- This topic has 11 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated December 24, 2020 at 12:09 am by .

-

Topic

-

November 24, 2020: In a bizarre 90-second press conference about the rise of the Dow Jones Industrial, Trump notes that the index passed a “sacred” number: 30,000.

Like so much of the Trump presidency, we can talk about Trump’s vainglory. As much as it would be fun to let loose in that type of conversation–especially because his ego is a bruised apple at this point–I think that we can transform Trump’s praise of stock market milestones into broader questions related to political economy. I can think of a few, but I am sure there are more:

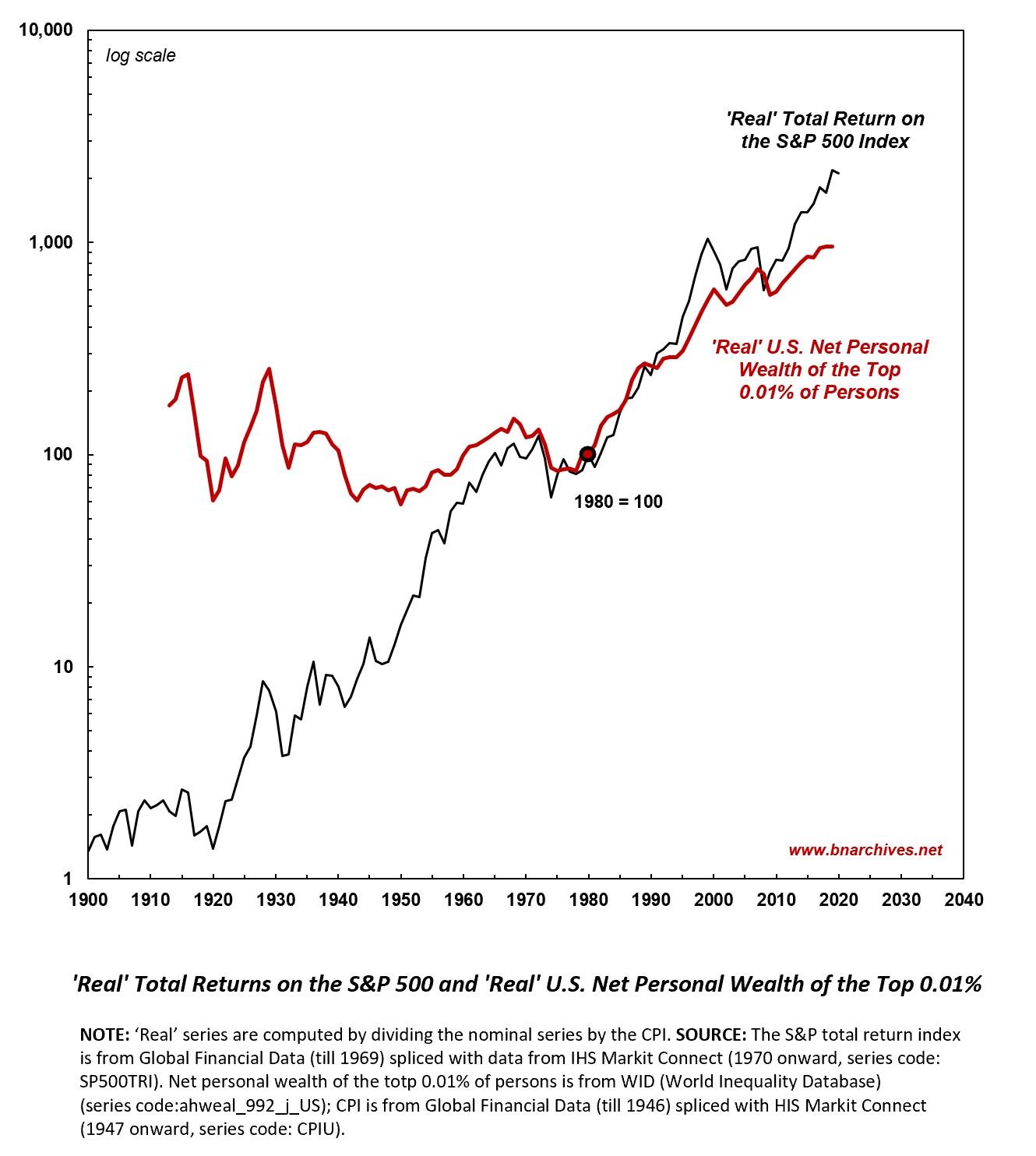

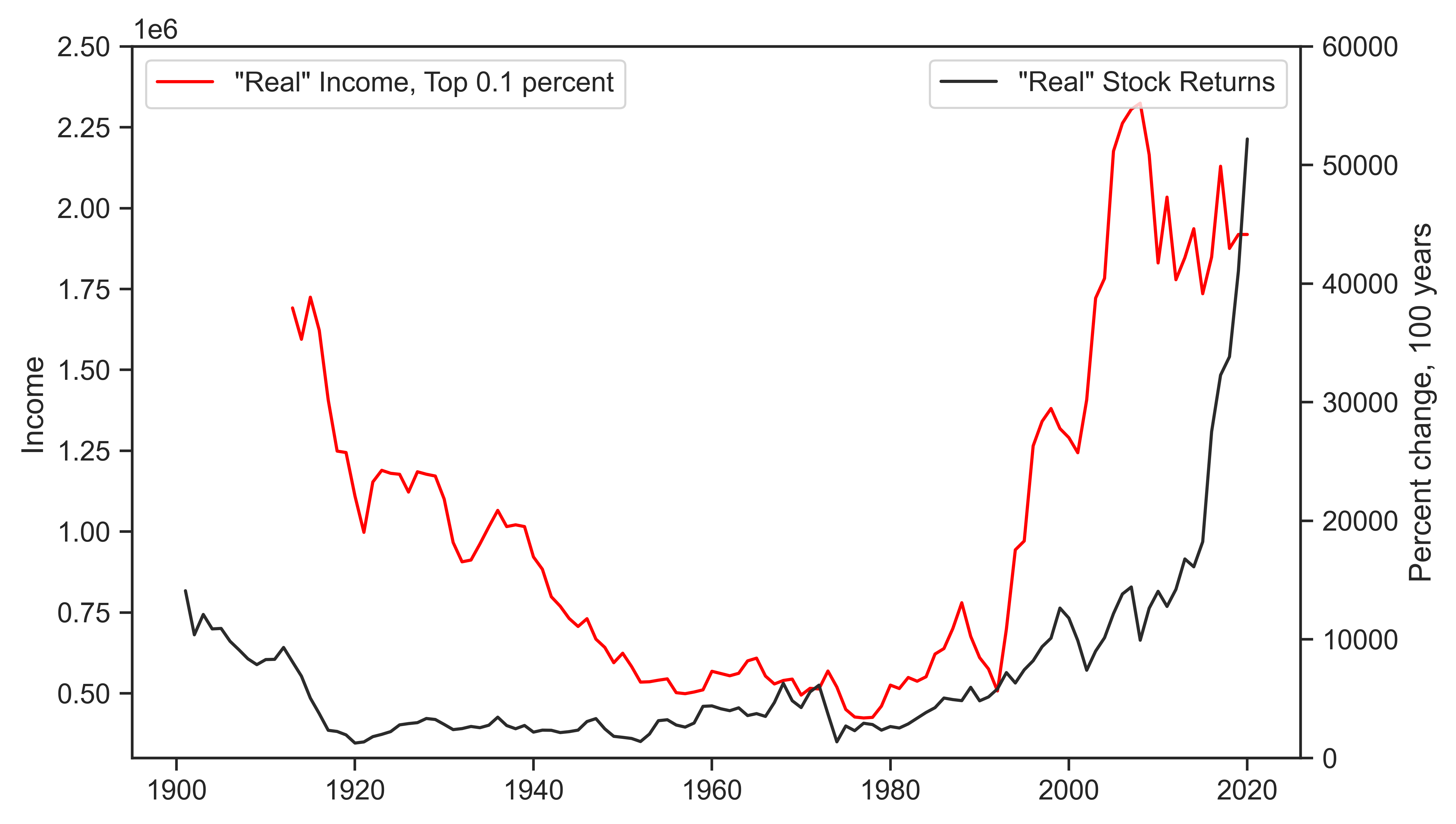

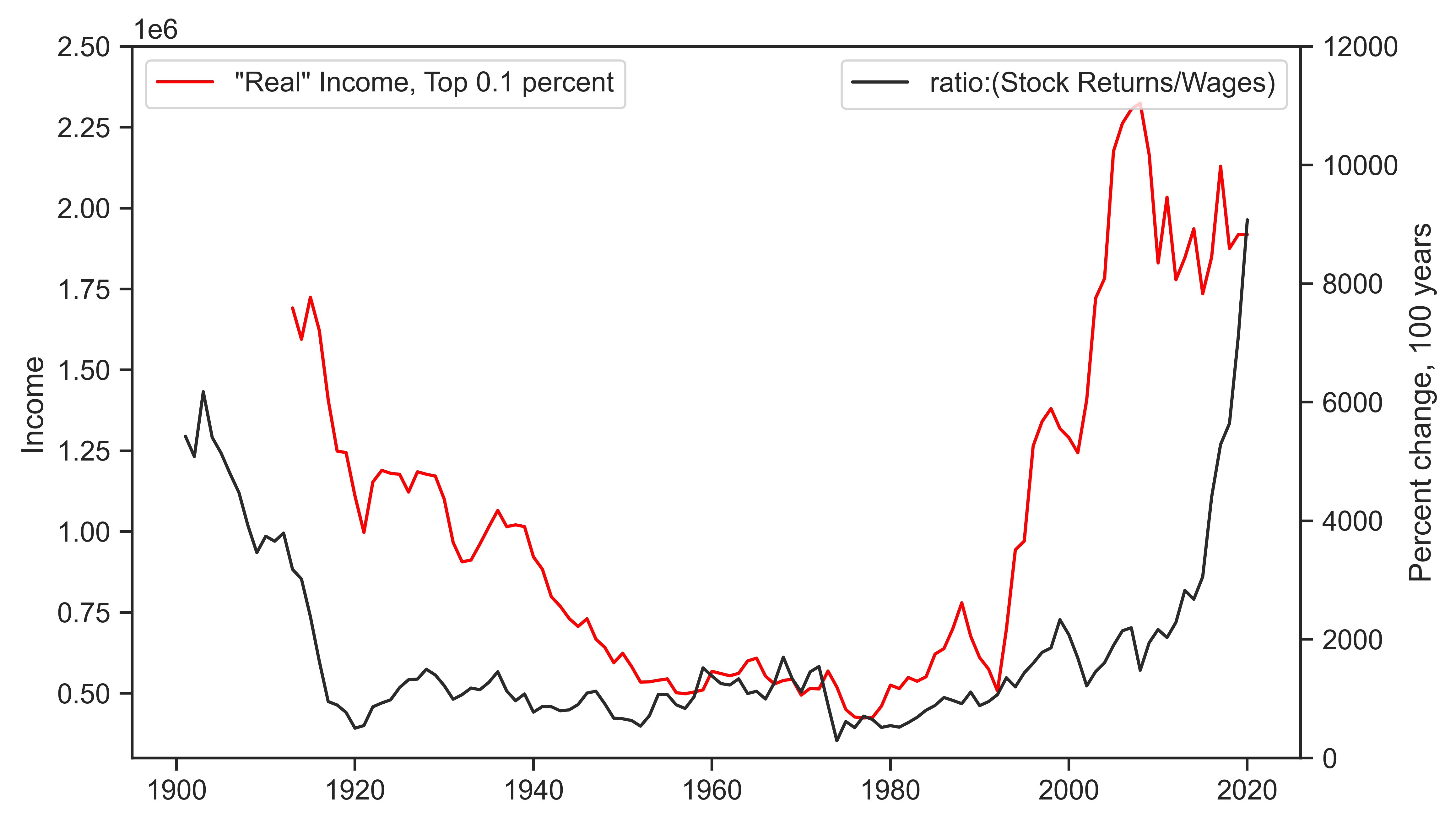

A) What does an elected politician think the stock market represents to their audience? Do they believe the everyday citizen will (mis)understand what stock market gains mean? Is Trump speaking directly to the Buffet’s and Bezos’ of the world, essentially saying he has been good for dominant capital?

B) Are there other memorable examples of politicians theatrically praising stock market rises? Outside of the United States? Is this more of an American custom because of indices like the Dow Jones and the S&P 500?

C) Should we be critical of how retorts to Trump’s praises of the stock market–e.g. stock markets rose more during Obama’s presidency–will often accept a naive meaning of a stock market index. Does this type of response fall into the trap of using the stock market as a barometer of social benefits and overall wealth?

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.