Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

A couple of quick hits, late to the party, in a really great thread:

Brian–

On stakeholder theory & Corporate Social Responsibility: The social control matrix that these concepts would necessitate to have any real effect on corporate governance is so expansive and so adverse to the current system of absentee ownership that the terms are rendered meaningless as a basis for reform. You’d need to go far beyond simply voting for politicians who create and uphold regulatory laws: you’d have to develop a corporate structure that combines a worker-directed cooperative enterprise, a consumer cooperative, and direct input from those constituting the greater public affected by the operation and logistics of said corporation—and, further, allow that entity to make decisions for all the interlocking corporations that must exist up- and down-stream of the corporation in question. At that point, you’ve basically incorporated a commune (and good for you!) so why not lean into it?

On Galbraith’s call for government’s countervailing force: Your parenthetical about “business judgement rule” effectively puts the lie to that, demonstrating that the courts specifically (and government more broadly) operate from shared worldviews and according to the same operational frameworks as corporations. More on this could be gleaned from Robert Jackall. The jurisprudence you mentioned is an integral mechanism in the modern capitalist engine. Talking about the possibility of creating a countervailing force as a potential reform rather than an improbable revolution misrepresents the realities of the present and the lessons of the past. The state and its laws is what enables corporations (especially massive, dominant, differentially accumulating corporations) to exist; it was never designed to be what reins them in, only what keeps them running, growing, and reifying with the fewest bumps. More on that could be gleaned from David Graeber.

Scot–

On the Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery: It could also be called something like “The Continually, Unendingly Self-Reproducing Expansion of Society’s Tendency Toward Meritocratic Expert-ification into All Aspects of Life as a Means of Legitimizing its Paradigm of Rule Despite All Evidence to the Contrary” if that wasn’t so long and horrible, but it still wouldn’t directly hit on the fact that the paper is largely about innovations in symbolic representation and Ulf trying to define enormous German words/concepts. I’m of the mind that big ideas sometimes require big words so expressing them doesn’t get overly cumbersome.

On why capital being power matters: Life still could look like building physical pyramids for our rulers instead of just pyramids of control. It also means, because capital can’t be anything other than power, that any society with capital will inevitably be a society where people are empowered based on their accumulation of capital. Without capital, power and its expressions will obviously still exist but would need to be mediated through other forms. What those forms might be, however, is tough to say until they’re wrenched into being. Sounds like yet another revolution in waiting. Otherwise, asking what life might look like if capital weren’t power seems hollow, since it is and can’t not be.

Ishi/JMC–

On films about capitalist development: Have you ever seen Norman Jewison’s 1975 film Rollerball? If not, you should!

- This reply was modified 4 years ago by Jeremy Zerbe.

Really glad to see this topic be posted here. I’ve been taking notes for a while now on a CasP conception of class (but have yet to build them into anything comprehensible) and I think this is a great inroad to that conversation.

One potential argument I see here is a refrain I’ve heard elsewhere on this forum that the logic of capitalization effectively “rules” even the ruling class. But because they are the ones with the power to creorder that logic, I think a differentiation must be made to avoid obfuscation of the societal roles of the capital-powerful.

Your paycheck-to-paycheck definition of the ruled seems to align with Mao’s “Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society” from 1926, when he explains the stratification of the petty bourgeoisie whose upper crust includes those with “surplus money or grain, that is, those who, by manual or mental labour, earn more each year than they consume for their own support.” Worth noting, however, is that Mao identifies even that top level (along with the lower petty bourgeoisie, who “are undergoing a gradual change from a position of being barely able to manage to one of living in more and more reduced circumstances”) as potential allies in the revolution, so long as they are not persuaded by their proximity to the more successful and stable middle bourgeoisie.

Perhaps this definition of “petty bourgeoisie” accounts for this gap between the 70% without surplus and the 95% of lowest net-worth individuals that you highlight? Without getting too productivist (and keeping in mind the divide presented in CasP between “business” and “industry”), I believe that if you looked deeper into who constitutes that gap, you’d find that most work in the realm of business rather than in an industrial capacity—or, if they are in the latter, then generally as low- to mid-level managers.

Your point about systemic fear I think is particularly well-founded. I’d say that the threat of systemic fear quickly evaporates as you move out of the ruling class and those whose work depends on their stability (the middle bourgeoisie, if we’re willing to use that term at this point) since there’s less-to-nothing to lose for those without capital or, as they might call it, “skin in the game.” Lower classes might recognize systemic fear or responses to it, but it all just appears as part of “the game” of an economic order they’re largely not part of.

Excited to see where this line of questioning/thinking goes!

- This reply was modified 4 years, 2 months ago by Jeremy Zerbe.

My answer to the question posed in the last sentence of the abstract above is ‘religion’.

People find value and comfort and power in religion and some turn it into forms of capital. Since orthodox economics has the real fake noble prize in econ maybe casp can have the one in religion or powernomics.

Are you familiar at all with Eugene McCarraher’s The Enchantments of Mammon?

Book here and one of the many podcast/interview appearances he did on the book here. I haven’t read it yet but it’s on my list after having listened to another fascinating interview he gave Lewis Lapham. A lot of what he talked about there resonated with my reading of CasP, especially about advertising and organization management.

It’s no mystery that CasP uses a religious tone to describe the “ritual” of capitalization at the heart of the capitalist system, which Blair Fix goes into great detail about here. Of particular note from that much broader article:

If [the capitalization] ritual seems arbitrary, that’s because it is. There’s nothing objective about the capitalization formula. It doesn’t point to any fundamental truth about the world, either natural or social. The capitalization formula is simply a ritual — an article of faith.

This arbitrariness doesn’t lessen the importance of capitalization. Far from it. Rituals are always arbitrary. But their effects are always real. Just ask Bob, who’s about to be ritually sacrificed to appease the god of rain. The ritual is arbitrary — founded on a worldview that is false. Killing Bob won’t bring rain. But the rulers believe it will. And so Bob dies. The ritual is arbitrary. The effects are real.

The capitalization ritual works the same way. The formula is arbitrary, as are its inputs. But that doesn’t matter. What’s important is that people believe in the ritual.

And the subsequent embedded quote from CasP:

Faith in the principle of capitalization now has more followers than all of the world’s religions combined. It is accepted everywhere — from New York and London to Beijing and Teheran. In fact, the belief has spread so widely that it is now used regularly to discount not only capitalist income, but also the income of wage earners, governments, and, indeed, society at large.

Either way, McCarraher’s is another long book you could read with a tumbler of wine under the shade of a tree.

February 26, 2021 at 3:48 pm in reply to: GameStop, hedge funds, and the “reality” of the stock market #245393Thank you Blair for sharing those pieces from Doctorow (love him) and Di Muzio, and thank you Jonathan for sharing that bit from your 2018 paper, which I ended up reading in full—and serendipitously so, because I’ve been thinking a lot lately about CasP with regard to both class and praxis. It’s given me much more than just this issue to think about, which I’m sure I’ll return to at some point in a new post here in the forum.

Doctorow’s post was (as ever) very clarifying, but I found Di Muzio’s opinion overly rosy. After all, as B&N’s bridgehead identifies, any truly revolutionary practice within the realm of finance would need to remove money from the power brokers and their market casino and instead plough it into democratically-controlled real assets such as affordable housing if we wish to undermine and delegitimize private ownership and enterprise. While I certainly was rooting for even the richest of these retail investors to knock a hedge fund down a peg, playing within the game is just that: taking a seat at the casino table. It’s not exactly a count-room heist, nor is it burning down the casino. Especially as the $GME price has once again leveled (albeit higher than before), it’s hard to see the events that played out as anything more than a fun news cycle or two before the casino bosses brought everything under control once more.

If the surge from r/WallStreetBets shows us anything about capital as the “organized power of a firm to shape and reshape the terrain of social reproduction,” it’s that while ad hoc “firms” of like-minded and like-intentioned individuals can, with enough organization, affect some degree of change for some amount of time, their ability to actually upset an established feature of capitalist society is, of course, extremely limited. The stock market is the very center of value creation and capitalist power, and so it was always going to be tough for a bunch of people on Reddit to make something stick. Nor was this ever really their intention.

This brings me to B&N’s bridgehead. I think the pension-housing idea contained within is a useful one, a smart one even, and I recognize that the whole point being made is that research must be done to develop other, interconnected plans and to show how they are viable. However, the concept runs aground in the same place as the $GME short surge for me.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of total US workers participating in pension plans in 2018 was only 21%, while a mere 12% of private-sector workers do so. Retirement savings plans like 401(k)s, on the other hand, are contributed to by 43% and 47% of workers, respectively. Even a massive movement of pension money toward a revolutionary financial project like that suggested would be frightfully insignificant. And that is without even considering the proportion of workers who can actually control where those funds go through some means of workplace democracy. The most substantial amount of the pensioned work in state and local governments (comprising just 19 million of the US’s total 139 million workers). There, 76% of workers participate in pensions compared to a scant 17% who contribute to 401(k)s.

Perhaps, then, this small but focused sector is the lodgment of the bridgehead. To make progress here, however, would likely mean making this an investment project of the state, or at least the continually-beleaguered public sector unions. Public banking might provide a solution, but while that issue has become one around which socialist debt and finance discourse and action increasingly revolves, it’s beset by the same issues and interests that this bridgehead is. After all, these are by no means lucrative propositions, and while the existing solutions are, we can all agree, inadequate, they are still, for most people, sadly good enough—at least in their own estimations. As a friend I shared this bridgehead proposal with said:

That sounds nice but I don’t know how you convince people to agree to drastically reduce the returns on their pensions and consequently their ability to retire.

The left has to have a better offering to people than the people with capital do. They’re offering huge percentages of wealth increase (relatively) to those who have money to invest or pension plans, in exchange for making the wealthy drastically wealthier. The left answer can’t be “We’ll make you less wealthy but you’ll help people even worse off than you,” if you want to get people to actually do this.

Outside of taking money from the richest of the rich, we’re hurting people who don’t have enough to help people with even less.

How, then, to break the “nearly total leverage [capitalists] have over middle-class incomes and the middle-class way of life” when middle-class disinterest is as hostile to change as the oppositional interests are? How to get people to resist the possibilities of the casino table even when the realities of the game being played are so fraught and winnings ever worsening? How to develop organized social power great enough to begin to create a new kind of society without the requisite capital flow (let alone accumulated capital) to creorder it?

There seem to be a great number of carts to put in order here, and no horse in sight.

- This reply was modified 4 years, 4 months ago by Jeremy Zerbe.

January 19, 2021 at 1:18 am in reply to: Control over skill realization: A response to Fix in RWER (2019) #245223I just wanted to drop back into this thread because I picked up Moral Mazes and have been reading it for the past couple of days. It’s excellent so far and I think it would be a worthwhile read for anyone here, especially Blair. It absolutely does provide a great deal of groundwork for a “Theory of the Corporate Class” and even refers to Veblen in the endnotes.

For a taste, here is a quote from the introduction in which the author Robert Jackall talks about what I’ll call the creorder of bureaucracy:

Bureaucratic work shapes people’s consciousness in decisive ways. Among other things, it regularizes people’s experiences of time and indeed routinizes their lives by engaging them on a daily basis in rational, socially approved, purposive action; it brings them into daily proximity with and subordination to authority, creating in the process upward-looking stances that have decisive social and physiological consequences; it places a premium on a functionally rational, pragmatic habit of mind that seeks specific goals; and it creates subtle measures of prestige and an elaborate status hierarchy that, in addition to fostering an intense competition for status, also makes the rules, procedures, social contexts, and protocol of an organization paramount psychological and behavioral guides.

And then, from the first chapter, as Jackall lays out the historical context that has given rise to bureaucracy:

No major occupation or profession in our society has escaped the process of bureaucratization. They are all—from assembly-line workers to physicians—specialized, standardized, arranged in a hierarchy and coordinated by higher authorities. Moreover, bureaucracy is never simply a technical system of organization. It is also always a system of power, privilege and domination. The bureaucratization of the occupational structure therefore profoundly affects the whole class and status structure, the whole tone and tempo of our society.

Now, these are more general observations on hierarchy than Blair’s research around hierarchical levels and their effect on pay, but as the book continues, Jackall dives deeper into the actual “skills” and “responsibilities” of the upper echelons of the corporate structures of the firms in which he was embedded. What he finds, of course, is that these skills are negligible, the managers themselves nearly interchangeable (by design), and that the defining feature that gets one promoted or sidelined is how “comfortable” they make others above and around them feel. This is a refrain to which Jackall and his subjects constantly return.

[A manager] makes other managers feel comfortable, the crucial virtue in an uncertain world, [by] establish[ing] with others the easy predictable familiarity that comes from sharing taken for granted frameworks about how the world works.

If there really is a “hidden skill” to be identified, it must certainly have to do with exuding this notion of comfort. Though how that would begin to be quantified or even qualified is well beyond me.

All in all, a really fascinating book. While it has definitely aged a bit, it has much to offer on these topics, including institutional waste which has been a particular interest of mine for a while (and about which I may return to this thread again later). My copy is a Twentieth Anniversary Edition with an afterword about the financial crash of 2008-09, so I look forward to Jackall’s update. Thanks again Dominic for the suggestion!

How much difference do you think the ongoing economic reorganization toward already dominant, quarantine-readied businesses like Amazon, Walmart, etc. during the current health crisis will make for this regression trend?

Will it be just another blip upward in a continued dampening of the annual rate of change? Or will we see it explode upward again, possibly kickstarting a newly expansive rate of change for these increasingly powerful dominant firms as small(er) businesses that may have once provided competition continue to fold? To that end: does this annual rate of change graph look about the same if viewed with the top 50 firms rather than 200? What about the top 10?

An additional, sort of sillier question: Is this tendency for the annual rate of change to regress the CasP version of Marx’s tendency for the rate of profit to fall?

December 29, 2020 at 11:42 pm in reply to: Control over skill realization: A response to Fix in RWER (2019) #245165Thanks for the suggestion, Dominic. This book looks fascinating. The quotes pulled from it in that Wiki article ring particularly true to me, and I’d bet it would make a good partner to Bullshit Jobs which I still haven’t gotten around to.

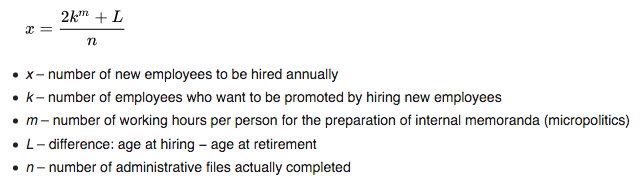

I noticed that the famously illustrative Peter Principle was linked as a related article, along with one that I’d somehow never heard given a name before: Parkinson’s Law, or the idea that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” The idea there is simple, but I was interested in the formula provided and how it might relate to the capitalization formula that’s put forth in CasP—in particular because it has to do with the growth of employees and the direction of their efforts.

Since it expands well beyond the bounds of CasP’s quantification (and, like most business “laws,” is veiled in a degree of irony), perhaps there’s nothing there. However, variable x clearly relates to CasP variable E (and the volume of employees that factor into it); variable k seems to coincide with Blair’s studies in hierarchy and income; and variables m and n seem to relate to sabotage in some form.

Worth a thought? Or am I grasping at straws here?

December 7, 2020 at 3:59 pm in reply to: Control over skill realization: A response to Fix in RWER (2019) #245113Thanks for your response, Blair. I think your walkthrough of the causality between skills and hierarchy here is clarifying. I was a little concerned that my focus on the “realness” of skill acquisition might be taken as a defense of human capital theory (which is mechanistic, intangible, unquantifiable and, frankly, bunk), so I’m happy that our understandings dovetail here.

I agree that a “Theory of the Corporate Class” would be a welcome addition to our line of inquiry. I think it would likely pick up from Veblen’s analysis of the lower leisure class whose non-industrious work exists to maintain the leisure, expand the control and, ultimately, spend the money of the upper class. As I’ve been reading his Theory of the Leisure Class, that’s how I’ve been thinking about the modern “business” work that those of us in corporate jobs do in service to owners of those corporations. It’s not quite a 1-to-1 comparison but it’s been illustrative to me. After all, aren’t our corporate overlords the new gentry and their brands the livery of servility?

-

AuthorReplies