Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorReplies

-

November 26, 2023 at 12:27 pm in reply to: CasP RG v. 1.01: Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn Of Everything #249880

Hi all, jumping in late here, spurred by Blair’s contributions.

The aha! for me from the book was the huge political diversity (more, less, differently, and even seasonally hierarchical/egalitarian) of pre-historic/-literate societies — discernible, with careful interpretation, from the archaeological record. Wengrow contributes much fascinating fact and detail to Graeber’s more-overt ax-grinding/politicized approach.

G&W’s claim about Boehm that Blair highlights: Humans as political animals. Key line:

“Boehm assumes…we were strictly ‘egalitarian for thousands of generations’”

This is a bad overstatement; Boehm never uses the word “strictly.” In fact he points to prehistoric societies that were more hierarchical, and discusses societal traits and material conditions that are contributive or necessary to more hierarchy.

But he does say quite explicitly in the introduction to Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior:

“I make the major assumption that humans were egalitarian for thousands of generations before hierarchical societies began to appear.”

So his hierarchical examples can be (cynically?) viewed as rare exceptions, “now, to-true-true”-isms.

So Boehm very much does participate in the widespread Rousseau-istic noble savage business that I and I think innumerable others have ingested through osmosis in our non-expert intellectual travels. And as G&W point out, that does conflict quite oddly with Boehm’s Aristotelian view of humans as The Political Animal. Were humans not political (much) before the neolithic revolution?

G&W’s claim, that according to Boehm, “for about 200,000 years political animals all chose to live just one way”, is another unfortunate overstatement. But “mostly one way” would not be.

G&W forcefully make the point, with many examples, that pre-neolithic humans had hugely diverse (and sometimes large) political structures, with huge variance even in adjacent tribes — often in fact, in direct response to adjacent (hierarchical) structures that they disliked/disapproved of (see “schismogenesis”). I didn’t know that.

That was a super-interesting and useful understanding for me, and a valuable corrective to lurking simplistic Rousseau-ism that is still quite intellectually pervasive — with significant help from Boehm.

Thanks for listening…

I’m actually more curious about another part in the referenced Debreu nobel paper: the commodity vector part.

I just don’t understand how a vector emerges, or what the vector space means, when each commodity has a different unit of measure. Is the space (almost) infinitely multidimensional, or…?

Thanks,

Steve

I also struggle with the issue of “justifying” income, and 100% agree with your #2 — that attempts to quantify work-hours’ contribution to production of stuff is fruitless. Because, there is not even a conceivable common unit of measure for heterogenous “output.” What’s actually measured, what can be measured, is spending/purchases (and their obverse, income). It’s silently assumed that that $ measure equals the “value” of production/output, labeled “GDP” and ubiquitously conceived as “real” even though it’s imputed from measured spending goshdarnit.

That questionable practice doesn’t disqualify the actual spending and income measures, however. They’re very “real.”

The fact is that in 2020 in the U.S., 142M people worked 244B hours, and received $11.6T in compensation for that work. (All “estimates” of course, like all accounting measures; some are more solidly-grounded estimates, some less.) In very real practice, those hours, efforts “justified” that income. (And we have the means to categorize/analyze that income in many ways — by income or wealth percentiles, age, race, etc. etc.)

Meanwhile in total people received $16.6T in income (plus $11T in accrued holding gains not counted as “income”). That’s $5T–$16T in income that is explicitly not “justified” by hours worked/human effort, at least in this tabulation. Tax treatments and diverse other institutional practices certainly make this earned/unearned distinction, with real import for people. It not just theory; it’s ubiquitously practiced.

To raise a topic that has better “legs,” IMO, than the two issues/examples you’ve raised. This is usually discussed in terms of “proprietors’ labor compensation,” as part of their “mixed income.” Shouldn’t some portion of their apparently non-labor ownership income be categorized and “justified” as labor income, even though they don’t report it as such (for perverse tax reasons)? My personal answer would be yes, sure — for important analytical reasons even though it slightly undercuts my preferred progressive rhetorical stance.

Income accountants/economists have been interrogating the issue for more than a century. There’s a good 2017 BEA discussion here. Piketty & co.’s approach to the issue is well explained here. It’s been addressed innumerable times in issues of the Review of Income and Wealth going back to ’51 and the work of Kuznets & co.

But yet again: even the most extreme attribution of proprietors’ mixed income to labor only shifts the labor/ownership shares by a few percentage points. It’s an edge case, pretty small magnitude, and IMO doesn’t justify saying that earned/unearned income is “unmeasurable.”

As for the far broader claim in #1 that owners “may offer” — that ownership income is “justified” as recompense for past labor (plus let’s not forget their “patience” and deeply virtuous abstinence in hoarding their wealth… #GotMarshmallowTest?) To keep this brief I’ll just say it’s purely specious and self-serving, like so many justifications trotted out by the ownership class going back to time immemorial. That they might (do) make that specious argument provides no reason, IMO, to accept that argument as disproof of a thoroughly well-considered distinction between earned and unearned income, measured/estimated with quite excruciating care.

Thanks for listening…

Steve

- This reply was modified 3 years, 7 months ago by Steve Roth.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 7 months ago by Steve Roth.

>earned income = income of those who participate directly in production.

“Of those” implies a defined class or category of economic actors. I’d define it differently, just categorizing (household/personal) income.

Income received in recompense for human effort.

This is the kind of categorization and labeling that accountants do constantly, in innumerable realms and situations. In practice the huge bulk of personal/HH income (even including what I call comprehensive [Haig-Simons] income) is straightforwardly measured and categorized by that criterion.

There’s 1. earned labor compensation, and 2. all the rest (unearned), which we can categorize as A. (net) gov transfer income, or B. property income received in recompense for owning stuff. Most of this is easily assembled from the national accounts.

There are remaining judgment calls, for sure, comprising maybe 15% (?) of HH income. But again, even with fairly extreme accounting choices there, the labor/transfer/ownership split only shifts by a few percentage points.

We can certainly interrogate the concepts, methods, and measures used in the national accounts. But I don’t think we can reasonably say that earned/unearned income are unmeasurable.

>don’t owners of land — the most notorious ‘rentiers’ — provide inputs to production, as do owners of ‘capital goods’?

Putting aside eg landlords’ and other owners/entrepreneurs actual management and other work on directly owned properties/firms, which is properly seen as earned income (but which is often not reported as such to the IRS by owners/landlords because our tax laws are stupid; cf Bezos’s $88K a year in reported earned income):

Owners only provide “inputs” in the wildly stylized sense used in many econ models and silently in ubiquitous mental models. An Amazon shareholder is literally treated as if they own warehouses directly, and they’re selling capital services provided by the warehouses to the corporate entity. (Capital services are reasonably conceived as inputs to production, IMO.)

Shareholders “own” the warehouses, and they’re sacrificing their own use of the warehouses so Amazon can use them, so they’ve justified or “earned” that income without actually doing anything. Hope you’ll understand why that seems like a pretty crazy, far-fetched abstraction to me.

(Irresistible aside: if we take humans’ inalienable, self-owned “human capital” seriously—the long-lived productive stocks of goods that we call health, abilities, skills, knowledge, etc, produced through investment spending on health, education, home caregiving, many et ceteras)—then workers are also selling their capital services as inputs to production, when they work for wages. This, I should add, is the overwhelmingly dominant capital-services input to production, measured in $ magnitude…)

But really c’mon: household shareholders, bondholders, REIT owners, do nothing but…own financial instruments (including titles to real estate). That’s what they’re compensated for: just owning stuff. There’s ~zero human effort involved. (Their arms-length hired management does all the work, presumably and properly reporting their income as earned; owners get the remainder/profit.)

Ownership, in and of itself, is not an input to production.

In the “real,” empirical, and extremely measurable world of monetary values (income, assets, etc.), we can draw a quite bright line between most earned and unearned income. Even if there’s also a large (15%?) gray area. And we could shrink that gray area. Suppose earned income were taxed at a lower rate than unearned. Asset owners would jump all over themselves to report their (justifiable) hours actually worked, to qualify income as earned for tax purposes. (Maybe they’d even do more work; incentives matter, right?) Just one example.

At its most extreme and strained, you hear meritocratic justifications about wealthholders’ annual hour or so spent rebalancing their portfolio, as doing the noble, necessary social work of “asset allocation.” As a very moderately wealthy person living almost wholly off of (unearned) returns to my wealth, I just can’t even.

Hoping this helps clarify the frame in which I’m thinking, trying to understand all this stuff…

- This reply was modified 3 years, 8 months ago by Steve Roth.

>Please share, Steve!

I realize that that blanket offer may have been overambitious. Quite a lot to unpack. I will say that understanding sectors as economic units is key. Also the relationships between sectors, households in particular. They are the top of the accounting-ownership pyramid; all firms’ equity-ownership shares, at market prices, are included as assets on the household-sector balance sheet. (Putting aside the rest of world (ROW) sector for the moment.) The HH sector is also where the primary import of accounting stocks and flow “comes home” in human lived experience across lifetimes, families, and dynasties.

I have some issues with some constructions and implicit presumptions of national accounting presentations, but full credit where due: they’ve been thinking really hard about what their measures mean, and how to best present them, since Kuznets and co. in the ’30s. Most significantly this century in the 2003, UN-sponsored System of National Accounts. There’s “a vast literature” on how we can think about and understand this stuff in numeric, monetary terms.

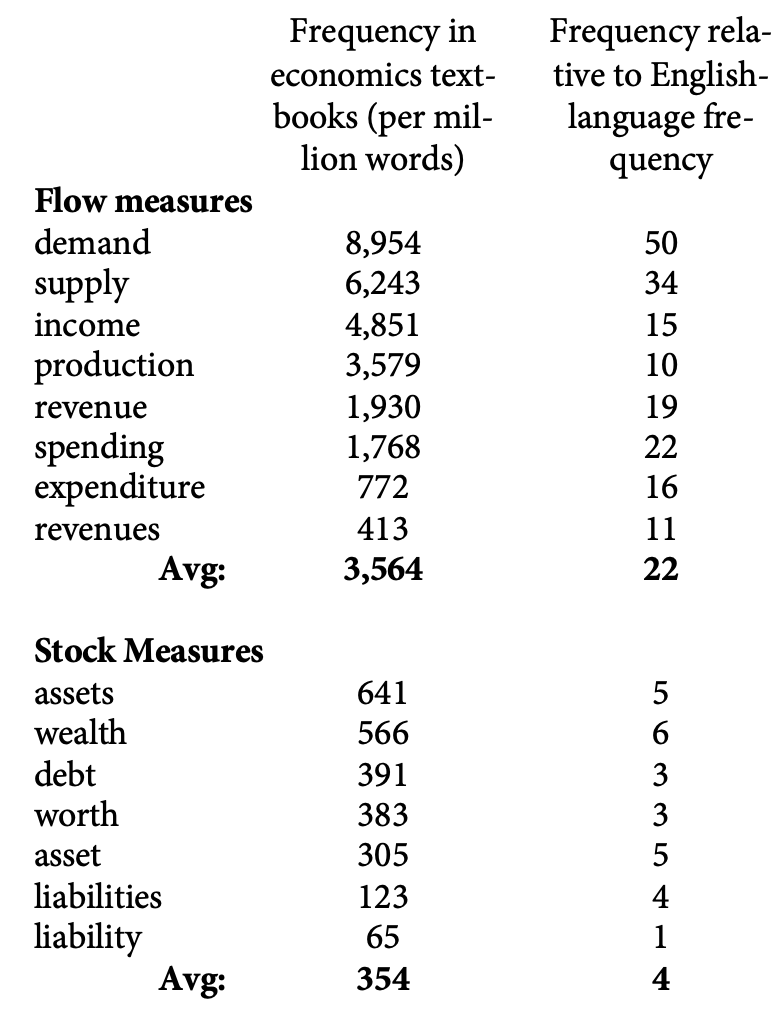

Meanwhile, yes what Troy said. Accounting (and business) classes don’t even count as electives for econ majors at Harvard, MIT, or U Chicago. etc. And as for the “balance-sheet-complete” national accounting that I constantly bang my spoon on the high-chair about, here are some word counts of accounting terms from econ textbooks—with full credit to you (!!) for giving me the ability to do these counts.

(Note that >50% of the flow terms shown here are the dimensionless abstractions supply and demand—not actually measures but imagined curves.)

I’ve pondered for a while putting together a teaching unit on accounting for econ classes. Thinking the key understandings could be imparted in maybe two weeks (?), ten hours of class time.

Okay stopping there. A more narrow and fulfillable offer: I’d be happy to answer more specific questions about national accounting that I may have answers to.

In the meantime, I’m just polishing up the following, which gives detailed derivations of “personal income,” and its relationship to personal-sector balance-sheet assets. I hope in very clear terms. Short-form takeaway: “saving,” as constructed, completely fails to explain asset/wealth accumulation.

Thanks,

Steve

I’d just like to revisit, (disagree with,) and revise two statements that arise here, which I think are importantly incorrect:

Blair (10/29/2020): “the concept of ‘unearned income’. That’s a fundamentally unmeasurable concept.”

Troy (4/28/22): “there is no means to distinguish between productive and unproductive income, earned and unearned income.”

Revision: “there is no means to distinguish *perfectly* between…”

It’s quite straightforward to extract these earned/unearned measures from the national accounts’ household tables. (It’s much more difficult, and may well be impossible, through the lens of the corporate sector. The attempt itself arguably participates in the “valorization,” lionization, even deification of “producers” cum “entrepreneurs” cum “capitalists.”)

Start with a basic statement that’s quite straightforward both for broad rhetorical purposes, and as a precise, technical, economic (and accounting) term of art: Earned income is received by households, people, in compensation or reward for doing things: providing inputs to production. The remainder, all other tallied household income, is unearned.

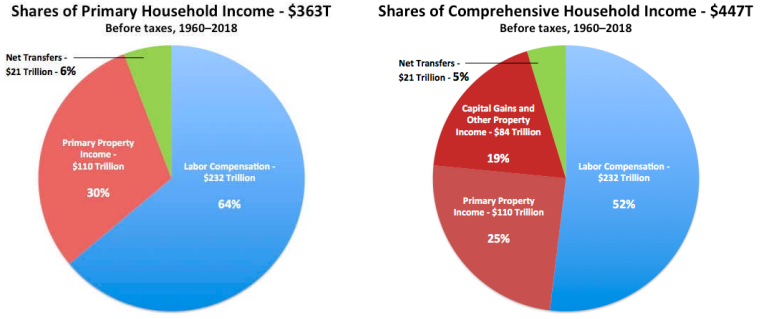

Then divide unearned income into two categories: income received for owning things, and income received as social transfers. These categories are all straightforwardly visible and summable in national accounts of the household sector. Here’s a look at that. It’s just a rearrangement and relabeling of the Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts’ household Table S.3.

(The righthand pie shows comprehensive, balance-sheet-complete Haig-Simons income, which includes $10s of $Ts in holding gains accumulated by owners purely for owning/”holding” stuff.)

There are accounting judgment calls and measurement issues lurking behind this (I’d be delighted to share what I know of those), so it’s not some perfect picture handed down from Mt. Horeb. For 20 years, eg, Jeff Bezos claimed $88K a year as earned income on his tax returns. But (I’ve run the numbers) giving “credit” to “entrepreneurs” for the untallied value of their labor “contributions,” inputs to production, even at its most extreme estimation, would only shift the earned/unearned percentages above by a few percentage points. There are many other etcs, but the proportions you see here are quite solid.

IMO, “unearned” carries all the rhetorical and moral baggage we need, in a usage that most/all can grasp at a glance. And the fairly simple deconstruction above is at least a very close approximation of what’s needed for theorists, empirical researchers, and modelers: a technical term of art that’s precisely defined by a whole web of mutually coherent accounting identities.

So IMO “rent” is just unnecessary for either purpose, and even contributes to the fog of obfuscation and diversionary chaff that is a dominant tool employed by the ownership class to accumulate and maintain its wealth, power, and privilege.

- This reply was modified 3 years, 8 months ago by Steve Roth.

Disappointed to see the 6K minimum word count on this. I have a topic in mind but fairly sure I won’t want or need that much to present it, wouldn’t want to expand it artificially to conform. 6K is close to the maximum word count for many journals, word counts/length have arguably gotten quite excessive in recent years/decades, and heck, Akerlof’s Market for Lemons is less than 5K.

>banks can meet demand for equities by increasing loans, and when these loans become deposits, the overall amount of M-assets increases.

Right. Loans create deposits. Back to this topic thread, that’s straight-up accurate MMT-think (not original to MMT, of course). Endogenous money and all that.

I’m mainly going after the monetarists’ nutty “demand for money” explanation of inflation. Borrowers for mortgages, education, consumer goods, and business investment (the huge bulk of borrowing; brokerage margin loans eg are a pittance) are not borrowing because they “desire” more “money” in their portfolios. In most cases the borrowed money goes straight to the seller, never goes near the borrowers’ accounts/balance sheet. They’re borrowing because they have a desire for (households) housing, or education, or consumer goods, or (firms) to produce long-lived productive goods that will yield a profit.

>4. My point here is that M-assets are not the only ‘means of payment’, so this is an insufficient reason to use only M-assets in money-based theorizing of inflation.

Totally agree, but I’d explain it differently: people don’t spend because they have a lot of M assets (nor do they rebalance M-asset proportion in their portfolios through borrowing and paybacks). People buy fancy cars because they have lots of assets (and/or hopes/expectations of accumulating them). Swapping variable-priced assets for M assets first is just a mechanical necessity because sellers demand M assets in payment.

I think talking about “M assets,” straightforwardly defined as fixed-price instruments, eliminates a whole raft of confusions in these conversations that arises from vague, gestural, and constantly shifting meanings of “money.”

- This reply was modified 5 years, 1 month ago by Steve Roth.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 1 month ago by Steve Roth.

@Jonathan Nitzan:

>It seems to me that so-called M assets…should not have a special role in monetary explanations of inflation.

Could not agree more! In Joan Robinson’s words, “There is as an unearthly, mystical element in [Milton] Friedman’s thought. The mere existence of a stock of money somehow promotes expenditure.” (Which, when “excess” spending bangs against production capacity, causes inflation.)

>(1) It’s true that M assets have a ‘fixed price’ — the $ — but so do all other assets at any given point in time.

? The point of “fixed price” is that the price doesn’t change over time. The price of M assets is institutionally hard-pegged to the unit of account. Not true for other assets.

> (2) The quantity of M assets isn’t really fixed — they are augmented by interest payments,

But, an increase/decrease in interest paid doesn’t change M assets’ price ($s/unit). So there is no price/revaluation effect on the stock of M assets. In that sense, the Q is fixed. (Or changes very slowly and is not subject to portfolio-market effects on Q.)

>their volume expands and contracts with the ebb and flow of credit expansion and contraction.

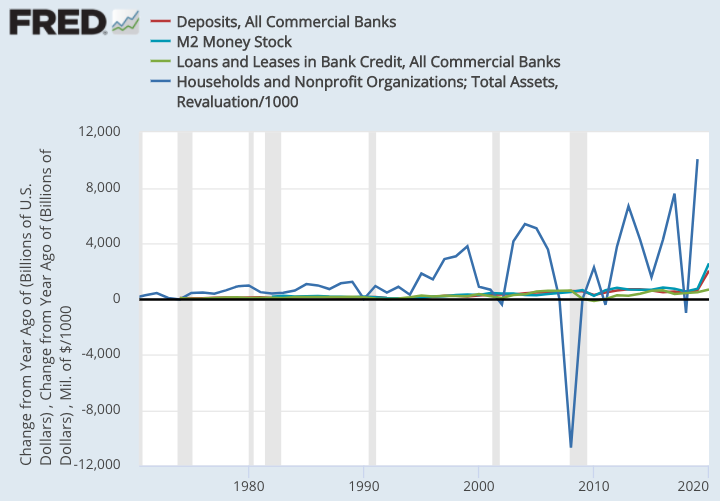

Sure, but unlike variable-priced assets, markets can’t revalue M assets. The M stock can only vary via net new lending (volume change). Which is an order of magnitude smaller than change in total assets, or even just change due to price revaluation. (Which is a key reason why monetarists’ fixation with M assets is misplaced.) These series shows annual changes in $Bs. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=xFpK

(Accounting aside: the only measure we have of net new lending, borrowing minus paybacks, is change in the outstanding stock of commercial-bank loans. Thus we seem to have no available measure of gross new lending, which would seem to be an important measure in economic thinking that prioritizes the effects of lending for investment…)

This interest-rate/volume line of thinking is IMO where monetarists do their biggest linguistic/definitional bait-and-switch: calling interest rates the “price” of money (versus the cost of borrowing — a very different thing). And thus the whole “demand for money” construct: If the market portfolio is long cash eg (cuz portfolio preferences), traders can’t rebalance by bidding down M assets’ price hence total quantity/stock. (And reducing their net borrowing would take years.) They can only change the portfolio proportions by bidding up variable-priced assets — increasing those assets’ total stock and portfolio proportion, and total assets.

>(3) Ultimately, any asset can be converted to an M asset (cash or deposits), and once converted, it can be used for purchases.

Key I think: they are not “converted.” They’re just swapped. Error of composition. If X sells $1,000 in Apple shares to Y for $1,000, there’s still $2,000 in assets out there, just in different hands. Contra the second law of thermodynamics: Financial instruments can only be created, destroyed, and transferred between holders (and repriced!); never changed in form.

>(4) Payment vehicles change.

I’m not sure how this relates, but just to say: Almost all transactions — spending on new goods or asset swaps — involve account transfers of M assets because they’re fixed price. Sellers demand them because they know exactly what they’re getting, at least relative to the unit of account. Ditto transfer institutions; imagine Fedwire, ACH, or Paypal trying to settle nightly accounts if the transferred assets were variable-priced!

But sure, at the margins, a small Q of transactions involves direct swaps of variable-priced assets, without the buyer first having to swap equities or whatever for cash.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 1 month ago by Steve Roth.

>we have to demonstrate that that there was no effort/work/service rendered

When a person/family/dynasty receives dividends and interest (and capital gains) over decades from holding a portfolio of ETFs — unrelated to any imaginable “compensated” labor — wouldn’t the burden of proof fall rather to proving that they had rendered effort/work/service?

This especially as 60% of U.S. household wealth is inherited — so even the wealth from which that ownership income arises is not conceivably attributable to any effort, work, or service rendered. (Unless, at a rather distant stretch, one presumes that “just deserts” are themselves heritable down multiple generations — a distinctly aristocratic notion.)

Both the title and content of a paper I came across today — “Accounting for Factorless Income” — reinforces my sense that in fact the whole “factors of production” construct is untenable and impracticable. Certainly empirically, and arguably conceptually. And thus the standard factor-based definition of rent I bruited above is as well.

So I’m moving to a firm “no” in answer to this thread’s question.

- This reply was modified 5 years, 1 month ago by Steve Roth.

I think it helps clarify to talk about “money” as just one type of asset, or financial instrument, with a particular defining characteristic: these assets’ prices are institutionally pegged to the unit of account.* I call them M assets. (Institutions also make it easy to transfer them between accounts for payments. They can do so because they’re fixed price. Imagine ACH, Fedwire, or Paypal trying to settle payments by transferring variable-priced assets.)

That price-pegging also makes M assets perfectly fungible; deposits at all (US) banks and MM funds are interchangeable.

I think this eliminates a widespread confusion of language that’s well epitomized in John Hicks’ Value and Capital. Some instruments, he says, are “usually not reckoned as securities, but included as types of money itself” (p. 163 in the 1962 reprint edition of the 1946 second edition) — as if they can’t be, and aren’t, both.

M assets, by way, only comprise about 15% of total US wealth/assets.

So speaking of assets (a clearly defined and understood term) rather than money or “funds” or “money values,” a couple of slight edits:

“the accumulation of corporate assets creates new assets.”

“when they expand, they inflate the aggregate sum of assets”

* That price-pegging is guaranteed and enforced by multiple private and public institutions, notably including but not limited to deposit insurance for bank accounts. When the $65-billion money market Reserve Fund/Primary Fund (not insured by the FDIC/FSLIC or any private bank-insurance institutions) “broke the buck” on September 15, 2008, redeeming shares at a 97-cent price instead of $1, the U.S. Treasury stepped in within 48 hours to guarantee and prop up the $1 share price of all money market funds. (The funds paid a fee for this temporary but mandatory insurance, dissolved in September 2009.) In practice, in normal times and even extraordinary ones, $1 in M assets always sells for $1 — by definition here, but more importantly by institutional enforcement. Fixed-price is M assets’ sine qua non — the thing that makes them what they are.

Hope this is useful…

D.T: “all returns to ownership are rent”

Right. Couldn’t agree more.

Starting with this definition of economic rent:

Payments to factors of production in excess of what would be required to bring those factors into production

And focusing on household assets and income, the top of the accounting-ownership pyramid, where the “buck” stops:

All measured HH property income is by definition unearned income, received just for owning things. Otherwise it would be classified as earned labor income, received for doing things. (Yes, some proprietors’ “mixed” property income should by “just deserts” be classified as labor compensation; fine. How much?)

Households’ ownership rights, assets, wealth are not factors of or inputs to production. And even if they were, would wealthholders choose to be less wealthy if returns were lower, starving the production line of that valuable ownership “input”? (What’s the elasticity on that?)

Yes, portfolio churn amongst wealthholders, their collective asset reallocation, does affect what enterprises have/get funds to purchase actual inputs.But does a household’s periodic portfolio rebalancing qualify as significant labor “deserving” of compensation for that “input to production?” Seems “in excess” to me; they’d do that rebalancing anyway, wouldn’t they?

And Blair, yes: just call it unearned income instead?

-

AuthorReplies