- This topic has 3 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated March 19, 2021 at 10:00 pm by .

-

Topic

-

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2021. The 1-2-3 Toolbox of Mainstream Economics: Promising Everything, Delivering Nothing. Working Papers on Capital as Power (2021/03, March): 1-26.

http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/678/

Preamble

We write this essay for both lay readers and scientists, though mainstream economists are welcome to enjoy it too. Our subject is the basic toolbox of mainstream economics. The most important tools in this box are demand, supply and equilibrium. All mainstream economists – as well as many heterodox ones – use these tools, pretty much all the time. They are essential. Without them, the entire discipline collapses. But in our view, these are not scientific tools. Economists manipulate them on paper with impeccable success (at least in their own opinion). But the manipulations are entirely imaginary. Contrary to what economists tell us, demand, supply and equilibrium do not carry over to the actual world: they cannot be empirically identified; they cannot be observed, directly or indirectly; and they certainly cannot be objectively measured. And this is a problem because science without objective empirical tools is hardly science at all.

1. Introduction

Our purpose in this paper is not to criticize demand, supply and equilibrium as such, but to show that, right or wrong, these tools do not translate into actual science.

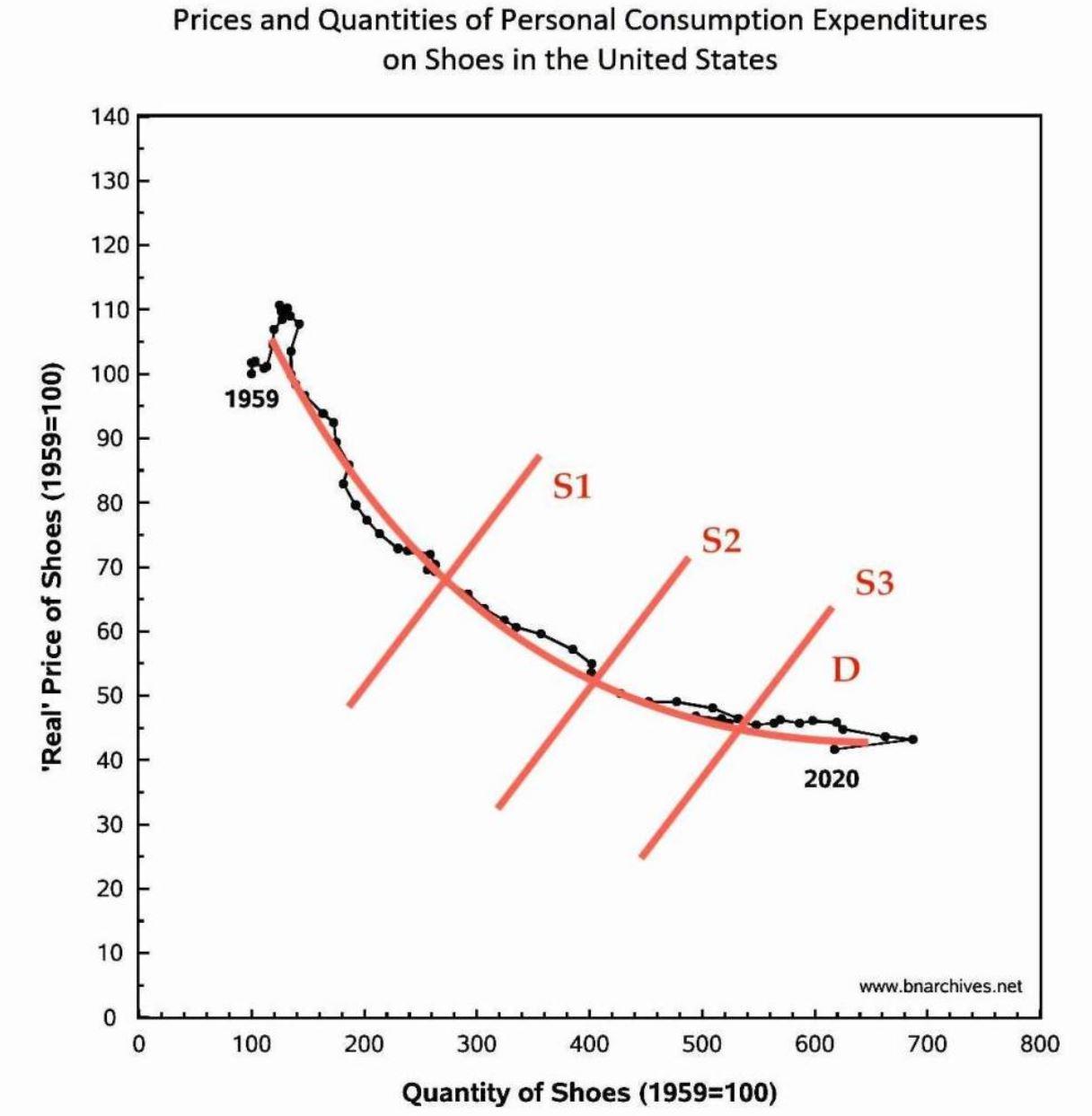

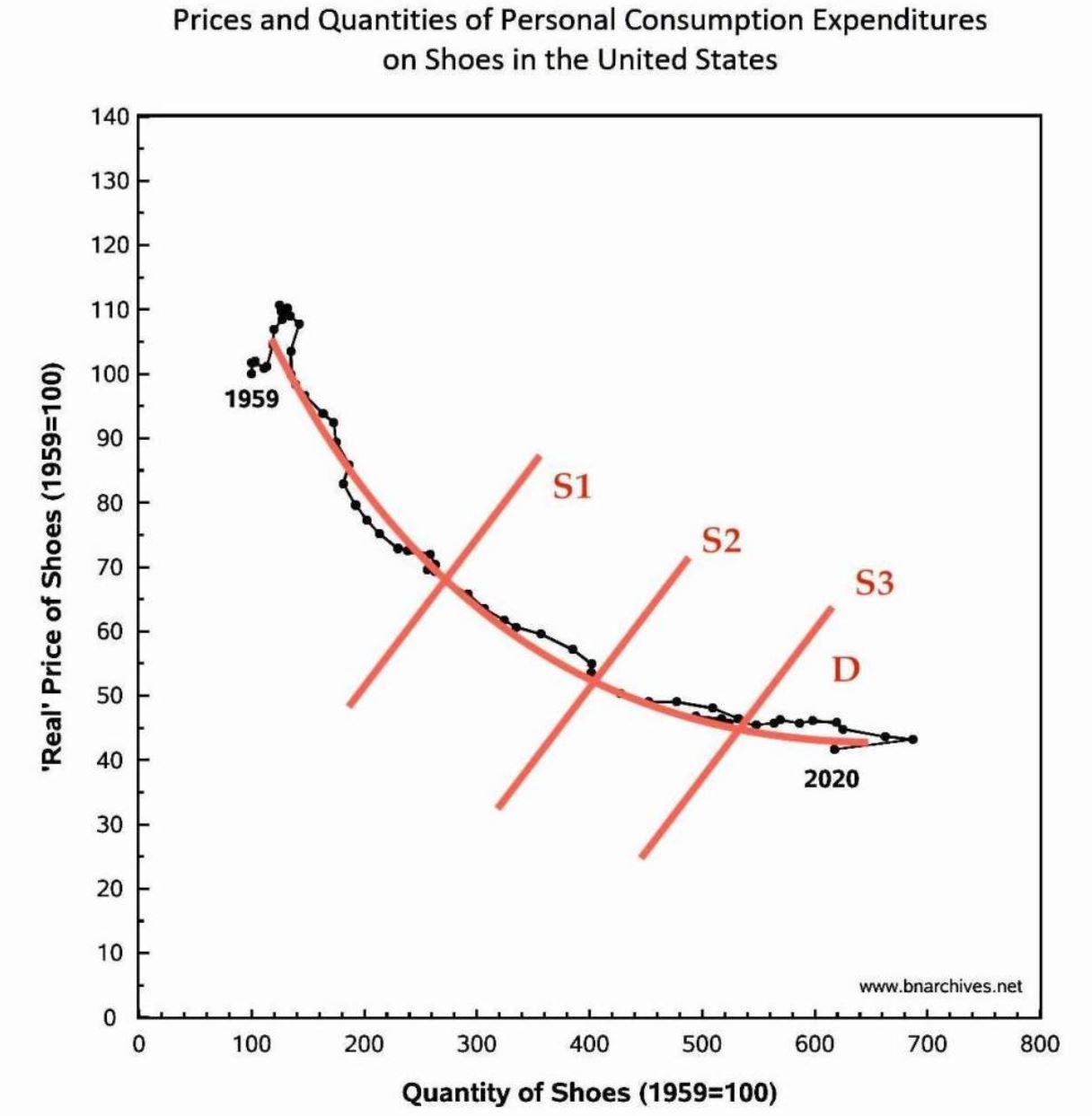

We begin in Section 2 with what we call the 1‑2‑3 toolbox of mainstream economics. Mainstream economists claim that the key tools in this box – namely, demand, supply and equilibrium – explain virtually any and every market. We argue they do not. In Section 3, we illustrate how in practice these tools produce baffling if not contradictory results and suggest they merit closer inspection. In Sections 4, 5 and 6 we offer a clean-slate outline of demand, supply and equilibrium analysis, show the price and quantity history of the U.S. shoe market, and illustrate how mainstream economists would use their 1‑2‑3 toolbox to explain it. Their explanation, though, is deeply problematic, and for the simplest of reasons: nobody, including economists, has any idea what demand, supply and equilibrium look like!

As we explain in Section 7 and 8, the demand and supply curves express the intentions of buyers and sellers, and these intentions are unknowable to outsiders (and sometimes even to those who supposedly possess them). In practice, the best economists can do is estimate demand and supply indirectly – and that does not work either. The first method, which we examine in Section 8, is to interview buyers and sellers. On the face of it, this method might seem sensible, but a deeper look shows its results are impossible to assess and often nonsensical. The second method is to estimate demand and supply curves econometrically, based on actual price and quantity data. In Section 9 we show that this method too runs into the wall. Demand and supply regressions, no matter how fancy, are tautological: they assume what they seek to prove. And that is hardly the end of it. Econometric estimates are only as good as the econometric models they are based on, and, as we show in Sections 10 to 12, these models – and therefore the estimates they generate – are virtually all bad (though nobody can say how bad, because the ‘true’ demand and supply curves, assuming they exist, are unknowable).

So, all in all, the 1‑2‑3 toolbox, even if perfectly effective on paper, is virtually useless in practice. It spews out tons of estimated coefficients, but these estimates have no demonstrable relation to the demand, supply and equilibrium they presumably represent. For all we know, these estimates are no more than ghosts in the minds of the estimators. And, as Section 13 illustrates, these ghost-like estimates often end up spread all over the place. On these counts, mainstream economics is not even close to being a science.

Continue reading: http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/678/4/20210300_bn_the_1_2_3_toolbox_wpcasp_web.htm

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.