Google’s monopoly rigged the ad market

March 22, 2022

Originally published at pluralistic.net

Cory Doctorow

The quest to bring antitrust law to bear against tech companies is finally paying off, but it’s been a long, hard slog. At the vanguard have been two legal scholars: Columbia law’s Lina M Khan linamkhan and Yale’s Dina Srinivasan.

The first watershed moment was Khan’s Jan 2017 Yale Law Review paper “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” which laid the groundwork for understanding the inadequacies of Ronald-Reagan-style antitrust for tackling platform capitalism.

https://www.yalelawjournal.org/note/amazons-antitrust-paradox

In Sep 2018, Srinivasan went one better with her Berkeley Business Law Review paper “The Antitrust Case Against Facebook,” which made a compelling case that even under the narrow antitrust Reagan created, Facebook was still an illegal monopolist.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3247362

I’ve just read Srinivasan’s followup, a preprint of a forthcoming Stanford Law Review paper called “Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets.”

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3500919

It was first made available last Jun, before the DoJ announced its antitrust case against Google, and if the DoJ didn’t rely on it to frame its case, there’s a hell of a coincidence at play (even Google’s countermoves since could be ripped from its pages).

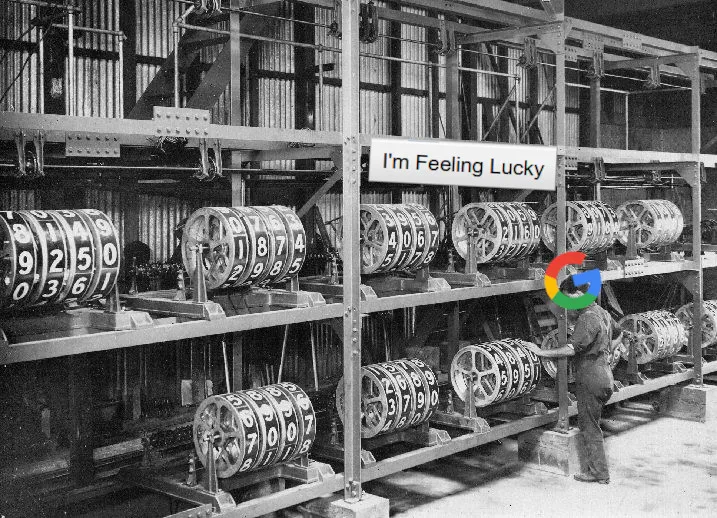

Srinivasan’s paper is a very deep, technological dive into the way that Google has structured the ad-auction market that it dominates. This automated marketplace was based on the computerized stock exchanges that supplanted trading floors, but its volume outstrips all of these.

And yet for all that scale, Google’s marketplace has none of the safeguards that financial markets employ to prevent the market owner from cheating buyers and sellers.

Indeed, even when compared to other online marketplaces, Google is especially bad, continuing practices that other serial offenders like Amazon abandoned as too nakedly anticompetitive.

Marketplaces like the realtime ad-placement system are complex, involving publishers, advertisers, sell-side brokers, buy-side brokers, and the markets where they come together. Google manages to insert itself into nearly every element of the system.

When you see an ad on a website, it is often the case that Google brokered both the advertiser’s bid and the publisher’s acceptance, in a marketplace that Google controls, and (through AMP), Google may even host the page with the ad on it.

Srinivasan documents how Google has muscled out competing brokerages, exchanges and hosting systems by citing benefits to internet users: privacy measures had the (surely not incidental) side-effect of making it impossible for rivals to target as well as Google does.

Measures aimed at improving load times (AMP again) forced publishers to choose between giving up 50% of their ad revenue or giving up on being visible in Google search results.

And all of this has the (again, not coincidental) side-effect of giving Google access to proprietary business information that lets it compete with, squeeze, and sideline publishers.

All of this points to the foolishness of “link taxes” – proposals in the EU, Australia and Canada to make Google pay for the right to link to news sites (and to find a way to force Google to go on linking to those sites rather than not paying the tax).

Srinivasan makes a really compelling case that Google’s multiple conflicts-of-interest – sell-broker, buy-broker, exchange operator, host and search tool – has shifted huge amounts of money from publishers to the company.

But she also demonstrates that when there is competition (for example, when publishers were briefly able to solicit ad bids on multiple simultaneous exchanges), publishers can double their revenues (and advertisers can lower their ad costs).

All this suggests that the answer to Google isn’t to force it to provide charitable payments to the press that is supposed to be reporting on it and holding it to account – but rather to force Google to halt their anticompetitive conduct.

If we did that, Google couldn’t afford to float the news media – but that would be because the news media had shifted a giant share of ad revenue from Google to itself. Publishers wouldn’t need Google’s charity – they’d have its revenues, instead.

Recall that the reason Google (and other tech giants) have been able to dominate our digital world is that Reagan neutered antitrust law, allowing companies to form brutal, all-encompassing monopolies without fear of state action.

The DoJ’s antitrust action against Google suggests that we may be able to restore the more muscular, trustbusting version of competition law, but Srinivasan’s not waiting for that to happen.

Instead, she closes her paper by reminding us that Google’s ad-market was explicitly based on stock markets, and that these markets have a well-developed set of regulations to prevent the self-dealing that accounts for most of Google’s profits.

While we’re waiting for antitrust to reinvent itself, Srinivasan suggests that we subject the ad market to financial laws. Doing so wouldn’t just address Google’s abuses: whole swathes of our economy are disappearing into these algorithmic marketplaces (like Ticketmaster’s).

Srinivasan suggests that all of these markets should be regulated to prevent the exchange operator from cheating the buyers and sellers.

It’s a very interesting idea – and the paper is beautifully written and argued.

I have two reservations, though:

I. The financialization of other sectors of the economy is Not Good. Rather than reforming Ticketmaster’s abusive marketplace (or Google’s), why not prohibit it? I don’t want “fair” financialization, I want no financialization.

II. Google’s moves – third-party cookie blocking, bans on merging user identifiers, downranking sites with lengthy “surveillance lags” generated by complex ad bids – really are good for users. I’d love to find proposals to fix this stuff without creating monopolies.