The Story of Machines vs. Labour

July 8, 2014

DT Cochrane

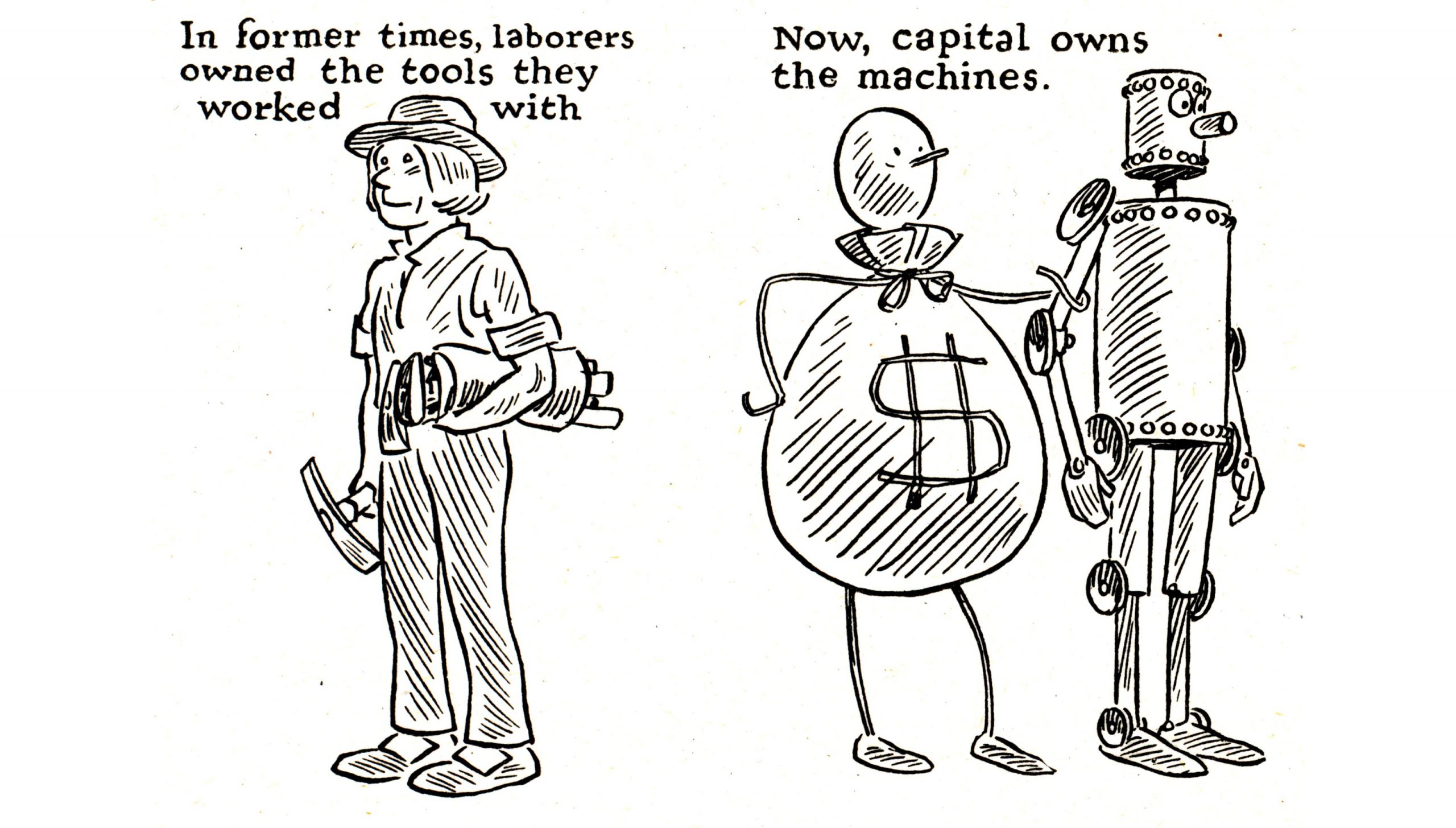

The replacement of labour by machines has brought many improvements in social well-being. New machines have made a wide variety jobs safer and less physically debilitating. Yet, the process is far from decisively good, with many attendant ills. Consider the mechanization of fishing boats. Fishing is a dangerous activity and having fewer workers on the ships puts fewer lives at risk. However, the loss of the fisheries jobs has decimated maritime communities. The introduction of new technologies transforms communities, the goods and ills of which are indeterminate and continually evolving.

The story is an on-going one. Consider recent suggestions that new software could make half the world’s jobs disappear. These new displacements are occurring in jobs previously considered safe from mechanization, like legal research or grading papers. We continue to be simultaneously horrified and fascinated by how new machines and the tasks they can perform, have effectively rendered redundant the humans who used to perform those tasks.

Political economic understanding of the substitution of machines for labour is based on the value theory we adopt. Marx was not ethically opposed to the substitution of machines for labour, even if the system of machinery was implicated in the alienation of the worker. He criticized the Luddites, who broke the machines that were displacing workers, for standing in the way of progress. Although Marx deplored the conditions of work faced by the labouring class, he also saw the machines as, ultimately, a force for good. Importantly, Marx also believed the machines, despite benefiting capitalists in the short-term, doomed capitalism.

Marx’s value theory is a dual-quantity theory. Financial values are the visible representation of real values that are embodied in the social output of production, including the machines that enter into the next round of production. According to Marx’s theory, value could only be created by labour. Machines were a store of ‘dead value,’ and couldn’t actually create value. One of the consequences of increased capital accumulation, according to Marx, was the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

Despite relentless proletarianization – turning ever more people into workers – Marx theorized that total capital would outpace the quantity of labour. Among the consequences of this, he believed, would be the immiseration of the working class, as more surplus is squeezed out, and concentration of ownership increases. Because the profit rate would continually fall, accumulation would eventually come to an end, and thereby the fate of capitalism was foreordained: “The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.”

From the perspective of capital as power (CasP), there is no ‘real value’ distinct from financial values. As such, there is no meaningful aggregate quantity that can be identified as ‘total capital.’ In contrast to dual-quantity value theories, CasP focuses not on absolute accumulation, but on accumulation as a redistributionary process, both between capitalists and the rest of us, and among capitalists themselves. Although Marx recognized that profit rates would differentiate between sectors, he believed it was the aggregate rate that was of ultimate political economic consequence.

According to CasP, capitalists seek not some shared, aggregate accumulation, but rather to beat a moving benchmark. This is because their gains are strictly financial, and what financial values represent are not another quantity, but owners’ relative control over qualitatively diverse social relations. This means there can be victory even in decline, as long as one’s fellow capitalists decline faster.

Much emphasis within CasP is on the intra-capitalist struggle for differential gain as the engine for qualitative upheavals that impact society in myriad indeterminate ways. As such, the scope of political economy is greatly broadened from a focus on arenas of production, distribution and consumption to anything that might be a cause or effect of capitalist activity, as such as racialized poverty, gendered wage disparity, and widespread pollution, as well as mechanization and its consequences.

Although mechanization has important aggregate consequences for labour, and the rest of society, these cannot be understood in the Marxian terms, which require ‘real value’ as a meaningful aggregate. Instead, it will require the development of other measures and tools of analysis, some of which are already being deployed by a wide variety of social scientists. From a political economic perspective, we can consider the aggregate consequences of capital accumulation in relation to the masses, as in the astute sloganeering of the Occupy movement, and as analyzed in Thomas Piketty’s unexpected bestseller on distribution. But, there is no absolute meaning associated with this accumulation, as there is no absolute quantity in which to measure it. As such, political economic analysis of mechanization should be conducted in terms of redistribution and differential interests.

Against Marx, who believed that increased proletarianization was a necessity of capitalism, since only labour produces value, a CasP analysis sees no such necessity. Rather, various capitalists may all choose to substitute machines for workers, as part of a power process — which has been perceptively analysed by Marx-inspired thinkers like David Noble and Stephen Marglin — with increasing unemployment as an aggregate consequence, along with differential value gains by certain segments of capital at the necessary expense of others.

Unfortunately, capitalism can likely survive ever increasing mechanization with its attendant ills for workers. However, both CasP and Marxist analyses seemingly point in the same normative and practical direction: widespread control of the decision-making process over whether or not we ought to mechanize a workplace or industry. Leaving the decision-making to the owners, whose sole concern is accumulatory gain, will not serve the greatest social interest.

Great post!

Here’s a question: how much longer can machines replace workers?

In my view, there are fundamental limits to this process, dictated primarily by energy resources.

All machine require energy for both their construction and operation. Replacing workers with machines requires an increase in energy consumption per labor hour. If energy supplies were infinite, this process could continue indefinitely. However, the vast majority (about 85%) of global energy comes from fossil fuels, and this is unlikely to change any-time soon. Fossil fuels are finite and exhaustible.

The peak in fossil fuel production, in my view, will likely coincide with the maximum extent of machine-worker replacement. After the peak, my prediction is that the trend will reverse.

Blair,

This would assume that we cannot find renewable sources to replace and augment our current power demands.

That said, fossil fuels have definitely played an important role in the process. Energy intensity has always been discounted in our increased productivity in favour of self-congratulatory claims about human ingenuity. If fossil fuel use were not under-priced, as it externalizes costs associated with pollution, then the process would have been much slower and much different.