- This topic has 4 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated June 10, 2021 at 9:08 pm by .

-

Topic

-

1. Many mainstream economists, including the illustrious Larry Summers, have been warning of inflation, not just as the global economy ‘heats up’ due to post-covid re-opening, but also because all that government stimulus has inflated the pocketbooks of workers.[1] Others, like Mark Blyth, argue that we will see “bottlenecks,” like those in shipping containers, chips, lumber, copper, etc. but that those are “just basically short-term factors that will dissipate after 18 months” In Blyth’s view, labor power is not nearly strong enough to raise its own wages to the point at which high general inflation would occur.[2]

My first question to the forum is with regard to “bottlenecks.” Is this what is really happening? It’s clear that, while lots of businesses suffered from falling demand during the pandemic, others thrived, or at least, were relatively unaffected: online retail and housing construction being two of the most prominent. Does this explain the ‘shortages’ that have supposedly led to surging prices?

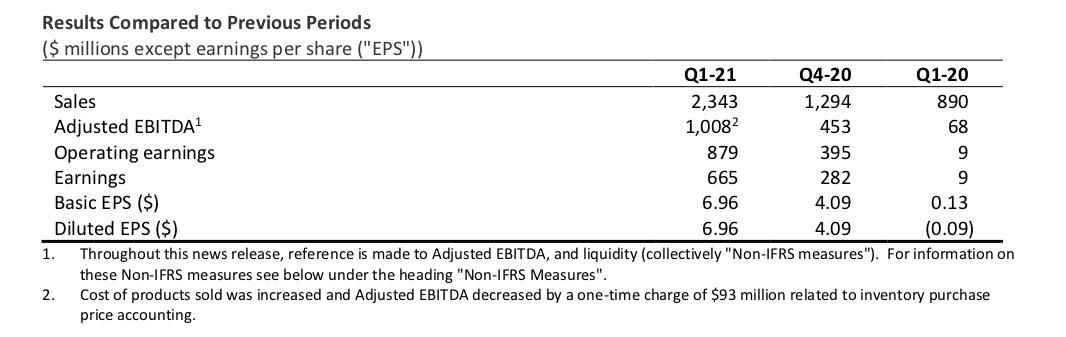

Take the case of West Fraser Timber Co. In February of this year, West Fraser, one of the world’s leading wood product manufacturers, completed the acquisition of Norbord, another of the world’s leading manufacturers of wood products.[3] Here is West Fraser’s Q1 2021 earnings report, which compares earnings to previous periods:[4]

While sales increased by 260%, between Q1-20 and Q1-21, earnings increased 7400%. The company’s markup (earnings/sales) went from 1% to 28% (please check my math on these numbers!).

This company is also a manufacturer of lumber, meaning that for it, higher lumber prices mean increased costs. It seems to me that while “surging” demand might plausibly explain some of that increase, the concentration of power in certain areas of production is also a central factor in price increases. However, there is high concentration is many industries, so concentration in general does seem a satisfactory explanation either. Any thoughts on why these particular industries are seeing extreme price increases besides ‘surging demand’? Is it simply a combination of demand, concentration and opportunism, and are there other factors to consider?

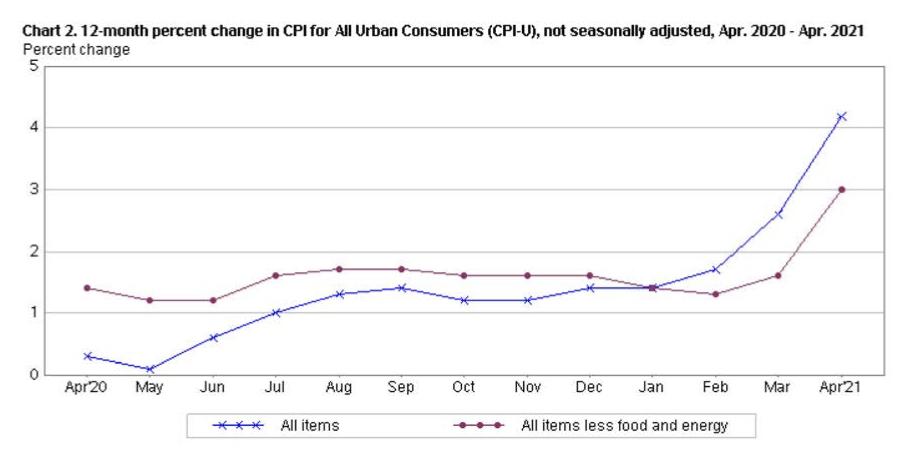

2. In addition, it seems there are some signs that more general price increases are occurring:[5]

With regard to the more general situation of rising prices, Thorstein Veblen has an interesting point about gold rushes, which he later relates to the expansion of credit more generally:

“Any inflation of money-values due to an increased supply of specie will enhance the corporation’s assets, while it leaves the outstanding obligations at the old figure. Inflation, therefore, signifies net gain to the corporation in all its book-values; and its assets will serve as collateral to float that much more debt, with a fixed charge.

In the last analysis, of course…the traffic must be made to bear such charges in perpetuity as will yield that rate of net gains which is called for by this expanded recapitalization. And the staple procedure dictated by sound business principles in such a case is to increase the schedule of charges and curtail the output.”[6]

It seems to me that, contrary to the mainstream opinion that ‘bubbles always deflate’, the inflation of credit during the pandemic, perhaps particularly through stock prices (as well as other assets) has ‘created’ (not sure of that’s the right word) the need to raise prices and curtail output in order to achieve the inflated expectations of future profit. In other words, in the short term, all things being equal, inflation of asset prices might lead to a commensurate, if differential, increase in inflation. What is interesting however, is that by far the biggest stock market winners are not really directly implicated in the industries currently undergoing price surges (as far I know). So there are some missing pieces to my application of Veblen’s analysis. Any thoughts on a potential relation between asset inflation and prices?

My final question is regarding the current general state of affairs. Nitzan and Bichler have argued persuasively that stagflationary periods during the twentieth century appear to occur most intensely when certain ‘envelopes’, or structural obstacles to the differential accumulation of power by dominant capital groups, occur.[7] It does not seem to me that the pandemic itself presented much of an obstacle (rather, it seems like it has been an opportunity). On the other hand, as Nitzan and Bichler have recently argued, prior to the pandemic (at least in the US), dominant capital was encountering increasing difficulties increasing its share of society’s wealth.[8]

So: Do you think the pandemic accelerated the end of a long global breadth regime? Are larger structural factors at work? No need for Blythian predictions! I’m just curious if there are facets of what is going on that I haven’t considered.

Sources:

[2] https://theanalysis.news/interviews/mark-blyth-the-inflated-fear-of-inflation/

[3] https://marioncoherald.com/2021/02/18/west-fraser-completes-acquisition-of-norbord/

[4] https://www.westfraser.com/sites/default/files/First%20Quarter%20Results%20-%20May%206%2C%202021.pdf

[6] Veblen, Thorstein. Absentee Ownership: Business Enterprise in Recent Times: The Case of America. Transaction Publishers, 2009: pp 183-184.

[7] Nitzan, Jonathan and Bichler, Shimshon. Capital as Power: A Study of Order and Creorder. RIPE Series in Global Political Economy. New York and London: Routledge, 2009.

[8] http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/336/2/20120600_bn_the_asymptotes_of_power_rwer.pdf

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.