Home › Forum › Political Economy › The concept of systemic fear

- This topic has 12 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated September 25, 2021 at 11:53 am by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

CreatorTopic

-

August 23, 2021 at 1:51 pm #245945

A small Twitter debate about systemic fear is currently brewing. It would be good to see the debate find firmer ground and give people opportunities to talk about the concept.

What is systemic fear? Is the concept useful to understand capitalist crisis? Is ‘looking backwards’ different than what some analysts do when they look at past earnings or use smoothed averages (such as the CAPE3 ratio)?

A few screenshots for context of the skeptical view:

-

CreatorTopic

-

AuthorReplies

-

-

August 29, 2021 at 8:22 pm #245988

True or false:

The systemic fear thesis (“SFT”) is based on the assertion/assumption that a rational investor/capitalist does not consider current or past information in making investment decisions.

I believe the sentence as written is “true” and the assertion/assumption is false and has been proven empirically to be so.

This why I don’t understand the value of SFT except as a way to attack the legitimacy of CasP theory. I mean, what’s the point of “differential accumulation” when all capitalists will wind up in the same place eventually, if they just let it ride and ignore facts as they develop? Never mind the fact that the stock market is cyclical, power (and, therefore) capital, is forever and infinite. Right?

Think about it: the only way you can compare yourself to the average is if you consider past information, but SFT assumes doing so is irrational even as CasP more broadly insists that it is how capitalists acquire power.

I really want somebody to explain to me what I’ve missed or overlooked about this basic aspect of SFT. I have other concerns about the methodology and data, but this issue is fundamental. Models only work (i.e., are scientific) to the extent that their assumptions and boundary conditions hold true, and my understanding of SFT’s assumptions is they are false.

Thanks in advance.

–Scot

-

August 30, 2021 at 10:23 am #245989

Thank you Scott. Here are some thoughts.

1. The CasP emphasis on forward-looking capitalization has nothing to do with investors/capitalists being ‘rational’ or ‘irrational’. In our view, forward-looking capitalization is a ritual. (Until the early 20th century, it was heatedly debated by investors and theorists, many of whom thought it was fraudulent and that asset prices should reflect backward-looking ‘real’ means of production.)

2. Forward-looking capitalization does not mean that capitalists ignore the past. It simply means that they use whatever information they have — including the past and including recent earnings — to predict future earnings all the way to infinity.

3. I think we agree that the short-term gyrations of last year’s earnings cannot tell us much about their long-term trajectory. So, if investors indeed discount expected long-term future earnings, stock prices should not be correlated with the ups and down of recent earnings.

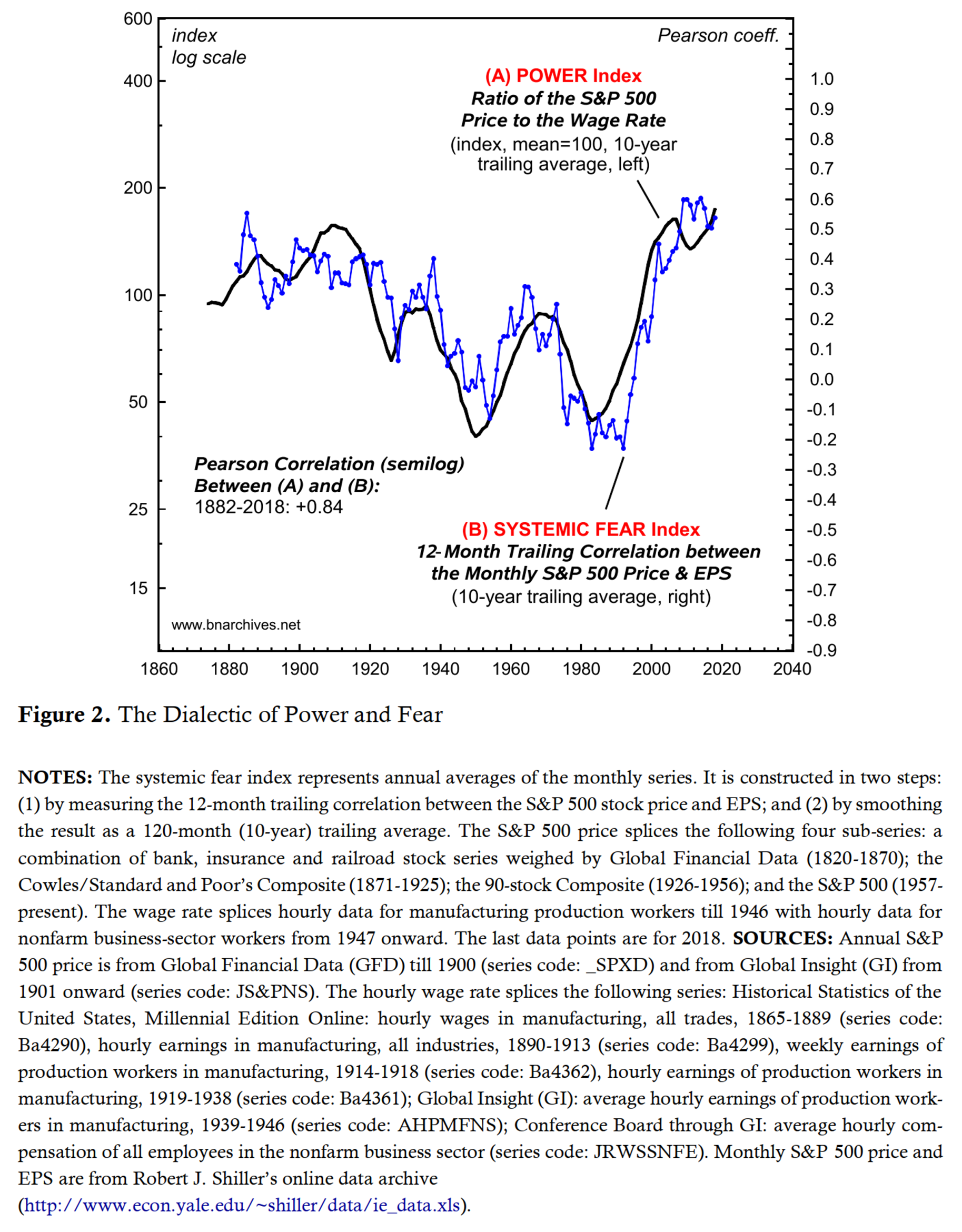

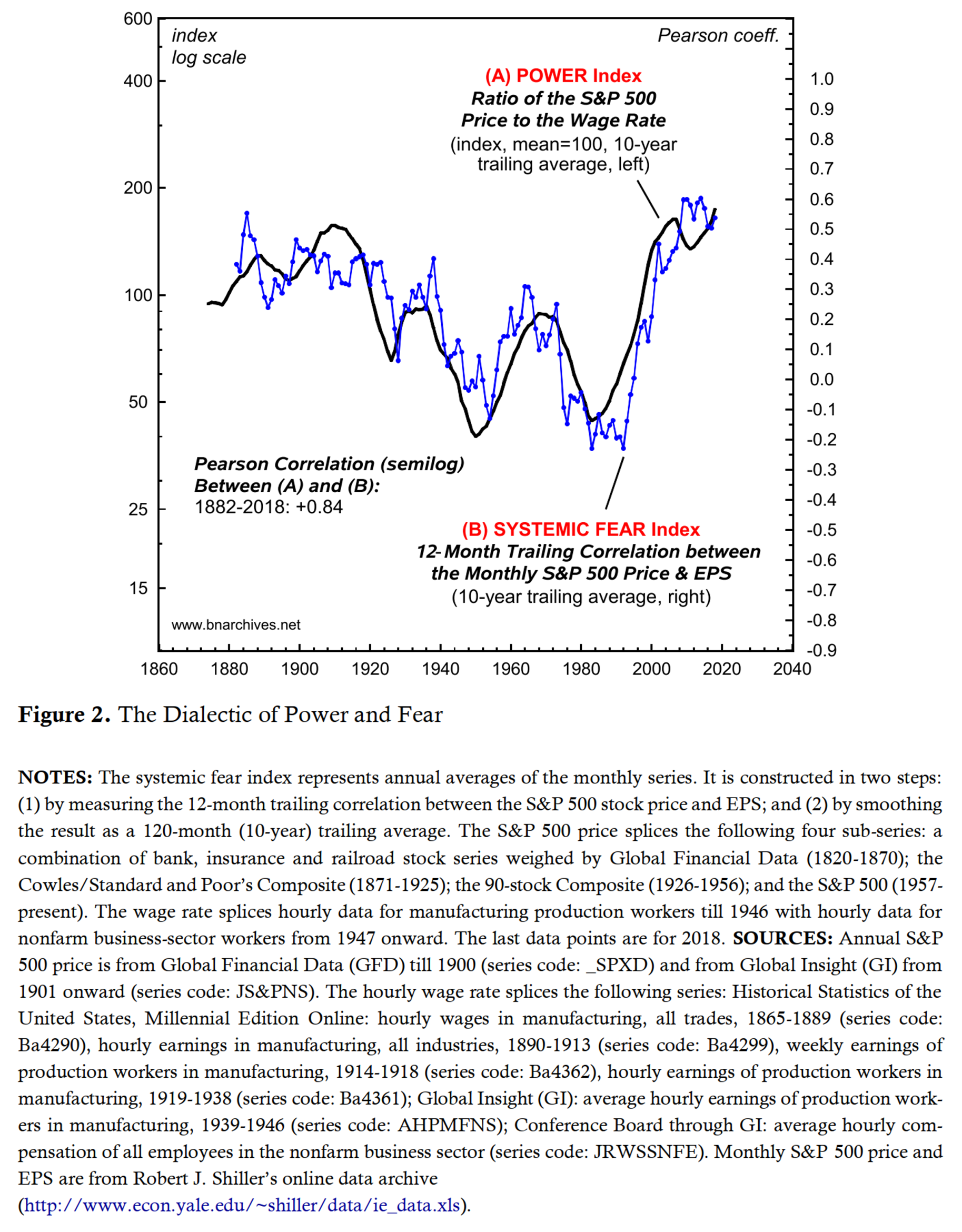

4. The data in the following chart show that, during the 1880-1980 period, as the forward-looking ritual gained traction, the correlation between price and recent earnings trended down, In the 1950s, and then in the early 1980s, it turned negative.

5. This long-term decline inverted in the early 1990s. Since then, the correlation between stock prices and recent earnings rose more or less uninterruptedly, reaching all time highs recently.

6. This inversion, we argue, represents a breakdown of the forward-looking capitalization ritual, and this breakdown is not accidental. In our opinion, it represents systemic fear – investors’ fear that the capitalization system itself might be unsustainable.

7. As the following chart shows, the entire history of the systemic fear index is associated, dialectically, with the capitalized power of capitalists, measured here by the stock price/average wage ratio: the higher this power, the greater the fear of capitalists that it cannot be sustained, and therefore their greater systemic fear.

8. The correlation in this chart suggests that the future profit expectations of forward-looking capitalists are calibrated by their power: the lesser/greater their power, the smaller/larger the significance of recent profit for their future-earning predictions.

9. This discussion deals with capitalists as a group and in that sense is unrelated to differential accumulation. Hands-on capitalists accumulate differentially by creordering the power underpinnings of their own assets in ways that affect expected differential profit, hype and risk perceptions, while absentee owners do the same by correctly predicting this creordering. The ongoing changes in overall power of capitalists calibrates the way in which their differential efforts translate into future earnings expectations: the greater/lesser this power, the greater/lesser the impact of their current actions-turned-profit on future earnings expectations.

10. And all of these differential processes — although happening here and now, and even though they are affected by the present to various degrees — are focused on the future.

-

-

August 30, 2021 at 11:43 am #245990

True or false: The systemic fear thesis (“SFT”) is based on the assertion/assumption that a rational investor/capitalist does not consider current or past information in making investment decisions. I believe the sentence as written is “true” and the assertion/assumption is false and has been proven empirically to be so.

My concern is that the sentence, as written, is setting up an impossible situation, where any looking backwards in a period of low systemic fear cancels the thesis.

As I see it, systemic fear is a symptom of being able to see a future for differential accumulation. Benchmarking, rolling-averages, reading the Financial Times, teaching important ratios like CAPE3–the past is repeatedly incorporated into investor behavior. The systemic breakdown is when there is little to do with all of this information, other than pin price to past earnings (a rising correlation of P ~ E). A 1980s capitalist can use all sorts of methods to discount future expectations–this is not the direct issue–but they have the confidence to throw future expectations farther from the past.

-

August 30, 2021 at 4:22 pm #245992

True or false: The systemic fear thesis (“SFT”) is based on the assertion/assumption that a rational investor/capitalist does not consider current or past information in making investment decisions. I believe the sentence as written is “true” and the assertion/assumption is false and has been proven empirically to be so.

My concern is that the sentence, as written, is setting up an impossible situation, where any looking backwards in a period of low systemic fear cancels the thesis. As I see it, systemic fear is a symptom of being able to see a future for differential accumulation. Benchmarking, rolling-averages, reading the Financial Times, teaching important ratios like CAPE3–the past is repeatedly incorporated into investor behavior. The systemic breakdown is when there is little to do with all of this information, other than pin price to past earnings (a rising correlation of P ~ E). A 1980s capitalist can use all sorts of methods to discount future expectations–this is not the direct issue–but they have the confidence to throw future expectations farther from the past.

Item no. 2 of Jonathan’s reply adequately refutes the sentence, thankfully.

Now I need to formulate my next set of questions (or straw man assertions), which relates to correlation and causation (and maybe a little history, as well). I am not a statistician, so I am not in a position to argue whether or not the data show correlation. I accept that they do. I am, however, in a position to question what that means statistically and what that might mean in terms of political economy.

For example, I believe as an historical matter that the ritualization of capitalization did not really begin taking root until the 1970s, after Fama’s efficient market hypothesis, the introduction of CAPM and Miller and Modigliani’s seminal papers on market capitalization. With the advent of cheap computing power in the 1980s, financial modeling became easily accessible and widely disseminated, which may explain the rapid rise of “systemic fear” starting in the 90s. Technology has empowered capitalists to be more vigilant and engaged with their investments than ever before.

As long as there are other explanations for the phenomenon called “systemic fear,” I have a hard time accepting the label. Now, if there were independent evidence that the rulers should fear the ruled, I would feel differently. But here in the US, everybody is distracted by capitalist-created “culture wars,” and everybody seems to believe there is a market-based solution for everything, even when the market is obviously the problem (e.g., housing, healthcare, education). If I’d read the original systemic fear paper back when the Occupy movement was gaining traction, I might have felt differently, as well. Nowadays, even aggressively progressive people like Elizabeth Warren self-identify as capitalists and only offer solutions to make life more bearable for the ruled, not to fundamentally change the system.

-

August 30, 2021 at 8:08 pm #245996

Thank you Scott. Here are some thoughts. 1. The CasP emphasis on forward-looking capitalization has nothing to do with investors/capitalists being ‘rational’ or ‘irrational’. In our view, forward-looking capitalization is a ritual. (Until the early 20th century, it was heatedly debated by investors and theorists, many of whom thought it was fraudulent and that asset prices should reflect backward-looking ‘real’ means of production.) 2. Forward-looking capitalization does not mean that capitalists ignore the past. It simply means that they use whatever information they have — including the past and including recent earnings — to predict future earnings all the way to infinity. 3. I think we agree that the short-term gyrations of last year’s earnings cannot tell us much about their long-term trajectory. So, if investors indeed discount expected long-term future earnings, stock prices should not be correlated with the ups and down of recent earnings. 4. The data in the following chart show that, during the 1880-1980 period, as the forward-looking ritual gained traction, the correlation between price and recent earnings trended down, In the 1950s, and then in the early 1980s, it turned negative.

5. This long-term decline inverted in the early 1990s. Since then, the correlation between stock prices and recent earnings rose more or less uninterruptedly, reaching all time highs recently. 6. This inversion, we argue, represents a breakdown of the forward-looking capitalization ritual, and this breakdown is not accidental. In our opinion, it represents systemic fear – investors’ fear that the capitalization system itself might be unsustainable. 7. As the following chart shows, the entire history of the systemic fear index is associated, dialectically, with the capitalized power of capitalists, measured here by the stock price/average wage ratio: the higher this power, the greater the fear of capitalists that it cannot be sustained, and therefore their greater systemic fear.

8. The correlation in this chart suggests that the future profit expectations of forward-looking capitalists are calibrated by their power: the lesser/greater their power, the smaller/larger the significance of recent profit for their future-earning predictions. 9. This discussion deals with capitalists as a group and in that sense is unrelated to differential accumulation. Hands-on capitalists accumulate differentially by creordering the power underpinnings of their own assets in ways that affect expected differential profit, hype and risk perceptions, while absentee owners do the same by correctly predicting this creordering. The ongoing changes in overall power of capitalists calibrates the way in which their differential efforts translate into future earnings expectations: the greater/lesser this power, the greater/lesser the impact of their current actions-turned-profit on future earnings expectations. 10. And all of these differential processes — although happening here and now, and even though they are affected by the present to various degrees — are focused on the future.

8. The correlation in this chart suggests that the future profit expectations of forward-looking capitalists are calibrated by their power: the lesser/greater their power, the smaller/larger the significance of recent profit for their future-earning predictions. 9. This discussion deals with capitalists as a group and in that sense is unrelated to differential accumulation. Hands-on capitalists accumulate differentially by creordering the power underpinnings of their own assets in ways that affect expected differential profit, hype and risk perceptions, while absentee owners do the same by correctly predicting this creordering. The ongoing changes in overall power of capitalists calibrates the way in which their differential efforts translate into future earnings expectations: the greater/lesser this power, the greater/lesser the impact of their current actions-turned-profit on future earnings expectations. 10. And all of these differential processes — although happening here and now, and even though they are affected by the present to various degrees — are focused on the future.Thank you. Attempting to reply to each point in turn:

1. I agree that what CasP calls “capitalization” and a ritual has become increasingly important to capitalism over the last 50 years, but I believe the original “ritual” was the compounding of interest on credit/loans. Capitalization is basically the inverse of compounding interest. To fully understand capital as power, I think it is important to consider capitalization and compounding together.

2. Thanks. Your clarification was very helpful. I think we are on the same page.

3. Correlation is something I should understand better, especially as it relates to this specific data. My current understanding is that positive, non-zero correlation between two variables indicates some kind of dependency (inter-dependency?) between the two, and the effects of correlation are largely directional (moving up or down together) not necessarily in terms of absolute magnitude.

4. I have some concerns about the SP500 data that I might not have if I were more immersed in statistical analysis. First, the SP500 didn’t have 500 stocks until 1957. Second, the index is curated, removing and adding stocks, as well as adjusting relative weighting, over the years in part, it appears, to maintain its upward trajectory. Third, the index price and EPS data are derived considering using a different number of shares, where index price is sums the weight-adjusted shares of the outstanding float of each company, and EPS is a straight summation of the EPS of all shares of all constituents without weighting. Does weighting a smaller number of shares for one variable but not the other leave something that doesn’t cancel out, thus creating the appearance of correlation?

Regardless of correlation, aren’t there potential causes other than “systemic fear”? For example, what about high frequency trading (HFT) and dark pools, which prevent price discovery and increasingly dominate the number of shares traded each day? What about good old fashioned concerns/fears about the business cycle: the longer a boom continues, the more behavior changes as the perceived risk of a correction grows? And where is there independent evidence that capitalists should fear the ruled?

5. What happened in the bond markets in the 80s and 90s? It looks like the long-term decline of correlation reversed when bond yields began to decline and people piled out of the bond markets into the stock market, which historically have been inversely correlated, right? Considering the stock and bond markets together might help complete the picture.

6-8. Leaving the “fear” label aside for the moment, the ascendance of the stock market and the steady decline of the bond yields since the 1980s should be cause for worry as it implies credit creation may no longer be a useful tool in differential accumulation (at most it helps you tread water). Before, the capitalist had it easy: just pile into stocks when yields fell, and pile into bonds when stock prices fell. Now they only have one lever to work with, and they work it all the time, nervously.

One question: shouldn’t the Power Index and the Systemic Fear Index be correlated when each is Index Price divided by a different variable, i.e., wouldn’t one expect P/x to be positively correlated to P/y, particularly when P is much larger than x and y, even if earnings (x) and wages (y) are likely to be somewhate inversely correlated?

-

August 31, 2021 at 9:56 am #246000

A brief follow-up to some of your specific points, Scot:

1. Compounding interest is backward-looking (it adds the interest that wasn’t paid to the balance), so in that sense, it is ‘opposite’ to forward-looking capitalization. I look forward to insight from considering them jointly.

4. Stock index data are often adjusted and spliced. I doubt that in the case of the S&P series adjustment/splicing alters the overall trajectory. As far as I know, EPS and price indices are based on the same stock weightings.

5. I look forward to bond-stock analysis that explains the changing correlation of stock price and recent earnings.

6-8. I don’t understand your ‘one question’. Our power index is the stock price/wage ratio. Our systemic-fear index is a correlation between stock price and recent earnings. I cannot see any technical reason for these totally different indices to correlate.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 10 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 10 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

August 31, 2021 at 4:36 pm #246004

A brief follow-up to some of your specific points, Scot: 1. Compounding interest is backward-looking (it adds the interest that wasn’t paid to the balance), so in that sense, it is ‘opposite’ to forward-looking capitalization. I look forward to insight from considering them jointly. 4. Stock index data are often adjusted and spliced. I doubt that in the case of the S&P series adjustment/splicing alters the overall trajectory. As far as I know, EPS and price indices are based on the same stock weightings. 5. I look forward to bond-stock analysis that explains the changing correlation of stock price and recent earnings. 6-8. I don’t understand your ‘one question’. Our power index is the stock price/wage ratio. Our systemic-fear index is a correlation between stock price and recent earnings. I cannot see any technical reason for these totally different indices to correlate.

1. I would argue that lending (or, more correctly, extending credit) at interest, whether the interest is simple or compounding, is always forward looking because the simple act of doing so creates future revenue stream (i.e., the interest), the timing and amounts of which are certain and subject only to the risk of non-payment (no need for “hype,” etc.). Capitalization as a process attempts to simulate the simplicity of lending at interest in the presence of uncertainty as to timing and amounts of returns. The “discount rate” used in capitalization as part of a capital budgeting decision-making process is set to the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) of the company to determine whether the company makes any money when the costs of borrowing to fund the project are considered. For these reasons, I view capitalization as something that was originally developed as a way for comparing investments in stocks with investments in debt (whether lending directly or purchasing bonds). (I think your 2009 book refers to using discounting methods to determine whether the early payment of debt would actually provide a discount to the debtor.)

4. Here is a link to a blog post referring to how S&P calculated the Index price and the EPS in 2009. EPS was not weighted then, and I have no reason to believe anything has changed since then, and I have downloaded the latest mathematics methodology documents from S&P.

Here is a link to the referenced WSJ article: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB123552586347065675

I don’t have full access to the article, but here are a couple of paragraphs:

A simple example can illustrate S&P’s error. Suppose on a given day the only price changes in the S&P 500 are that the largest stock, Exxon-Mobil, rose 10% in price and the smallest stock, Jones Apparel Group, fell 10%. Would S&P report that the S&P 500 was unchanged that day? Of course not. Exxon-Mobil has a market weight of over 5% in the S&P 500, while the weight of Jones Apparel is less than.04%, so that the return on Exxon-Mobil is weighted 1,381 times the return on Jones Apparel. In fact, a 10% rise in Exxon-Mobil’s price would boost the S&P 500by 4.64 index points, while the same fall in Jones Apparel would have no impact since the change is far less than the one-hundredth of one point to which the index is routinely rounded.

Yet when S&P calculates earnings, these market weights are ignored. If, for example, Exxon-Mobil earned $10 billion while Jones Apparel lost $10 billion, S&P would simply add these earnings together to compute the aggregate earnings of its index, ignoring the vast discrepancy in the relative weights on these firms. Although the average investor holds 1,381 times as much stock in Exxon-Mobil as in Jones Apparel, S&P would say that that portfolio has no earnings and hence an”infinite” P/E ratio. These incorrect calculations are producing an extraordinarily low reported level of earnings, high P/E ratios, and the reported fourth-quarter “loss.”

5. I think it is important to consider the entirety of the landscape of capital assets that make up investors’ portfolios. If you consider the dynamics and interactions between debt and equity markets, it is not difficult to imagine an alterative narrative and label for the “systemic fear index.” Rather than reflecting increasing fear of disobedience of the ruled, it may indicate increasing certainty of their power to command the obedience of the managers/executives. As a way to maintain discipline and ensure management deliver on forecasts, exercising ruthless control over management’s fortunes (which are tied up in stock options and grants) is a great way to do it.

The narrative in the US begins with the destruction of US manufacturing (and its unions) in the late 1970s and early 1980s followed by the easing of consumer credit standards to increase purchasing power even as wages remained stagnant. Extracting interest from the ruled allowed Finance to drive down yields of corporate bonds and commercial lending, which act as a drag on earnings and lead to cost-push inflation. This left the stock market as the only place to seek high yields and increased capital accumulation, which is not a bad thing because the stock market, unlike the credit markets, allows for the creation of new capital without (necessarily) increasing the money supply. Since the stock market is the only game in town, Finance rigs the game to ensure differential accumulation relative to the real rate of inflation.

6-8. I apologize for mischaracterizing the systemic fear index. That was an error on my part.

-

August 31, 2021 at 7:26 pm #246008

4. I think the WSJ critique here is misguided.

The writer contrasts two examples – one relative, the other absolute: (1) an equal 10% increase/decrease in the stock prices of a very big and a very small company; and (2) an equal $10bn increase/decrease in the earnings of these same companies.

In my view, this is a comparison of apples and oranges. Because the very large company has a greater number and/or a more expensive stock price than the very small company, a 10% increase in the price of this very large company has a much lager absolute effect than a 10% increase in the price of a very small company. Market-cap basing helps reflect these absolute differences.

This market-cap basing isn’t necessary with EPS, since this measure is already computed in absolute terms (dividing the $ sum of all earnings by the number of all outstanding shares). This is why a $10bn gain/loss of the two companies should be treated equally.

Had the WSJ writer complained that S&P weighted equal % changes in prices but didn’t weight equal % change in earnings, then the criticism would have been valid. But as stated, I think it is invalid.

5. I look forward to an empirical analysis of both stocks and bonds that explains the changing correlation of stock price and recent earnings, and why changes in the correlation correlate so tightly with the stock price/wage ratio.

-

-

August 31, 2021 at 8:20 pm #246011

4. I think the WSJ critique here is misguided. The writer contrasts two examples – one relative, the other absolute: (1) an equal 10% increase/decrease in the stock prices of a very big and a very small company; and (2) an equal $10bn increase/decrease in the earnings of these same companies. In my view, this is a comparison of apples and oranges. Because the very large company has a greater number and/or a more expensive stock price than the very small company, a 10% increase in the price of this very large company has a much lager absolute effect than a 10% increase in the price of a very small company. Market-cap basing helps reflect these absolute differences. This market-cap basing isn’t necessary with EPS, since this measure is already computed in absolute terms (dividing the $ sum of all earnings by the number of all outstanding shares). This is why a $10bn gain/loss of the two companies should be treated equally. Had the WSJ writer complained that S&P weighted equal % changes in prices but didn’t weight equal % change in earnings, then the criticism would have been valid. But as stated, I think it is invalid. 5. I look forward to an empirical analysis of both stocks and bonds that explains the changing correlation of stock price and recent earnings, and why changes in the correlation correlate so tightly with the stock price/wage ratio.

4. I just wanted to bring this to your attention just in case it mattered. Again, I am not a statistician, but I was concerned there might be something in how the S&P was doing things that might create a dependency somehow. If you are good with their approach, then I am fine, too.

5. I look forward to somebody doing that, as well. The fact remains that a lot of things in finance started changing around the same time. To me, they indicate aggressive creording, as you say. Capitalists no longer fear the ruled because the ruled think they’re capitalists, too, and they’ve been conditioned to blame their government for their failures, not capitalists. If you accept the phenomenon you’ve discovered as true, regardless of how you label it or what you believe motivates it, it seems to indicate a fundamental change to the capitalist creorder, and if the correlation is increasing with time, maybe that indicates we’re still in transition towards a new steady-state.

In closing, one of the necessary constituent elements of capitalism is fraud. Without fraud, in particular the “normative myths” such as the duality of politics and economics, capitalism would never have been successful. Capitalists indicate in everything they do that they know that the stock market is subject to risk and uncertainty, i.e., they know they can’t just let everything ride and hope for the best, but as long as they can control that to ensure differential accumulation, they don’t mind making less in the near term to ensure steady growth in the long term. What you call “systemic fear” may just be another manifestation of differential accumulation.

-

August 31, 2021 at 8:45 pm #246012

Capitalists no longer fear the ruled because the ruled think they’re capitalists, too, and they’ve been conditioned to blame their government for their failures, not capitalists

Yes, fraud is a very potent weapon, particularly in capitalism. But we should be careful of appearances. The overt power of the rulers always hides covert fear of losing this power, and collapse, from Belshazzar in Babylon to the communist parties in Euroasia, often occurs when the rulers are caught in their hubris.

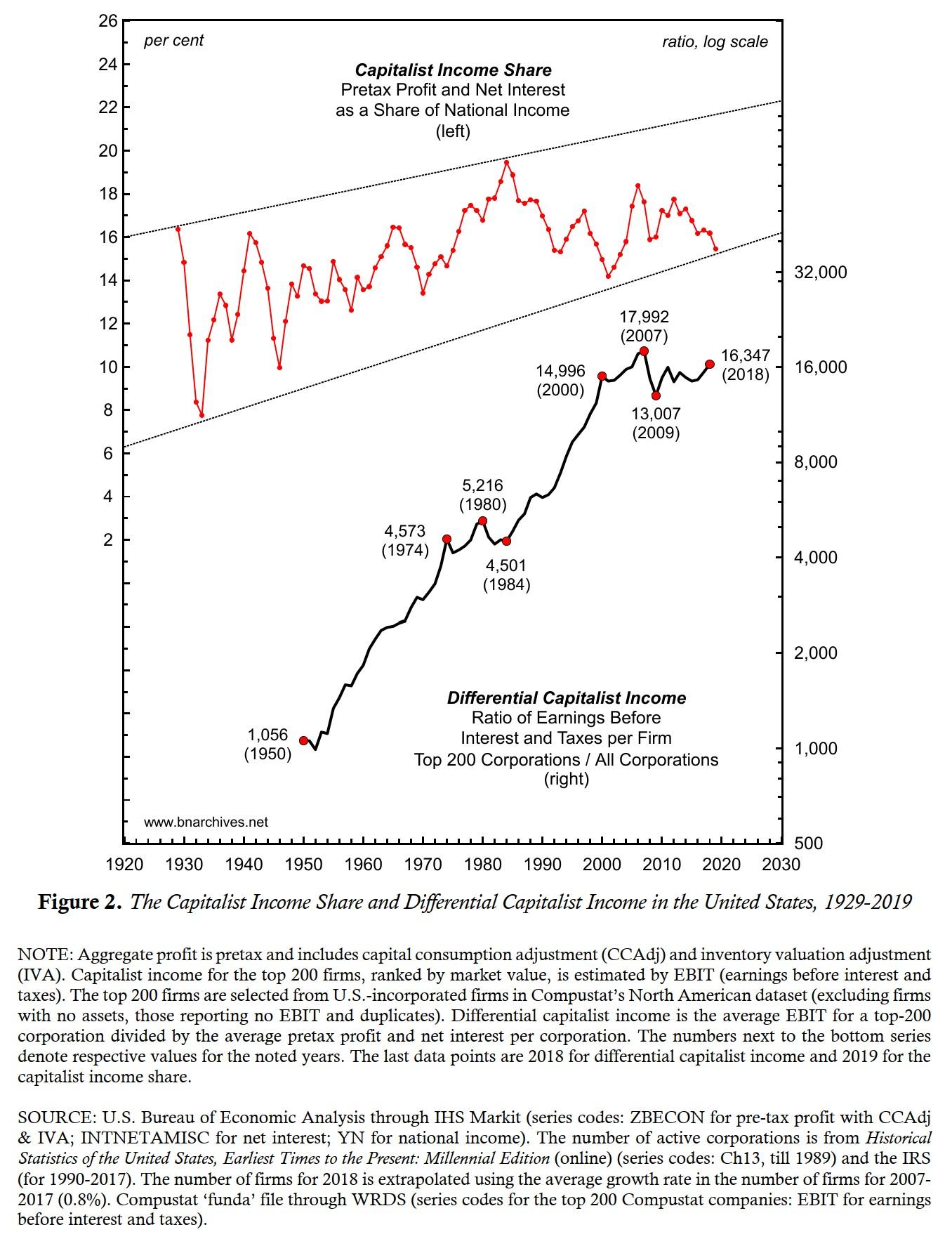

This chart, taken from ‘The Limits of Capitalized Power. A 2020 U.S. Update‘, shows that the power of U.S. capitalists in general and dominant capital in particular, having increased dramatically in the last century, is now running against an asymptote.

I’m not sure this asymptote is entirely lost on those in power.

-

-

September 24, 2021 at 6:20 pm #246807

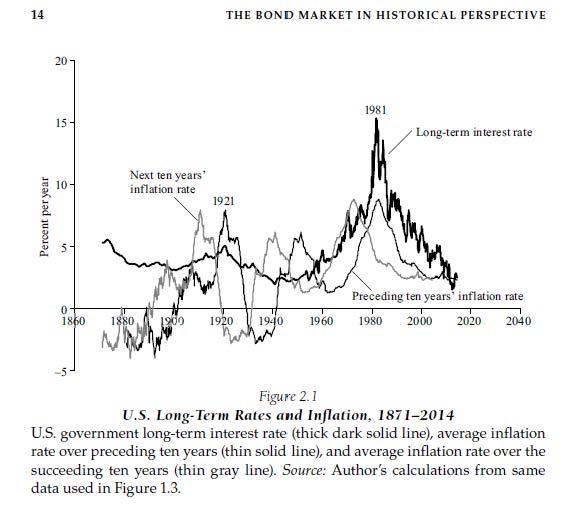

From 1960 until 2000, 10-year US treasury yields appear to have correlated with the average inflation rate of the previous ten years.

How does this relate to the Power Index and/or systemic fear, if at all?

Or is this just what creordering looks like?

From Chapter 2 of Schiller’s Irrational Exuberance:

-

September 25, 2021 at 11:53 am #246836

From 1960 until 2000, 10-year US treasury yields appear to have correlated with the average inflation rate of the previous ten years. How does this relate to the Power Index and/or systemic fear, if at all? Or is this just what creordering looks like?

- Power Index = (future profit * hype)/(normal rate of return * risk)/wage rate

- Systemic Fear Index =12-month correlation (current price, current EPS).

With respect to the Power Index, current inflation can affect three current variables: hype (up or down), the normal rate of return (mostly up) and the wage rate (almost always up). It should have no impact on future profit and risk, which are forward-looking variables. All in all, the overall direction of its effect on the Power Index is difficult to theorize.

With respect to the Fear Index, current inflation can affect price and EPS, which are both current, though the impacts are unclear. The overall effect on the price-EPS correlation is therefore hard to guess.

Schiller’s correlation between treasury yields and inflation 10 years earlier adds another layer to these already opaque relationships.

Maybe this is one of Mr. Schiller’s irrationalities?

- This reply was modified 3 years, 9 months ago by Jonathan Nitzan.

-

-

-

AuthorReplies

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.