How Hierarchy Can Mediate the Returns to Education

July 12, 2020

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

In The Social Environment as a Cause in Economics I argued that human behavior has two parts:

- Individual variation

- An environment that acts on this variation

To illustrate these two parts, I used the example of the peppered moth. This species comes in two colors — black and white. Which color is better for survival? It depends on the environment.

On natural-colored trees, white moths are better camouflaged. So being white is better. But on soot-covered trees, black moths are better camouflaged. So being black is better. In other words, the effect of color depends on the moths’ environment.

I think that the same principle is true for human traits. This means that contrary to what neoclassical economics tells us, the benefit of a trait isn’t intrinsic to the trait itself. Instead, the benefit is caused by the social environment acting on the trait.

In the language of causal science, we say that the social environment ‘mediates’ the effect of individual variation.

Mediation

What is ‘mediation’? In The Book of Why, Judea Pearl explains mediation using the example of scurvy. Scurvy is caused by a deficiency of vitamin C. Using arrows to indicate causation, we write:

vitamin C \longrightarrow (cures) scurvy

Long before scientists discovered vitamin C, sailors realized that eating citrus fruit would stave off scurvy. This works, we now know, because citrus fruit contains vitamin C. In causal language, we say that vitamin C ‘mediates’ the effect of citrus fruit on scurvy. Here’s how we write it:

citrus fruit \longrightarrow vitamin C \longrightarrow (cures) scurvy

The important thing about mediators is that when you take them away, the effect of the mediated variable will disappear. In our scurvy example, this would mean creating a citrus fruit that doesn’t contain vitamin C. By removing the mediator (vitamin C), our citrus fruit will no longer cure scurvy.

What mediates returns to education?

Now that you understand mediation, let’s return to economics. One of the most celebrated findings in income distribution theory is the income return to education. People with more education tend to earn more money.

Mainstream economists explain this finding using human capital theory. Education, they argue, makes you more productive. And this productivity then makes you earn more money. In causal language, economists claim that productivity mediates the relation between education and income:

education \longrightarrow productivity \longrightarrow income

In this post, I’m not going to review the flaws in this hypothesis. I’ve done so here, here, here, and here. Instead, I’m going to show you evidence for an alternative hypothesis. I’m going to show you that hierarchical rank can mediate the returns to education:

education \longrightarrow hierarchical rank \longrightarrow income

In this alternative hypothesis, education doesn’t make you more productive. Instead, it’s a tool for climbing the hierarchy. If you’re more educated (think MBA credentials), you can climb to the top of the hierarchy. If you’re less educated (think grade-school education), you’re stuck at the bottom of the hierarchy. The key here is that it’s greater rank that causes greater income, not education itself. Education is just a tool for climbing ranks.

The strength of mediation

Before we investigate how hierarchy mediates the returns to education, I need to backtrack a bit. I need to add more nuance to the idea of mediation.

So far I’ve made mediation sound like an all-or-nothing thing. Remove vitamin C from citrus fruit, for instance, and the fruit won’t prevent scurvy. This is because scurvy is caused purely by a vitamin C deficiency (we think).

In the social sciences, things are rarely this mechanistic. The returns to education, for instance, are likely mediated by many different factors (social norms, government policy, etc.). So when we test if hierarchy mediates the returns to education, the answer isn’t ‘yes’ or ‘no’. It’s ‘how much’. We want to know the portion of the returns to education that are mediated by hierarchy.

To answer this question, we need lots of data — data that we don’t have. Despite the ubiquity of hierarchy, we have almost no data on how hierarchical rank relates to income. So measuring, in a general sense, how much of the returns to education are mediated by hierarchy is out of the question. So I’m not going to do it here.

Instead, I’m going to do something simpler. I’m going to pick one institution and show you that in it, the returns to education are mediated almost completely by hierarchical rank. Think of this institution as a proof of concept for our hypothesis. It shows that hierarchy can, in practice, mediate nearly all of the returns to education.

What’s the institution? It’s the US military.

Administrated pay in the US military

When we study the determinants of income, we usually need to play detective. We have a list of ‘suspects’ — the traits that we think affect income. Our detective job is to dig up data that implicates each trait. We then work backwards to create a formula that tells us how each trait affects income.

When we study the US military, we don’t need to play detective. Why? Because the military tells us exactly how it determines pay.

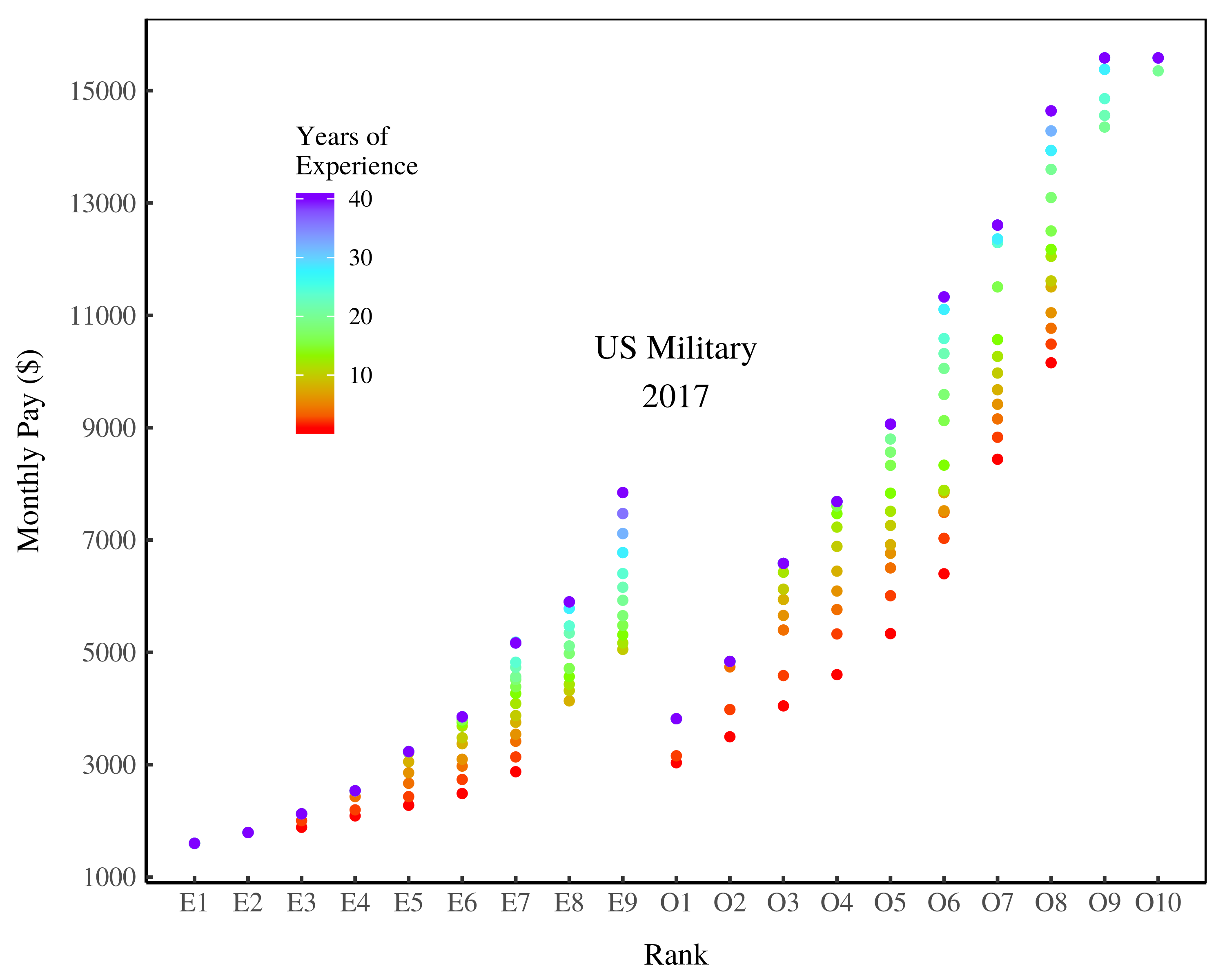

In the US military, income is 100% administered. By this, I mean that there is single document that determines pay, and the terms of this document are administered throughout the military. Figure 1 shows this document — the US military pay grid in 2017.

Figure 1a: US military pay grid in 2017 (monthly pay, 0-20 years experience). From the 2016 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community.

Figure 1b: US military pay grid in 2017 (monthly pay, 22-40 years experience). From the 2016 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community.

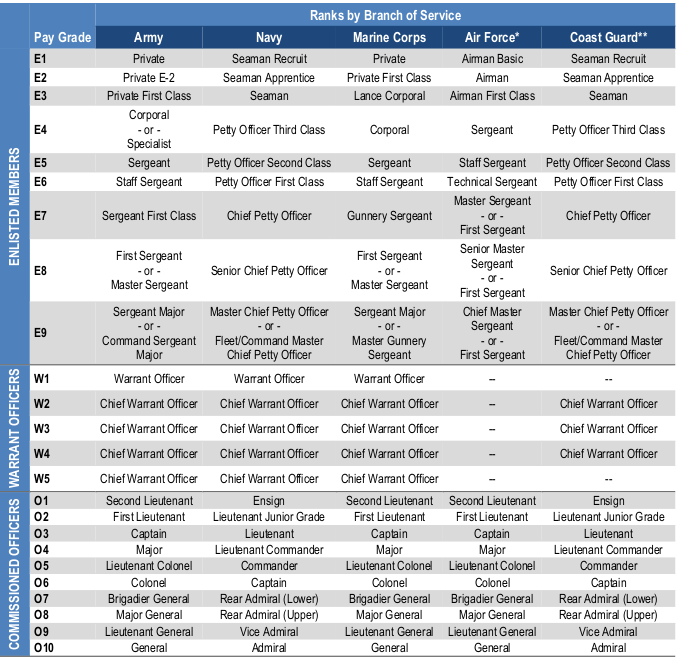

Figure 1c: US military pay grades and ranks. From the 2016 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community.

Looking at this document, you can see that in the US military, there are only two ways to earn more money. Either you advance in rank or you gain experience. That’s it. The US military, it seems, likes to keep things simple.

For my arguments here, this pay grid has two important properties. First, it doesn’t include education. This means that the US military does not directly reward education. So if there are returns to education in the US military, they must be mediated either by hierarchical rank or by experience. There’s no alternative.

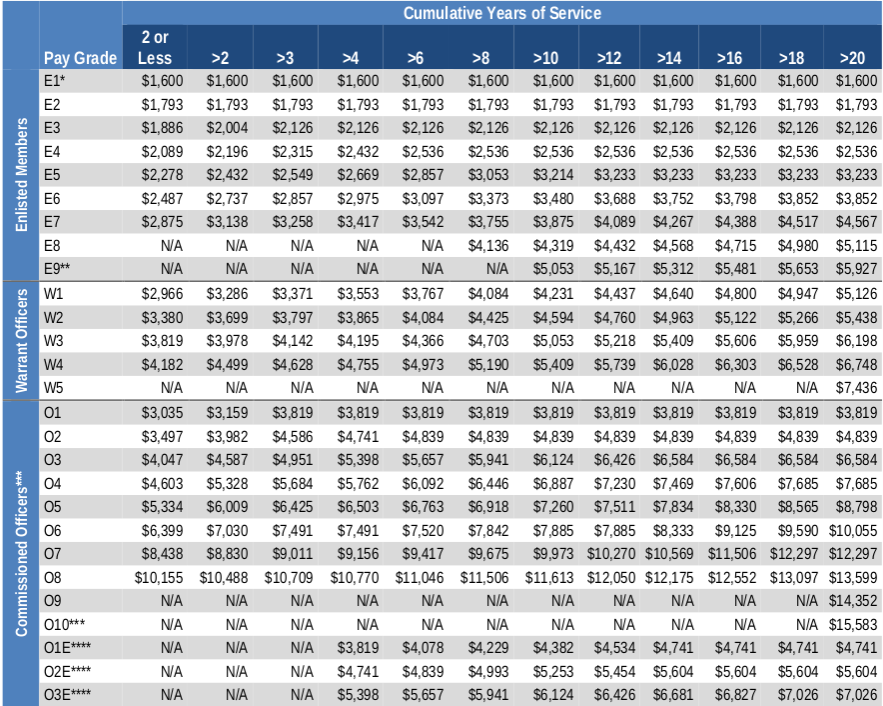

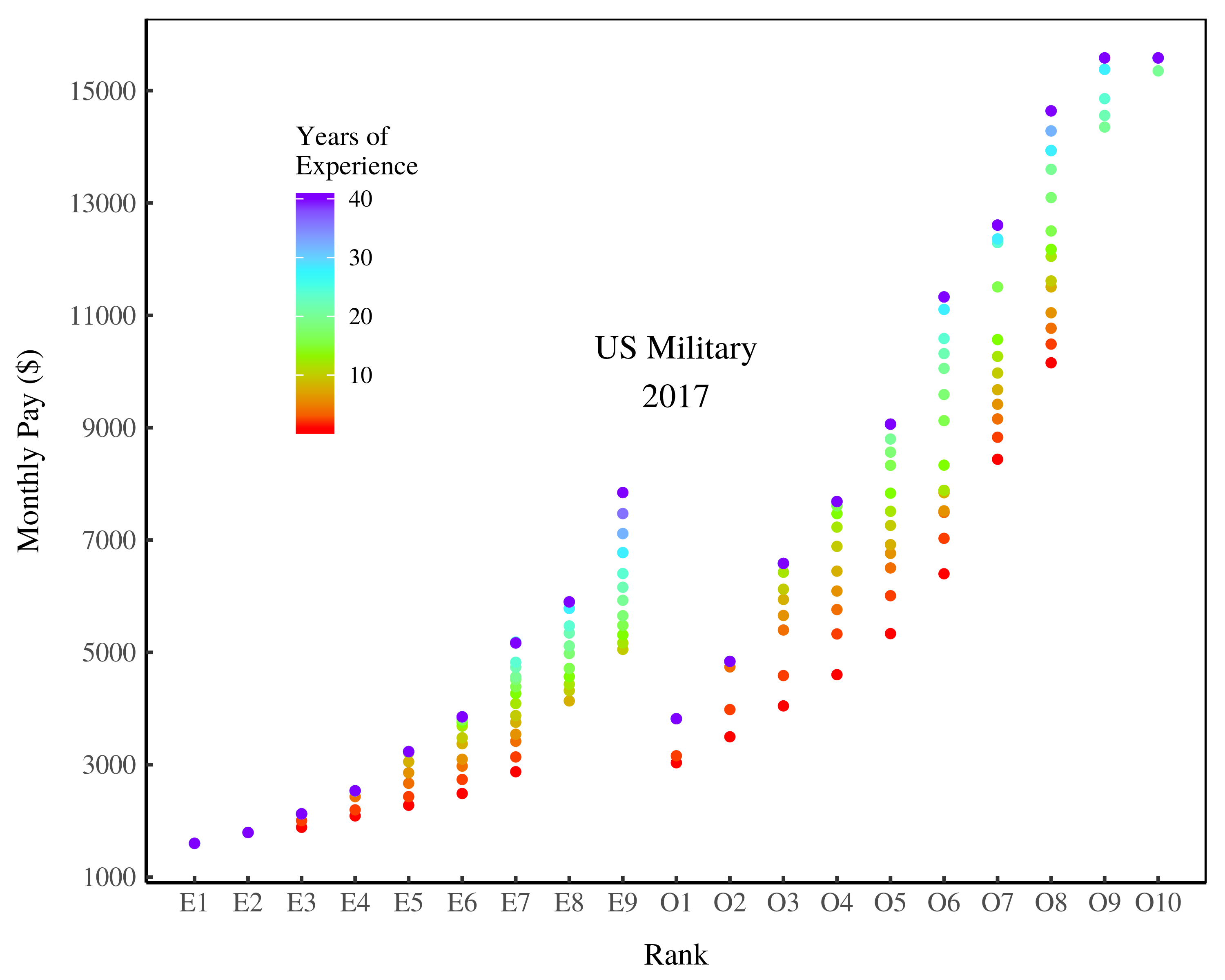

Second, the pay grid tells us that hierarchical rank is by far the strongest determinant of military income. To get a sense for the dominance of rank in shaping income, look at Figure 2. Here I’ve plotted the military pay grid with rank on the x-axis and income on the y-axis. Returns to experience are shown in color.

Figure 2: The pay grid of the US military in 2017. This figure shows monthly pay by rank in the US military. Color shows how pay increases by years of experience. I’ve excluded warrant officers, who make up about 1% of military members. Data is from the 2016 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community.

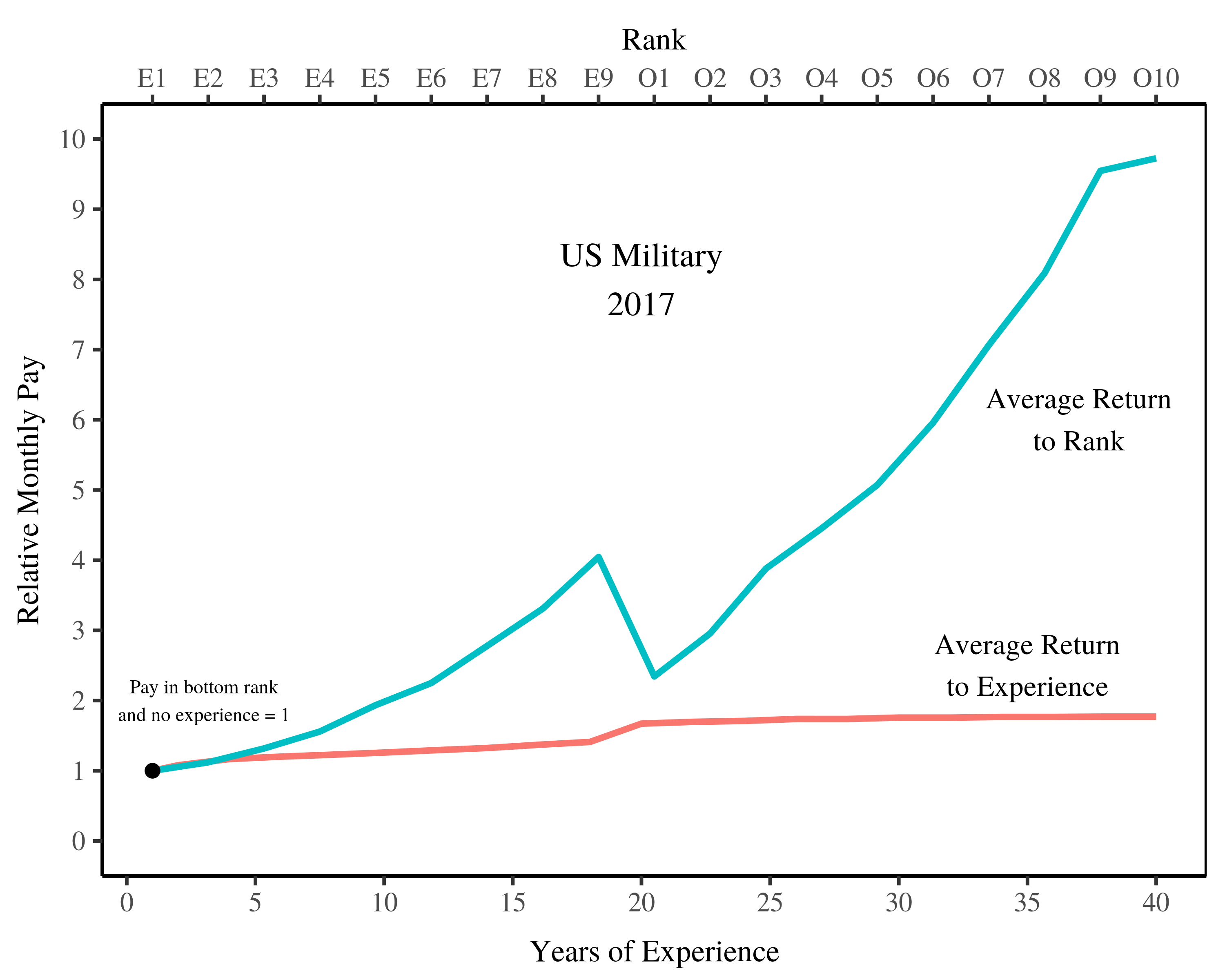

To further put things in perspective, Figure 3 shows the normalized returns to rank and experience. If you max out your years of experience, you won’t even double your income (on average). But if you climb to the top of the military hierarchy, your income will grow by a factor of 10 (on average). The take-home message is that rank is by far the strongest determinant of military income.

Figure 3: Relative returns to rank and experience in the US military. The return to rank shows the average income within each rank, weighted evenly by experience. Returns to experience show average income by years of experience, weighted evenly across all ranks. I’ve excluded warrant officers from the hierarchy.

Education by rank

So far, we’ve established that hierarchical rank dominates military pay. If you don’t advance in rank, the prospects of earning more income are minuscule. So if there are returns to education in the military, they must be mediated almost entirely by hierarchical rank.

The next step is to see if education lets you climb ranks. To do this, we’ll look at education by military rank. Figure 4 shows the distribution of education for three different classes of people: enlistees, officers and 4 star generals. It’s clear from this evidence, that education increases with rank. The vast majority of enlistees have less than a bachelor’s degree. Conversely, the vast majority of 4 star generals have an advanced degree.

Figure 4: Education of US military members by rank. Error bars indicate the variation over the years 2004–2017. Data for officers and enlisted personnel comes from annual demographics reports (Demographics: Profile of the Military Community). I manually compiled the education for 4 Star Generals using personnel listed on Wikipedia.

From Figure 4, we can infer that in the US military, there are income returns to education. If you have an advanced degree, you’re likely to earn more than if you have no bachelor’s degree. But these returns to education are caused by advancement in rank. They have nothing to do with education itself.

Let’s go through the logic again. The only two determinants of military pay are rank and experience. Of these two, we know that rank dominates. Furthermore, we know that military members with higher ranks tend to have more education (Figure 4). These higher-ranked members will earn more money. But we know that this income isn’t caused directly by education, because education isn’t part of the military pay grid.

Instead, the returns to education must be mediated by hierarchical rank. Education allows you to advance in rank, and greater rank causes greater income.

Returns to education explained?

So in the US military, returns to education are mediated almost completely by hierarchical rank. Does this mean we exhaustively understand what causes the returns to education in the military?

Not in the slightest.

You see, in this post I’ve looked only at the first-order cause of income. I’ve taken the military’s administrated pay grid as a given, and investigated the consequences. But if we really want to understand the cause of military income, we need to understand what caused the military pay grid. And that’s a messy question.

The top of the pay grid, for instance, is limited by the US Executive Schedule — a document that regulates salaries in the Executive Branch. But where did this document come from? It’s obviously a consequence of politics. But what causes the politics? You see where this thinking goes. As I bemoaned in Rethinking Causation in the Social Sciences, the farther down the rabbit hole of causation we go, the messier things get.

Having admitted this messiness, it’s important to celebrate small victories. Neoclassical economists claim that productivity mediates the returns to education. But at least in one institution — the US military — we can be quite sure that this is wrong. In terms of first-order causation, returns to education in the US military are mediated almost completely by hierarchical rank.