Why should we teach the history of political-economic thought?

August 25, 2021

Originally published at sbhager.com

Sandy Brian Hager

With the academic term winding down, I thought it would be useful to post some reflections on my teaching experiences this past year. In total, I taught three courses. Two of these courses were inherited from previous lecturers: a second-year undergraduate course on the history of political-economic thought, as well as a Master’s course in theories of international political economy. The third course was a third-year undergraduate course on global inequality, which I designed from scratch.

In many ways, the second year course was the most challenging to design and deliver. The course surveys the great thinkers in political economy starting with Marx and ending with Hayek (with Weber, Veblen, Berle & Means, Keynes, Schumpeter, and Polanyi in between). Specifically, the course focuses in on the views that these major figures in political economy had on the nature of capitalism. How do we motivate students to study capitalism? And how to we motivate the importance of examining specifically what a bunch of dead white guys have to say about capitalism?

I think the answer to the first question is fairly simple. For better or for worse, we live in a capitalist society, one that just recently experienced a very major crisis. And so if we want to understand the world in which we live, we should make a serious effort to study the system that rules our world. Ever since the global financial crisis that started in 2007/2008, there’s been renewed interest in capitalism. And this interest isn’t just academic. In fact, it’s difficult to open a newspaper or turn on a news program and not hear anything about capitalism. And thanks in part to politicians like Bernie Sanders in the US or Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, debates about capitalism have now entered into popular discourse.

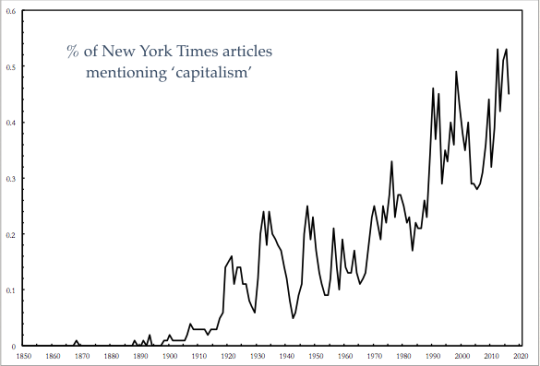

For the introductory lecture of the course, I made a very rudimentary attempt to quantify this growing interest in capitalism, using the (now-defuct) New York Times Chronicle. The Chronicle allowed users to search for certain words to see how often they appear within the New York Times.

In this chart, I’ve searched for the percentage of articles per year published in the New York Times that mention the term capitalism, from 1871 to 2016. In the grand scheme of things, the percentage of articles mentioning capitalism is pretty small. But what we clearly see is that talk of capitalism has been growing more popular. In the late nineteenth century there was almost no talk of capitalism. Then references to capitalism grew steadily during the twentieth century. What’s interesting is that these references started to decline in the early 2000s. But now since the financial crisis, there’s been renewed interest in the topic. So I hope the reason for studying capitalism is straightforward enough.

But what about the second issue? Why should students be concerned specifically with what these dead guys had to say about capitalism? Whether we like it or not, these men have set the terms of debate. They represent the so-called canon of thought. And so whether we agree with their ideas or not, we still need to engage with them, at least as a starting point. And this is what we’ve seen happen since the beginning of the crisis.

In any crisis, people do a lot of soul searching, and oftentimes they look to the past for answers. And during this crisis, there has been renewed interested in the ideas of these old thinkers, especially with someone like Marx. For the introductory lecture, I made this article in the Financial Times required reading and I included the screenshot of the article for the slides. The accompanying cartoon shows the so-called big four within political economy: three of whom we study on the course. Paul Kennedy’s article implores readers of the FT to read Marx, Keynes, Schumpeter, along with Adam Smith (who’s covered in an first-year political economy module at City), in order to truly understand the causes and consequences of the crisis.

This article is just one of the thousands of articles in major newspapers that discuss and debate the ideas of the main thinkers dealt with on the module. So I tell students that if they want to have an informed opinion on these discussions and debates, then it’s inevitable that they’re going to have to familiarize themselves with these thinkers;

I conclude the lecture with a famous quote from John Maynard Keynes in the General Theory (1936: 383), which elegantly sums up the importance of studying the great thinkers in political economy:

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.

The whole message here is that economic ideas are incredibly powerful — they rule our society. Of course everyone wants to be original, we all want to think for ourselves. And no one wants to be a slave to someone else’s way of thinking. But in order to determine whether we actually are slaves to some dead economist’s way of thinking, then we first have to know what these economists actually said. And so I hope that this provides students with a great incentive to take the course.