Supply and Demand Deconstructed

July 9, 2021

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

Prices are caused by supply and demand, right? So say neoclassical economists. If you’ve bought their fairy tale, I recommend you watch the video below. In it, Jonathan Nitzan demolishes the neoclassical theory of prices. It’s a master lesson in how to deconstruct a theory.

Here’s the 100-word summary. Nitzan shows that the neoclassical theory of prices fails in six ways:

-

Neoclassical theory hinges on utility that cannot be measured

-

It relies on demand and supply curves that cannot be observed

-

It depends on equilibrium whose existence it cannot confirm

-

It requires but cannot show that demand and supply are mutually independent

-

It requires but cannot demonstrate that the market demand curve slopes downward

-

And it must but cannot measure capital and therefore cannot draw the supply curve, even on paper

So what explains prices?

If neoclassical theory is bunk, then what explains prices? Jonathan Nitzan, together with Shimshon Bichler, argues that prices are inseparable from power.

Here’s a window into Nitzan and Bichler’s thinking. Start with what economists call ‘demand’. If you’re going to buy something you must need or want it. But your want isn’t some fixed property of human nature. It’s a product of your social environment. Want can be massaged, even manufactured. That’s why we have advertising. Everyday, corporations shape our wants so that we buy what they’re selling. This means that demand isn’t some function of autonomous ‘preferences’ (as neoclassical economists would have us believe). Demand is actively shaped by corporate power.

Now let’s look at ‘supply’. It makes sense that if people want something that is scarce, they’ll bid up the price. The problem, though, is that scarcity isn’t just a fact of nature. It’s also an outcome of property rights.

Diamonds, for instance, are a scarce form of carbon. But by itself this scarcity doesn’t explain the price of diamonds. In fact, a primary concern of diamond companies (like De Beers) is that there are too many diamonds. In his seminal PhD thesis, D.T. Cochrane showed that throughout the 20th century, De Beers actively hoarded diamonds to prop up the price. The supply of diamonds was therefore a function power — the power of De Beers to take diamonds off the market.

Administered prices

In capitalist economies, most prices aren’t set by the free market. Instead, prices are administered. They’re set by a manager and then administered to the consumer.

When you stop to think about it, administered pricing is everywhere. Imagine, for instance, walking into Walmart and trying to negotiate prices with the cashier. No one tries to do this because we know it’s foolish. The cashier is powerless to change prices, just as you are powerless to negotiate with Walmart. The reality is that Walmart administers prices to the consumer. So if you want what Walmart is selling, you either pay the listed price or you walk away empty handed.

What’s surprising is not that administered prices exist. Given the power of modern corporations, it would be surprising if prices were not administered. No, what’s surprising is that we’ve known about administered pricing for nearly a century, and yet neoclassical economists still pretend it doesn’t exist. In any other discipline this neglect would be scandalous. But in economics, it’s par for the course. Ignoring contradictory evidence is the tried and true method for maintaining neoclassical dogma.

Let’s have a quick look at this evidence. In the depths of the Great Depression, the economist Gardiner Means was struggling to understand why production had collapsed. According to neoclassical theory, this collapse shouldn’t have happened. Instead, a drop in demand should have been met by a drop in prices. Once supply and demand reached equilibrium, production should have continued unaltered. (Everyone would earn less money, but everything would also cost less. So in ‘real’ terms, nothing would change.) But despite what neoclassical theory predicted, the US was mired in a depression. Why?

To answer this question, Means turned to the evidence. Looking at the relation between prices and production, he discovered something interesting. In some sectors, prices behaved the way neoclassical theory predicted. Faced with the collapse of consumer spending, firms lowered prices and kept production constant. This was exactly what happened in US agriculture (Figure 1). As the Great Depression hit, agriculture prices collapsed. But production remained virtually unchanged.

If all sectors had behaved like US agriculture, there would have been no Great Depression. But not all sectors behaved this way. In fact, some sectors did exactly what neoclassical theory said they should not do: they kept prices constant and slashed production. Looking at the agricultural implements sector, Means found that when the Great Depression hit, prices hardly changed. Instead, production collapsed (Figure 2).

What explained this behavior? The answer, Means surmised, was that firms in the agriculture implements sector had the power to administer prices. This power meant that when consumer spending collapsed, these firms didn’t cut prices. They cut production. Here’s the take-home message. Gardiner Means discovered that the Great Depression didn’t happen in all sectors of the economy. It happened primarily in sectors with administered pricing.

Means’ work remains a master lesson in how economics should be done. To understand prices (and their relation to production), Means looked at the real world. Sadly, neoclassical economists do the opposite. They proclaim that prices are set by the free market. Then they shrug off contradictory evidence (like Means’) as an ‘exogenous shock’. To paraphrase an old saying, history becomes ‘one damned exogenous shock after another’.1

Administered inflation

Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler have continued Gardiner Means’ tradition of studying prices as they are, not as they are imagined (by neoclassical theory). Here’s one of Nitzan and Bichler’s seminal discoveries. Inflation, they find, is largely administered.

On the face of it, this result seems unsurprising. That’s because inflation is usually framed in terms of printing too much money. Since governments control the money printing press, inflation is portrayed as being administered by governments. But this is misleading.

What’s missing from this mainstream description is that inflation is only indirectly about the supply of money. Inflation is directly about the rise of prices. So to understand inflation, you first need to understand how firms set their prices. If prices are administered, it follows that so is inflation. In other words, inflation is created not by printing too much money, but by large firms raising (administered) prices. If this is true, it turns neoclassical theory on its head.

Looking at the evidence, Nitzan and Bichler find that inflation is likely driven by large firms. Figure 3 tells the story. Here Nitzan and Bichler compare the wholesale price index (in the US) to the differential markup of Fortune 500 companies. If you’re not sure what these series mean, I’ll explain shortly. For now, just note that they’re tightly correlated.

Let’s unpack what’s going on. The ‘wholesale price index’ is a measure of inflation. In Figure 3, Nitzan and Bichler plot the rate of change of this index, which indicates how fast prices are rising — the rate of inflation. Nitzan and Bichler then compare this measure of inflation to a measure of profitability known as the ‘markup’. A firm’s markup is its net profit divided by its sales. In Figure 3, Nitzan and Bichler measure the markup of Fortune 500 firms relative to the markup of the whole business sector. They call this the ‘differential markup’.

Fortune 500 firms have markup that is, on average, about 50% greater than other (smaller) firms. This fact is interesting in its own right. But even more interesting is the fluctuation in this differential markup. It moves in lockstep with inflation. In other words, the faster prices rise, the larger the differential markup of Fortune 500 firms. What this means, presumably, is that large firms are able to raise prices faster than small firms. But this implies something shocking: large firms are effectively administering inflation!

Proponents of modern monetary theory (MMT) should take note of this evidence. MMT argues that federal governments don’t have fiscal constraints because they can create their own money. This means that if there is a political will, governments can always finance social spending. A common retort (by MMT opponents) is that printing money will drive inflation. To avoid this specter, governments should balance their budgets (by practicing austerity). Nitzan and Bichler’s evidence provides a strong rebuttal to this argument. Inflation isn’t driven by the government printing press. It’s driven, the evidence suggests, by the pricing practices of large firms. So if you want to avoid inflation, simply regulate prices!

Here’s the take-away message. When we abandon the fairy tale of neoclassical theory, interesting things happen. We start to understand how the world actually works.

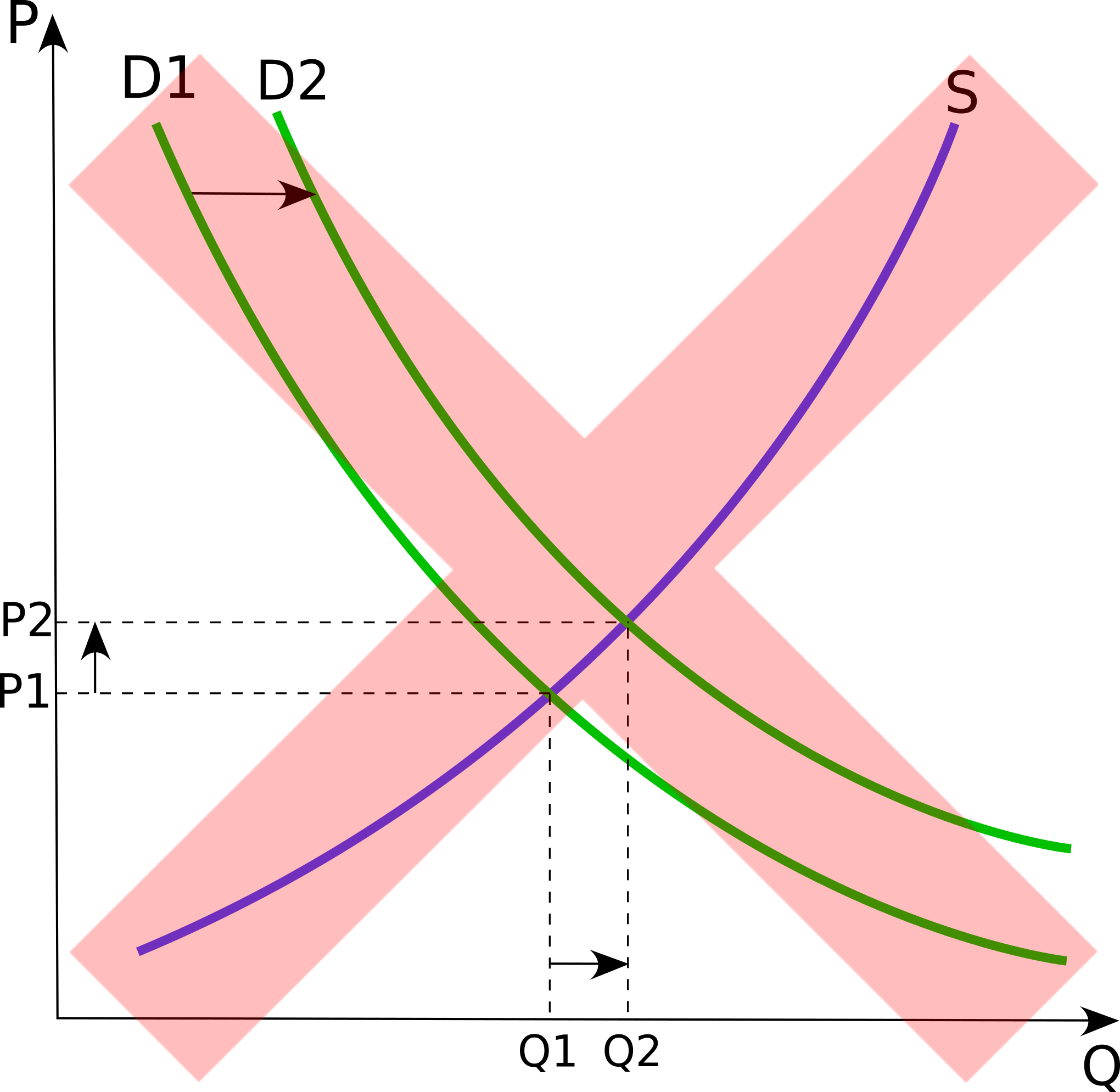

[The cover image is inspired by Steve Keen, who recently told me that in his microeconomics course, he introduces supply and demand curves with a pirate map — as in ‘x marks the spot’.]

Notes

-

The story of how economists ignored and misrepresented Gardiner Means’ evidence for administrated pricing is fascinating. In her aptly-titled essay Academic Resistance to Administered Prices, Caroline Ware recounts the tale:

The most vigorous and persistent attacks [on Means] came from Professor George Stigler of the University of Chicago. In the 1960s Stigler and his associates undertook to study the prices actually paid for items listed in the BLS Wholesale Price Index, presuming that the practice of discounts and other price concessions might result in quite different prices from those reported to the BLS. Their results showed various patterns among concentrated industries, including some price increases in the face of falling demand of the inflationary sort noted by Means. In the text Stigler concluded that this new evidence “destroys the administered price thesis.” But when Means analyzed the Stigler data, he came to the directly opposite conclusion and set forth his interpretation of Stigler’s material in the American Economic Review under the title “The Administered Price Thesis Reconfirmed.” Stigler replied with an article in the same journal, “Industrial Prices as Administered by Dr. Means,” but when Means submitted a rejoinder alleging no less than seventeen errors of fact or in the interpretation of his position, the Review refused publication. Since the Review is the official journal of the American Economic Association, Means appealed to the executive committee of the association, but the latter left the matter in the hands of the editor who indicated that he felt no obligation to keep the controversy alive.

Despite the ample evidence for administrative prices, Ware concludes, most economists continued to use neoclassical theory:

… the main body of economists disregarded the presence of administered prices. Most economists were preoccupied with model building, econometrics, and related theory based on traditional assumptions about price behavior.

(ibid)These words were written in 1992. Nearly thirty years later, they still hold true.↩

Further reading

Cochrane, D. T. (2015). What’s love got to do with it? Diamonds and the accumulation of De Beers, 1935-55.

Keen, S. (2001). Debunking economics: The naked emperor of the social sciences. New York: Zed Books.

Means, G. C. (1935). Price inflexibility and the requirements of a stabilizing monetary policy. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 30(190), 401–413.

Means, G. C. (1992). The heterodox economics of Gardiner C. Means: A collection (F. Lee & W. Samuels, Eds.). ME Sharpe.

Nitzan, J. (1992). Inflation as restructuring. a theoretical and empirical account of the US experience (PhD thesis). McGill University.

Nitzan, J., & Bichler, S. (2009). Capital as power: A study of order and creorder. New York: Routledge.