Republic will bear’.

This isn’t an area I know enough about, and there may be other studies where discounting of tax farming is discussed and assessed. But without such evidence, the claim that these contracts reflected discounting seems to me unsubstantiated.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

October 13, 2022 at 4:32 pm #248445

Scott,

I got off topic and I didn’t manage to circle back to your topic. Mea culpa. I am questioning empirical ontology (as it affects the hard and social sciences) at a more fundamental level, or so I think. I may be a “crank” in Blair Fix’s definition of the term as per his excellent and amusing article “How Do You Spot a Crank?”. What I need to do, if I want to pursue it, is post my simplest explication of my system of enquiry, in this forum. Whether it makes sense, to anyone, will be the issue. If people like Jonathan and Blair responded “you are completely off course”, I would certainly pay attention to that.

-

October 30, 2022 at 5:49 pm #248492

Thank you Scot. I read Chapter 2 in Tan’s book, ‘The Use and Abuse of Tax Farming’, and found it really interesting. What I didn’t find, though, is any evidence that tax farmers discounted future earnings — in Rome and elsewhere. In your post, you write that

Tax farmers kept all taxes/tithes they recovered, and it turns out that tax farm contracts were extremely profitable, so one would think there was some form of discounting (capitalization) going on.

Well, from Ch. 2 in Tan’s book it seems that historians of tax farming know relatively little, if anything, about the profitability of tax farmers. One guesstimate puts the rate of profit of Roman publicani in a certain region between 8-215%, while another speculates it was 30% (pp. 57-8). But no one really knows. Similarly, judging by this chapter, nobody knows what calculations contract bidding was based on. The chapter does not mention discounting/capitalization of future earnings, let alone offers any evidence that such discounting/capitalization took place. Reading between Tan’s lines, my impression (again, nobody really knows) is that contract bidding was largely a matter of arms wrestling. When the tax farmers overcame their mutual disdain and acted in unison, prices were low and they could make a bundle; when they bickered, prices were high and they earned little or even lost (and sometimes demanded retroactive rebates, no less). There was no need for any risk coefficients and raising the normal rate of return to the power of five. It was simply a matter of strongmen groping for what the ‘Republic will bear’. This isn’t an area I know enough about, and there may be other studies where discounting of tax farming is discussed and assessed. But without such evidence, the claim that these contracts reflected discounting seems to me unsubstantiated.

Jonathan,

Here is a link to a 1977 article by Roger Bagnall entitled “Prices in ‘Sales on Delivery'” from the journal of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies.

The transaction Bagnall describes at pages 91-92, which occurred in the 4th century CE, is similar to a medieval bill of exchange, i.e., a disguised loan at interest, but the money is delivered before the goods. The interest (or discount) rate (r) is 50%, resulting in a discounting of the price of the goods at the time of delivery by 33%. Implicitly, according to Bagnall, the 4th century lender appears to have calculated the discount (d) of 33% using the discounting formula, or its equivalent, that Faulhauber and Baumol claim Italian merchants invented in the 14th century CE, i.e., d = r/(1+r); when r = 50%, d = 33%.

At page 287 of his 2013 book The Roman Market Economy, Peter Temin cites to the Bagnall article to argue that such contracts were used in Rome in the 3rd century BCE.

Please review and let me know what you think. Thanks.

-

November 2, 2022 at 8:06 am #248518

Bagnall’s text is intended for the specialist, and I find it really hard to follow. I do understand, though, that:

1. The discussion involves fragmented ancient evidence that the experts piece together, fill the in-between blanks and then interpret the results as if they were modern financial transactions.

2. The transactions involved aren’t purely monetary, but hybrids of money and ‘in-kind’ flows. This mix means that even when the transactions are clearly stated — and most aren’t — their underlying magnitudes are only partly specified:

We can now summarize the types of transactions involved in the Tetoueis documents and the new Berlin text: (1) loans in kind to be repaid in kind with interest of 50 per cent ;20 (2) loans in money to be repaid in kind, with both amounts specified but not the interest; (3) loans in money, amount specified, to be repaid in kind at a price not specified but reduced by a third; (4) loans in money, with amount not specified, to be repaid with a fixed amount of produce. (Bagnall: 93)

With this in mind, interpreting the ‘pricing’ of these contracts as if they were acts of capitalization, however embryonic, seems to me far fetched.

- This reply was modified 2 years, 8 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

November 6, 2022 at 9:58 pm #248550

Bagnall’s text is intended for the specialist, and I find it really hard to follow. I do understand, though, that: 1. The discussion involves fragmented ancient evidence that the experts piece together, fill the in-between blanks and then interpret the results as if they were modern financial transactions. 2. The transactions involved aren’t purely monetary, but hybrids of money and ‘in-kind’ flows. This mix means that even when the transactions are clearly stated — and most aren’t — their underlying magnitudes are only partly specified:

We can now summarize the types of transactions involved in the Tetoueis documents and the new Berlin text: (1) loans in kind to be repaid in kind with interest of 50 per cent ;20 (2) loans in money to be repaid in kind, with both amounts specified but not the interest; (3) loans in money, amount specified, to be repaid in kind at a price not specified but reduced by a third; (4) loans in money, with amount not specified, to be repaid with a fixed amount of produce. (Bagnall: 93)

With this in mind, interpreting the ‘pricing’ of these contracts as if they were acts of capitalization, however embryonic, seems to me far fetched.Thank you for reviewing and responding.

As I see it, medieval bills of exchange were just supply on demand contracts in reverse. Both types of agreements involved disguised interest-bearing loans made in connection with the sale of goods in which the delivery of the money and the goods differ in time. For medieval bills of exchange, the goods are delivered today in exchange for payment at a later time subject to interest. For the sale on delivery contract, the money is delivered first, and the sale price of the goods delivered at a later time is discounted by a discount rate (at least that is what Bagnall argues). As a result, the face value of a sale on delivery contract is the present value of a future transaction discounted for risk (the discount rate). If Bagnall is correct, discounting was known at least as early as the 4th century CE, and others argue that it was known much earlier.

NOTE: Faulhauber and Baumol, upon whom you rely at page 155 of Capital as Power (2009), seem to misunderstand the nature of medieval bills of exchange. It is not true that “Italian merchants allowed customers to pre-pay their bills at a ‘discount’, applying the rate of interest to the time left until payment was due.” The amount of the bill of exchange remained fixed, due and payable by the customer. The discounting occurred between the merchant and the exchange bankers, allowing the merchant to receive payment and the exchange bankers to enjoy the mark-up as payment and trade bills amongst themselves in settlement of debts. See Colin Drumm’s discussion on his substack.

Whether discounting is always capitalization is a separate question. The “after market” of bills of exchange may be a valid basis for viewing only the discounting of bills of exchange as capitalization and not supply on delivery contracts, given the apparent absence of such an after market for supply on demand contracts. Still, supply on demand contracts used the discounting formula directly in the pricing of the exchange and, more likely than not, the buyer realized income by selling the goods he purchased for more than the discounted price for which he purchased them. Value is value because money makes it so.

-

November 7, 2022 at 9:51 pm #248555

If capitalization is the only pricing mechanism in capitalism, this would imply that what Marx calls exchange value is, in fact, just discounted use value, i.e., exchange value is capitalized use value.

Why do you say that discounting capitalizes use value (rather than power)?

Jonathan,

I’ve taken the time to distill down the observation that inspired my original comment from the unnecessary confusion of use value/exchange value, Sumer, etc.

Basically, my question was “are commodities, including labor, priced the same way as capital assets”? Originally, I thought of mark-up as entailing the arbitrary addition of desired profits to costs, but based on equations 3-6 below, it seems we can model wages paid to labor as the present value of future profits accruing to the benefit of capitalists, discounted for risk. This “discovery” is so obvious in hindsight that it probably isn’t new to anyone else here.

The reason I bothered referring to Marx at all is because of the concepts of use value, exchange value, and surplus don’t seem to account for time and risk. When viewed through the lens of compounding/discounting, value is either in the past/present, or it is in the future, and there is no surplus, only discounting or compounding based on the perception of risk. “Mark-up” is really the the allocation of rewards based on who takes the risks (at least that is what a capitalist might argue), and there is really no value outside of that.

I don’t think this view of how prices are set affects CasP theory negatively because, after all, setting the discount rate is a pretty straightforward assertion of power, as is rendering people unable to object to the allocation of rewards (e.g., through structural violence that requires labor to accept the wages offered or cease to exist).

I will leave it to you to determine whether this instance of discounting is an example of capitalization, but I provide some thoughts below. Now to the analysis.

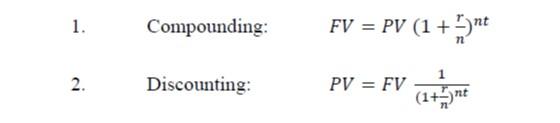

Beginning with the basic formulas for compounding and discounting, where FV is future value and PV is present value:

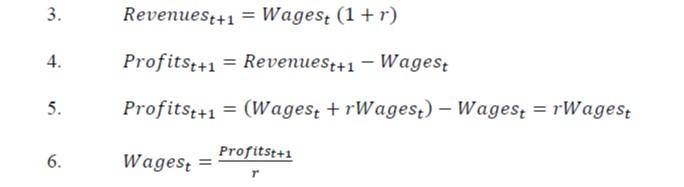

Assuming n=1, t=1, wages paid to labor today (Wagest) are the only input costs associated with revenues generated by the future sale of commodities produced by said labor (Revenuest+1), and the capitalist expects a rate of return r from the future sale of said commodities, we can express Revenuest+1 as the expected FV of Wagest (PV) using the simplified compounding formula:

Equation 6 is the same form as the capitalization formula (5) found at the bottom of page 154 of Capital as Power (2009). Thus, wages paid to labor today can be viewed properly as the “risk-adjusted discounted value of expected future earnings” (i.e., Profitst+1), i.e., wages can be viewed as the capitalization of expected profits (or power, if you would prefer). As you’ve said, “capitalization represents the present value of a future stream of earnings: it tells us how much a capitalist would be prepared to pay now to receive a flow of money later.” Capital as Power, at p. 153.

Of course, unlike stocks and bonds, there is no distinct property right associated with the payment of wages, i.e., when a capitalist pays wages, he is not acquiring a capital asset that is distinct from his business. However, the capitalist already owns the business that owns the products produced by the labor paid for by the wages, and, therefore, the capitalist is entitled to the income stream arising from the sale of said products. The capitalist pays wages to secure a future income stream, and the capitalist sets wages by discounting that future income to a present value adjusted for risk.

-

November 10, 2022 at 1:01 pm #248571

Thank you for both posts, Scot.

In our book Capital as Power, we describe the ever-growing terrain of capitalization:

Nowadays, every expected income stream is a fair candidate for capitalization. And since income streams are generated by social entities, processes, organizations and institutions, we end up with the ‘capitalization of every thing’. Capitalists routinely discount human life, including its genetic code and social habits; they discount organized institutions from education and entertainment to religion and the law; they discount voluntary social networks; they discount urban violence, civil war and international conflict; they even discount the environmental future of humanity. Nothing seems to escape the piercing eye of capitalization: if it generates earning expectations it must have a price, and the algorithm that gives future earnings a price is capitalization. (158)

Extrapolating the foregoing illustrations, we can say that in capitalism most social processes are capitalized, directly or indirectly. Every process – whether focused on the individual, societal or ecological levels – impacts the level and pattern of capitalist earnings. And when earnings get capitalized, the processes that underlie them get integrated into the numerical architecture of capital. Moreover, no matter how varied the underlying processes, their integration is always uniform: capitalization, by its very nature, converts and reduces qualitatively different aspects of social life into universal quantities of money prices. In this way, individual ‘preferences’ and the human genome, the structure of persuasion and the use of force, the legal structure and the social impact of the environment – are qualitatively incomparable yet quantitatively comparable. The capitalist nomos gives every one of them a present value denominated in dollars and cents, and prices are always commensurate. (166)

With this being said, I think we need to distinguish ‘actual capitalization’ from ‘as-if capitalization’.

As Ulf Martin explains, capitalization is an ‘operational symbol’ – namely, a symbol that does not simply represent the reality, but explicitly defines and creates it in the first place. And, to me, this feature suggests that for something to be labeled capitalization, it needs to be consciously articulated as such.

In this context, we can think of ‘actual capitalization’ as one that the capitalizer explicitly spells out; as-if capitalization as one that the outside observer-theorist imposes; and in-between cases as weighed by their proximity to either pole.

A wage payment in this scheme is actual capitalization if the capitalists and workers involved calculate it as such, but it is only as-if capitalization if the idea is merely imposed by the outside observer-theorist.

And in my opinion, the same goes for discoveries of ‘ancient capitalization’: unless we can demonstrate that the price was consciously or at least explicitly articulated by the price setter as the discounting of expected further earnings, it remains a retrospective, as-if imposition.

***

Martin, Ulf. 2019. The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery. Review of Capital as Power 1 (4, May): 1-30.

-

November 10, 2022 at 6:45 pm #248574

With this being said, I think we need to distinguish ‘actual capitalization’ from ‘as-if capitalization’. As Ulf Martin explains, capitalization is an ‘operational symbol’ – namely, a symbol that does not simply represent the reality, but explicitly defines and creates it in the first place. And, to me, this feature suggests that for something to be labeled capitalization, it needs to be consciously articulated as such. In this context, we can think of ‘actual capitalization’ as one that the capitalizer explicitly spells out; as-if capitalization as one that the outside observer-theorist imposes; and in-between cases as weighed by their proximity to either pole. A wage payment in this scheme is actual capitalization if the capitalists and workers involved calculate it as such, but it is only as-if capitalization if the idea is merely imposed by the outside observer-theorist. And in my opinion, the same goes for discoveries of ‘ancient capitalization’: unless we can demonstrate that the price was consciously or at least explicitly articulated by the price setter as the discounting of expected further earnings, it remains a retrospective, as-if imposition. *** Martin, Ulf. 2019. The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery. Review of Capital as Power 1 (4, May): 1-30.

What you describe as “as-if capitalization” is a type of presentism, a fallacy that is often unwittingly embraced by those dealing with history, and I agree we need to be careful to avoid that.

As I allude to in my last two replies, I do not believe that discounting and capitalization are one and the same, and part of what I am trying to explore here is, if discounting is not necessarily capitalization, what distinguishes capitalization from merely discounting?

I am not quite ready to agree that consciousness of or explicit reference to discounting in the process of price-setting is enough for there to be capitalization, which means I don’t necessarily agree that the discounting of medieval bills of exchange was capitalization. The example used by Faulhauber and Baumol just applied a pro rata allocation of the bill’s mark-up (r/1+r) to determine what interest had already accrued and was due to the holder at the time he sold the bill of exchange. The buyer and seller were just allocating the principal and already accrued mark-up of the bill to the seller and the remainder of the mark-up to the buyer (who would have recourse for the entire amount of the bill if the debtor failed to pay).

I do think the existence and use of medieval bills of exchange caused merchants to become conscious of compounding and discounting and incorporate it into how they priced wages and goods, but that process may have already been underway in agrarian England as reflected by the enclosure of the commons to increase yields (I have found some scholars who seem to argue that the discussion of “yields” really refers to the rate of financial return to the landowner, not necessarily to increased rate of production of the commodity on enclosed land).

-

November 10, 2022 at 7:48 pm #248575

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.