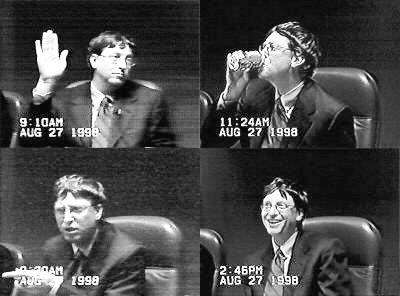

Originally published at pluralistic.net Cory Doctorow Don’t let the sweater-vests and the (dilettantish) “education reform” work fool you: Bill Gates made his fortune through sheer robber-baronry, presiding over a vicious monopolist that shattered the law in its greedy quest for billions and permanent, global dominance. Microsoft’s illegal conduct was so blatant, persistent and obviously wicked […]

Continue ReadingEnd of the line for Reaganomics

Originally published at pluralistic.net Cory Doctorow Reagan turned the country upside-down, in a very bad way. The “Reagan revolution” was indeed revolutionary (or, rather, counter-revolutionary), reversing a half-century of progress on social safety nets, workers’ rights, and environmental protections. When we take stock of the Reagan years, we tend to focus on the actions that […]

Continue ReadingCochrane, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with It? Diamonds and the Accumulation of De Beers, 1935-55’

Abstract What is accumulation? Visibly, accumulation is a quantitative process, demarcated in financial quantities. However, what is the meaning of those quantities? This question has been the subject of great debate within political economic thought. A new theory of accumulation, capital as power (CasP), argues that the financial quantities of accumulation express the distribution of […]

Continue Reading