Problems of the Periphery in Federico and Tena’s World Trade Data

December 8, 2021

Originally published at joefrancis.info

Joe Francis

Giovanni Federico and Antonio Tena-Junguito (2016) have produced a data set of world trade that includes exports and imports, in both current and constant prices, going back to the early nineteenth century for over 100 countries. It will give all economic historians a mass of easily available long-term time series. What could there possibly be to complain about? In short, methodologically speaking, it’s a bit iffy.

In an article published in Historical Methods I showed that any attempt to measure a peripheral country’s terms of trade during the nineteenth century using prices taken from the core countries will have a downward bias in its trend due to the effects of price convergence (Francis 2015). It appears, however, that Federico and Tena may not have read that article.

Federico and Tena’s goal is to produce export and import values in both current and constant values for all the countries in their sample. Their general approach appears to be to find the current values then deflate them using price indices. When possible, those indices are calculated using prices from the countries themselves, but for peripheral countries they more often than not have to construct new indices by taking prices from Britain, then subtracting freight and insurance rates, in order to arrive at estimates of the export price in the country of origin. For that country’s imports, the procedure is done in reverse: freight and insurance are added to British prices.

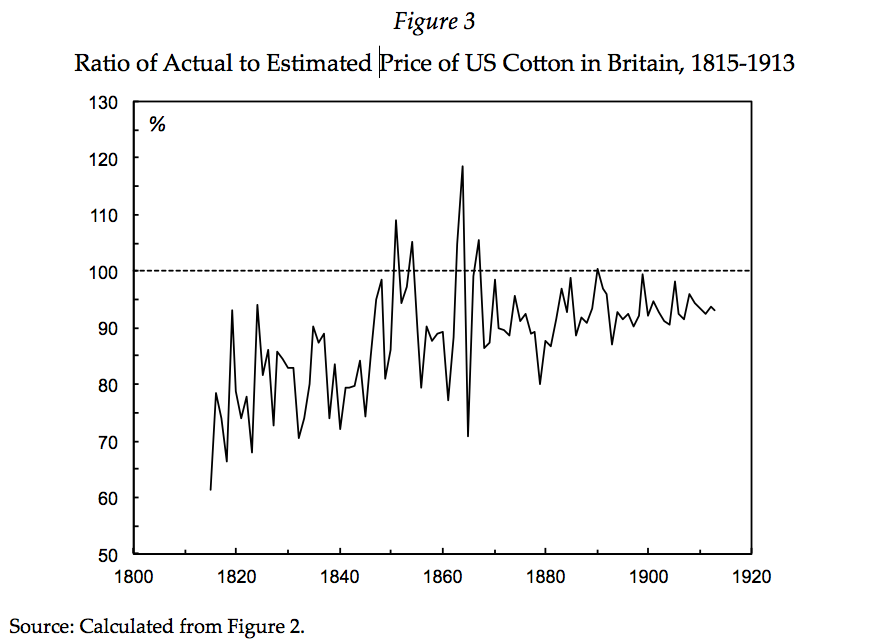

The problem with this methodology is that trade costs included far more than freight and insurance. The clue is in the term ‘cost, insurance, and freight’ (CIF). CIF prices include not only insurance and freight but also other costs, which would need to be subtracted to arrive at ‘free on board’ (FOB) prices or added to FOB prices to arrive at CIF prices. By only subtracting or adding freight and insurance, Federico and Tena ignore the substantial other costs that accounted for the majority of international price differences during the nineteenth century.

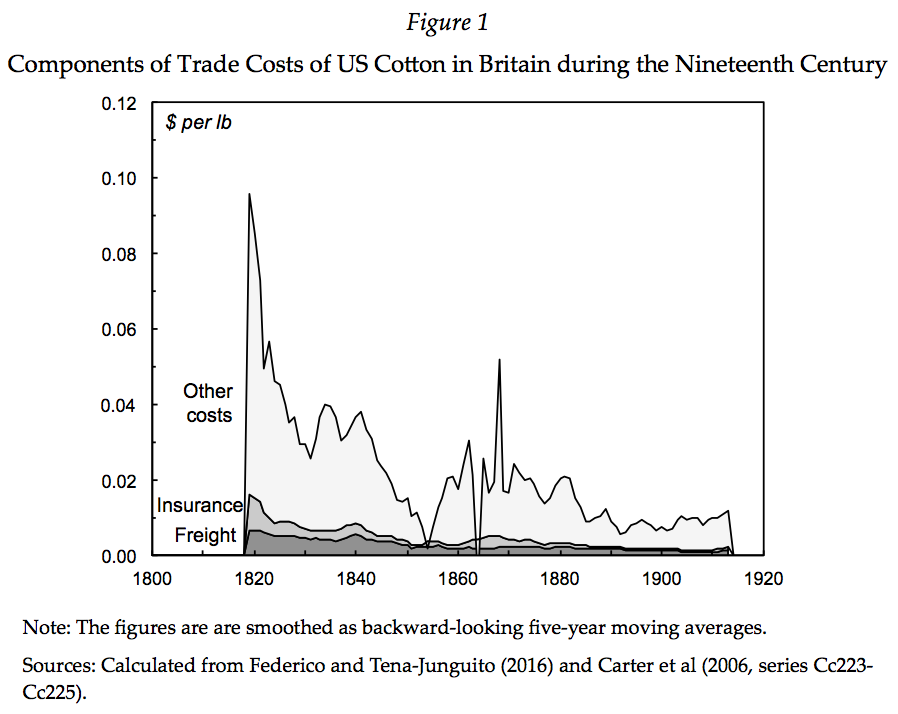

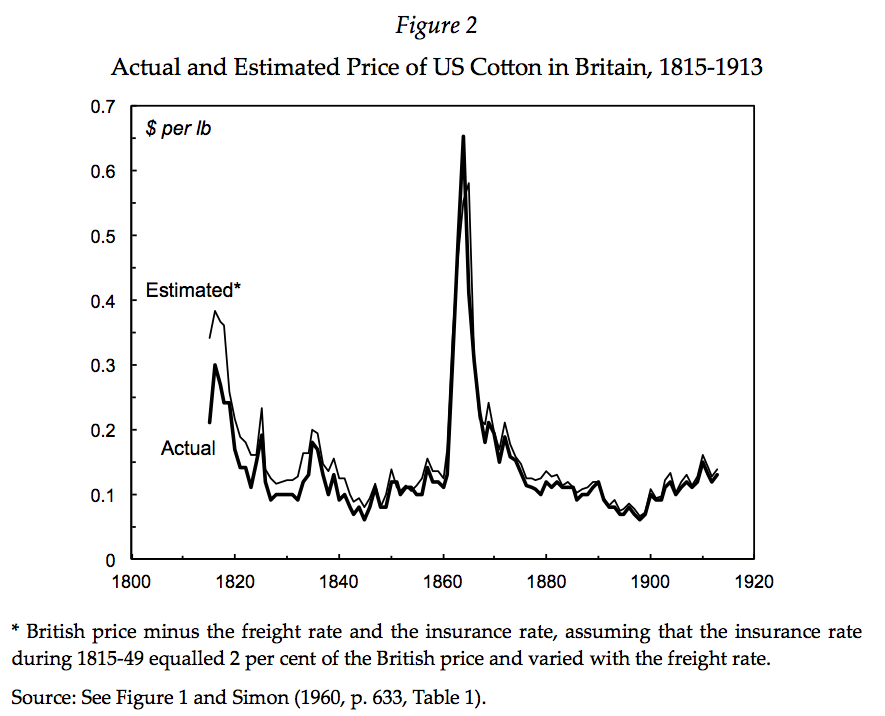

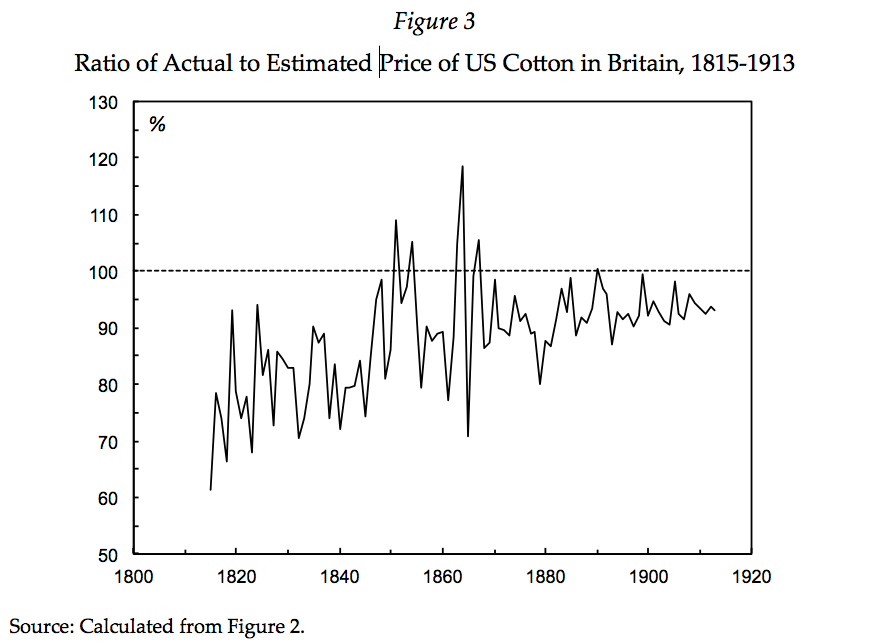

The price of US cotton in Britain illustrates the problem with Federico and Tena’s methodology. Figure 1 shows that in the 1820s US cotton cost 3-8 cents more per pound in Britain than in the United States. Of this difference, around half a cent was due to freight and even less due to insurance. The remainder was due to other costs. Consequently, subtracting freight and insurance from the British price is not enough to arrive at the US price. As shown in Figure 2, the estimated price is substantially too high early in the nineteenth century, although the gap then lowers. This is confirmed by Figure 3, which shows the actual price as a percentage of the estimated price. For the late 1810s, it is around 70 per cent, and then rises to less than 10 per cent by the 1890s. Federico and Tena’s methodology thus tends to overestimate the prices of a country’s exports (and underestimate the prices of its imports) for the early nineteenth century.

There are at least two implications of this finding. Firstly, when Federico and Tena use their estimated price indices to deflate current export values, they will tend to overestimate the growth in volume, while they will underestimate the growth in import volumes. Secondly, Federico and Tena’s data should not be used to calculate the terms of trade for any country for which they have used this kind of price series.

Going forward, it does not seem fruitful to continue trying to correct prices from the core countries to estimate prices in peripheral countries because it is hard to say exactly what the other trade costs were. David Jacks has suggested they should include ‘storage costs, tariffs, taxes, and spoilage’, as well as ‘exchange rate risk, prevailing interest rates, and/or the risk aversion of agents’ (Jacks 2005, 401–2, fn. 1). As if that wasn’t complicated enough, they should also probably include the markup of the merchants doing the importing and exporting. Taking wild guesses at what these costs would have been early in the nineteenth century is unwise. Instead, prices from the peripheral countries themselves are needed, so researchers need to get to work reconstructing peripheral countries’s price histories rather than relying upon price data from the core countries.

References

Carter, S.B. et al, eds., Historical Statistics of the United States: Earliest Times to the Present: Millennial Edition, New York, 2006, Series Ee618, available online at http:/ /hsus.cambridge.org/HSUSWeb/HSUSEntryServlet (accessed 20 November 2013).

Francis, J.A. (2015) ‘The Periphery’s Terms of Trade in the Nineteenth Century: A Methodological Problem Revisited’, Historical Methods, 48:1, pp. 52-65.

Federico, G. and A. Tena-Junguito (2016) ‘World Trade, 1800-1938: A New Data-Set’, Working Papers in Economic History, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

Jacks, D. (2005) ‘Intra- and International Commodity Market Integration in the Atlantic Economy, 1800–1913’, Explorations in Economic History, 42, pp. 381–413.

Simon, M. (1960) ‘The United States Balance of Payments, 1861–1900’, in Conference on Research in Income and Wealth, Trends in the American Economy in the Nineteenth Century, Princeton, pp. 629-715.