- This topic has 28 replies, 7 voices, and was last updated June 25, 2021 at 7:32 pm by .

-

Topic

-

Hi! I have a question about corporation and the so-called “corporate governance” and how it can be seen through the lens of CasP.

I have been reading <Capital as Power> for some time and I find the book very informative and interesting! I agree with a lot of the authors’ conceptualization of capitalism and their critique of other schools of economics (neoclassical and Marxist).

I agree that capital is power. Yet I think it’s also worthwhile to think about and recognize the exact mechanisms through which the power manifests itself in society. Specifically (perhaps because I am a law student) I think (certainly not *all*, but) most power takes the form of legal rights that has actual enforceability against others. This point was illustrated by Katharina Pistor in her book <The Code of Capital> – what capital as a legal right has: 1) priority (ranking competing claims) 2) durability (extending priority claims in time) 3) universality (extending in space) 4) convertibility (of said rights into state money on demand). (https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691178974/the-code-of-capital). Perhaps it would be worthwhile to try to connect CasP with this “law’s coding of capital” view – but this would be for next time!

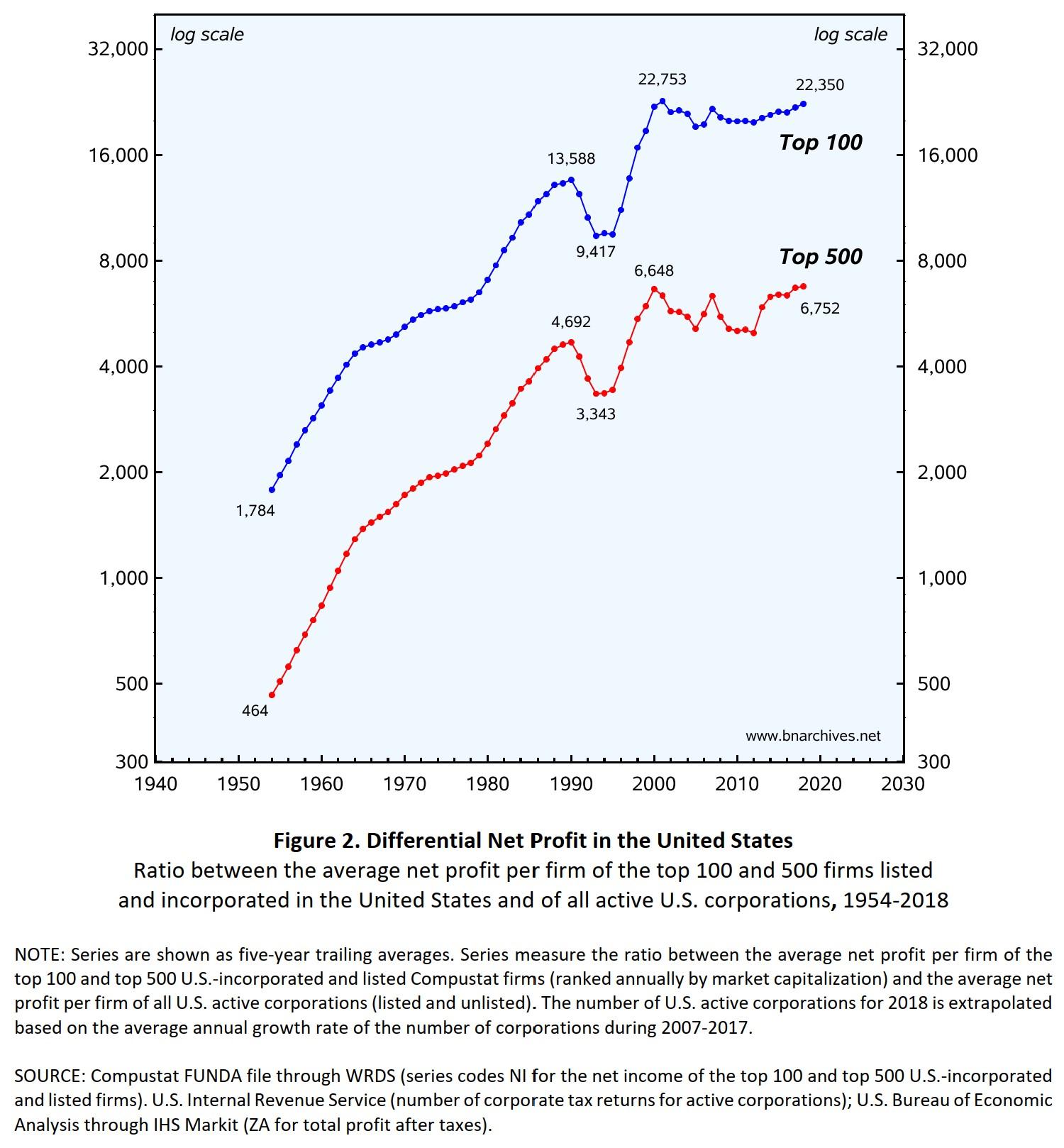

So, I think the mechanism and operation of the manifestation of power and its structure in society is interesting and important. And I think, in that regard, the corporate system is important. As the CasP book noted, it’s where differential accumulation happens. It’s also where , indeed, like it or not, most of our social and economic activities, including employment, production of consumption goods happen.

What the corporate law academia (and some industrial organization economics – at least my understanding is) identifies as the key issue of corporation is a bundle of questions regarding the so-called “corporate governance“: 1) what is a corporation – and does it have a “purpose”? 2) should it serve the society in general? 3) to achieve 2), how the ownership/control should change?

These questions are important, since the identification and classification of the “fiduciary duties” of officers or directors at a company tend to depend on how the court and the academia have interpreted them, and depending on circumstances, decisions of these power-holders can be actionable: they may constitute a breach of their duties and then shareholders can claim liability – or in worst cases they might be charged with malfeasance. I think the interpretation of these matters does have real-world effects (by shaping and constraining decision-making.

(I have to clarify that, in some common law jurisdictions, including the United States, the Court has developed a jurisprudence called the “business judgment rule”, which basically let officers and directors, for the most time, get away with whatever decision they’ve made.)

There have been mainly two interpretations of corporate governance (which I’ll discuss later), but I think both stem from the so-called “separation thesis” put out by corporate law scholar Adolf Berle and economist Gardiner Means in their book <Modern Corporation and Private Property> published in 1932. Written amidst the Great Depression, the book suggests that a revolutionary trend in the history of property rights and thus capitalism happened with the emergence of corporate structure. With the vastly dispersed shareholders among population, those who legalistically “own” claims on corporations now do not actually have a control over the intricate decision-making process and strategic choices of the management, and those handful of “managers” (officers) make decisions, without “owning” anything. Thus, with this “separation” of from the traditional (neoclassical) notion of private property (ownership, with wise use, generates profit) falls apart, so does what we have understood as capitalism.

The first interpretation, mostly developed in response to Berle/Means by some neoclassical economists and “law and economics” scholars, is called “agency theory.” It postulates that the managers of corporation are “agents” of shareholders and represent their best interests. Under this theory, optimal business decisions are made in the sole interest of the absentee ownership. Markets (with the law of supply and demand and certainly with the ECMH) make optimal decisions. Then, the interest of executives are integrated into that of shareholders. Thus, the separation of ownership and control “disappears.” Now, what matters most for a public company then is to maximize profits and shareholder value, above all other goals, as Friedman expressed(“shareholder value primacy”). While this view has been the dominant one, due to the ongoing neoliberal period and all the social harms caused by it, this theory has been so vehemently criticized that it’s becoming increasingly hard for anyone to just outright regurgitate it.

The second interpretation is what Berle/Means originally expressed in their book. While there are many variations of it, I think it can be loosely called as “stakeholder theory.” Berle and Means say that these mega-corporations are indeed quasi-public entities since most of their shares are held by individuals, so they do have a public purpose. Due to the separation, executives only serve their self-interests and by doing so they might harm the society. Therefore what is needed is the ways through which the interests of “stakeholders” – workers, local residents, government, NGOs, etc – can intervene into and control corporate entities, via legal regulations and state interventions. This view has been succeeded by others. JK Galbraith talked about “techonostructure” of corporate system and how “counterveiling forces” of government and trade unions rein in. Most famously, the late Lynn Stout at Cornell Law School called the shareholder primacy theory a “myth”: she wrote, as Berle and Means wrote, how little actual power shareholders have conveyed by law over decision-making (“shareholders don’t actually own”), how the shareholder primacy view has led to adverse phenomena like low investment and mass stock buybacks, and how traditionally corporate entities had served public purpose and why they now should do too. (https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/does-focusing-on-shareholder-value-hurt-shareholder-value)

I think something is off here. It seems that both theories are working on a normative front. They seem to be not explaining how control and power are exerted within and via corporations but how they should be done. Of course a big part of legal study is investigating this normative aspect – to make the world a better place – but again, for myself both are unsatisfactory.

Most importantly, at the end of the day, whether agency theory is right or stakeholder theory is right matters in the context of the differential accumulation of capital facilitated by corporate system?

There are also some empirical problems of Berle/Means thesis. The somewhat misleading identification of “separation” had already been pointed out by Zeitlin(1974), who called it a “pseudofact.” But most importantly, what Berle and Means “failed to consider” in their book is the rise of pension funds and mutual funds that have a meaningful share of votes that can affect decision-making. Furthermore, in the recent decade after the GFC, the accelerating concentration of ownership of assets by big institutional investors, notably “Big Three” ones including BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard, happened, and now its both theoretically and practically possible for these institutional investors and other activist groups to intervene into the decision-making process.

In fact, in this interesting paper Stephen F. Diamond at Santa Clara School of Law points out that the separation hypothesis and both agency and stakeholder theory are either wrong or irrelevant in the context of the accumulation of capital. In his words, while the power is now shared by large institutional investors, the board of directors, and senior shareholding managers, regardless, ” hold the complete bundle of rights needed to carry out the purpose of the corporation: sustaining the valorization and capital accumulation process. And it

is their shared commitment to that process, reinforced by their financial claims and legal rights, that holds them together as a socio -economic milieu or class.”https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3742395

(Yet the author bases his argument on the purely Marxist concept of capital – the bifurcation between “industrial” capital and “finance” capital – which I think CasP finds quite problematic.)

So, my questions are:

1) From the viewpoint of CasP, does the issue of corporate governance – whether a company should serve only shareholders or serve stakeholders too – matter, in the context of the accumulation of capital and concentration of power?

2) There have been talks on “Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)” and now recenlty “ESG” due to more public interests in climate change. From the viewpoint of CasP, *should* corporations (or *can* they )serve the society in general? And how would CSR/ESG look like in reality?

3) How does CasP see Galbraith’s call for countervailing force or stakeholder governance to contain corporate power? Does it have at least some merit?

Thank you!

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.