A Second Look at Hierarchy

October 7, 2021

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

Last fall, I wrote a short article for The Mint Magazine about how income relates to hierarchy. The Mint, if you’re not familiar, does great work promoting pluralist thinking in economics. Check out their on-going Festival for Change — a festival devoted to building a better economy.

Back to my aricle. I submitted a manuscript called ‘A Second Look at Hierarchy’. It got published in The Mint as Down to Size.

Here’s my original manuscript.

✹ ✹ ✹

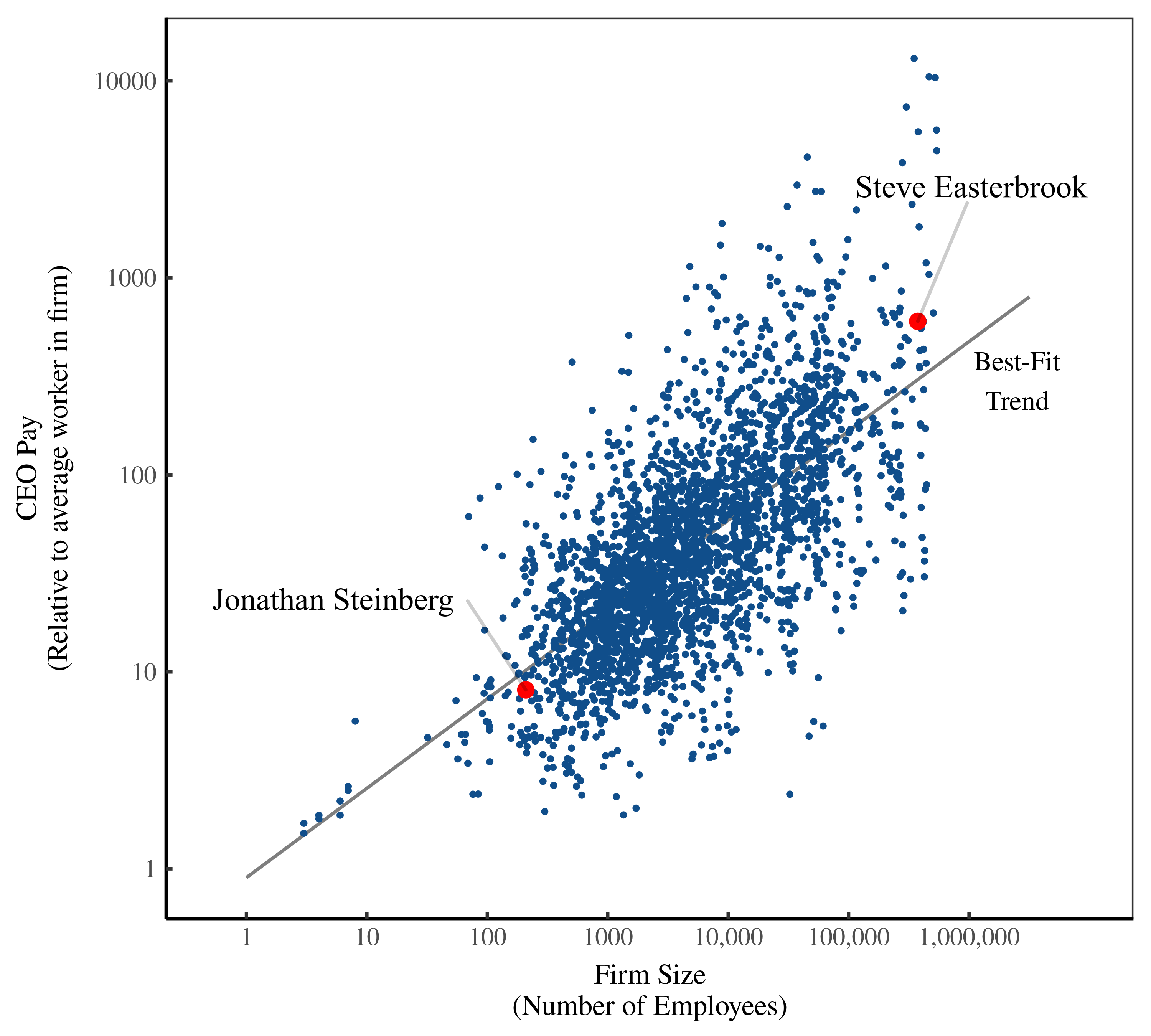

In 2016, Steve Easterbrook had a good year. Easterbrook — a CEO of an American firm — earned about 600 times the pay of the average worker in his company. In the same year, Jonathan Steinberg wasn’t so lucky. Steinberg — another American CEO — earned just 8 times the pay of the average worker in his firm.

Why did Easterbrook earn so much more than Steinberg?

The reason, it turns out, owes mainly to company size. Easterbrook helmed a multinational corporation with some 375,000 employees. Steinberg, in contrast, helmed a small firm with about 200 employees. Although neither Easterbrook nor Steinberg likely knew it, each man’s pay was part of a broader trend. The relative income of CEOs, it seems, grows reliably with firm size.

Figure 1 shows this trend. Each dot represents an American CEO (observed between 2006 and 2016). The vertical axis shows the pay of each CEO, measured relative to the average worker in their firm. The horizontal axis shows the number of employees in each firm. From this data, you can see that CEO pay tends to grow with firm size. You can also see that Easterbrook and Steinberg lie close to the best-fit trend.

This trend raises an interesting possibility. Both Easterbrook and Steinberg likely had preconceptions about their income — that it stemmed, for instance, from things like performance, skill or education. And yet knowing none of these things, an unassuming scientist could have predicted Easterbrook’s and Steinberg’s relative income. The scientist need know only one thing: the size of each man’s firm.

(Steve Easterbrook, by the way, was the CEO of McDonald’s. Jonathan Steinberg was the CEO of a small firm called Wisdomtree Investments.)

A road not taken

If you’re surprised that CEO pay grows with firm size, you’re not alone. Few people know about this trend. And yet it’s not a new finding. The economist David Roberts discovered it in 1956. In the years that followed, other correlates of income (like education) became well known. But the fact that CEO pay grows with firm size remained obscure. Why?

The answer has to do with the road taken by economics.

In the late 1950s (when Roberts published his CEO findings), economists were putting the finishing touches on their theory of income distribution. The roots of this theory dated to the turn of the 20th century. At the time, John Bates Clark had argued that in a competitive market, people earn what they produce. This idea became known as the ‘marginal productivity’ theory of income.

In its initial form, marginal productivity theory applied only to groups of people (capitalists and workers). It left individual income unexplained. For 50 years, this problem went unaddressed. Then, in 1958, Jacob Mincer found a solution. He argued that every individual had something called ‘human capital’ — a stock of skills and knowledge. This human capital explained individuals’ productivity, And productivity, in turn, explained income.

Mincer’s ideas spread like wildfire. Soon most economists proclaimed ‘human capital’ a core part of marginal productivity theory. With their newly-minted theory in hand, economists argued that everyone’s income stemmed from productivity.

It was in these heady days that Roberts published his CEO findings. His results, not surprisingly, were mostly ignored. Why? Because they were hard to square with marginal productivity theory. (Roberts himself tried to attribute executive pay to productivity, but his reasoning was torturous.)

While not easily attributable to productivity, the growth of CEO pay with firm size did have a simple explanation. It was the polymath Herbert Simon who first hit upon it. CEO pay increased with firm size, Simon argued, because of hierarchy.

Here’s his reasoning.

Firms, Simon proposed, are organized using a hierarchical chain of command. The CEO commands a handful of subordinates. And these subordinates, in turn, command their own subordinates. This chain of command creates a pyramid structure, with many people at the bottom of the hierarchy and few at the top.

On its own, this pyramid says nothing about income. But with one simple assumption, Simon made a startling prediction. If income grows with hierarchical rank, CEO pay will increase with firm size. This is because larger firms have more hierarchical ranks. So the CEO of a large firm has a greater rank — and hence greater income — than the CEO of a small firm. Thus, CEO pay grows with firm size.

Simon published this result in 1957. While the paper had an unassuming name (he called it The Compensation of Executives), it dropped a bomb on economic theory. Income, Simon’s model claimed, didn’t stem from productivity. Instead, it was largely a function of hierarchical rank. But because Simon was more mathematician than social radical, he couched this bomb in opaque language. Here’s how he put it:

[O]nly an improbable coincidence would bring about equality between salaries determined by the mechanism described here [pay based on hierarchical rank] and salaries determined by the marginal productivity mechanism.

[Translation: this model conflicts with marginal productivity theory.]

Was Simon correct? Is income within firms largely a function not of productivity, but of hierarchical rank? Unfortunately, it’s difficult to say. Now, as in Simon’s day, we have little data about hierarchy.

Although Simon’s paper opened a new road for economic theory, economists chose not to explore it. Instead, they stayed on the trodden path of attributing income to productivity. In the years after Simon’s paper was published, economists rushed to accept human capital theory. The possibility that hierarchy affected income was ignored.

Here’s an example of this blinder. Gregory Mankiw’s textbook Principles of Microeconomics mentions ‘human capital’ 27 times. It mentions ‘productivity’ (and its derivatives) 74 times. Hierarchy is not mentioned once.

Revisiting hierarchy

As a graduate student, I stumbled onto the evidence shown in Figure 1. The relative pay of CEOs, I found, grew with firm size. Thinking this was a new discovery, I set out to explain it.

Imagine my surprise when I found Simon’s 1957 paper. My ‘discovery’ was not new. It had been first documented 25 years before I was born! What’s more, my ‘discovery’ had an incendiary interpretation that had long been forgotten. The CEO evidence suggested that income within firms was largely a function of hierarchical rank.

Intrigued by this abandoned road of economic theory, I searched for data on hierarchy. To my dismay, little existed. In the 60 years since Simon’s paper had been published, few economists had bothered to study hierarchy. After a year of searching, I eventually found a handful of studies that measured hierarchy within firms. While sparse, this case-study evidence suggested that Simon was on the right track.

To make sense of the evidence, we’ll first generalize Simon’s model. Simon argued that because firms are hierarchically organized, CEO pay grows with firm size. If he was correct, something similar should hold not just for CEOs, but for all employees within the firm.

To generalize Simon’s model, we’ll reflect on what firm size means in the context of a hierarchy. As corporate leaders, CEOs command everyone else in the firm. So the size of the firm indicates (roughly) the number of subordinates below the CEO. The CEO of a 10-employee firm, for instance, has 9 subordinates. And the CEO of a 100-employee firm has 99 subordinates.

Using this insight, we can reinterpret the CEO evidence in Figure 1. It suggests that CEO income grows with the number of subordinates they control. If Simon’s model is correct, the same pattern should hold for all members of the firm. Income should grow with the number of subordinates.

So does income behave this way? The evidence suggests that it does. In the existing case-studies of firm hierarchy, relative income grows with the number of subordinates. Figure 2 shows the trend.

CEOs: superhumans or despots?

It’s time, I believe, to revisit the road opened by Simon’s model of hierarchy. What’s at stake is both the scientific understanding of income and the justification (or lack thereof) for mitigating inequality.

To see why our theory of income matters, let’s revisit our friend Steve Easterbrook. As CEO of McDonald’s, Easterbrook earned 600 times more than the average worker. If mainstream theory is correct, Easterbrook earned this windfall because he was superhuman. He was 600 times more productive than the average McDonald’s employee. If true, most of us would agree that Easterbrook’s income was fair. So there’s no reason to give part of it to someone else.

Now consider the alternative. What if Easterbrook’s income stemmed not from his productivity, but from his command of subordinates? If true, Easterbrook wasn’t superhuman. He was a despot. Much like the kings of old, Easterbrook used his power to enrich himself. So we have every reason to take part of his fortune and give it to the needy.

As you can see, theory matters. Because the stakes are high, I think it’s worth taking a second look at hierarchy.

Further reading

Fix, B. (2019). Personal income and hierarchical power. Journal of Economic Issues, 53(4), 928–945.

Mincer, J. (1958). Investment in human capital and personal income distribution. The Journal of Political Economy, 66(4), 281–302.

Roberts, D. R. (1956). A general theory of executive compensation based on statistically tested propositions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(2), 270–294.

Simon, H. A. (1957). The compensation of executives. Sociometry, 20(1), 32–35.