Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

I just finished Katharina Pistor’s book The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality.

I enjoyed it, although it’s not without shortcomings. I particularly like her telling of how the law has evolved to ensconce the power of owners (my words, not hers). Most interesting (to me) is the evolutionary nature of this process. Old ideas (like the trust) get re-used, altered, and nested to create the complex legal web of ownership use by today’s ruling class. And of course, there’s the role of lawyers as the Consigliori of capitalists …

In effect, Pistor is describing what Nitzan and Bichler call the nomos of capitalism … the belief structure in which it operates and perpetuates. Nitzan and Bichler deal with this structure at a very high level. Pistor gets into the nitty gritty, which I enjoyed.

What annoyed me? Well, there are aspects of the book that are decidedly mainstream. And predictably, there’s no engagement with CasP (although one Nitzan-Bichler paper gets a mention in a footnote). But I would love to see CasP researchers dive more into the law, because it is undoubtedly what codifies capital, as Pistor observes.

- This reply was modified 10 months, 4 weeks ago by Blair Fix.

- This reply was modified 10 months, 4 weeks ago by Blair Fix.

Attachments:

You must be logged in to view attached files.December 18, 2023 at 9:02 am in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249898Oh, and here is Peter Turchin’s response to a 2019 essay by the Davids. He really goes after their strawman techniques and refusal to quantify.

December 18, 2023 at 8:58 am in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249897Thanks for the thoughtful comments, Chris.

Here are some fascinating books that use an evolutionary lens for studying deep human history:

Ultrasociety: How 10,000 Years of War Made Humans the Greatest Cooperators on Earth, by Peter Turchin.

Ultrasociety: How 10,000 Years of War Made Humans the Greatest Cooperators on Earth

The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution, by Richard Wrangham

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Goodness_Paradox

Not By Genes Alone: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution, by Peter J. Richerson and Robert Boyd

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/N/bo3615170.html

November 26, 2023 at 1:45 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249881Thanks Steve. You raise good points. Essentially, we’re dealing with an absence of evidence. There is nothing in the deep archaeological record that suggests massive inequality.

Scientists usually take this to mean that inequality was absent, in the same way that the absence of evidence for little green men presumably means that little green men don’t exist. Both are assumptions … the absence of evidence never proves the non-existence of a thing.

What Dawn does is push back the dates in which there are signs of inequality. But the problem, again, is the strawman arguments. Many working scientists are aware of this evidence. So the claim that it is revolutionary is overstated. It’s like finding a fossil of an anatomically modern human that’s a bit older than expected. It hardly changes everything about our understanding of human evolution.

Another point, raised by David Boehm, Peter Turchin, and recently Richard Wrangham is that human paleolithic egalitarianism was actually a departure from our primate heritage. Wrangham makes the case that we basically domesticated ourselves — we used reverse dominance to kill off the big violent alpha males, turning ourselves into a much more socially docile species. The book is called The Goodness Paradox. I thoroughly enjoyed it, except for Wrangham’s refusal to discuss group selection. But that’s a whole other can of worms.

Back to Dawn. After a few days of reflection, here are my thoughts.

On the one hand, Dawn is a stunning piece of scholarship. The Davids compile a massive array of case studies to make the case that pre-history was extremely messy. Societies went in all sort of directions, some getting bigger and more hierarchical, while other societies rejected hierarchy and the trappings of agriculture. This evidence should be celebrated and taken seriously.

On the other hand, Dawn is a stunning example of bad science. It repeatedly attempts to win points by ridiculing theoretical straw men.

Sure, some anthropologists of the past once believed in a naive, linear view of evolution in which all societies went through distinct phases. Likewise, some evolutionary biologists of the past once thought of evolution in terms of the laughable ‘ascent of man’ imagery, in which all of life was working to make humans possible.

The problem is that today, few (if any) working scientists take these ideas seriously. They know that evolution is complex, contingent and messy. So it is frustrating to see the Davids take pot-shots at ideas that modern scientists don’t hold. In fact, I’d wager that very little of the evidence marshalled in Dawn would be considered controversial by working scientists.

So let’s diagnose the biggest problem with Dawn, which is this: the David’s cite many examples of individual trees; then they use these examples to make controversial claims about the forest. But the Davids don’t actually try to measure the forest to see if their inference is correct. It’s a big mistake.

Here’s an analogy by way of life’s evolution. To play the Davids’ game, I start by ridiculing the ascent-of-man imagery as hopelessly wrong. But I don’t tell you that most working scientists agree that this view of evolution is wrong.

Then I bombard you with a list of case studies which show that individual organisms evolve in all sorts of direction. Some ‘choose’ to get larger and more complex. Others ‘choose’ to get smaller and simpler. Again, I don’t tell you that this evidence is widely known and uncontroversial. At the level of individual species, evolution takes all directions at once, and working scientists know that.

Then the twist. I take this well-known evidence and claim that everything you think you know about the origin of life is wrong. In fact, it’s ridiculous to think that life even had an ‘origin’.

Here’s the problem with this reasoning. I’m taking observations about the trees and making inferences about the forest. But the catch is that I’m doing it without actually quantitatively aggregating the trees to look for average trends.

Yes, at the species level, evolution goes in all directions at once. But if we aggregate the big picture, it’s clear that life started small and then branched into bigness. Or put in more mathematical terms, life evolved a ‘fat-tail’ distribution of big organisms. The net effect is that on average, over billions of years, life got bigger. Looking at this average, it’s very clear that if you reverse the trend, it implies that life had an origin that was small. (Extensive DNA evidence corroborates this inference.)

I think the same is true for human societies. As the Davids show, there is a stupendous richness to the evolution of individual societies. But they error in then boldly arguing that this richness implies that inequality has no origin. Scientists who’ve tried to measure trends across time (i.e. measure the forest) clearly see a pattern towards societies with larger scale and more inequality. So when we look at the forest, it does appear that inequality has an origin, at least in a statistical sense.

So here’s my main beef with Dawn. The facts it musters are all consistent with what in my mind is the modern evolutionary understanding of human social evolution. In terms of the big picture, humans evolved from small-group living primates to present-day industrial societies which span the globe. There was never anything ‘inevitable’ about this process … indeed, it depended (like all evolution) on a whole series of contingent events. Still, the big picture trend towards larger scale and greater inequality is fairly clear (again, in a statistical sense).

This average trend is one set of facts, visible when we aggregate across many societies and large swaths of time. The other set of facts is of a whopping mess. When we zoom into the small picture, we find groups and societies going in all sorts of directions. Again, this mess is expected. The big-picture trends are statistical, not absolutes adhered to by every society.

Then problem with Dawn is that it insists on a strawman version of evolutionary theory, one in which large-scale statistical trends are universal laws of nature with no known violation. But few (if any) working scientists hold this view. So the book argues against an imaginary opponent.

So here’s the bottom line. Minus the ubiquitous strawman arguments, the Davids have written a welcome volume that illuminates the richness of human social evolution. So perhaps a better, less grandiose title would have been this: ‘Taking all roads at once: Social experimentation during the neolithic era’.

November 24, 2023 at 4:51 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249879The Davids begin the final chapter with the following summary:

This book began with an appeal to ask better questions. We started out by observing that to inquire after the origins of inequality necessarily means creating a myth, a fall from grace, a technological transposition of the first chapters of the Book of Genesis – which, in most contemporary versions, takes the form of a mythical narrative stripped of any prospect of redemption. In these accounts, the best we humans can hope for is some modest tinkering with our inherently squalid condition – and hopefully, dramatic action to prevent any looming, absolute disaster.

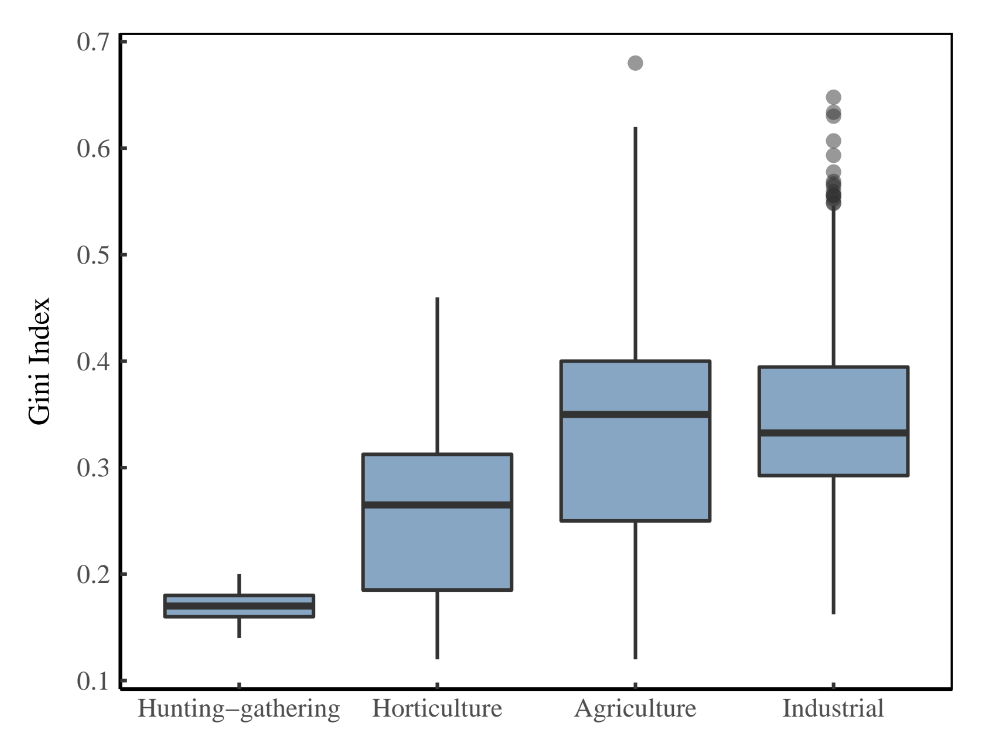

Again, I can’t help but feel that the Davids are making a strawman argument that they maintain by refusing to look systematically at quantitative evidence. When we look systematically at attempts to measure inequality, and to put these measurements into different categories of society, we get the pattern shown below.

Looking at this chart (which is from my Dissertation), I see nothing ‘inevitable’ about inequality. Instead, I see a ‘radiation’ of inequality as (some) societies began to exploit more energy. What’s essential is that some societies — whether horticultural, agriculture, or industrial — stayed quite equal. But other societies explored the depths of despotism. So what seems to have happened is that access to more energy increased the upper threshold on inequality. But it did nothing to the lower limit of inequality.

In short, we can maintain that inequality has an origin and maintain that we can do much more than ‘tinker’ with our inherently squalid conditions.

November 24, 2023 at 4:27 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249878In Chapter 11, the Davids mount a critique of ‘evolutionism’:

One problem with evolutionism is that it takes ways of life that developed in symbiotic relation with each other and reorganizes them into separate stages of human history. By the late nineteenth century, it was becoming clear that the original sequence as developed by Turgot and others – hunting, pastoralism, agriculture, then finally industrial civilization – didn’t really work. Yet at the same time, the publication of Darwin’s theories meant that evolutionism became entrenched as the only possible scientific approach to history – or at least the only one likely to be given credence in universities.

Here again, I think they’re arguing against a strawman. Sure, some early (racist) social scientists looked at social evolution as an inevitable progression towards European civilization. But does any modern social scientist subscribe to this view, especially the ones working from an evolutionary lens?

I mean, symbiosis is a basic fact that evolutionary biology tries to explain. Does it make much sense to raise symbiosis as a critique of ‘evolutionism’? And what do the David’s mean that evolutionism ‘became the only possible scientific approach to history’? For that matter, how can you study history without recognizing that cultures evolve?

Why the relentless lampooning of the silly ‘stages of evolution’ theory, and not serious engagement with modern theories of cultural evolution?

November 24, 2023 at 4:08 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249877Well, Chapter 10, “Why the State Has No Origin” has made me laugh, and in a good way. Take this quote:

For much of the twentieth century, social scientists preferred to define a state in more purely functional terms. … Basically, all it says is that, since states are complicated, any complicated social arrangement must therefore be a state.

This little joke cuts to the heart of so many problems in theories of the state. Basically, no one agrees what ‘the state’ is, so no one can agree on how it came to exist. My take is that the whole fuss is about a category that’s too fuzzy to be worth much effort. Better to focus on something more concrete, like the scale of hierarchy.

November 24, 2023 at 3:32 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249875Continuing with the theme of innumeracy, I’m struck by the David’s discussion of scale. They write:

In the standard, textbook version of human history, scale is crucial. The tiny bands of foragers in which humans were thought to have spent most of their evolutionary history could be relatively democratic and egalitarian precisely because they were small. It’s common to assume – and is often stated as self-evident fact – that our social sensibilities, even our capacity to keep track of names and faces, are largely determined by the fact that we spent 95 per cent of our evolutionary history in tiny groups of at best a few dozen individuals.

What follows is a chapter which critiques the issue of scale in social evolution. But what is striking is the almost complete absence of quantification in this critique. And when numbers enter in, they’re mostly one offs rather than any systematic investigation.

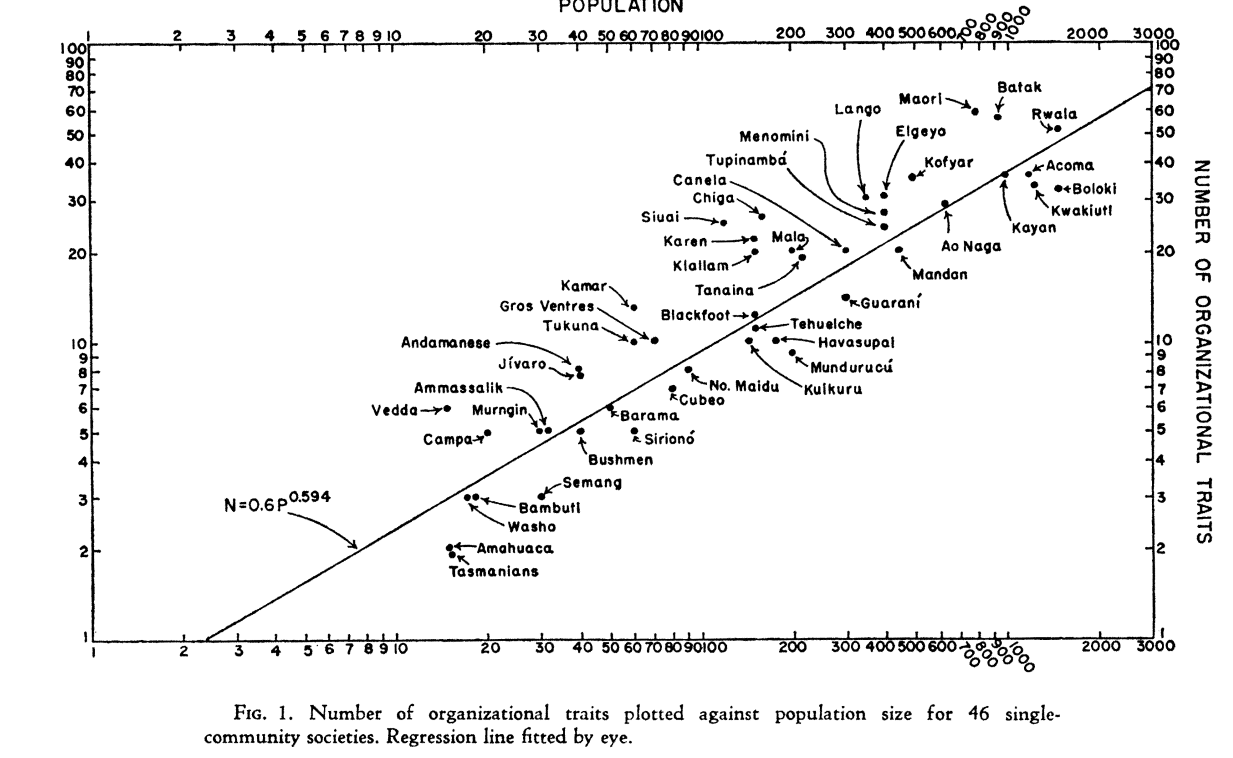

Contrast the Davids’ approach with Robert Carneiro’s paper ‘On the Relationship between Size of Population and Complexity of Social Organization’. Here’s his systematic study of the relation between population (scale) and the number of organizational traits.

If the Davids want to critique this kind of quantitative evidence, avoiding numbers isn’t the way to do it.

Attachments:

You must be logged in to view attached files.November 24, 2023 at 2:58 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249873As I read Dawn, I’m becoming increasingly annoyed by what, in my mind, amounts to innumeracy from the Davids. Start with the following very interesting description of early agriculture:

In the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East, long regarded as the cradle of the ‘Agricultural Revolution’, there was in fact no ‘switch’ from Palaeolithic forager to Neolithic farmer. The transition from living mainly on wild resources to a life based on food production took something in the order of 3,000 years. And while agriculture allowed for the possibility of more unequal concentrations of wealth, in most cases this only began to happen millennia after its inception. In the centuries between, people were effectively trying farming on for size, ‘play farming’ if you will, switching between modes of production, much as they switched their social structures back and forth.

The Davids conclude:

Clearly, it no longer makes any sense to use phrases like ‘the Agricultural Revolution’ when dealing with processes of such inordinate length and complexity.

I just cannot understand this statement. If anatomically modern humans have been around for at least 300,000 years, isn’t a 3000-year transition a blink of the eye? And why does the fact that a transition is ‘complex’ mean that we can’t call it a ‘revolution’?

- This reply was modified 1 year, 7 months ago by Blair Fix.

November 24, 2023 at 2:23 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249872More weird strawman arguments, this time about Yuval Harari. I’ll be the first to say that I don’t take Harari seriously … I suspect that few social scientists do. So it’s not really worth discussing his ‘theory’ of agriculture, since there really isn’t one.

In this case, the Davids chose to critique Harari’s rhetorical technique in which he looks at agriculture from the perspective of wheat:

Yuval Harari waxes eloquent on this point, asking us to think ‘for a moment about the Agricultural Revolution from the viewpoint of wheat’. Ten thousand years ago, he points out, wheat was just another form of wild grass, of no special significance; but within the space of a few millennia it was growing over large parts of the planet. How did it happen? The answer, according to Harari, is that wheat did it by manipulating Homo sapiens to its advantage. ‘This ape’, he writes, ‘had been living a fairly comfortable life hunting and gathering until about 10,000 years ago, but then began to invest more and more effort in cultivating wheat.’ If wheat didn’t like stones, humans had to clear them from their fields; if wheat didn’t want to share its space with other plants, people were obliged to labour under the hot sun weeding them out; if wheat craved water, people had to lug it from one place to another, and so on.

Don’t the Davids understand that Harari is basically telling a joke? His story is fun rhetoric. No one, not even Harari, takes it as a serious theory. So it’s odd that the Davids proceed to mount a serious critique of this joke.

November 24, 2023 at 1:50 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249869Some more frustrations. I’m annoyed that the David’s pay so little attention to war and violence. They put a lot of emphasis on human agency, on the fact that humans make culture the way they like. But the big hole here is the interaction between cultures.

Suppose that a hierarchical society conquers a non-hierarchical society. Sure, both societies made choices that led to their form of organization. But these choices tell us little about why hierarchy spread. The hierarchy spread because it defeated the other society.

This is the view taken by multi-level selection theorists like Peter Turchin. I find it frustrating that the David’s don’t engage with this highly relevant theory. Here’s a prime example. The Davids ask:

Was farming from the very beginning about the serious business of producing more food to supply growing populations? Most scholars assume, as a matter of course, that this had to be the principal reason for its invention. But maybe farming began as a more playful or even subversive kind of process – or perhaps even as a side effect of other concerns, such as the desire to spend longer in particular kinds of locations, where hunting and trading were the real priorities.

I don’t really understand this question. I’m sure that humans had many different reasons for taking up farming. And these reasons are interesting. But in my mind, the more important feature of farming is that it spread at the expense of other ways of being. Why did it spread? What features of farming societies led them to out-compete non farmers? The Davids don’t ask these questions.

November 24, 2023 at 1:05 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249868I’m enjoying the David’s discussion of seasonality. It seems like a fruitful avenue of research. Still, they draw weird conclusions. For example:

In other words, there is no single pattern. The only consistent phenomenon is the very fact of alteration, and the consequent awareness of different social possibilities. What all this confirms is that searching for ‘the origins of social inequality’ really is asking the wrong question.

To a quantitative scientist like me, this wordplay is bizarre. How can you say anything about variation and the lack of pattern if you don’t measure anything? We could make similar arguments about human height — it’s all about variation and there is no single pattern. But when we actually measure height across time, we find that there is a pattern — humans tended to get taller during the industrial revolution.

The David’s use of anecdotes without systematic quantification is frustrating, given the sweeping nature of their conclusions.

November 24, 2023 at 12:51 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249867Here’s another example of what, in my opinion, is a strawman argument:

It’s easy to see why the neo-evolutionists of the 1950s and 1960s might not have known quite what to do with this legacy of fieldwork observations. They were arguing for the existence of discrete stages of political organization – successively: bands, tribes, chiefdoms, states – and held that the stages of political development mapped, at least very roughly, on to similar stages of economic development: hunter-gatherers, gardeners, farmers, industrial civilization.

Did the ‘neo-evolutionists’ actually make the case for ‘discrete stages’? Or did they make the case that there are some fuzzy categories into which we can lump societies, much like there are fuzzy categories into which we can lump animals?

And even if the scientists of the 1950s thought this way, it’s now the 21st century. Do any modern social scientists insist on discrete, linear stages of social evolution? I can’t think of any. So who, exactly, are the Davids arguing against?

November 24, 2023 at 12:20 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249864I’ve been working through Dawn of Everything with interest. Here are some preliminary thoughts.

One of the things that strikes me about the book is the tone, which is overtly polemical. Usually, I enjoy a good polemic, but in this case I find the tone off putting. I’m trying to understand why.

I think it’s the particular mix of polemics and strawman arguments. To me, what makes a good polemic is the devastating, detailed deconstruction of someone’s argument. But as I’m reading Dawn of Everything, I find myself consistently noticing polemics about strawmen.

Here’s an example discussing the work of David Boehm:

So, according to Boehm, for about 200,000 years political animals all chose to live just one way; then, of course, they began to rush headlong into their chains, and ape-like dominance patterns re-emerged. The solution to the battle between ‘Hobbesian hawks and Rousseauian doves’ turns out to be: our genetic nature is Hobbesian, but our political history is pretty much exactly as described by Rousseau. The result? An odd insistence that for many tens of thousands of years, nothing happened. This is an unsettling conclusion, especially when we consider some of the actual archaeological evidence for the existence of ‘Palaeolithic politics’.

The emphasis here is mine. Does any anthropologist (including David Boehm) insist that humans all ‘chose to live just one way’? And if so, what exactly does that mean? What do we mean by ‘chose’? And what do we mean by ‘one way’?

In my mind, what we have here is strong rhetoric that insists on a point that no one is making. Similarly, what does it mean to insist that for tens of thousands of years, ‘nothing happened’? Does any serious social scientist actually insist that?

Of course, many authors make strawman arguments. But it’s particularly annoying to see it happen in a book that’s claiming to write a new history of humanity. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. So far in Dawn, I’m underwhelmed by the quality of the evidence, and annoyed by the tone of arguments, which don’t seem to seriously engage with the theories they criticize.

One last thought. I find the use of the word ‘political animals’ revealing. If humans are evolved animals, it follows that we have not always been political. No other animal has politics like us. So where did we get our politics? This, to me, seems to be a gaping hole in Dawn: skirting around issues of evolution without a serious engagement in evolutionary theory.

After some consideration, we’ve decided that two-factor identification is overkill for forum users. We’ll keep it for site admin, but everyone else can just login with their passwords.

-

AuthorReplies