Living the Good Life … Without Killing the Planet

June 8, 2021

Originally published on Economics from the Top Down

Blair Fix

How can we live the ‘good life’ without killing the planet? My last post on energy and empire got me thinking about this question. We know that human welfare improves as we use more resources. But it’s suicidal for all of humanity to pursue this path. If the whole world lived like Americans, we’d triple our carbon emissions.1 So that’s not an option (not a sane one, at least).

How, then, can we improve human well-being without consuming more resources? Many people have an opinion on this question. But instead of giving you my opinion, I’ll look at the evidence. Let’s see what countries actually do to improve human welfare without using more energy.

Measuring well-being

I’m going to measure well-being using life expectancy (from birth). It may seem like a crude measure, but the more I think about it, life expectancy is probably the best measure of welfare we have. First, people universally want to be healthy. And there’s no better way to measure health than to see how long people live. Second, ‘health’ is holistic — it’s affected by your whole life experience. Health tends to worsen when you’re stressed, unhappy, and otherwise malcontent. I think it’s reasonable, then, to use life expectancy to measure human welfare in a holistic sense.

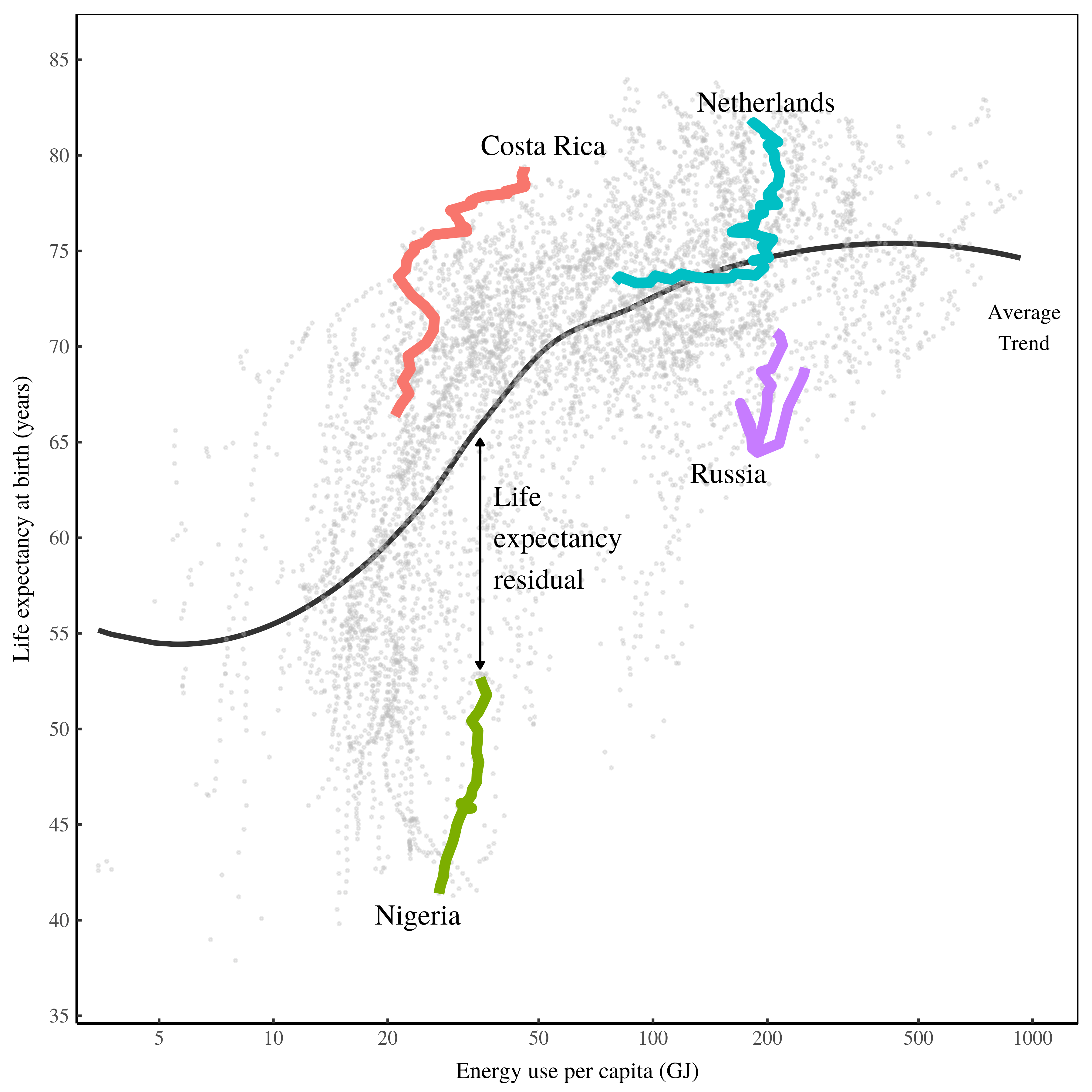

So how can we increase life expectancy? The route we’ve taken for the last two centuries is to consume more energy. Make no mistake, this works. As Figure 1 shows, using more energy (per person) reliably increases life expectancy. The black line is the trend across all the data. Countries that start at agrarian levels of energy use (about 20 GJ per person) can expect to gain, on average, about 20 years of life expectancy as they industrialize.

This life-expectancy gain from using more energy is important. But notice that it’s extremely inefficient. To live 35% longer, we need to consume, on average, 1000% more energy per person. That’s hardly a large return. In fact, energy use accounts for less than half of the variation in life expectancy.2 Clearly there are other ways to improve human welfare that don’t involve consuming more resources.

Figure 2 illustrates this fact. Here I pair countries that have similar energy use. Costa Rica and Nigeria, for instance, both consume about 40 GJ of energy per person (per year). And yet their life expectancies are wildly different. The average Costa Rican can expect to live to 80; the average Nigerian, to barely over 50. At higher energy use, similar differences exist. Russians and Netherlanders both consume roughly 200 GJ of energy per person (per year). Yet on average, Netherlanders live a decade longer than Russians.

Life expectancy residuals

As Figure 2 illustrates, life expectancy is clearly affected by something other than energy. In statistics, we call this unexplained effect a ‘residual’. Visually, the ‘life expectancy residual’ is the vertical distance between the average-trend line in Figure 2, and the life expectancy in a given country. I’ve illustrated the residual for present-day Nigeria. The average Nigerian lives 12 fewer years than expected from the energy-life-expectancy trend. The average Costa Rican, in contrast, lives about 10 years longer than expected from the trend.

These ‘life expectancy residuals’ hold the key for understanding how to improve human well-being without using more resources. To lift the veil on this elixir, we need to explain the residuals.

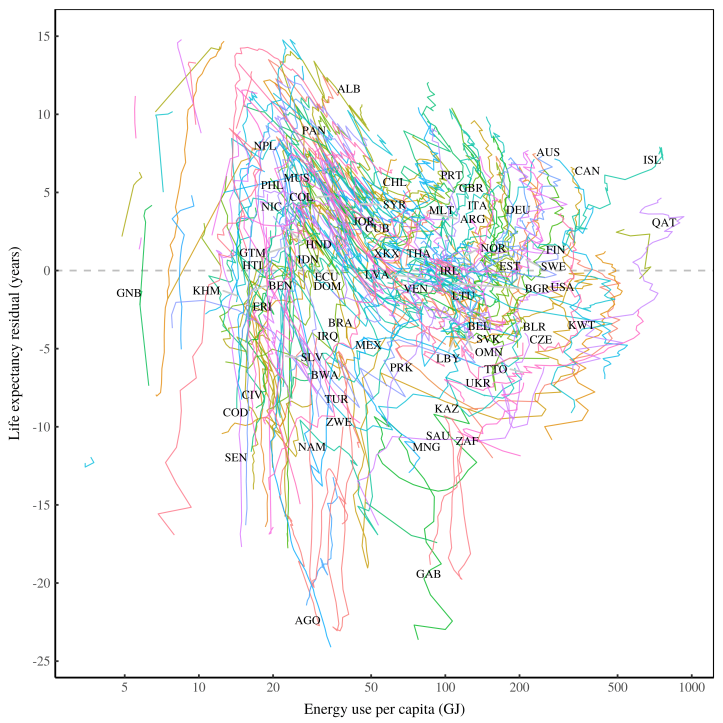

The first step is to calculate the life expectancy residuals for all countries. Figure 3 shows the results. As in the previous figures, the horizontal axis shows energy use per capita. But rather than show life expectancy, the vertical axis now shows the life expectancy residual — the deviation from the average trend. Residents in countries above the dashed horizontal line live longer than expected from the energy-life-expectancy trend. Residents in countries below the dashed line live shorter than expected. Our goal is to explain this blob of data. Why are some countries above the dashed line and others below? What do they do differently?

To understand these life expectancy residuals, we’ll see what they correlate with. Here’s an example. Suppose we have data for the portion of people who smoke tobacco. We’d expect this data to correlate negatively with life expectancy residuals. This means that irrespective of energy use, smoking tends to lower life expectancy. Now suppose that wearing seat belts correlates positively with life expectancy residuals. This means that irrespective of energy use, wearing seat belts tends to increase life expectancy. So to live longer without consuming more energy, we should wear seat belts and not smoke.

Now to real-world data. To understand the energy-life expectancy residuals, I compare them to (almost) every series in the World Bank database.3 If you’re not familiar, the World Bank database is arguably the most comprehensive dataset of human society ever constructed. It contains nearly 7000 different data series that cover virtually all aspects of human life.

I’ll show you here the 10 World Bank metrics that correlate most positively with the energy-life-expectancy residuals. These are things that improve human well-being without using more energy. Then I’ll show you the 10 metrics that correlate most negatively with energy-life-expectancy residuals. These are things that worsen human well-being (without reducing energy use).

How to increase life expectancy without using more energy

Figure 4 shows the 10 World Bank metrics that correlate most positively with energy-life-expectancy residuals. When societies do these ten things, people tend to live longer without consuming more energy.

Let’s walk through the chart. The horizontal axis in Figure 4 shows the correlation between the given metric and energy-life-expectancy residuals. The larger the correlation, the more tightly life expectancy increases with the given metric. The boxplots indicate the variation in the correlation over time. (Here’s how you read a boxplot. The vertical line indicates the median of the data. The ‘box’ indicates the middle 50% of data. And the horizontal line indicates the data range.)

Now to the results. The series that correlates most strongly with energy-life-expectancy residuals is the part time employment rate of females. In fact, the part time employment rate appears three times in Figure 4 — once for females, once for males, and once for the whole population. This result is surprising. Many sociologists see part time work as a bad thing. It usually pays worse than full time work. And part time jobs are more precarious, and often come with fewer health benefits. (See Guy Standing’s book The Precariat for details.) So why does more part time employment correlate with a longer life expectancy?

This result doesn’t make sense … until we unpack the data itself. It turns out that ‘part time employment’ is defined as working less than 35 hours per week. In the United States, that’s certainly ‘part time’. But in other countries it’s not. In Norway, for instance, the average work week is 34.6 hours. So according to the World Bank’s definition, the majority of Norwegians work ‘part time’.4 But it’s not like the Norwegians are suffering. Their benefits are famously luxurious — a minimum of 25 paid vacation days, not to mention universal health care. It’s something the average American can only dream of. So while the data ostensibly measures ‘part time work’, it’s actually measuring (indirectly) the average length of the work week. The results, then, suggest that when the whole population works fewer hours, human well-being benefits.

Let’s move down the list. The second strongest correlation with our life expectancy residuals is primary school enrollment. The more primary-age children who are in school, the longer people tend to live. In some ways, the importance of education is unsurprising. We know that it benefits children. But how does education benefit the whole population? Hold on to this question, because I’ll save my thoughts on it until the end.

Next on our list is the percentage of people with access to electricity. This result is interesting. Electrification of the energy supply generally happens as societies consume more energy. This means there shouldn’t be much of a correlation between access to electricity and our life expectancy residuals. (If electricity access increases tightly with energy use, there’s no ‘electricity residual’ left to correlate with our life expectancy residual.) What I suspect is going on here is that there’s an equity issue at work. Yes, electricity use spreads as energy use increases. But it spreads unevenly. Sometimes there are great gaps within countries. The urban rich consume electricity. The rural poor do not. The evidence tells us that reducing this electrification divide increases life expectancy.

All of the remaining series (except one) in Figure 4 come from the Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA). These are not direct measurements, but rather ‘assessments’ created by the World Bank based on different sets of criteria.5 While we should treat such assessments with uncertainty (there’s inevitable subjectivity involved), the results are still interesting.

Let’s start with property rights and rule-based governance. As this metric increases, so does life expectancy. It’s tempting to focus here on the word ‘property’, but a look at the CPIA methods shows that they’re mostly ranking the ‘rule of law’. It’s actually straightforward to relate this directly to life expectancy. Absent the rule of law, the evidence is pretty clear that human societies become more violent. In pre-state societies, the murder rate is often an order of magnitude higher than in state societies. (See Steven Pinker’s book The Better Angels of Our Nature.) The rule of law may directly increase life expectancy by decreasing violence. The rule of law probably has other indirect effects on human welfare, but these are less straightforward to parse.

Next on the list is equity of public sector resource use. As public sector spending becomes more ‘equitable’, life expectancy increases. This metric ranks governments’ attempts to alleviate inequality, both by measuring poverty and by redistributing income through progressive taxation. No surprises here. We know that inequality is corrosive to human welfare. So making society more equitable makes people live longer. (See The Spirit Level for a discussion of the harmful effects of inequality.)

Next on the list is transparency, accountability, and corruption in the public sector. As transparency and accountability increase, so does life expectancy. This metric measures equity, but this time in terms of control over government. Again, no surprises. If the government is corrupt and oligarchic, it will tend not to care for its citizens. As a result, life expectancy suffers.

Last on our CPIA list is policies for social inclusion/equity. We can think of this metric as a broad ranking of the welfare state. It includes policies for gender equality, social safety nets and investments in education. So improving the welfare state increases life expectancy. That’s unsurprising. Improving human welfare is the raison d’être of the welfare state.

Finally, the 10th metric on our list is manufacture exports as a percentage of merchandise exports. (Here ‘merchandise’ is synonymous with all ‘goods’, meaning everything that is not a service.) What does manufacture exports have to do with life expectancy? I’d guess that it mostly indicates a country’s position within the global economy. Countries that export more manufactured goods are, by extension, exporting fewer natural resources. This plays into the idea of the ‘resource curse’.

In the mid-20th century, economists noticed that many countries that were rich in natural resources tended to have sluggish economic development. Of course, the idea that natural resources themselves could be a curse is absurd. It’s how the resources are exploited that matters. The whole point of having natural resources is not to export them, but to use them yourself. But countries that are on the periphery of the world economy don’t (can’t?) do this. They ship their resources off to other countries. And they suffer for it. Such resource-exporting countries sell natural resources cheap and buy back manufactured goods dear. That’s the opposite of what wealthy countries do. And, it seems, this difference is reflected in life expectancy. (For a good investigation of unequal resource flows in the global economy, see Alf Hornborg’s book Global ecology and unequal exchange.)

How to decrease life expectancy without using less energy

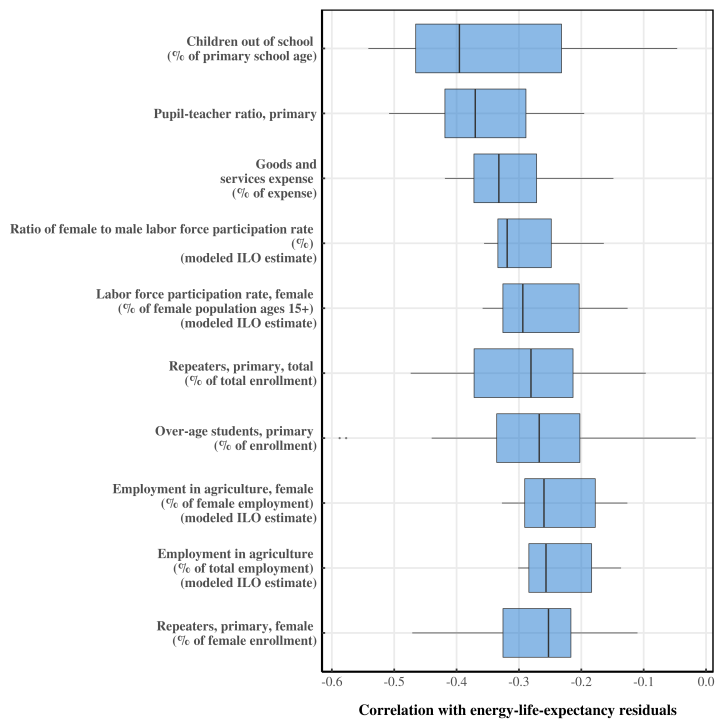

Let’s turn now to the things we don’t want to do to increase human welfare. Figure 5 shows the 10 metrics that are most negatively correlated with energy-life-expectancy residuals. Increase these ten things and people die younger (without using less energy).

Interestingly, lack of education tops the list of ‘bads’. In fact, 5 of our 10 metrics are education related. These include:

-

percentage of primary-age children out of school (more children out of school = lower life expectancy)

-

pupil-teacher ratio in primary school (more students per teacher = lower life expectancy)

-

repeaters in primary school, % of enrollment (more students failing grades = lower life expectancy)

-

over-age students, % of enrollment (more over-age students = lower life expectancy)

-

female repeaters in primary school, % of enrollment (more females failing grades = lower life expectancy)

All of these education indicators are self-evidently bad for children. What is less obvious is that they’re bad for the whole population. When schooling is worse, it seems that everyone dies younger (on average). Why? Hold your thoughts until the end.

Let’s move on to other metrics. The portion of expenses spent on goods and services is third on our list. As with part time employment (in Figure 4), the name of this metric is misleading. It actually measures the portion of government expenses spent on goods and services.6 This is really a measure of the financial health of government. We can see this by looking at the other two major categories of government spending. They are: (1) employee compensation; and (2) social benefits, subsidies and grants. Let’s put it this way: a government that spends most of its money buying office supplies can’t do much for its citizens. It can’t pay its employees well. Nor can it provide services to the population. So when government spending on goods and services increases, life expectancy decreases. That makes sense.

Let’s move down our list again. It seems that life expectancy decreases as more women enter the workforce. Wait … what? This result seems absurd, but I’ll explain why it makes sense in a second. First, let’s define the data. The ratio of female to male labor force participation rate measures the relative number of females in the workforce compared to the relative number of males. Surprisingly, more females (relative to males) tends to worsen life expectancy. The same is true for the labor force participation rate of females. The larger the fraction of females in the workforce, the lower the life expectancy.

This result is surprising because a key goal of the feminist movement is to give women the right to do paid work. Could this movement be harming human welfare? I think the answer is almost certainly no. What’s actually going on here is that female participation in the labor force measures two things:

-

The ability of women to enter the paid workforce.

-

Male withdrawal from the workforce.

These two things likely impact society very differently. It’s almost certainly a good thing for women to have the right to do paid work. Having this right means women work because they want to, not because they have to. But when males withdraw from the workforce, things are very different. Then women do paid work out of necessity.

When men withdraw from the workforce, it’s usually because they can’t find a job. And when unemployed, men generally don’t pick up the tasks that would have been done by women. Instead, they often do nothing. They resort to substance abuse and sometimes even crime. (For a good discussion of what men do when there’s no paid work, see Dmitry Orlov’s book Reinventing Collapse.)

Looking at the data, the countries with the highest female participation in the (paid) labor force are mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. These countries are hardly bastions of feminism. Women here are likely doing paid work because they have to … because men are not. So it seems that when women are forced into the paid labor force (because men have withdrawn), life expectancy suffers.

At the end of our list of metrics is employment in agriculture. For a given level of energy use, life expectancy decreases if more people work in agriculture. This is interesting because agricultural employment is intimately linked to energy use. (Getting people off the land requires using more energy.) Why does having more people in agriculture lower life expectancy? A simple explanation is that health care is usually better in urban areas. If more people work on the land, access to healthcare will be worse, and so life expectancy will be lower.

There is, however, a more subtle reason that having more people in agriculture lowers life expectancy. Put simply, countries don’t need to grow their own food. They can import it instead. This is the strategy of wealthy island states like Singapore. It grows almost no food, and yet enjoys a high standard of living. How? By being a business center. Wealthy countries like Singapore are at the core of the global economy, allowing them to urbanize without growing their own food. Thus they get the benefits of urbanization without the (direct) energy costs of agriculture.

Staving off ignorance

I asked you to hold your thoughts on education until the end. Now let’s discuss it. What leaps off the page in Figures 4 and 5 is the importance of education. When more children are in school, the whole population seems to live longer (Fig. 4). Conversely, when fewer children are in school, (or when school is worsened by decreasing the number of teachers), the whole population dies younger (Fig. 5).

I’m obliged to point out first that we’re dealing here with correlation. We haven’t established that universal schooling causes people to live longer. The fact that it could, though, is important. It’s also a bit counterintuitive.

It’s easy to see how things like healthcare make people live longer. Healthcare directly saves lives. But how would education raise life expectancy? Perhaps education improves the welfare of children, and this benefit carries over into adulthood. This is certainly plausible. But there’s also a more expansive case to be made for the benefits of education. Think about it this way. Humanity is always one generation away from ignorance.

Think about everything that you know — all the facts, skills, and tricks that you use in your job and in your life. Unlike most animals, you were not born with these skills. Instead, you acquired them from the previous generation of humans. And this previous generation acquired their skills and knowledge from the generation before. And so on.

In an important sense, the only thing that separates modern humans from our ancient forebearers is this cumulative transmission of culture. We have at our disposal the skills and knowledge of thousands of previous generations of humans. Destroy our machines and infrastructure and we’ll rebuild them (as after World War II). But block the transmission of culture and we’d be back to the Stone Age.

In the past, cultural transmission was passive, in the sense that it wasn’t planned. But today we have a system of deliberate cultural transmission. We call it education. The point of this system is to transfer to each new generation the cumulative knowledge of all previous generations. The better the education system, the better this cultural transmission.

When you frame education this way, it’s unsurprising that it relates to life expectancy. Literally all of the skills and knowledge that we use to improve human welfare are learned. Block or damage the learning of these skills, and human welfare suffers.

So if we want to improve human well-being without consuming more resources, I think we have a clear path. Invest in education. Invest in passing on (and improving) humanity’s cumulative knowledge.

Sources and methods

All data comes from the World Bank. You can browse the data at data.worldbank.org, or download the whole database here. Energy use per capita data comes from series EG.USE.PCAP.KG.OE. Life expectancy (at birth) is from series SP.DYN.LE00.IN.

I calculate the energy-life-expectancy trend (in Figures 1 and 2) using a locally-weighted polynomial regression. Residuals are then measured as deviations from this regression. For residual analysis, I include only World Bank series that cover at least 50 countries over a period of 20 years or more.

Notes

-

According to worldometer, the United States emits about 15.5 tons of CO2 per person (per year). The world average is 4.79 tons per person. So bringing the rest of the world up to US levels of fossil fuel consumption would roughly triple our carbon emissions↩

-

We can use a simple regression to measure the variation in life expectancy that is ‘explained’ by energy consumption. We assume that life expectancy grows linearly with the log of energy use. For this regression, R2 = 0.44. This indicates that 44% of the variation in life expectancy is ‘explained’ by changes in energy use. I’ve put ‘explained’ in scare quotes because we’re talking about a statistical explanation, not a causal one.↩

-

I discard World Bank series that are directly related to life expectancy — things like death rates and disease rates. I also throw away data about GDP and/or the energy intensity of GDP. I do this because (1) ‘real’ GDP is a flawed metric; and (2) it is strongly correlated with energy use, and hence, material flows. I’m interested here in ways of improving well-being without using more resources.↩

-

Actually, the World Bank is in this case using data from ILOSTAT. So the definition of ‘part time’ technically comes from ILOSTAT, not the World Bank.↩

-

You can read about the Country Policy and Institutional Assessment’s ranking criteria here.↩

-

In this case, the World Bank data comes from the IMF. You can find the government expense criteria in the IMF manual.↩

Further reading

Hornborg, A. (2011). Global ecology and unequal exchange: Fetishism in a zero-sum world. New York, NY: Routledge.

Orlov, D. (2008). Reinventing collapse: The Soviet example and American prospects. New Society Pub.

Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined. New York: Penguin Books.

Standing, G. (2011). The precariat: The new dangerous class. New York: Bloomsbury.

Steinberger, J. K., Lamb, W. F., & Sakai, M. (2020). Your money or your life? The carbon-development paradox. Environmental Research Letters, 15(4), 044016.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. (2009). The spirit level: Why more equal societies almost always do better. New York: Penguin Books.